As climbers we often trek through fields, woods, forests, snow, swamps, sometimes even deserts to reach the rocky ramparts that we climb. Whether the approach is short or long, we hang in there with grim determination usually with a heavy pack to reach the base of our rocky reveries. After attaining the pinnacle of our dreams, we are then faced with the return to our camp or back to civilisation. Sometimes, in achieving this, we meet the furry, feathered, and scaley denizens of these areas, at times to our wonderment and amazement, at other times to our dismay. Over a long career, I have memories of such encounters particularly of the feathered kind. This is the first part of two articles written about "Animal Acts" experienced while climbing.

Pauligk’s Parrots

There is an Australian climber who had a penchant for winged things, namely in the shape of a menagerie of parrots. An immigrant from East Germany, this climber is also renowned for revolutionising previously unprotected wall climbing in the mid 1970’s. By utilising his Germanic thoroughness, Roland Pauligk invented and manufactured the impeccable, useful, and legendary RP nut. Roland had already attained legendary status with his bold first ascent of Electra at Mt Arapiles; a powerful and talented climber, he was built like the proverbial "brick outhouse." It was in the late 1960’s when I first crossed paths with Roland, his partner Anne, and Keith Lockwood, all Arapilean stalwarts from south of the border (Victoria, Australia) at the Warrumbungle Mountains (1) in NSW (New South Wales, Australia).

[Click to enlarge the above photos; Hover or click to see caption]

|

My climbing partner, Howard Bevan and I had just completed an ascent of Out and Beyond on Belougerys Spire. (Out and Beyond is a climb in the Warrumbungles whose name was derived from a long traverse on its second pitch beginning with 30 feet of exposure but ending 120 feet later with your backside hanging over a 300 drop - another Bryden Allen "Bungles" classic.) On arrival back at our camp in the nearby Balor Hut we met up with Roland, Anne, and Keith, as well as Roland’s and Anne’s three parrots. While sitting and chatting around a campfire that night, Howard and I informed the threesome that we were going to have a go at Lieben on Crater Bluff the next day (for many years this had been regarded as the hardest multipitch climb in Australia.)

Ours was the fourth ascent of Lieben and Roland, Anne, and Keith, as well as their "feathered friends," decided to come along and watch from a vantage point near the bottom. Now one of their flock, wanting to get a closer look at the action, flew up and perched on an important handhold just above me on the crux pitch. I was in a steep, relatively unprotected section with ropes hanging down loosely to my belayer. Each time I reached out to use the handhold, which also apparently doubled as a nice perch, a slashing curved beak would nip at my hand. As I hung about trying to get past this troublesome bird, some crazy thoughts went through my mind. |

“Polly, want a cracker?” -- My pro largely consisted of Ewbank "Crackers" and a swipe with what John called his "Kiss of Death", a large solid 4-1/2 inch-long hexagonal aluminium nut would surely remove the problem.

|

On second thought, a bit extreme perhaps? My peg hammer maybe?

What if I used it to gently push the parrot off its perch to open the gate so I could progress? But ill-conceived thoughts of the parrot falling to its death at Roland’s feet some 150-metres below jangled in my addled mind. Tangling with Roland made me think I would be better off going tandem with the bird. In the end, though, it was going to be the cocky or me and stuff the consequences. I took out my peg hammer, reached up and gently but firmly pushed the bird off its perch. It fell completing a neat somersault before it unfurled its wings and thankfully flew away without sustaining any damage. The next day Roland and Keith Lockwood did the fifth ascent, and I was pleased to see the parrot sat on the former’s shoulder as he climbed the crux pitch. At least he had a feathered handicap too. |

Flight of the Phoenix

Back in the day I was reading the latest Ascent magazine in the book section of Steve Komito’s shop at Estes Park in Colorado when something caught my interest. Customers came and went but I didn’t notice them. My concentration was fixed on a photograph, a shot of a climber on Bluff Mountain, a peak in the Warrumbungle National Park back home in Australia. I didn’t really notice the climber as I was mesmerized by an architecturally beautiful, seductively attractive section of rock to his right. I felt sure that a route could be made to go on that rock and carried the dream halfway across America, then, over the Easter of 1974, the opportunity presented itself and the challenge was taken up.

My old mate, Ray Lassman and I tiptoed up the scree at the base of Bluff Mountain – the pre-eminent peak of the "Bungles," The intervening years had seen us both progress beyond our former beginner status to take on this first ascent. After two hard pitches up the initial pedestal, two things made us think of backing off. One was the vertical sweep of rock out right that we would need to first descend to and then climb; the other was the freezing early morning winds that were blowing and buffeting around us. Bryden Allen’s words in the “Bungles” section of his seminal 1963 NSW guidebook came to mind.

“One is likely to freeze in a biting wind in the early morning and suffer from heat exhaustion in mid-afternoon.”

Despite the conditions, Ray and I decided to push on, doing a short abseil down to a small stance capped by a long overhanging lip of rock heading out right seemingly almost to South Australia. “Watch me!” I said as I launched out onto the wall below it. Slick yellow rock presented itself and steep at that. My arms took a pounding, but the protection slotted in easily. The yellow rock gave way to rough reddish brown and the angle eased. Beautiful gymnastic moves came to hand. I moved on up. Incredible. An unusual hole above a ledge took a bomber number 10 hex. “On belay," I called for Ray to climb. The wind dropped and the warmth of the sun now etched and caressed our skin. We were in for a fine day.

My old mate, Ray Lassman and I tiptoed up the scree at the base of Bluff Mountain – the pre-eminent peak of the "Bungles," The intervening years had seen us both progress beyond our former beginner status to take on this first ascent. After two hard pitches up the initial pedestal, two things made us think of backing off. One was the vertical sweep of rock out right that we would need to first descend to and then climb; the other was the freezing early morning winds that were blowing and buffeting around us. Bryden Allen’s words in the “Bungles” section of his seminal 1963 NSW guidebook came to mind.

“One is likely to freeze in a biting wind in the early morning and suffer from heat exhaustion in mid-afternoon.”

Despite the conditions, Ray and I decided to push on, doing a short abseil down to a small stance capped by a long overhanging lip of rock heading out right seemingly almost to South Australia. “Watch me!” I said as I launched out onto the wall below it. Slick yellow rock presented itself and steep at that. My arms took a pounding, but the protection slotted in easily. The yellow rock gave way to rough reddish brown and the angle eased. Beautiful gymnastic moves came to hand. I moved on up. Incredible. An unusual hole above a ledge took a bomber number 10 hex. “On belay," I called for Ray to climb. The wind dropped and the warmth of the sun now etched and caressed our skin. We were in for a fine day.

The two of us stood on the ledge. Above, the overhang brooded in silent shadows while the rock around us was a sea of shimmering crystals. I led out to find that the shimmering crystals coalesced into jugs; I was bewildered by the array of holds on the wall. Random thoughts flashed through my mind - the volcanic conception of its birth, convulsed by heat and pressure, then slowly cooled, left large hexagonal prisms; solid rock and good nut placements were its climbing legacy. I ascended hoping the pitch would not finish. A perfect pitch, a magnificent position, and alas, too short, as a small ledge stepped across my vision. Ray was ecstatic at the experience when he joined me on the ledge.

Twelve metres above, the diagonal overhang reached its zenith as it swooped rightward across the face in its dying movement. An impasse? Only one way to find out. Amazingly, this section still sported the same holds, protection, and incredible position. I reached the roof near the transition, moved right and belayed in a small niche below the overhang. As I waited for Ray, I reflected on the three pitches below; they must surely rate as the best sequence of pitches I have climbed in Australia. Poetry on rock.

Above me was steep, seemingly blank rock melting into a sea of azure blue sky. But more delightful wall climbing continued for a number of pitches ultimately leading into an overhanging amphitheatre of rock. The wind had abated by now and the sunshine streamed down, striking up the orchestra of heat and rapidly becoming oppressive.

Twelve metres above, the diagonal overhang reached its zenith as it swooped rightward across the face in its dying movement. An impasse? Only one way to find out. Amazingly, this section still sported the same holds, protection, and incredible position. I reached the roof near the transition, moved right and belayed in a small niche below the overhang. As I waited for Ray, I reflected on the three pitches below; they must surely rate as the best sequence of pitches I have climbed in Australia. Poetry on rock.

Above me was steep, seemingly blank rock melting into a sea of azure blue sky. But more delightful wall climbing continued for a number of pitches ultimately leading into an overhanging amphitheatre of rock. The wind had abated by now and the sunshine streamed down, striking up the orchestra of heat and rapidly becoming oppressive.

[Click to enlarge the above photos; Hover or click to see caption]

|

We were hot and thirsty, but elated at our progress. I was leading one of the higher pitches when suddenly the rock around me fell into a deep shadow. I looked over my shoulder to see a band of golden neck feathers only ten feet behind me that gleamed in the sun. A huge wedgetail eagle, with a wingspan of around 2.5 m (9 feet) and a body length of just over a 1 m (3 feet), was the source of the shadow as it soared gracefully on the thermal created by the steep rock face. The massive bird remained stationary, with its outspread wings and outer pinions tickling the air. Its intense, keen eyes were set above a large, hooked beak - it was sizing me up. With the hot breeze, the warmth of the rock combined with the backlit glow of golden feathers, it seemed like the Phoenix was arising from the ashes - a winged messenger of renewal and resurrection?

The heat, the sun, the rising eagle, our renewed enthusiasm, and the long rightward traverse all merged in my mind. We had safely ascended and descended, and the experience of it reminded me of the freedom gained in an old movie that I had seen some years earlier, where a crashed aircraft in the desert was resurrected in a different form thus enabling its stranded survivors to fly to safety. And so, arose The Flight of the Phoenix, Warrumbungles style; others were later to name the long rightward overhanging lip, "the eagles wing." |

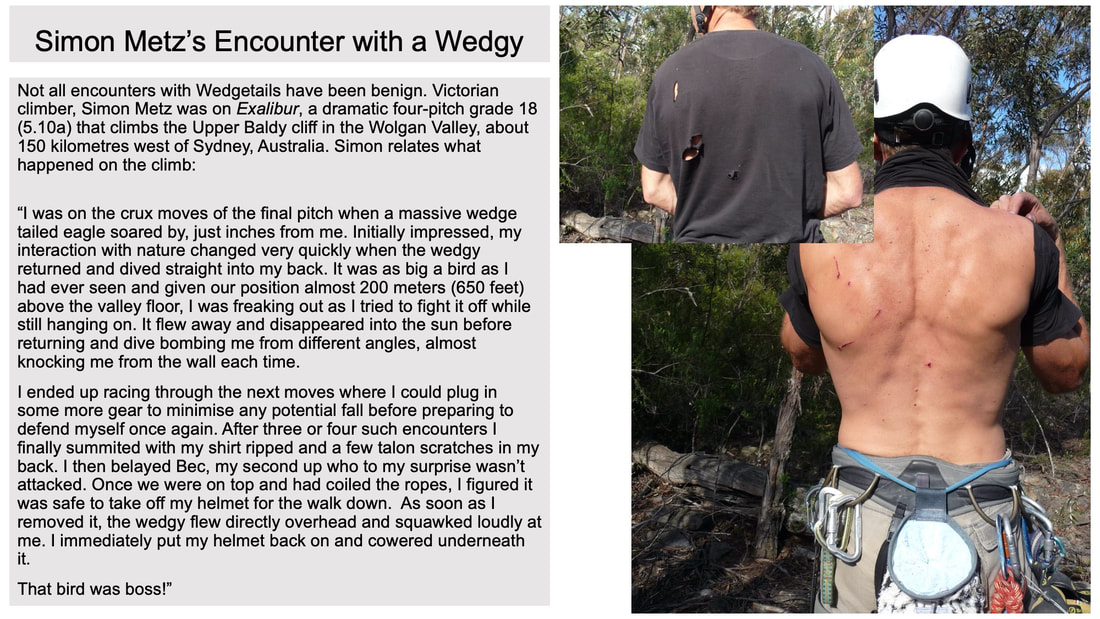

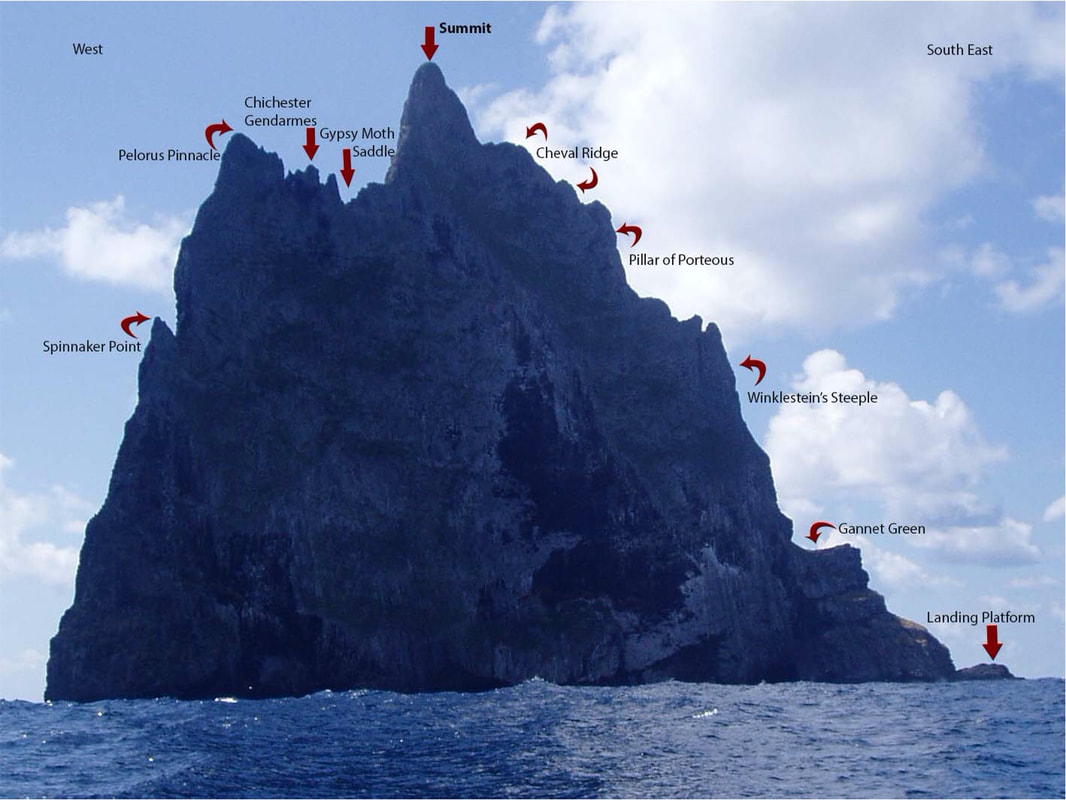

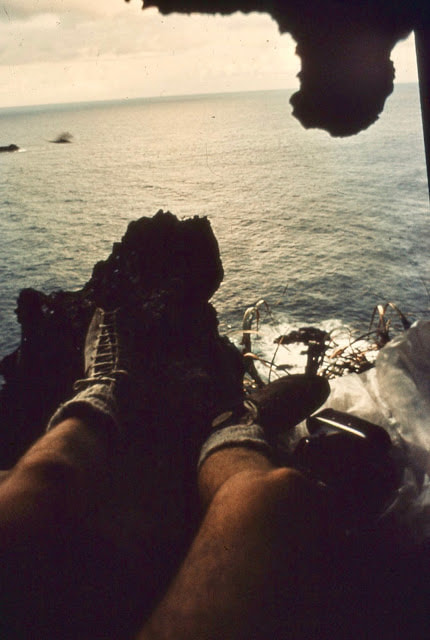

Balls Pyramid

Balls Pyramid, is a mediaeval citadel puncturing the Tasman Sea, some 700 kilometers north east of Sydney and about 20 kilometers from the nearby Lord Howe Island. Climbing and all recreational access to Balls Pyramid has been banned since 1986, in order to preserve the last home of a mysterious inhabitant – the rarest insect in the world but more about it later.

The air around the Pyramid is in constant motion as birds of varying types wheel, soar, or dive, displaying amazing aerobatic manoeuvres and stunts. Members of the French Expedition in October 1984 were so disturbed by the number of screeching, wheeling seabirds that they likened the Pyramid to a set from Alfred Hitchcock’s film, The Birds.

“The first night was hellish, the sea thundered continually and the birds that we disturbed came and sat on our beds with piercing screeches. We were in a full-on Hitchcockian environment!” (French Team)

Indeed, it is difficult to take a photo without at least one bird or more appearing in it.

The air around the Pyramid is in constant motion as birds of varying types wheel, soar, or dive, displaying amazing aerobatic manoeuvres and stunts. Members of the French Expedition in October 1984 were so disturbed by the number of screeching, wheeling seabirds that they likened the Pyramid to a set from Alfred Hitchcock’s film, The Birds.

“The first night was hellish, the sea thundered continually and the birds that we disturbed came and sat on our beds with piercing screeches. We were in a full-on Hitchcockian environment!” (French Team)

Indeed, it is difficult to take a photo without at least one bird or more appearing in it.

[Click to enlarge the above photos; Hover or click to see caption]

|

Most of the climbing on the Pyramid was on its ridges, but often when obstacles were encountered a deviation was required onto its side walls. On the Southern wall on the inside of the caldera there was a manoeuvre sure to increase the heartbeat by leaning out on your arms and looking down through your legs at the surf breaking hundreds of metres below on the base of the rock. In 1970, on the first ascent of the West Ridge, I was high on the steep Southern face when a beautiful little lone Noddy Tern landed on a ledge beside my left elbow. These were pert little birds with blackish grey bodies, a touch of white on head and tail, all surmounted by a thin sharp black beak. I was intrigued by the bird's lack of fear and brazenness. As I watched with curiosity, then amazement, it suddenly regurgitated a relatively large freshly caught fish. A gift from the heavens without the accompanying loaves?

Surrounded by ocean, the birds fished during the day and returned at sunset to their usual roosting places. On the West Ridge we faced the setting sun and were often confronted with the silhouette of a Mutton Bird with its wings outstretched and webbed feet facing forward as they put on their air brakes, stalled and then fell awkwardly onto the ledge. Throughout the stall these good-sized birds were totally out of control and many of them crashed into us. This was OK at sunset, while we were awake, but during the night sometimes these awkward flying missiles crashed into us as we were trying to sleep. We would also often wake up with a bird or two roosting on us or tucked into our side for warmth. Mostly we just moved them onto the ledge beside us as they were quite friendly and unafraid. During the day a helmet was mandatory not only for loose falling rocks but also for the fishy smelling guano that rained down from on high. |

[Click to enlarge the above photos; Hover or click to see caption]

The crash landings of the birds created a hilarious scene on the last night of our trip. We had split into two groups to cook the last dinner, one in the small and cramped base camp cave and the others on the narrow ledges about twenty feet below. The two people above were waiting for their billy (2) to boil when a Mutton Bird dropped in for the night. It alighted on the edge of the billy singeing its tail in the near boiling water then squawked, flapped and upset the billy off the burner. The top group desperately tried to save the stove, the billy, and the bird but only managed to salvage the former. The billy and its steaming contents plummeted towards the four climbers on the narrow ledge below. They scattered as best they could to avoid either being clonked, scalded or dropped over the edge. The melee finished with the pervading smell of burning feathers and a rather distressed Mutton Bird flying off into the sunset. Everybody fell about laughing (nervously) given the slapstick element of the situation, but then concern emerged for the bird as well as for one of our number who had lost the only billy that he had ever owned.

In 1973, I returned with Greg Mortimer to attempt the first skyline traverse and alpine style ascent of the Pyramid starting on its South East end, climbing it to the summit, then descending the West Ridge.

On the first ascent of the West Ridge in 1970, we reached a section called the Chichester Gendarmes (3), a line of decaying towers, the foundations of which were undermined by holes or windows eroded by wind right through the Pyramid. To avoid this section, we had abseiled down the Northern wall onto a convenient ledge that allowed us to bypass the tottering towers. A fixed rope was left up this steep wall to regain the ridge. I regarded that climbing this previously abseiled section would determine the outcome of the traverse as it remained an unknown quality. Was it climbable?

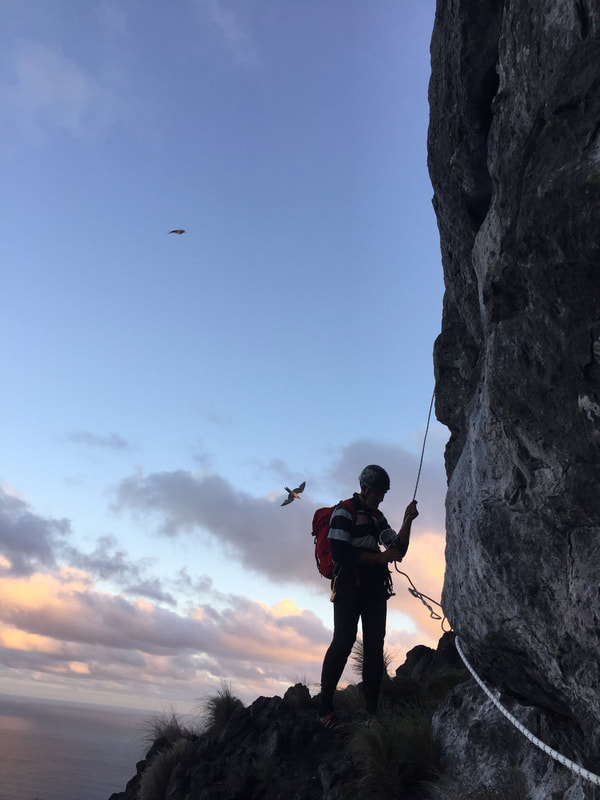

On our second night Greg and I had reached the summit and descended to a large open cathedral like cave near the bottom of the summit needle. On the summit the weather had been cloudy and windy but overnight it had deteriorated markedly. By the time that we reached the base of the abseil the weather had deteriorated further as the harbinger of an approaching cyclone (hurricane) was making its ominous presence felt. Rain, swirling wind and a crashing ocean almost 500 metres below would be ever-present companions on my attempt to climb the pitch. Little did I know that there would be other surprises in store for me?

All went well until at about the 80-foot mark I came across a sentry box that was difficult to see from below. As I began to move up past the base of it a red-tailed tropic bird (4) flew out of it into my chest, brushing past me in a flurry of wings and webbed feet frightening the crap out of me. I had hardly recovered from this scare when memories of Lieben came flooding back as its chick rushed across, then pecked my hand as I used the juggy edge of the sentry box for a handhold. This time, of course, I didn't toss the bird off.

Allowing my heart rate to settle I was able to continue on to attain the ridge. The key turned and we were able to complete the descent to the 1970 base camp cave to be confronted with one of the most ferocious nights that I have ever spent - anywhere. With barely enough room for the two of us with our packs, nylon bivvy sheets and nothing to tie to, we sat back to experience the full fury of Cyclone Kirsty which hit later that night.

“It was a maelstrom, an amazing release of natural forces – a great vortex of wind, water and birds, like a column hanging in the air in front of us and seeming to blast right over the top of the Pyramid. It was frightening!’ (Greg Mortimer)

In 1973, I returned with Greg Mortimer to attempt the first skyline traverse and alpine style ascent of the Pyramid starting on its South East end, climbing it to the summit, then descending the West Ridge.

On the first ascent of the West Ridge in 1970, we reached a section called the Chichester Gendarmes (3), a line of decaying towers, the foundations of which were undermined by holes or windows eroded by wind right through the Pyramid. To avoid this section, we had abseiled down the Northern wall onto a convenient ledge that allowed us to bypass the tottering towers. A fixed rope was left up this steep wall to regain the ridge. I regarded that climbing this previously abseiled section would determine the outcome of the traverse as it remained an unknown quality. Was it climbable?

On our second night Greg and I had reached the summit and descended to a large open cathedral like cave near the bottom of the summit needle. On the summit the weather had been cloudy and windy but overnight it had deteriorated markedly. By the time that we reached the base of the abseil the weather had deteriorated further as the harbinger of an approaching cyclone (hurricane) was making its ominous presence felt. Rain, swirling wind and a crashing ocean almost 500 metres below would be ever-present companions on my attempt to climb the pitch. Little did I know that there would be other surprises in store for me?

All went well until at about the 80-foot mark I came across a sentry box that was difficult to see from below. As I began to move up past the base of it a red-tailed tropic bird (4) flew out of it into my chest, brushing past me in a flurry of wings and webbed feet frightening the crap out of me. I had hardly recovered from this scare when memories of Lieben came flooding back as its chick rushed across, then pecked my hand as I used the juggy edge of the sentry box for a handhold. This time, of course, I didn't toss the bird off.

Allowing my heart rate to settle I was able to continue on to attain the ridge. The key turned and we were able to complete the descent to the 1970 base camp cave to be confronted with one of the most ferocious nights that I have ever spent - anywhere. With barely enough room for the two of us with our packs, nylon bivvy sheets and nothing to tie to, we sat back to experience the full fury of Cyclone Kirsty which hit later that night.

“It was a maelstrom, an amazing release of natural forces – a great vortex of wind, water and birds, like a column hanging in the air in front of us and seeming to blast right over the top of the Pyramid. It was frightening!’ (Greg Mortimer)

|

Settling into the cave, an oppressive gloom descended over the surrounding ocean. It was a turbulent, seething mass, waves were crashing in from all directions, froth, foam and spume made a white apron that encircled the Pyramid for about 500 metres from its rocky shore. Right before our eyes birds were ripped from the Pyramid, their wings useless, and twisted appendages of their bodies to be dashed into the gyrating, surging mass below. Numerous dark carcases could be seen floating amid the white and turbulent surface. The wafer or aerodynamic shape of the Pyramid also divided the wind into two differential air streams. These collided violently causing massive vortexes to go zooming up the face just in front of our refuge. Everything intensified during the night, but it was largely hidden by the darkness and the 300 millimetre thick waterfall that was streaming over the mouth of the cave.

At dawn we resumed our grandstand view of the awesome power and destruction of the cyclone. Birds, rocks, plants continued to be torn from the heights. By 10:30 it was almost over as blue breaks began to appear. By noon the Pyramid was surrounded by a clear blue sky, but massive waves continued to buffet its base. About three days later a fishing boat from the nearby Lord Howe Island appeared as our food and water were running out. We had to swim for it. We perched on rocks as close as we could get, judging the break of the 5 metre waves breaking about 20 metres out. We leapt in and swam the 50 metres through the rocky shoals to the boat. Tired and battered when we reached the boat, we just stretched out our arms and the Islander fishermen snatched us out of the water onto the boat; fortunately, they did not use a gaff. |

[Click to enlarge the above photos; Hover or click to see caption]

Mothballed

|

These wings belong to a peculiarly Australian phenomenon – the Bogong Moth. The moth’s name is derived from the Aboriginal Dhudhuroa word, bugung, a description derived from its plain, brown colouration. These moths are fairly large and have a wingspan between 40 – 50 millimeters (1.6 – 2.0 inches), and a body length of around 25 – 35 millimeters (1 – 1.4 inches.) They were an important food source for First Nation Peoples as well as for many native animals. The Bogong Moths are night flying aeronauts that migrate in great numbers in the spring, resting in cracks and crevices during the day.

In 1968 Howard Bevan and I decided to have a crack at the John Ewbank, Mt Piddington (Wirindi) classic - Genesis (16). Howard hopped on the line, working his way up and then, in his words: “I placed my forearm into the crack in order to set the jam. Instead of solid rock, it was squishy and vaguely wet. My comment of surprise to Keith was enough to set in motion a veritable avalanche of moths out of the crack above onto my head and down into my shirt. There was a cavalcade of millions of the buggers, all I could do was put my chin on my chest and struggle to breathe.” |

|

While Howard struggled to breathe, I was struggling to stop laughing as he was engulfed by the avalanche of millions of moths that had been residing in the full 30 metres of the climb's widish-crack. Such was the flood of moths that it seemed the crack had been cleared of its ‘things with wings’. Howard continued his ascent.

While I was pleased that he had largely cleaned it, I was still confronted by the occasional squishy moth - or slimy moth remnants from Howard's ascent as I seconded the climb. In the intervening years these infestations have occurred to a much lesser degree, a symptom perhaps of the decreasing numbers of insects occasioned by the effects of climate change. Given the environments that we climb in I’m sure every climber has a bird story whether it is observational or an engagement that they have experienced. In Australia we count our blessings that Emus can’t fly, and Cassowaries (5) can’t either. Next time: The things that slither slide or walk on "Terra Firma." |

The author would like to specially thank the Australian Museum for the use of photos taken during the AM Balls Pyramid Scientific Expedition in 2017.

A special thanks should also be given to Ian Hutton, Curator of the LHI Museum for freely allowing me to use his amazing photos of Balls Pyramid

and its birdlife. Ian was an supporter, organiser and valued member of the AM Expedition.

A special thanks should also be given to Ian Hutton, Curator of the LHI Museum for freely allowing me to use his amazing photos of Balls Pyramid

and its birdlife. Ian was an supporter, organiser and valued member of the AM Expedition.

- The Warrumbungle Mountains - its name derived from a word of the First Nations Gamilaroi tribe meaning “crooked mountain” - lie about 280 miles (450 kilometers) northwest of Sydney near the town of Coonabarabran.

- A billy is a cylindrical can of varying sizes made of aluminium or steel with a closed and open end. A wire handle is fitted to the open end and it is used to boil water or cook food usually on campfires in Australia.

- Named after Sir Francis Chichester, a British aviator who made the first east-west flight between New Zealand and Australia in 1931. Chichester flew his Gypsy Moth aircraft past Balls Pyramid and noted windows (holes) in it below the series of towers that bear his name.

- The red-tailed tropicbird measures 95 to 104 cm (37 to 41 in) on average, which includes the 35 cm (14 in) thin red tail streamer and weighs around 800 g (30 oz). It has a wingspan of 111 to 119 cm (44 to 47 in) and has a streamlined but solid build with almost all-white plumage, often with a pink tinge.

- The emu is the second largest living bird reaching a height of 1.9 metres (6’2”). The Cassowary is the third tallest and second heaviest bird, its strong legs can inflict serious or fatal injuries, giving it the reputation of being sometimes labelled ‘the world’s most dangerous bird’.