Early in winter, after a week of precipitation, blizzards, and record-breaking storms, my partner Phil and I hiked into the mountains of Ben Lomond before dawn. For two unsuccessful years we had been chasing climbing-grade ice – uncommon in Tasmania - and ephemeral when it forms. This time, under a bluebird sky, we crested an unremarkable boulder field and stopped in our tracks, facing an immense wall of vertical ice across the valley. The sensation was one of sheer disbelief – like finding fossilised forests, or an Aurora at midnight, a legend that you hear about but never quite believe in until that magic happens.

The frozen plateau was treacherous, and a fractured rib acquired on the Port Davey Track three weeks earlier undermined my balance. Phil teasingly suggested a helmet. Overconfident, I laughed. He describes what happened next: “I turned around and you were face down in a rock pile under a giant bag and rope, squirming like a blue-tongue lizard.”

The frozen plateau was treacherous, and a fractured rib acquired on the Port Davey Track three weeks earlier undermined my balance. Phil teasingly suggested a helmet. Overconfident, I laughed. He describes what happened next: “I turned around and you were face down in a rock pile under a giant bag and rope, squirming like a blue-tongue lizard.”

|

After my concussion eased, I set up my bivvy in microspikes, and joined Phil on a sunset reccy.

We like to joke that we are the coldest Tasmanians in modern history, having been halfway up our tallest peak at sunrise on the day Tassie’s lowest temperature (−14.2 °C/6 °F) was recorded. More familiar Tasmanian cold involves an unrelenting, miserable, misty drizzle we call "mizzle." Mizzle pretends to be innocuous until you’re saturated, and then the wind kicks in. Against these conditions, Phil would tell you our snow bivvy was a comparatively dry and balmy −7 °C. Waking up was not balmy. As Phil melted snow and racked gear with offensive enthusiasm, I stole his belay jacket and layered it over mine. Buckles nipped at exposed fingers as I coaxed my harness over ski pants and heavy thermals. Phil had climbed with axes once before, leading a mixed route up a couloir in a style he laughingly calls "Tassie moist-tooling." |

Committed to dreams of winter ascents, on this trip he kitted himself out in shiny new Petzl equipment. I stuck loyally with my Charlet Moser axes and antique crampons, purchased second-hand on Gumtree from an ex-Antarctic scientist.

Compensating for inexperience, we set up top belays using top-rope trad anchors in dolerite boulders, aiming to follow the local ethic of preserving the ice while also preserving ourselves. Our first climb ascended a steeply-sloping ramp, easy terrain allowing playful movement on a new medium.

Unfamiliar equipment made our limbs awkward, and progress was slow. The third time I rested, weight on an axe, it fell out of the ice and onto my head. You might have expected my darling partner to be nice about the fact that I’d just adzed myself in the face, but Phil thought it was hysterical.

After this ego-leveling introduction, our second climb followed a near-vertical waterfall up the side wall of a shaded gully.

Compensating for inexperience, we set up top belays using top-rope trad anchors in dolerite boulders, aiming to follow the local ethic of preserving the ice while also preserving ourselves. Our first climb ascended a steeply-sloping ramp, easy terrain allowing playful movement on a new medium.

Unfamiliar equipment made our limbs awkward, and progress was slow. The third time I rested, weight on an axe, it fell out of the ice and onto my head. You might have expected my darling partner to be nice about the fact that I’d just adzed myself in the face, but Phil thought it was hysterical.

After this ego-leveling introduction, our second climb followed a near-vertical waterfall up the side wall of a shaded gully.

|

|

|

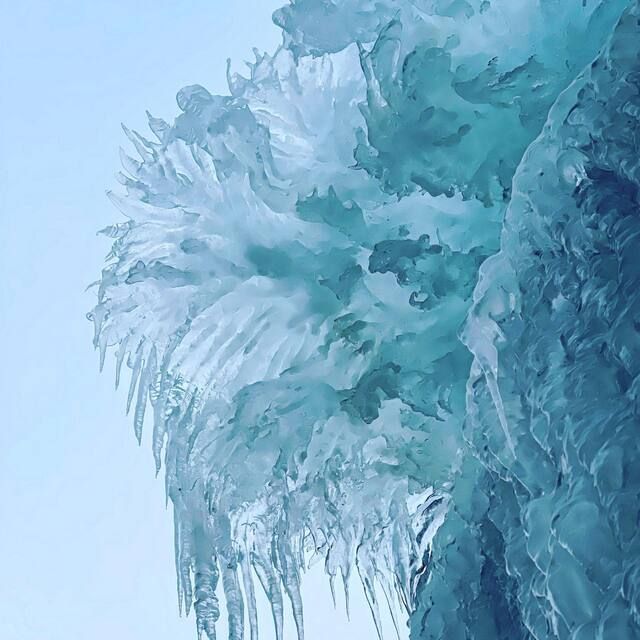

The route ascended twenty metres over a series of cascading bulges, bristling underneath with forearm-thick icicle teeth. This steeper terrain imposed a rapid learning curve on our front-pointing technique. Phil found the security of his crampons and axes astonishing, while I skidded on Bambi feet up most of the route.

We climbed this gully twice, and the second time felt like dancing. As we coiled ropes and clouds poured over the escarpment, Phil uncharacteristically suggested we might reach the car before dark if we left immediately. “Or…?” I prompted, sceptical. His eyes lit up: “Or, we could traverse the base of those waterfalls we found last night?” This was a slippery convex ledge of deep, clear ice, formed where a twenty-five metre (80 foot) icefall poured over a narrow rock shelf. Phil led the pitch, placing screws in bomber ice with audible delight. To our left, the world dropped away into boiling clouds; high above the waterfall spray had frozen like waves breaking against the sky. We climbed out elated, scoffed lukewarm thermos noodles while breaking camp, and hiked down to the car in darkness, casting moon-shadows. With overconfidence chastised, I wore microspikes until we’d dropped completely below the snow line. |

About

Phil and Tionne live together in Tasmania, where they can be found falling off surprisingly easy routes through the summer, or on remote multi-week winter hikes, probably in the rain. Phil is an intern Paramedic affectionately described as an ‘anti-faff trad daddy’ by his friends. He can be relied on to carry the stoke and more cams than he really needs. Tionne (the authors) is a trad fledgling employed in a gear store, having the time of her life when over-planning trip logistics and photographing their adventures.