Since many of our climbs occur out in the wild it increases the prospect of a chance encounter with some of the wildlife that inhabits our chosen climb and its surrounding countryside. As much as these animal encounters add intrigue and awe to our adventures, they also add spice and perhaps induce a bit more adrenaline into the system.

In Australia we have a bevy of reptiles, spiders, insects, sharks, and even some four-footed animals, ready to put the bite on - or at least scare - the unsuspecting climber. Some of our "wild things" in Australia are among the most poisonous in the world. But America also has its fair share of poisonous, slithering and crawling creatures, some with pretty big jaws fitted with big teeth, so I will begin stateside.

In Australia we have a bevy of reptiles, spiders, insects, sharks, and even some four-footed animals, ready to put the bite on - or at least scare - the unsuspecting climber. Some of our "wild things" in Australia are among the most poisonous in the world. But America also has its fair share of poisonous, slithering and crawling creatures, some with pretty big jaws fitted with big teeth, so I will begin stateside.

A Snakey Whipper

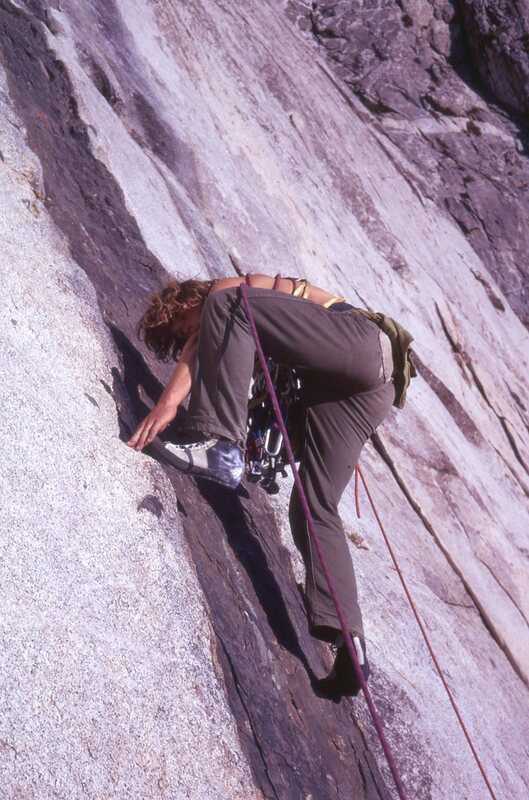

I arrived in Yosemite in the middle of 1973 and teamed up with Alan Dewison, a British climber I had met in Chamonix a year or two earlier. Among some of the climbs that we did was the classic long corner, The Braille Book (5.8/16) on Higher Cathedral.

On this day, I was merrily leading up the final corner of The Braille Book and decided to look for a bit of pro. Out right, there was a small rising diagonal crack in the wall that looked like that it might take something. It did. Ensconced in the crack was what we in Australia call a "Joe Blake," our slang for a snake. There was a resplendent length of yellow, red, and black bands snaking along the inside of the crack.

On this day, I was merrily leading up the final corner of The Braille Book and decided to look for a bit of pro. Out right, there was a small rising diagonal crack in the wall that looked like that it might take something. It did. Ensconced in the crack was what we in Australia call a "Joe Blake," our slang for a snake. There was a resplendent length of yellow, red, and black bands snaking along the inside of the crack.

|

Now this snake was a kingsnake - harmless - but it looks a lot like the highly venomous coral snake, which has a neurotoxin that can easily kill a human. (Coral snakes are actually shy with very small mouths that you'd practically have to force your little-finger into it to get bitten. But an American rhyme to tell the difference between a coral snake and a non-venomous kingsnake is "red on yellow, kill a fellow...red on black, venom lack.") Its bright colours, however, are a good warning for the uninitiated to keep away.

Seeing a serpent still takes me aback, making me wary, but it is an amazing sight, nonetheless. While this brightly coloured snake was clearly visible, it had also tightly wedged its full length into the crack, thereby largely immobile. Hmmm, no pro to be got there. I then placed the protection into the main crack and continued to the top of the climb. I found a belay with a good line of sight down the corner. It was now Alan's turn. Over the years, with many interactions with Brits in Australia, I had casually observed that they have a real fear of snakes, sharks, scorpions, lizards, and many other types of our strange fauna. I laughed to myself and wondered whether I should point the snake out to Alan? As Alan started to happily ascend the corner, my mischievous side got the better of me and I cheekily said that he should take a peek at that particular piece of crack. Alan peered into the crack, followed by an incredibly loud scream that reverberated up the valley as he simultaneously completed a spectacular thirty-foot pendulum out of the steep corner. It was brilliant. Arriving shakily at my belay - ashen faced and silent - I could tell he was a bit "snakey" with me. As we furled the double ropes, I thought he might strategically snake a few coils around my neck, but by the time we got back to the valley floor, all was almost forgiven. |

|

A Bit Rattled

In the 1970’s Yvonne Chouinard at the Great Pacific Ironworks in Ventura California kindly provided a welcome oasis in the basement for international climbers to rest and recuperate while transiting to or from Yosemite. It was here I teamed up with Doug Robinson and we beetled around the Sierra Nevadas in his VW Kombi for many weeks, hitting some more great routes together. One day when he could not climb, he suggested that I should do the second ascent of Smokestack, a route that he and Galen Rowell had put up a couple of years earlier on the Rabbits Ears of the Wheeler Crest.

A mate of Doug’s, Jay Jensen was able to climb with me and we had a great day on this 1,000-foot buttress. While up there it was hard not to notice Adams Rib the adjacent buttress, again put up by Doug and Galen with Chuck Kroger. Jay wasn’t able to make it, but Vern Clevenger was keen to make the ascent.

Vern and I were hauling arse up the approach gully when, at the halfway point, I reached a long table of rock straddling the gully with a dark void underneath. As I put my hand on the top to pull up onto it there was an ominous rattling from the blackness below. I peered into the darkness and there, a triangular head or two with a few coils, were shaking their rattles to inform me of their presence. I quickly headed to the right side of the table, thinking it was very obliging of American snakes to signal their presence. Our Aussie snakes are not so considerate.

A mate of Doug’s, Jay Jensen was able to climb with me and we had a great day on this 1,000-foot buttress. While up there it was hard not to notice Adams Rib the adjacent buttress, again put up by Doug and Galen with Chuck Kroger. Jay wasn’t able to make it, but Vern Clevenger was keen to make the ascent.

Vern and I were hauling arse up the approach gully when, at the halfway point, I reached a long table of rock straddling the gully with a dark void underneath. As I put my hand on the top to pull up onto it there was an ominous rattling from the blackness below. I peered into the darkness and there, a triangular head or two with a few coils, were shaking their rattles to inform me of their presence. I quickly headed to the right side of the table, thinking it was very obliging of American snakes to signal their presence. Our Aussie snakes are not so considerate.

|

The climb went well and all that remained was the trek back down the gully followed by a short walk across the desert to the car. Anticipation of another encounter with the rattlesnake den encroached my thoughts as I negotiated the rocky gully. But as I walked down, there was not so much as a rustle from the grass. I exhaled and finally allowed myself to relax, if not feeling a little annoyed that I had allowed myself to be "rattled" by that encounter.

We finally reached the flat desert and moved through the occasional grass and stunted bush patches. I was tired but on a high after such a great day. With our transport back to camp in sight, the ominous sound of a rattle woke me from my daydream. It was directly below my feet! I leapt about twenty feet in the air and seemingly landed about thirty feet away. Warning rattles are all well and good, but it also helps to be able to see the varmint too. I reckon my kingsnake-mate Alan would have enjoyed the pay-back of being an onlooker to this encounter. |

Furry with Teeth

|

Snakes are harmless enough, sort of? The main animals to be concerned about in Yosemite and the Sierras are the four limbed ones, such as raccoons and black bears. These are great foragers and can rip a tent apart if they smell the slightest aroma of food. I had the arse end of my tent chewed out by a raccoon because I inadvertently left a tube of toothpaste in it while out climbing. The Yosemite climbers use steel ammunition boxes and chests for food storage but the blow-ins like me had to improvise by hoisting their storage bags up over a convenient tree branch.

Ed Ward-Drummond, the English climber, was camping near me and over breakfast told me that he had had a broken sleep. It seems that during the night while cutting zzzz’s he heard a scrambling, then silence, followed shortly afterwards by the ground shaking like the San Andreas fault had finally slipped. Another moment of silence then scrabble, scrabble, scrabble. Silence, then the ground shook again. This happened about four or five times before he decided he should leave his warm pit and investigate. |

|

His food store was hanging about 25 feet up and 5-to-10 feet from the trunk of a tree. It turned out that a black bear was scrabbling up the tree trunk until it was level with his bag, and then it launched itself at the bag, missing, then falling to the ground right beside his tent — an American version of the Australian "Drop Bear" perhaps? Except America's is real. Aussies delight in telling visitors to our fair shores that carnivorous koala bears with fangs drop out of the trees onto you in ambush style. Bloody Australians, full of BS!

There was another bear that was hanging around, it was mean, hungry, and looking for trouble. The bear eventually went to the back of a VW Kombi parked near Camp 4, underclung the back window with its claws with an impeccable climbing style, then reefed it open. It reached in, grabbed a can of baked beans, bit the top off and then licked the contents from the can. California black bears are basically small and look very friendly, cuddly even (though certainly bigger than the bears we have in Australia, everyone wants to hug a koala.) On witnessing the power of this one, it provided an important warning never to meet up with one of its cousins, a grizzly, polar bear or even an angry black bear in the wild. |

Creatures Down Under

|

While Australia has its fair share of sharp-toothed and highly venomous creatures, and we joke with foreigners, "don't touch that, it'll kill ya'," surprisingly I have had very few encounters with these dangerous creatures while climbing.

My worst Aussie experience with a snake was while I was belaying my friend at the base of a cliff surrounded by some thick bush near Blackheath in the Blue Mountains west of Sydney. I was tied to a tree while belaying and decided to step across a small shrub into a more comfortable position. As I stepped, I looked down to see a large two-metre (6.5 feet) coiled diamond snake all dressed in a newly acquired black and white silken coat. I quickly moved back but being tied on with a short leash, I hoped that my slithering neighbour would remain on its side of the small bush. Most people, including yours truly, do not like to be hog-tied cheek-by-jowl with a snake, even one that is non-poisonous. While diamond snakes are pythons, they are a large powerful snake that if, so inclined, can inflict a nasty bite. After my climbing companion reached his belay stance, I gingerly checked the other side of the shrub, but my erstwhile friend had disappeared. But to where? Not one to take any chances I quickly ascended the rock knowing that at least on a vertical cliff I would be safe – maybe? The tiger snake, which is extremely venomous, aggressive, and agile, have been encountered by many a climber on the cliff. A climber in the Australian Capital Territory was bitten by one when he inserted his finger into a crack; fortunately, he lived to tell the tale. And Common Climber's own Dave Barnes has a quite entertaining tale of his encounter with a tiger snake whilst on a climb. |

But the tiger snake isn't the only poisonous Aussie snake that climbs. The broad-headed snake is found around Sydney, and it likes lying in the sun on sandstone ledges. It is often mistaken for a diamond python, but has an enlarged head to accommodate its outsized venom glands. Here is an account of a broad-headed snake encounter while on the wall.

Climbing Messiahs Exit (5.10a/18) at Mt Piddington NSW, I had a memorable serpentine encounter. Pulling through the steep crux I placed a good wire. I felt really solid and contemplated soloing the route in the future. Moving up easier ground to a large horizontal break, I felt something soft, and it moved – SNAKE! At that I was off! I glanced up to see a venomous Broad-headed Snake. I was so lucky for the good wire and for not grabbing that large head. My thoughts of soloing quickly diminished as I moved up with great caution past the snake and onto the final belay. My partner, Harry Luxford took a very wide detour to avoid the snake as he followed”.

-- Bruce Cameron

|

Similarly, I have not met all that many four-footed creatures while climbing in Oz although one incident stands out.

I was putting up a first ascent, at Blackheath in the Blue Mountains and had placed a peg runner below some overhanging rock leading to an extensive horizontal break. Clipping in, I surveyed the ground above, called out “Watch me,” then proceeded to tackle the intervening steep space on small holds. I was just about to grab the edge of the slot when I was confronted by the arse end of a possum perched on the edge of the ledge. Ring or brush tail you might ask? I wouldn’t have a clue because next moment it urinated all over me then pissed off along the ledge. I teetered for a moment but managed to hang on. My brother on belay was laughing so much that it took some time before he was able to commiserate of sorts by saying, “Luckily, it wasn’t a skunk.” Thanks Bro! |

There are other four-legged critters that maraud climbers in Australia. Throughout the 1970’s when we could camp at the top of the walkdown area at Frog Buttress our tents were quite often invaded by large goannas (lace monitors) seeking food, particularly eggs. These large lizards can reach two metres (over 6 feet) in length and weigh in at 14 kilograms (31 pounds).

|

Once when I was climbing in the Warrumbungle National Park and staying at a Balor Hut, Ray Lassman and a friend from work went up to climb Rib and Gully (13/5.5) on Crater Bluff. As I had climbed the route on previous occasions, I decided to take a break so that they could make a faster ascent. As I sat on a bunk with sunlight streaming in, a visitor appeared at the open door. The visitor looked quizzically to and fro then strode into the middle of the hut. I quickly dashed to the door and closed it leaving my uninvited caller locked inside. Once outside some unsavoury and reprehensible thoughts came to mind.

My first thought was to play a joke on my friends when they returned. I figured my captured visitor would make a beeline for the door as they opened it, thereby giving them a scare. At this stage though my cunning (and totally shameful) plan was to be foiled. The large goanna I had entrapped inside had decided to make a goal break and sounded like it was going to demolish the hut. Sheets of corrugated metal creaked and groaned as it expanded and contracted its strong muscles between the hut’s wooden frames and the sheets. In the end I had to relent; I opened the door. Unharmed but quite rightly decidedly peeved, the reptile stepped into the opening, gave me a filthy look, then headed straight for the nearest tree and clambered up it. I was somewhat admonished when I related this devious, underhanded plan to Ray. He looked me straight in the eye and said, “You would not have done that to us.” In some sort of weak defence now, I can only say, it was the early 1970’s and I was much younger then? |

Centipedes, Spiders and Phasmids, Oh My

There are other creatures that have a large number of legs. In the Blue Mountains west of Sydney I can remember one incident where I had the crap scared out of me by one of these. Firebug (17/5.9), at Mt. Boyce near the town of Blackheath, is an aptly named climb to encounter a many-legged creature. Put up by John Ewbank with John Fantini, it was named after the fire that almost got away when they had liberally applied some petrol followed by a match to eliminate some offending vegetation.

Ray Lassman, Bryden Allen, and I made the second ascent in the late 1960’s. I scored the first and third pitch, the latter being the crux. This pitch negotiates some blocks, then goes directly up a steep corner topping out on a slippery, sloping ledge that is a half-inward, elongated ellipse that looks like a reasonable half scale replica of the Indianapolis 500 circuit or a cycling velodrome. And a racing circuit it was, for as I put both hands on the slope, I saw a blur in the corner of my left eye. In a flash, the biggest, hairiest spider that I have ever seen, zoomed across the circuit, hurdled my hands then, fortunately, kept zooming right until it was out of sight. Even though I was looking up at easier ground above, my heart skipped a beat or three and the climb instantly was assigned a new grade of 21 (5.10d) as I struggled against the pull of gravity, albeit successfully. Rather than the tried-and-true measure of outstretched arms used by fishermen to communicate the size of their catch, just let it be said that a person’s fist would seem a reasonable gauge of this hairy arachnid's size.

Balls Pyramid also has many-legged denizens besides the birds that confront climbers (see Animal Acts Part 1: Things With Wings). The two types of lizards found on it, a skink and a gecko, are small and friendly critters.

Ray Lassman, Bryden Allen, and I made the second ascent in the late 1960’s. I scored the first and third pitch, the latter being the crux. This pitch negotiates some blocks, then goes directly up a steep corner topping out on a slippery, sloping ledge that is a half-inward, elongated ellipse that looks like a reasonable half scale replica of the Indianapolis 500 circuit or a cycling velodrome. And a racing circuit it was, for as I put both hands on the slope, I saw a blur in the corner of my left eye. In a flash, the biggest, hairiest spider that I have ever seen, zoomed across the circuit, hurdled my hands then, fortunately, kept zooming right until it was out of sight. Even though I was looking up at easier ground above, my heart skipped a beat or three and the climb instantly was assigned a new grade of 21 (5.10d) as I struggled against the pull of gravity, albeit successfully. Rather than the tried-and-true measure of outstretched arms used by fishermen to communicate the size of their catch, just let it be said that a person’s fist would seem a reasonable gauge of this hairy arachnid's size.

Balls Pyramid also has many-legged denizens besides the birds that confront climbers (see Animal Acts Part 1: Things With Wings). The two types of lizards found on it, a skink and a gecko, are small and friendly critters.

Above photos: Click on the photos to enlarge and see captions.

Many insects and invertebrates inhabit the rock but only two really stand out. One looks like it might have auditioned for the role of the monster in Alien but is in fact a phasmid or stick insect; a benign and nocturnal inhabitant that is the rarest insect on Earth. This phasmid (Dryococelus australis) has a fascinating history; made extinct on its former home – the nearby Lord Howe Island - by the foundering of the S.S. Makambo. In 1918, the black rats on board, jumped ship and made it to shore to begin the depredation and the apparent extinction of the phasmid, as well as many of the island’s unique wildlife. In 1964 a dead insect was found by a climber on Gannet Green and another climber found two exoskeletons while climbing on the Pyramid in 1969. Was this credible evidence that the phasmid still survived on this isolated and hostile piece of rock?

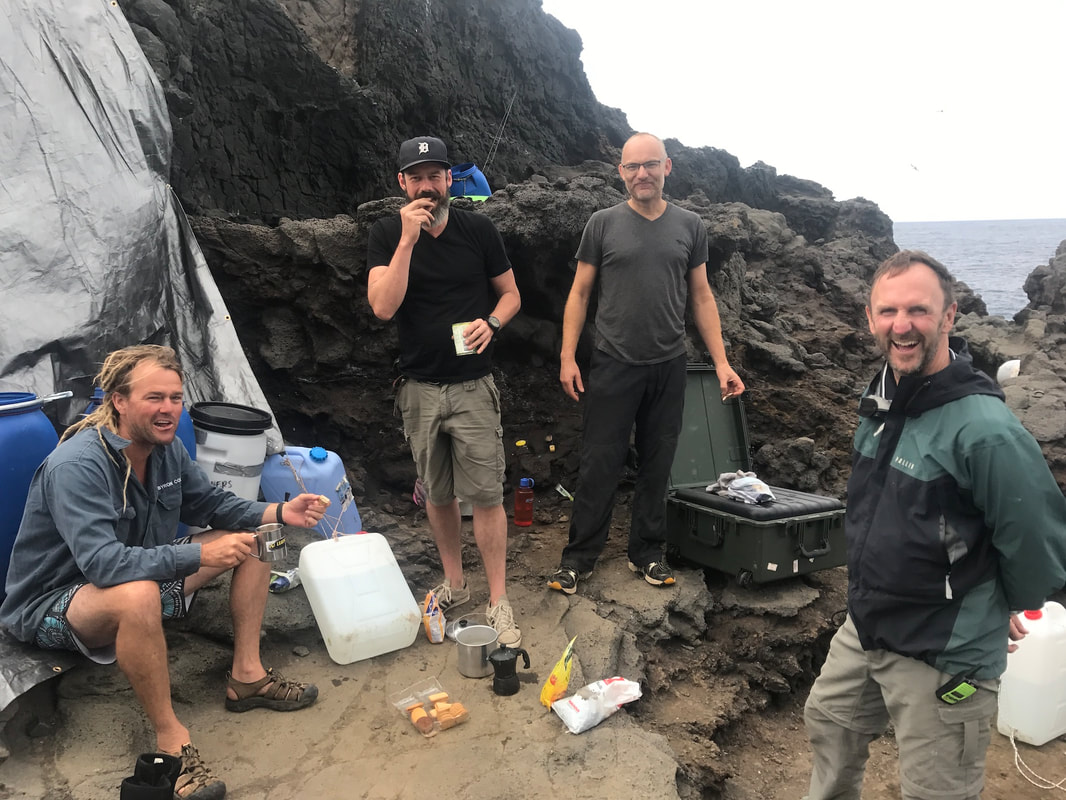

Later in the early 2000’s a tree was found below Gannet Green by scientists with a bevy of living specimens inhabiting it. Four insects were taken off and breeding programs were instituted in several Australian and overseas locations. The Melbourne Zoo has a highly successful breeding program, but a few years back there was a need for the introduction of new breeding stock. The Pyramid needed to be examined by people who could scale higher than Gannet Green, the absolute limit for most scientists.

Later in the early 2000’s a tree was found below Gannet Green by scientists with a bevy of living specimens inhabiting it. Four insects were taken off and breeding programs were instituted in several Australian and overseas locations. The Melbourne Zoo has a highly successful breeding program, but a few years back there was a need for the introduction of new breeding stock. The Pyramid needed to be examined by people who could scale higher than Gannet Green, the absolute limit for most scientists.

Above photos: Click on the photos to enlarge and see captions.

In 2017, a census of the southeast end of Balls Pyramid was undertaken by six climbers under the auspices of the Australian Museum. The group of climbers (of which I was fortunate to be one) and scientists found only 17 adult insects after much nocturnal searching. Interestingly, the locations of sightings ranged from above Gannet Green to almost the summit and surprisingly, the original tree was bereft of specimens. A female phasmid was taken off and transported to the Melbourne Zoo where she has since laid many fertilised eggs and contributed immeasurably to the genetics and continuance of this species.

The other insect is the stuff of nightmares. Many legged and up to 20 centimetres (8 inches) long, the centipedes found on the Pyramid have been subjected to the effects of gigantism, owing to having been marooned on an isolated island peak. Problematic at night, most expeditions have had somebody bitten by these arthropods, although only one of these experienced an allergic reaction. One climber was bitten on the lip while he slept, and the bites inflicted by these creatures are initially very painful and induce minor necrosis.

In 1970 on the West Ridge, John Worral and I had to strip the abseil ropes coming off the summit. Two thirds of the way back along the traverse to the fixed abseil rope, we were overtaken by darkness. We needed to bivvy there, perched on tiny ledges about ten metres apart, without food, water, shelter or warm clothes. Then a light rain began to fall. Could it get worse? It did – for John!

All night John yelled, slapped and swiped in sudden convulsions that would wake me just as I was dozing off. Centipedes apparently crawled under his clothing and bit him repeatedly. Maybe John was laying over a centipede den of some sort or blocking their nightly migration path. I don't know. All I know is that I was untouched by them. Although between the rain, cold, and John's sudden outbursts, it was certainly a long and dismal night.

At around 2:00 a.m., I woke to another physical and vocal explosion from John. "Bugger!" he cried. Groggily, I looked around and saw a large cruise ship sail past the Pyramid with lights blazing. Perched high on our small stances with rain dripping from our clothes, we fantasised about the shelter, food, warm beds, and hot tea - or some other stronger beverage - as the cruise liner went steaming past. And, no doubt, John was also thinking of a centipede-free environment.

The other insect is the stuff of nightmares. Many legged and up to 20 centimetres (8 inches) long, the centipedes found on the Pyramid have been subjected to the effects of gigantism, owing to having been marooned on an isolated island peak. Problematic at night, most expeditions have had somebody bitten by these arthropods, although only one of these experienced an allergic reaction. One climber was bitten on the lip while he slept, and the bites inflicted by these creatures are initially very painful and induce minor necrosis.

In 1970 on the West Ridge, John Worral and I had to strip the abseil ropes coming off the summit. Two thirds of the way back along the traverse to the fixed abseil rope, we were overtaken by darkness. We needed to bivvy there, perched on tiny ledges about ten metres apart, without food, water, shelter or warm clothes. Then a light rain began to fall. Could it get worse? It did – for John!

All night John yelled, slapped and swiped in sudden convulsions that would wake me just as I was dozing off. Centipedes apparently crawled under his clothing and bit him repeatedly. Maybe John was laying over a centipede den of some sort or blocking their nightly migration path. I don't know. All I know is that I was untouched by them. Although between the rain, cold, and John's sudden outbursts, it was certainly a long and dismal night.

At around 2:00 a.m., I woke to another physical and vocal explosion from John. "Bugger!" he cried. Groggily, I looked around and saw a large cruise ship sail past the Pyramid with lights blazing. Perched high on our small stances with rain dripping from our clothes, we fantasised about the shelter, food, warm beds, and hot tea - or some other stronger beverage - as the cruise liner went steaming past. And, no doubt, John was also thinking of a centipede-free environment.

Video of the Phasmid Expedition

(with an interview of author Keith Bell)

My thanks to the Australian Museum and the Melbourne Zoo for kindly allowing the use of photographs and material relating to the 2017 Balls Pyramid Expedition and the Phasmid breeding program at the Zoo.

Thanks also to Rohan Cleave of the Melbourne Zoo and Ian Hutton of the Lord Howe Island Museum for allowing me to use their amazing images. I am also indebted to Rohan for showing me around the Zoo's phasmid breeding facility; the dedication of he and his staff are beyond words.

And to fellow expeditioner, photographer Tom Bannigan who edited the extraordinary video from footage he captured as a member of the Australian Museum Expedition to Balls Pyramid in its search for the Lord Howe Island Phasmid.

Thanks also to Rohan Cleave of the Melbourne Zoo and Ian Hutton of the Lord Howe Island Museum for allowing me to use their amazing images. I am also indebted to Rohan for showing me around the Zoo's phasmid breeding facility; the dedication of he and his staff are beyond words.

And to fellow expeditioner, photographer Tom Bannigan who edited the extraordinary video from footage he captured as a member of the Australian Museum Expedition to Balls Pyramid in its search for the Lord Howe Island Phasmid.