The Wimmera District in Western Victoria, Australia is largely a billiard table of wheat fields and pastures inhabited by sheep. It is unlikely territory to contain what is regarded as Australia’s premier rock-climbing area. But just outside the town of Natimuk a brown frontal of cliffs, a veritable facsimile of Uluru (Ayers Rock), rises dramatically out of the plains to attract climbers from all over Australia and many from overseas as well.

Although it is a fourteen-hour trip from my home in Sydney, New South Wales (NSW) I have lost count of the number of times that I have visited Mount Arapiles (Dyurrite) over the years. Its shimmering quartzite rock with its hidden holds, bomber slots, and smooth bulbous skin offers so many easily accessible diverse climbs of absolutely awesome quality. One climb has always stood out for many of my fellow climbers, but sadly not for me. I have lost count of the number of times I passed below and chosen not to climb it. Its easy grade and perhaps even its name, Tiptoe Ridge, made it an object of derision for me back in the day. It was only recently, when helping out at a school Outdoor Education trip, I was finally persuaded to climb it.

The instruction had finished for the day and nightfall was only an hour or two away. My old mate, Ray Lassman, then a Grampians (Gariwerd) local, had kindly travelled across to help out. We decided that we should sneak in a quick climb before the setting of the sun. Ray and I went back a long way and I was really looking forward to getting onto some rock with him again.

Although it is a fourteen-hour trip from my home in Sydney, New South Wales (NSW) I have lost count of the number of times that I have visited Mount Arapiles (Dyurrite) over the years. Its shimmering quartzite rock with its hidden holds, bomber slots, and smooth bulbous skin offers so many easily accessible diverse climbs of absolutely awesome quality. One climb has always stood out for many of my fellow climbers, but sadly not for me. I have lost count of the number of times I passed below and chosen not to climb it. Its easy grade and perhaps even its name, Tiptoe Ridge, made it an object of derision for me back in the day. It was only recently, when helping out at a school Outdoor Education trip, I was finally persuaded to climb it.

The instruction had finished for the day and nightfall was only an hour or two away. My old mate, Ray Lassman, then a Grampians (Gariwerd) local, had kindly travelled across to help out. We decided that we should sneak in a quick climb before the setting of the sun. Ray and I went back a long way and I was really looking forward to getting onto some rock with him again.

A BUNGLE IN THE “BUNGLES”

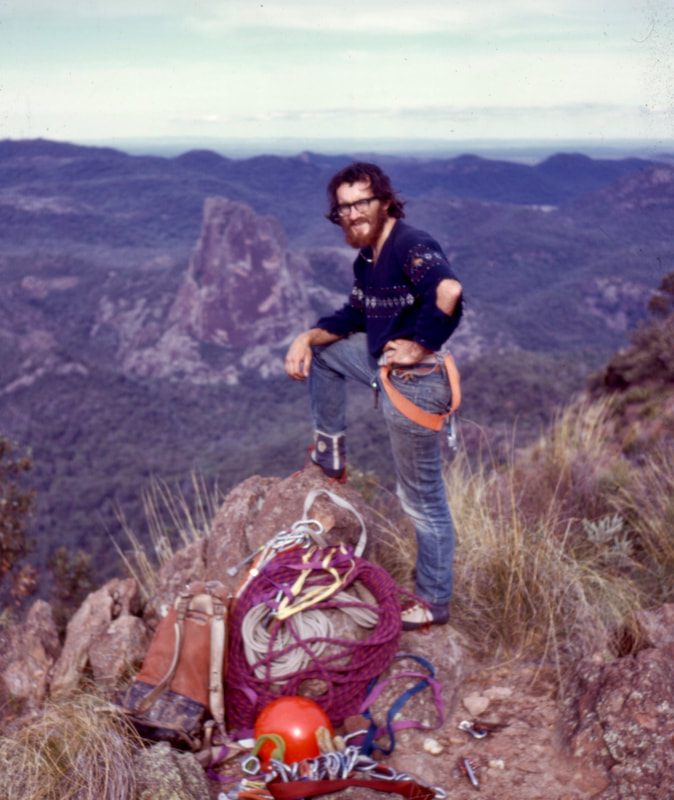

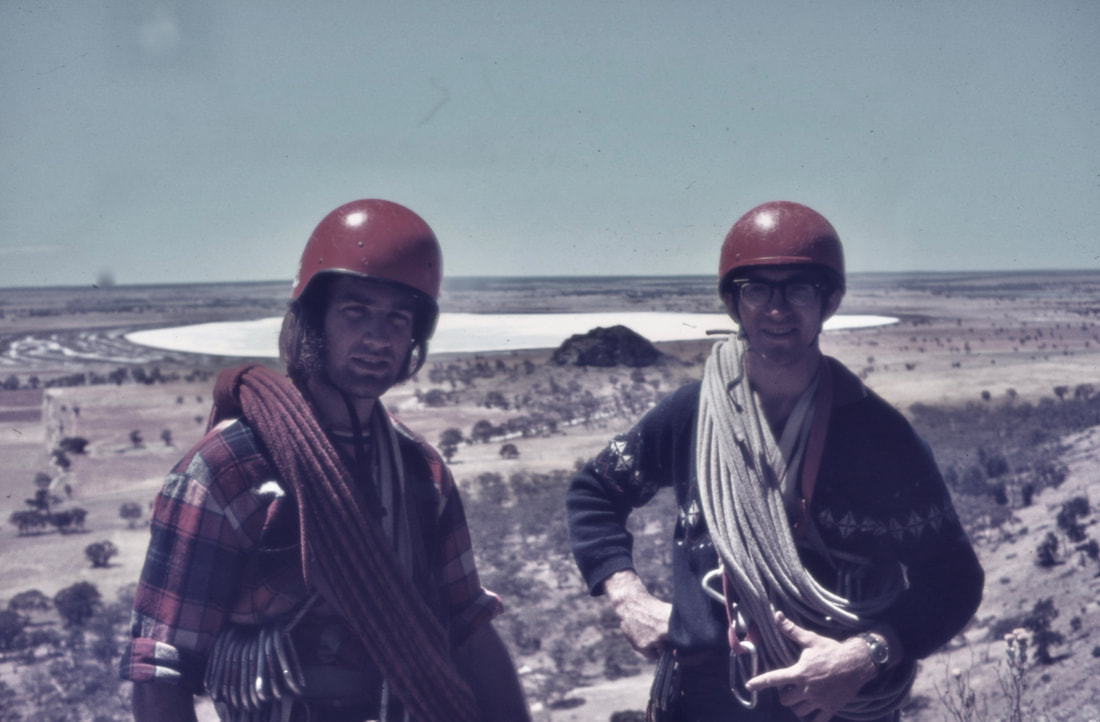

Ray and I had first climbed together as Warrumbungle neophytes in 1965. The Warrumbungle Mountains - its name derived from a word of the First Nations Gamilaroi tribe meaning “crooked mountain” - lie about 280 miles (450 kilometers) northwest of Sydney near the town of Coonabarabran. The Warrumbungles, or “Bungles,” are a spectacular collection of volcanic peaks rising abruptly out of the western plains. Though we didn’t know each other at the time, we were a disparate pair destined to become good friends and climb together throughout the years.

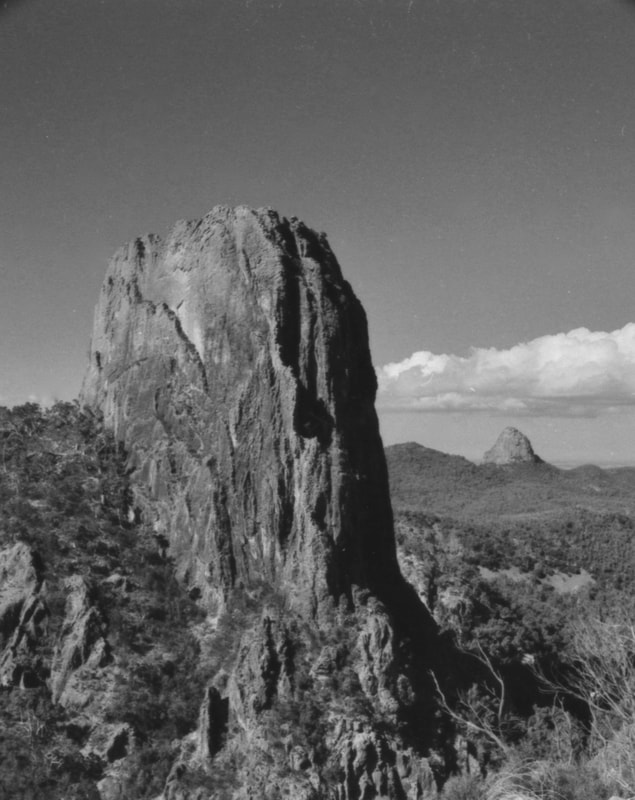

Crater Bluff with Tonduron in the background. 'Lieben' is on the other side of the peak while the 'Green Glacier' transects it from top right to bottom left behind and below the obvious shoulder. The obvious ridge on the right hand side is 'Cornerstone Rib' (14), a Warrumbungles classic. (Photo Credit: Keith Bell)

The trip to the “Bungles” was organised by Rick Jamieson, a genial giant of a man who introduced many a callow youth to the pleasures (and pains) of the outdoors. About fourteen of us were packed into a utility (small pickup), which had a makeshift galvanised iron roof covering the back tray, for the long trip to the brown, orange, red, and yellow trachyte rock that forms the main peaks - Crater Bluff, Belougery Spire, Bluff Mountain, Tonduron and the Breadknife - all remnants of free-standing solidified magma left after time immemorial had eroded their surrounding cinder cones away.

Crater Bluff was so named because, from above, its summit is U-shaped with a long central gully hollowing out its middle to drop over a cliff near its base. There are several routes up Crater Bluff. The Green Glacier or Tourist Route (Voie Normale and descent) winds its way through this lower cliff, then up the defile above. On reaching the base, Rick pointed casually and said, “You go up there.”

Unencumbered by a guidebook and gear, except for a few manilla slings and steel oval carabiners, we tied into a one-and-a-half inch (circumference) manilla rope with a bowline and half hitch and with sandshoes on our feet, we boldly went where we probably should not have ventured. Vertically challenged, we somehow managed to get up and back down injury-free (at least free from physical injuries).

|

At the time I was surprised by this success, as I had been teamed with another neophyte climber who was about half my size. The prevailing dictum at this time was that “the leader must never fall,” so it did not occur to me that my 5’6” “partner” might have been similarly alarmed when confronted by a 6’2” climber weighing in at fourteen-stone.

I had long forgotten about this, somewhat traumatic, we-got-lucky, neophytic event as for many years I thought that the first time I had climbed with Ray was in the Blue Mountains in 1969. But later, when climbing again in the “Bungles” with him, a startling discovery was made. We had decided to climb a more difficult route on Crater Bluff called Lieben (17), a route put up in 1965 by the masterful Bryden Allen, that was, for many years, considered to be the hardest climb in Australia. After climbing the route, Ray and I lounged about the summit recalling earlier memories of climbing in the “Bungles.” Ray mentioned that on his first climb there he had this terrifying experience climbing with some “big gorilla” who he thought would drag him to his death should this said primate fail to successfully swing from hold to hold. I countered by stating that on my first climb I too had a terrifying experience after being teamed up with some “midget.” We laughed at the apparent similarities (as well as the differences inherent too). During this conversation, I had been absently flicking through the summit register and came across an entry that piqued my interest. Ray Lassman Keith Bell Green Glacier Route Easter 1965 I did a double-take. Yes, I read that correctly. Though my memory had repressed it, that Easter day in 1965 was actually the first time I had climbed with Ray. We both laughed as we pieced this together and recounted our feelings of fear and trepidation that had been associated with the stature of our respective partner and our lack of climbing experience on that earlier climb. |

TIP TOEING TOGETHER

Now, many years later, my seasoned-climbing friend suggested that we ascend the long-neglected and previously forsaken Arapilean climb that I had passed so many times and chosen to ignore.

In the campsite Ray and I methodically sorted our “gear” for the “big push” up this 120 meter (nearly 400 foot) climb. Grabbing only a pair of friction boots we wandered along to its base. A quick traverse along a low but wide ledge to a frontal, then up it swinging from hold-to-hold, gaining altitude and exposure quite quickly. No ropes, no pro, no worries. I paused to look over my shoulder.

The setting sun was turning the flat countryside far below into a burnished yellow expanse and a silvery three-quarter moon had crept about 30-degrees above the horizon. Shadows had started to envelope the climb and a warm zephyr of a breeze was caressing our skin as we climbed. How good was this?

We tumbled over a lovely intervening tower into a col behind. The final wall reared above. We continued up with growing exposure to meet up with a guy and his girlfriend at the top. Swapping pleasantries as you do, we all talked ecstatically of the offerings of the route below us.

The shadows were starting to eat into the now pastel yellow field below and the moon had risen higher in the sky. It was time to head back to our campsite in “The Pines” before the curtain closed. My condescension and disdain relating to this climb had been assuaged. It was a brilliant climb.

We started out with Tiptoe Ridge, which involved great quality climbing at around Diff standard, and a short abseil off the pinnacle at the top of the second pitch. But after climbing a few brilliant routes here, we are inclined to agree with its reputation for being one of the best cliffs in the world."

-- Mike Ferguson, UK

Tiptoe Ridge (Grade 5/5.1, 380 feet - 120 metres) was climbed by Greg Lovejoy and Steve Craddock in November 1963. It was one of a trio of routes [the others being Introductory Route (Grade 5/5.1) and Siren (Grade 9/5.4)] put up in a single weekend when rock climbers first visited the cliff. All three, though easy, are out-and-out classics. What a weekend they must have had!

Tiptoe was originally climbed in five pitches and is now described in the current guidebook as:

“An alpine flavoured adventure that surely ranks as one of the finest routes of its grade in the world – an absolute must-do for every visitor to Arapiles – Dyurrite.”

This is an assessment that I have come to wholeheartedly agree with and have climbed it many times since. So why did it take so long for me to climb Tiptoe Ridge?

My first climbing trip to the area was in December 1971 with Dave “Nippa” Shirra and Ray. On subsequent trips I quite often joked with fellow climbers about their climbing ability by comparing it to the “low-grade” standard of Tiptoe Ridge. The reasons why this climb was selected for these jokes is not clear, as I have climbed Introductory Route, Siren, and many other easy classics, sometimes on many occasions. But as mentioned, its embryonic beginnings combined with its name, relegated Tiptoe Ridge to kindergarten status. So, for many years it did not appear on my climbing radar.

Although I certainly missed out on a good thing back in the day, in retrospect, my avoidance of this climb ultimately allowed me to go on a voyage of discovery on a stunning and picturesque climb with a really good friend.

After the climb I felt as though I had delved into a previously neglected and overlooked crevice and found gold. Although grunting up harder grades certainly has its own rewards, I believe we grow as climbers when we embrace the full spectrum of grades and techniques that climbing has to offer This includes romping up an easier out-and-out classic - particularly with an old friend. Fun, companionship, moving smoothly over rock; isn’t that really what climbing is all about?

TIPTOE RIDGE (380’):- The climb follows the arete of the pinnacle buttress to the pinnacle and then ascend the wall at the rear to the top.

Grade:- Very Difficult

First Pitch 140’:- The climb begins on the same terrace as the slot. Traverse on to the face of the ridge, then straight up, and belay where convenient.

Second Pitch 100’:- Continue up the ridge on large holds and belay on a broad ledge, to the left of, and 40’ below the summit of the pinnacle.

Third Pitch 40’:- Move up the pinnacle to the top. The last few feet are interesting. An interesting alternative is to ascend the pinnacle up the southern side, traversing on to the normal route when about 15’ from the top.

Fourth Pitch 130’:- Climb down the back of the pinnacle to the ledge. Move left across the face for 20’ and then back right to numerous belays on the edge of the gully adjacent to the introductory route cave.

Fifth Pitch 70’:- Move easily to the top.

First Climbed:- Greg Lovejoy, Steve Craddock – Alternate leads (16/11/63).

* Dyurrite and Gariwerd are the First Nations names for Mount Arapiles and the nearby Grampian Mountains respectively.

Author's Notes:

- My thanks to Glenn Tempest for kindly allowing the use of his photograph and supplying the description of the route in the 1965 guidebook.

- My thanks also to Maria Dixon and Mike Ferguson for allowing me to use text and photographs from their article, "Down Under" in the York Mountaineering Journal, UK.