|

I’d heard rumors about a climbing area in Central Oregon called Smith Rock, and stopped there in 1983 to see if the rumors were true. A local climber I met in the parking lot gave me a tour, which confirmed what I’d heard: that the rock was friable volcanic tuff and the area had pretty much been climbed out. But the local pointed out a new route on the Dihedrals—a blank-looking face that had been equipped with expansion bolts drilled on rappel, a new, controversial tactic. But there was a lot of unclimbed rock at Smith, the local said, so the bolt-protected routes going in weren’t going to change things all that much.

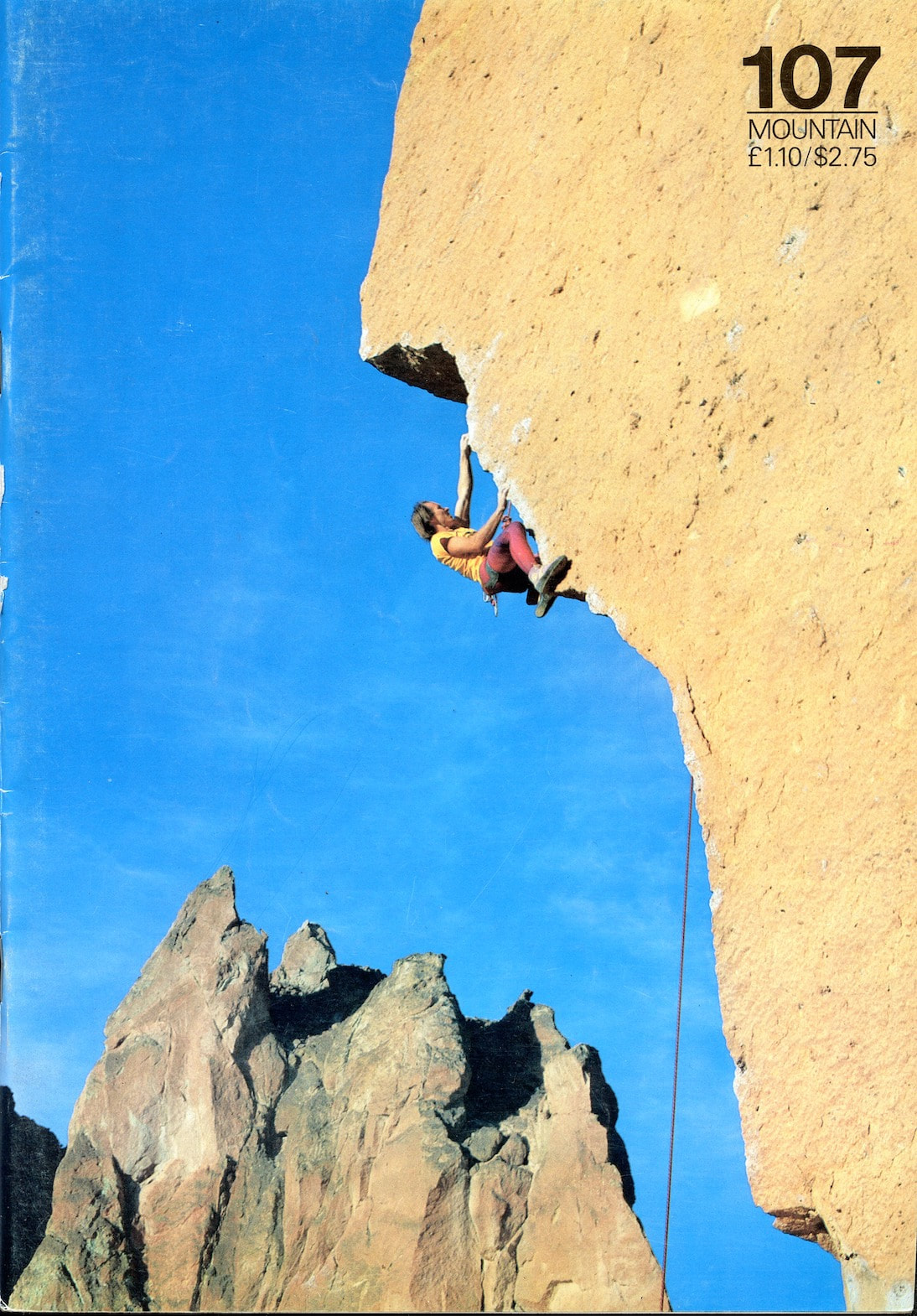

He could not have been more wrong. Within just a few years, there were dozens more bolt-protected routes—“sport climbs” in the new vernacular—mostly developed by Alan Watts with a small group of Smith Rock locals, who quietly developed some of the hardest rock climbs in the U.S. It's difficult for me to believe that my first visit to Smith Rock—and the birth of American sport climbing—happened just over 40 years ago. A lot has happened since then. Once a backwater climbing area unworthy of interest to serious climbers, in 1986, after a photo of Alan climbing Chain Reaction—considered the first sport climb in the U.S.—appeared on the cover of Mountain magazine, Smith became a destination area visited by climbers from around the world. Over the decades, more and more routes were developed, 5.12, 5.13, and eventually 5.14. Although the early focus was on establishing difficult routes, over the decades the emphasis shifted to development of countless routes at easier grades—classic single- and multi-pitch routes in the 5.7-5.10 range—that attracted more and more climbers. Saying that there are countless routes at Smith Rock is an exaggeration; Watts knows exactly how many routes there are (2271!). As the area’s guidebook author for the last 30+ years, he’s climbed nearly every route in the park and adjoining state land. His long-awaited update to the Smith Rock guide was finally published in mid-2023, just in time for the celebration of the 40th anniversary of the birth of sport climbing in America. |

Now that the guidebook is finished, Watts has been on the speaking circuit. “I’m not exactly Alex Honnold,” he says, “but I enjoy being able to share stories of the early days of sport climbing and the emergence of the climbing-gym industry.” He’s also been leading a Smith Rock climbing history tour at the annual AAC Smith Rock Craggin’ Classic in October, taking climbers young and old around the park and showing them where it all happened.

Watts doesn’t mind being called the Father of American Sport Climbing, or even the Godfather or Grandfather. Just don’t call him the Great Grandfather of American Sport Climbing. “I’m not quite old enough for that,” he says.

I had a chance to visit Smith Rock in May 2023. I didn’t get a chance to climb with Watts, but he did join me for a slideshow at Redpoint Climbers Supply located in Terrebonne, Oregon. Watts sat down with me for an interview for an article that later appeared in Bend magazine and here, for Common Climber, is the original interview.

Watts doesn’t mind being called the Father of American Sport Climbing, or even the Godfather or Grandfather. Just don’t call him the Great Grandfather of American Sport Climbing. “I’m not quite old enough for that,” he says.

I had a chance to visit Smith Rock in May 2023. I didn’t get a chance to climb with Watts, but he did join me for a slideshow at Redpoint Climbers Supply located in Terrebonne, Oregon. Watts sat down with me for an interview for an article that later appeared in Bend magazine and here, for Common Climber, is the original interview.

|

|

|

Tell me about your new guidebook to Smith Rock. How many new routes since the last edition? How many years has it been since the last edition? When did the first edition come out?

I had doubts along the way whether I had another Smith guidebook left in me, but I somehow reached the finish line. There are 2271 total routes. That’s more than a 50% increase since my last guide. There are roughly 820 new routes, though that total includes free ascents of a couple dozen old projects. My last edition came out in 2009, with my first edition released in 1992. People were always asking you “When’s the new guidebook coming out?” How long did it take from when you started to when you finished?

I think I signed a contract to do the new edition in the fall of 2017. I climbed a lot and did a few hundred of the new lines over the next few years. I compiled lists of all the new routes, and told everyone that I was working on a new guide. But I really didn’t start the grind until the beginning of 2020. I visited Smith Rock about 150 times that year, hiking everywhere, and taking more than 10,000 photos. The book gave me purpose and preserved my sanity when the world shut down. Once I had all the photos taken, I spent another year creating more than 260 photo topos and updating 50 drawings. Updating the text took another year. All told, this was a three-year project requiring about 6000 hours of work. When we go climbing at Smith, we hardly get any climbing in because everybody’s like, OMG, are you Alan Watts, will you autograph my guidebook? Do you have any funny stories about that? Or if not, how do you feel about the adoration?

|

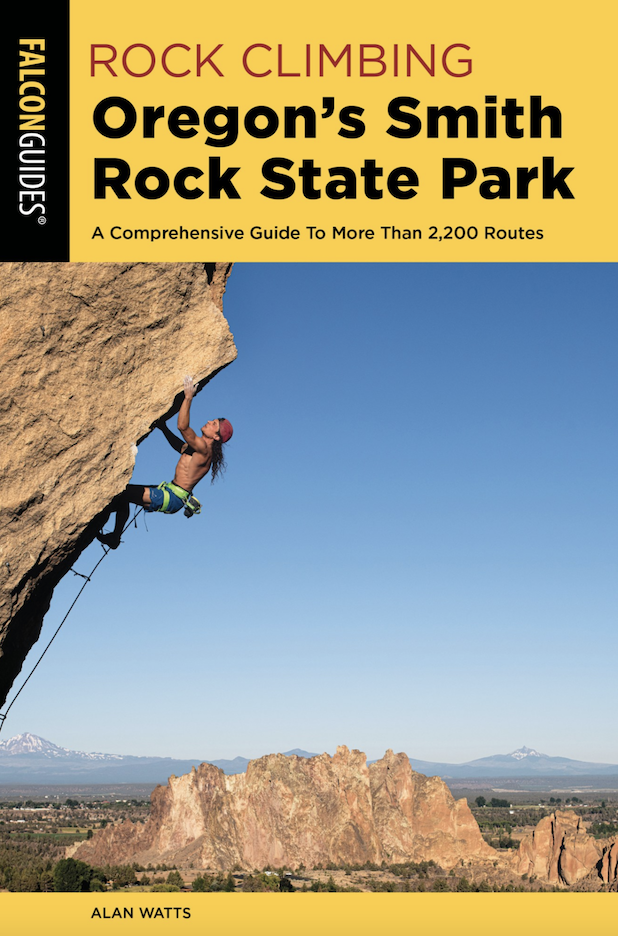

The cover of Alan Watt's updated Smith Rock guidebook (released in 2023). The book contains 2271 routes (820 are new since the last edition released in 2009) and is the most comprehensive guidebook on Smith Rock available. Alan Collins (IG: @alancollins91) graces the book's cover and in the next generation of Smith Rock climbers and leaders.

|

I’ll admit that I’ve signed a lot of guidebooks over the years. I even carry a Sharpie in my pack since I get so many requests. It’s funny how many people think that I’m the same Alan Watts who wrote books on Zen philosophy in the 1950s and 60s. After enough years of hearing the same question, I no longer remind people that the Zen Alan Watts died in 1973. Instead, I’ll say something like, “Ah yes, in each of my books lies the seeds of my next book” or some other Zen-like thing like that. And I’ll just let that float. There seriously are climbers who think we are one and the same.

I actually appreciate the attention and I never grow weary of it. I never could have imagined decades ago that climbers who weren’t even born at the time would be just as enthused about Smith climbing as I was when I was young. Everything I did in climbing during the 1980s I did for very self-centered reasons. I wanted to get good and make my mark on the climbing world. Looking back, I accomplished those two goals. But in the decades that followed, I continue to be amazed by how many people have been impacted - in a positive way - from all the work I did. I’ll never grow tired of people saying, “Thanks for all you’ve done for the sport.” I’m very grateful to have pursued something in my life that has benefited others. I doubted my alternative path from time to time, but in retrospect it was a good use of my life. I believe that I did exactly what I was meant to do in this world.

I actually appreciate the attention and I never grow weary of it. I never could have imagined decades ago that climbers who weren’t even born at the time would be just as enthused about Smith climbing as I was when I was young. Everything I did in climbing during the 1980s I did for very self-centered reasons. I wanted to get good and make my mark on the climbing world. Looking back, I accomplished those two goals. But in the decades that followed, I continue to be amazed by how many people have been impacted - in a positive way - from all the work I did. I’ll never grow tired of people saying, “Thanks for all you’ve done for the sport.” I’m very grateful to have pursued something in my life that has benefited others. I doubted my alternative path from time to time, but in retrospect it was a good use of my life. I believe that I did exactly what I was meant to do in this world.

|

People call you the Godfather of American Sport Climbing or something like that. How do you feel about that? (It’s better than Grandfather, right?)

I was there at the very start, doing the first sport routes in the first sport climbing area in the country. It’s only natural that some honorary title evolves from playing that sort of a pioneering role. In the United States I had a large impact on the emergence of sport climbing and all that followed. I had very little impact on what was going on at the same time in other parts of the world, but I consider it an honor to be included in the small group of innovators around the world that ushered in this new style of climbing. The entire climbing gym industry and climbing competitions - culminating in the inclusion of sport climbing in the Olympics - grew from the international sport climbing movement that began in the early 1980s. It would be grossly inaccurate to say that my efforts led directly to gym climbing and climbing in the Olympics. But it would be just as inaccurate to say that what happened at Smith Rock during the 1980s didn’t play a role. In the United States, the role was quite large. So, yes. I don’t mind being called the father, or godfather, or grandfather of American sport climbing. But I draw the line at being called the Great Grandfather of American Sport Climbing. I’m not quite old enough for that. When you first started developing sport routes at Smith, did you imagine the impact it would have on the park? And on the American climbing scene?

I developed sport routes at Smith Rock for a single reason. I did them because through the eyes of a climber, these routes simply had to be climbed. These are some of the most visually stunning and photographed climbing routes in the world. |

I did them for me, to satisfy my desire to do something that seemed impossible at the time. There was no pretense of trying to make an impact on the lives of future generations of climbers. But I think that history shows that innovation typically comes from obsessive individuals with a monomaniacal focus on their pursuits. That describes me during the 1980s.

|

|

The park seems a little more crowded with climbers these days than it did back in the 1980s. It’s kind of your fault. How do you feel about that?

Smith Rock is very crowded. I’ll admit that I played a role in that. I was more of a developer than a conservationist. It was my dream to someday turn Smith Rock into an international climbing destination. But when it actually happened, there was very much a feeling of “be careful what you wish for, it may come true.” The dream of receiving the attention of the climbing world was far more intoxicating than the reality. When you’re the underdog, trying to make a name for yourself, it’s a grand journey as each success takes you closer to your goal. But once you've reached the top, the dynamics change completely. There are times when I’ve felt overwhelmed by the popularity, wishing I could step back in time to the old days. But I appreciate the amazing people from all over the world I’ve met at Smith over the years. I was often lonely developing Smith during the 1980s. There were hundreds of days when I was the only climber in the park. I’m never lonely out there anymore.

Smith Rock is very crowded. I’ll admit that I played a role in that. I was more of a developer than a conservationist. It was my dream to someday turn Smith Rock into an international climbing destination. But when it actually happened, there was very much a feeling of “be careful what you wish for, it may come true.” The dream of receiving the attention of the climbing world was far more intoxicating than the reality. When you’re the underdog, trying to make a name for yourself, it’s a grand journey as each success takes you closer to your goal. But once you've reached the top, the dynamics change completely. There are times when I’ve felt overwhelmed by the popularity, wishing I could step back in time to the old days. But I appreciate the amazing people from all over the world I’ve met at Smith over the years. I was often lonely developing Smith during the 1980s. There were hundreds of days when I was the only climber in the park. I’m never lonely out there anymore.

You’ve left an enduring legacy at Smith Rock. How would you describe your legacy?

My legacy as a climber began with Smith Rock. Without question, I opened the eyes of the climbing world to this remarkable place. But my legacy as a climber extends beyond Smith Rock State Park, and that’s something I’m really proud of. The routes I did back in the 80s were groundbreaking, influential, and difficult for the era. Today, they are commonplace. But the style of climbing I developed at Smith spread like wildfire throughout the country. Every sport crag in the United States—there are at least a thousand—pays homage to what happened at Smith Rock during the 1980s.

My legacy as a climber began with Smith Rock. Without question, I opened the eyes of the climbing world to this remarkable place. But my legacy as a climber extends beyond Smith Rock State Park, and that’s something I’m really proud of. The routes I did back in the 80s were groundbreaking, influential, and difficult for the era. Today, they are commonplace. But the style of climbing I developed at Smith spread like wildfire throughout the country. Every sport crag in the United States—there are at least a thousand—pays homage to what happened at Smith Rock during the 1980s.

|

|

The new generation of Smith Rock climbers is really active in developing new routes. Who would you say is leading that effort, not just in new routes but maybe taking over your role as the driving force? If we said that the torch has been passed, who’s holding the torch right now?

Over the last decade, Alan Collins has nearly done as many first ascents at Smith as everyone else combined. Most of his routes are outside the state park boundaries, on BLM land. He has been a tremendous steward of the area, building terraces and trails at the base of the cliffs to ward off the erosion of the hillsides below. In terms of new route development, he’s holding the torch right now. Before that, young Drew Ruana pushed standards higher than ever before, doing the first ascent of Smith’s hardest route (The Assassin, 5.14d) when he was only 16 years old. But Smith Rock has never been about one person. In my generation, there were older climbers who shared their wisdom with me. This was a vital role. People like Jim Ramsey and Jeff Thomas not only inspired me but helped me define the boundary between what was and wasn’t acceptable. Now I'm one of the climbers that plays that vital role.

Over the last decade, Alan Collins has nearly done as many first ascents at Smith as everyone else combined. Most of his routes are outside the state park boundaries, on BLM land. He has been a tremendous steward of the area, building terraces and trails at the base of the cliffs to ward off the erosion of the hillsides below. In terms of new route development, he’s holding the torch right now. Before that, young Drew Ruana pushed standards higher than ever before, doing the first ascent of Smith’s hardest route (The Assassin, 5.14d) when he was only 16 years old. But Smith Rock has never been about one person. In my generation, there were older climbers who shared their wisdom with me. This was a vital role. People like Jim Ramsey and Jeff Thomas not only inspired me but helped me define the boundary between what was and wasn’t acceptable. Now I'm one of the climbers that plays that vital role.

What’s the future of Smith Rock climbing? Is it in good hands?

|

Climbing isn’t a fad and the popularity of Smith climbing isn’t going to fade away. But is the future of Smith climbing in good hands? That’s a good question. For the first time in the history of Smith Rock, climbing is no longer purely in the hands of the climbers. All new routes requiring bolts must now go through an approval process. Oregon State Parks has the final say and I fear the process could conceivably become so steeped in bureaucracy that it might mark the end of new route development. I hope I never see the day when it’s necessary to make a reservation to climb at Smith. It’ll be a tremendous challenge balancing access and the immense popularity of a place that will only grow more popular. Fortunately, the park manager at Smith Rock, Matt Davey, is very good at his job and Oregon State Parks has created a Master Plan that is excellent. There will even be a five-million-dollar welcome center built at Smith by 2025.

How about you? What’s in your future?

So far, I’ve got a whole bunch of speaking gigs lined up, sharing stories of Smith Rock climbing with the new generation, which I really enjoy. And there will be more with the book out. I’m also doing guiding and tours at Smith Rock, and we even sell some clothing my son designed. I’m starting a blog and website that are still very much a work in progress but eventually it could be a very good thing. I’m amazed how many opportunities have arisen. I’m looking forward to seeing what happens next. |

|

|