|

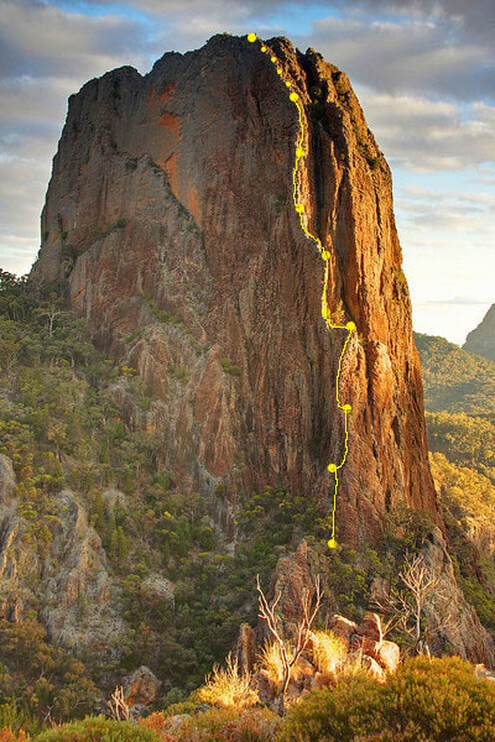

Cover Photo: By Simon Carter

Vale Bryden Allen - a legend of Australian climbing, who established classics along the East Coast of the continent (even preparing the ground for John Ewbank) and into the remote southern sea, creating and bringing the latest in climbing tools to Down Under (including the infamous Australian carrot), and spreading the spirit of camaraderie in climbing both before and after a debilitating accident that put him in a wheelchair - has passed. Join us in this special tribute to Bryden given by fellow first ascentionist Keith Bell, who followed in Bryden's footsteps both literally and figuratively. Keith considers Bryden a mentor and friend and here, shares the incredible story of Vale Bryden Allen.

Vale Bryden Allen February 28, 1940 to February 9, 2022 |

|

|

Bryden Allen arrived in Australia [in the early 1960’s]. With him came alloy karabiners, P.A.’s [friction boots], double ropes and his experience on many hard climbs in England. Bryden’s dynamic attitude and skill forced many great lines in The Grose, Warrumbungles and other cliffs." (John Ewbank, Rockclimbs in the Blue Mountains, 1967, Pages 6 – 7)

|

Scientist, mathematician, sociologist, writer, thinker, inventor, musician, dancer, singer, and rock climber: Vale Bryden Allen was an eclectic mix that was fueled by an endearing eccentricity which warmly welcomed and encouraged others to indulge in some, if not all his passions. Born in Canberra, Australia Bryden moved to England with his family when he was eleven years old, returning about twenty years later to live in Sydney. Bryden achieved legendary status as Australia’s pre-eminent rock climber while keeping his feet on the ground to be a good friend, mentor, and inspirational figure to all Aussie climbers.

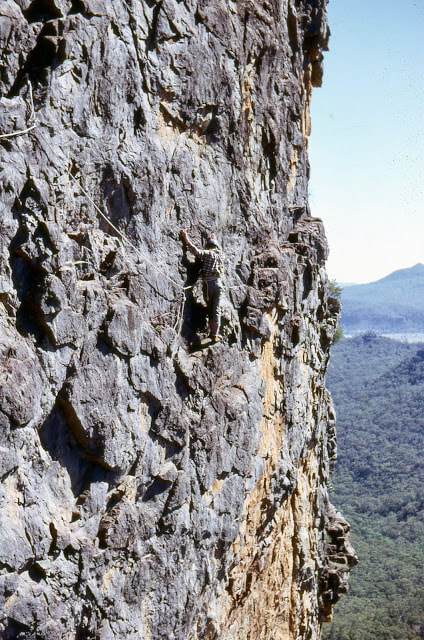

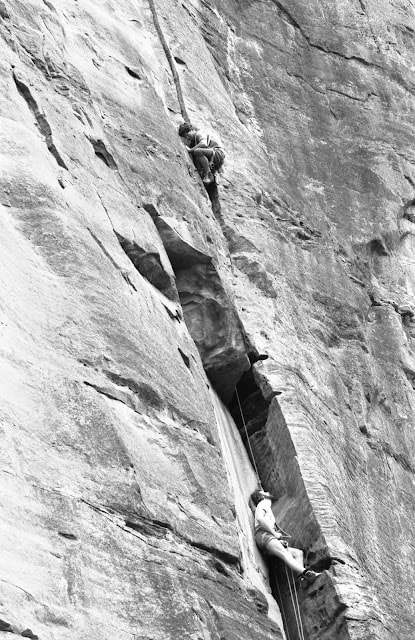

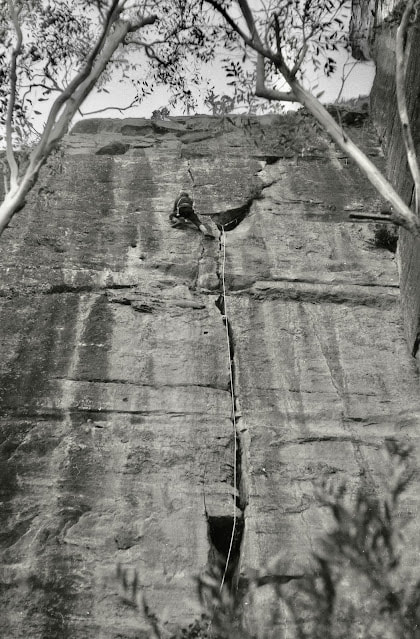

Bryden began leaving his mark in the climbing world as early as 1962 in the Warrumbungle Range. In partnership with Ted Batty, he put up classics such as Cornerstone Rib (14/5.6) on Crater Bluff, Out and Beyond (16/5.8) on Belougery’s Spire, along with many other climbs. Their piece de resistance, Lieben (17/5.9) was put up a year later. For protection, Bryden tied string around blocks and tried placing soft steel pitons into the fused cracks of Crater Bluff while Ted Batty seconded in sand shoes! This climb on Crater’s west face went through steep, uncompromising territory and for many years was the hardest climb in Australia. It is still considered a solid, thought-provoking test piece. Around the same time, Bryden put up new climbs in the Blue Mountains:

|

We invite you read Keith Bell's entertaining stories about the legendary climb Lieben:

- + Animal Acts Part 1: Things with Wings

- + Tiptoeing Through Some Bungles

In 1963 he also found time to assemble and print his seminal guidebook, The Rock Climbs of NSW (New South Wales), not an easy undertaking in a pre-computer environment. This publication provided the foundation for John Ewbank’s 1967 guide, as well as for all Australian guides since. Bryden also invented and perfected the carrot and bracket bolt system used for many years by climbers to provide safe protection, particularly in the Blue Mountains.

But, it was the magnificent triptych that he assembled in the mid 1960’s that proved to be his masterpiece. These were the climbs that Bryden was most proud of, scaling the three highest unclimbed faces to be found Down Under:

But, it was the magnificent triptych that he assembled in the mid 1960’s that proved to be his masterpiece. These were the climbs that Bryden was most proud of, scaling the three highest unclimbed faces to be found Down Under:

- Elijah (17/5.9) on Bluff Mountain (Warrumbungle Mountains)

- A Toi la Glorie - Thine be the Glory, (17/5.9) on Frenchmans Cap (Cental WesternTasmania) and

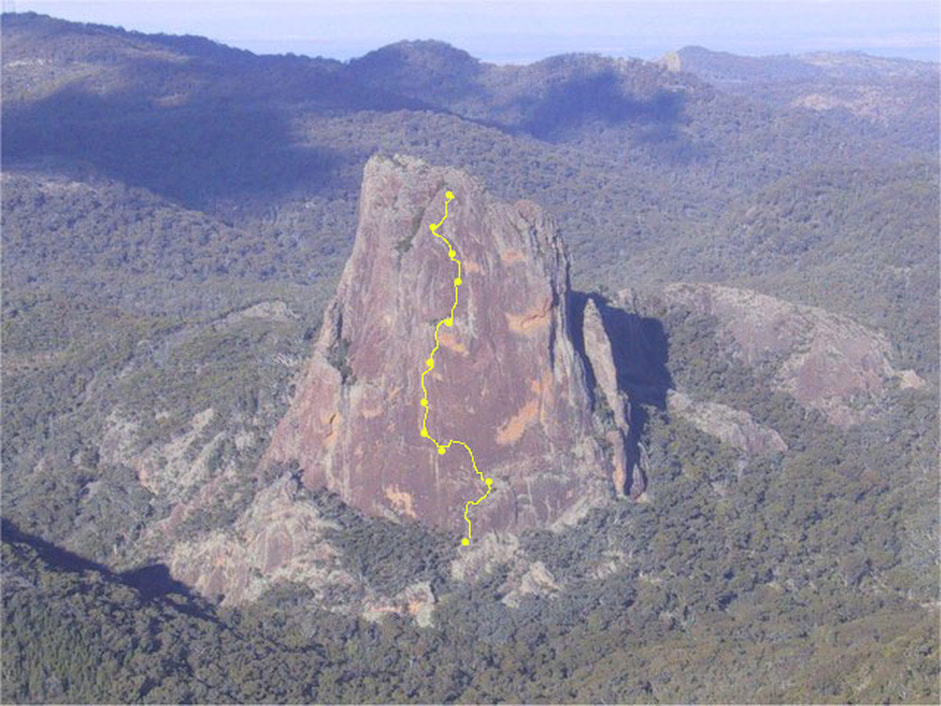

- The SE Ridge on Balls Pyramid (the world’s tallest sea stack at 560 metres/1840 feet) near Lord Howe Island.

“To establish a first ascent is to create a work,

Dare one say, of art?”

-- Bob McMahon 2012

The first panel of the composition, Elijah on Bluff Mountain was climbed in May 1964 by a 24-year-old Bryden accompanied by a brash 16-year-old - John Ewbank. Characterised by short pitches and difficult route finding, it was a tour de force. Its fourteen solid pitches never relent making it a serious undertaking even today. Later, they went on to add the equally impressive Stonewall Jackson (20/5.10c) and Ginsberg (19/5.10b) in 1969 on this remarkable trachyte cliff.

Bryden shared a story about the ascent of Elijah that he often chuckled about. While high on the face of Bluff Mountain, Bryden thought that a bolt or two should be placed to enhance the anchor that John had constructed. John strenuously defended the multi-nut belay he had assembled, so Bryden acquiesced and led off. Some metres above, Bryden had just placed a runner, clipped in, and was starting to traverse away from it when he felt a fearful tug. It transpired that John’s “solid” belay nuts had failed, and he had fallen off the ledge. Bryden always maintained with a big smile that this was a great example of the climbing leader belaying a falling second who should be belaying him.

For many years, this climb had its start defined by a worn-out pair of Bryden’s deteriorating P.A. friction boots hanging by their laces off a small flake. Maybe they were the original pair that he brought from England?

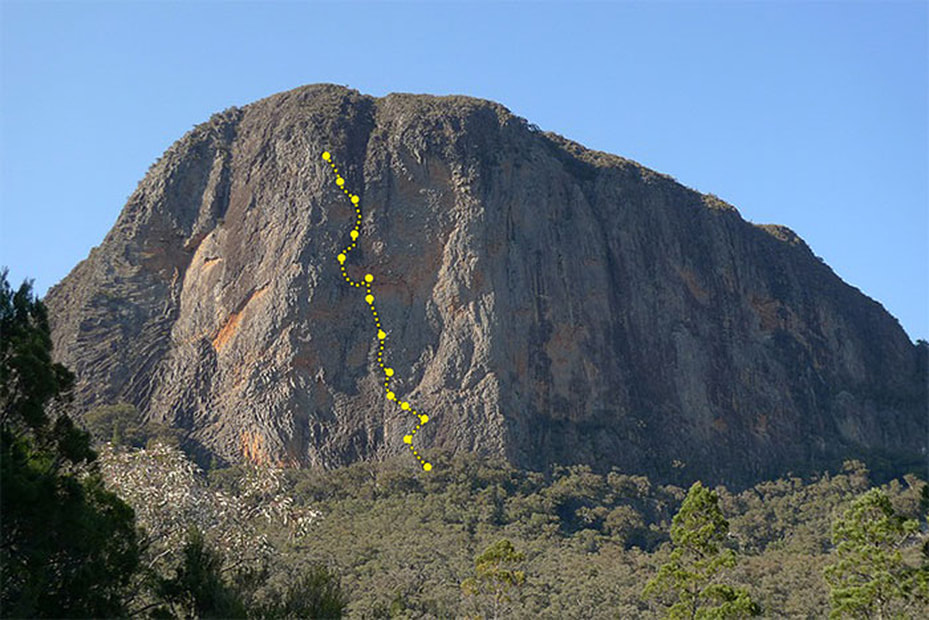

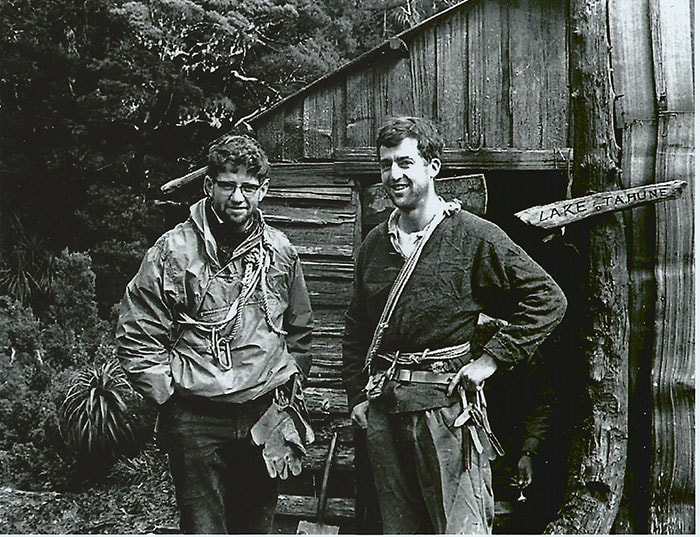

The central panel of the triptych was A Toi la Glorie - Thine be the Glory, (17/5.9) on Frenchmans Cap (Tasmania), this time with Jack Pettigrew on the 7th of January 1965. It was the first route up Frenchman’s imposing East Face; a formidable and committing achievement considering the limited climbing equipment available at the time, its remoteness, and notoriously inclement weather. The climb is now simply known as The Sydney Route.

For many years, this climb had its start defined by a worn-out pair of Bryden’s deteriorating P.A. friction boots hanging by their laces off a small flake. Maybe they were the original pair that he brought from England?

The central panel of the triptych was A Toi la Glorie - Thine be the Glory, (17/5.9) on Frenchmans Cap (Tasmania), this time with Jack Pettigrew on the 7th of January 1965. It was the first route up Frenchman’s imposing East Face; a formidable and committing achievement considering the limited climbing equipment available at the time, its remoteness, and notoriously inclement weather. The climb is now simply known as The Sydney Route.

|

|

The first 900 feet was delightful climbing ... there were great slabs, delicate bridging in open chimneys, jams, laybacks and mantelshelves. The pitches were long, but protection was there if you looked for it. The next section was most serious and would have to wait for fine weather. |

The last panel was completed when Bryden and Dave Witham reached the summit of Balls Pyramid on St. Valentine’s Day in 1965. Along with Bryden and Dave, John Davis and Jack Pettigrew also made the top. Back on Lord Howe Island after the ascent, Bryden was interviewed by the Signal - Lord Howe Island’s newspaper.

BASE CAMP, Balls Pyramid, Monday - 15th February 1965 |

When we established that we could go around Winklesteins Steeple (a face about 1,000 feet above sea level that had been halted previous attempts by another party) there was never any doubt that we would reach the top. The summit is a concave area about 20 feet in diameter. There is some coarse grass in parts, and we found enough stones to build a cairn. Sea birds are all over the Pyramid and we found a baby gannet in the highest point. The breathtaking view was marvellous …”

-- Bryden Allen

The expedition’s route on the SE Ridge faces away from Lord Howe Island with a 300-degree view of a lonely and empty sea. In the mid 1960’s and even into the 1970’s it felt a remote and isolated part of the planet on which to be ‘marooned.'

These three diverse and geographically scattered routes climbed in less than eight months rank, in my opinion, as the most impressive feat in Australian climbing history.

These three diverse and geographically scattered routes climbed in less than eight months rank, in my opinion, as the most impressive feat in Australian climbing history.

To watch Bryden on rock was to witness the delicacy of a ballet dancer, the precision of a technician and the cunning of a fox. He left me in awe, embodying everything a climber should be.”

-- Colin Monteath 2022

Bryden continued to climb until the end of the twentieth century with hard climbers, weekend climbers and novices. Many people have written about their experiences climbing or indulging in other outdoor activities with him and I am one of their number.

My first trip through the leisurely and picturesque Wollangambe Canyon was with a group led by Bryden. I probably first met Bryden at Lindfield Rocks where many Sydney climbers would congregate for practice late on Wednesday afternoons in the late 1960’s. Bryden was the master of Abseil Wall, an extremely delicate wall with minimal holds that he soloed with apparent ease. Most nights though he was matched by Ray Lassman who was also no slouch on a boulder. Watching their competitive streaks emerge on the Abseil Wall variants was always fun for us in the gallery.

When I and a few others expressed our intention to mount an expedition to Balls Pyramid in 1970, Bryden was the first to step forward with advice and helpful suggestions. While we were going to repeat the SE Ridge, it was Bryden who recommended that we give the other unclimbed ridge a go. Going to the obviously harder, steeper end was a great piece of advice, but also one that induced a few nightmares even before we reached the rock. This got worse as we approached the Pyramid on the boat as the ridge started to loom ominously above us, but our fate was sealed – thanks Bryden.

My first trip through the leisurely and picturesque Wollangambe Canyon was with a group led by Bryden. I probably first met Bryden at Lindfield Rocks where many Sydney climbers would congregate for practice late on Wednesday afternoons in the late 1960’s. Bryden was the master of Abseil Wall, an extremely delicate wall with minimal holds that he soloed with apparent ease. Most nights though he was matched by Ray Lassman who was also no slouch on a boulder. Watching their competitive streaks emerge on the Abseil Wall variants was always fun for us in the gallery.

When I and a few others expressed our intention to mount an expedition to Balls Pyramid in 1970, Bryden was the first to step forward with advice and helpful suggestions. While we were going to repeat the SE Ridge, it was Bryden who recommended that we give the other unclimbed ridge a go. Going to the obviously harder, steeper end was a great piece of advice, but also one that induced a few nightmares even before we reached the rock. This got worse as we approached the Pyramid on the boat as the ridge started to loom ominously above us, but our fate was sealed – thanks Bryden.

Read Keith Bell's accounts of climbing Ball's Pyramid: + Animal Acts 2: Things that Slither, Crawl, and Walk |

|

A couple years later he offered similar help and advice by suggesting that I should venture onto Bluff Mountain – Gulp!

It was Bryden’s suggestion really that we have a look at Bluff Mountain. One could hardly refuse the invitation after Bryden had sportingly lent us his well-fondled super postage stamp size photo of the mountain with all the exciting routes marked”.

-- Keith Bell, in Brewer’s Droop, Thrutch magazine, vol. 61, September 1973, pp. 26.

Nowadays a climber can easily download heaps of information on Bluff Mountain or nearly any crag or climb in the world. It is probably very difficult for young climbers to imagine the primitive state of the art back in the 1960’s and into the 1970’s when traditional climbing and "ground up" first ascents ruled. Certainly, on Bryden’s earliest climbs including the BIG three, there were no harnesses, helmets, sticky rubber, cams, sewn slings or decent nuts or chocks. The pitons available were made from soft steel of European origin and pre-dated the superior American chrome-molly by many years.

|

My first memory of climbing with Bryden was alternate leading up Excalibur (17/5.9) on Old Baldy in the Wolgan and eliminating the aid used by John Ewbank. I also recall climbing the second ascent of Firebug (17/5.9) with Bryden and Ray Lassman at Mt Boyce and then going on to make the second ascent and eliminating aid on Goldstar(18/5.10a) later in the day. On another weekend Bryden and I climbed the first ascent of Hydra (20/5.10c) near Hercules (18/5.10a) at Perpendicular Rock and enjoyed a pleasant weekend camping beside the Wollondilly River south of Sydney.

Bryden also made the second ascent of Caladan (20/5.10c) at Ikara Head near Mount Victoria with Pete Giles, Ian ‘Humzoo’ Thomas, with me in tow. Clockwork Orange (20/10c) at Lower Shipley was another early ascent where we shared leads. Bryden was such a relaxed character, even singing his favourite songs with gusto as he easily swung up through the crux. Many people remember this aspect of Bryden’s climbing. On dusk after climbing, he would often sit on a rock near the edge of the cliff and play lilting tunes on a fife or recorder. I have pleasant memories of him doing this at Frog Buttress in Queensland when we were able to camp very close to the cliff edge. I was present when Bryden made an early ascent of Janicepts (21/5.10d), then regarded to be the hardest climb in Australia. As nobody followed Bryden, he was also forced to remove the gear that he had placed by abseiling and retrieving it himself. Bryden had an advant garde abseiling setup. He used the “Crossed Carabiner” method with an unusual twist. Instead of a carabiner or angle piton providing the friction to the rope, Bryden used his piton hammer handle. As he was removing gear from the top wall, he experienced problems getting a nut out. Bryden immediately whipped out his piton hammer to aid with the extraction but then realised he had uncoupled himself from the abseil rope. For a rather fraught moment or two he hung onto the ropes before getting them back through the carabiners and secured. For the rest of his descent he removed all the remaining nuts by hand. Not much fazed Bryden! In 1972 Bryden took on the Kraken (22/5.11a) at Mount Piddington, eliminating the aid that John Ewbank had used on its first ascent. Kraken is an intimidating and unusual crack climb. After successfully completing the ascent Bryden had to rush back to Sydney for his Morris dancing practice (a form of costumed English folk dance). Although I joined in many of the things that Bryden enjoyed, Morris dancing practice was a step too far for me. However, I did go with him to Sydney University for Greek dancing and must say that I really enjoyed it - although I danced with two left feet. In the early 1970’s he also turned his attention to Booroomba Rocks, a towering granite crag to the south of his old hometown, Canberra. Further Out (19/5.10b), Jubilate (18/5.10a) and The Bleeder (17/5.9) were the result. The former two were long unprotected climbs on small holds up steep slabs. The latter, a shorter, steep jam crack was described in the guidebook as “Horrible and harder than 17 for a human being," a comment perhaps of Bryden’s superlative style, particularly on cracks. |

|

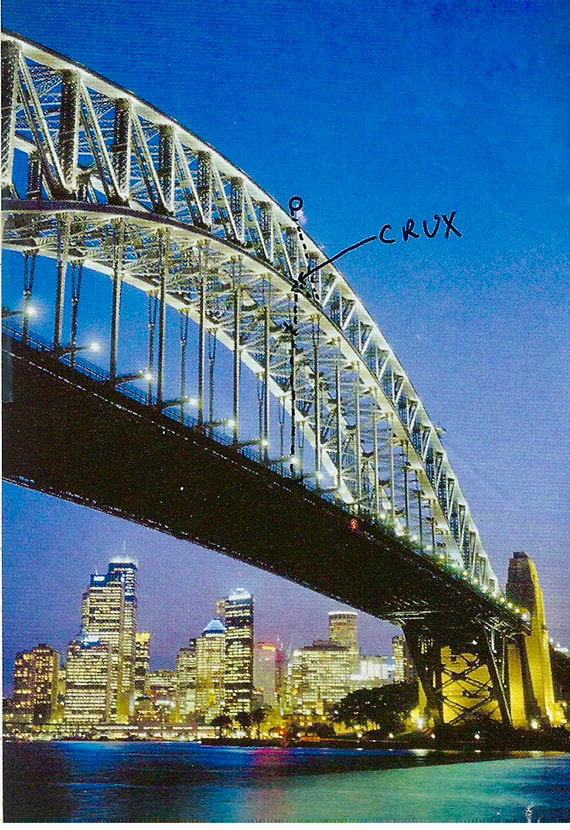

Bryden’s first ascents were not just in the Blue Mountains, but some were very close to home located within the soaring skyline of Sydney’s Central Business District. “Buildering” offered big challenges - nocturnal, technical, physical, and legal - that Bryden could not ignore. With consummate skill and guile, he made ascents of the Sydney Town Hall, Central Railway, and the Lands Department Clock Towers, the futuristic Centre-Point Tower, and of course the Sydney Harbour Bridge.

Above photos: Hover over image or click to see captions, click on photos to enlarge. (Photo Credits: https://www.brydenallen.com)

|

Again, he loved to recount that as he was drilling a bolt hole into the sandstone of the Sydney Town Hall late at night with a Sebco (hand) drill and hammer, his accomplice signaled that a policeman was approaching on the footpath below. Bryden remained poised while the “copper” remained paused directly below his perch for seemingly too many minutes. Fortunately, the officer eventually moved on and Bryden continued placing the bolt into the building. While most of us climbed the bridge via the arch, Bryden, forever the pathfinder, climbed directly to the summit up its thin central support column, the ultimate directissima - an awesome and exposed route.

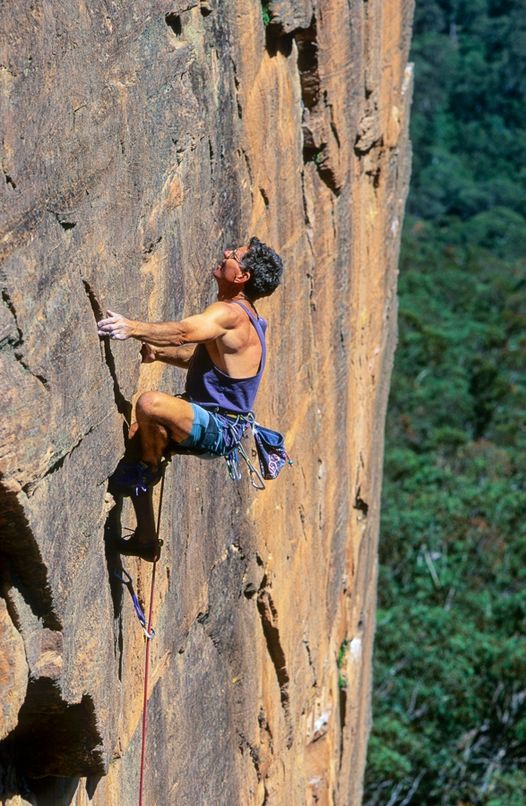

In 1990 I moved to Canberra and lost almost all contact with Bryden for over a decade. But the “tom toms” of the climbing scene are always active and before the turn of the century I saw an amazing photo that Simon Carter had taken of Bryden. Bryden loved this photo and it featured prominently in the books that he published. “I took this image of [Bryden] in 1998, when he was at the age of 58, climbing as hard as - or harder than ever on the route Toyland (25/5.11d), at Cosmic Country in [the} Blue Mountains. Something I found super inspiring at the time – and still do!” Simon Carter And then, a life changing event. It began with a climbing trip to Arapiles.

“[Bryden] and Chris Jackson set out from the camp-site one wet day intending to climb something overhanging that would be relatively dry. While scrambling up some rock to inspect the climb and check that the crux wasn’t wet [Bryden] slipped. He fell and hit a small ledge that sent him backwards, dropped another four metres and landed on his back over a sharp rock.” Peter Chaly in Rock Magazine Bryden, a person who had prized fitness and physical abilities had become a paraplegic on relatively easy ground at the back of the Pharos in a freak accident that could have happened to anybody. |

The period after the year 2000, until his recent death, was undoubtedly his greatest test and his mightiest achievement. It was not on rock but in a wheelchair where Bryden triumphed. Though confined to a wheelchair for the next 22 years Bryden showed a joy de livre sangfroid and independence that was truly inspirational. He continued exercising and kept amazingly fit. He wrote, he busked (solely for the joy of doing it), he attended meetings and book launches, always keeping in contact with friends and family. Like a father figure he remained in touch with the climbing community by visiting the local climbing gym where he kindly belayed me and many others on the walls. On these nights he would wheel around, meeting, talking with, and helping people.

An amazing character with amazing stories. His presence and belays at the gym will be sorely missed”.

-- Al Clarence, gym member

Photos Above (click to enlarge): Bryden at the launch of a book on Balls Pyramid in 2016 at the St Peter’s climbing gym in Sydney. (Photo Credit: Keri Bell)

He also organised a Boulder and BBQ Day at Lindfield Rocks that I attended from Canberra on several occasions.

I saw a lot of Bryden over the last decade and never once did I hear him feel sorry for himself. He was always the old bubbly Bryden, no recriminations, no self-pity, always reliable, the brilliant climber, an innovator, a visionary, and a man with a plan to improve the lot of humanity, who just happened to be seated in a wheelchair. No doubt they broke the mould when they made Bryden.

He touched many people in the climbing world as well as in other spheres. I think the thoughts of his good friend, written below, sum up Bryden - the person - for many of us.

“All my memories of him cause a smile - and somehow, I think that’s a great legacy to leave”. Sue Royce (Atkinson), a good friend from his early days in the Sydney Rockclimbing Club (SRC).

Bryden, ever the thinker and the spiritual man of the outdoors would probably choose this, a passage of his favourite hymn as an epitaph.

“Not for ever in green pastures do we ask our way to be;

But the steep and rugged pathways may we tread rejoicingly”.

My friend, you did that so well and you remain an inspiration to me and to so many others.

I saw a lot of Bryden over the last decade and never once did I hear him feel sorry for himself. He was always the old bubbly Bryden, no recriminations, no self-pity, always reliable, the brilliant climber, an innovator, a visionary, and a man with a plan to improve the lot of humanity, who just happened to be seated in a wheelchair. No doubt they broke the mould when they made Bryden.

He touched many people in the climbing world as well as in other spheres. I think the thoughts of his good friend, written below, sum up Bryden - the person - for many of us.

“All my memories of him cause a smile - and somehow, I think that’s a great legacy to leave”. Sue Royce (Atkinson), a good friend from his early days in the Sydney Rockclimbing Club (SRC).

Bryden, ever the thinker and the spiritual man of the outdoors would probably choose this, a passage of his favourite hymn as an epitaph.

“Not for ever in green pastures do we ask our way to be;

But the steep and rugged pathways may we tread rejoicingly”.

My friend, you did that so well and you remain an inspiration to me and to so many others.

Rest in Peace.