This article is written by Dr. Szu-Ping Lee, a climber and professor in the Department of Physical Therapy at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas. His research focuses on the "biomechanical and neuromuscular control aspects of human movement. Specific research areas include: amputee rehabilitation, pathomechanics of disabilities, motor learning in rehabilitation, and sports science."

Amputation and limb loss is more common than people think. Currently in the U.S., it is estimated that more than 2.2 million of people live with limb loss (about 1 in 150) (Ref.1). This number will increase in the next 30 years to more than 3.6 million by 2050.

Nowadays, it is fairly common to see climbers with limb loss. I personally have met 2 climbers in Red Rock Canyon (on Black Track 5.9 and the ultra classic Crimson Chrysalis 5.8+). There are also a few famous climbers with limb loss, and good documentary films of their adventures. This article is to provide a basic introduction to prosthesis so you be in the know the next time you meet one of those badasses in the wild.

What is a prosthesis?

A prosthesis or artificial limb, is a device to replace the lost limb segment for someone with limb loss or born with limb difference. Depending on what is lost, a prosthesis varies in length and the number of joints. For example, someone who lost the leg below the knee will need to replace his calf, ankle, and foot; someone with an above-the-knee amputation will also need to have a knee joint. Certified prosthetists help to make these devices.

How does the prosthesis connect to the person?

This is a common question when people see a climber with a prosthesis: “How does the leg stay on?”, “What if the leg falls off?” A key design of any prosthesis is called the “suspension.” It keeps the prosthesis connected to the remaining leg even when the leg is not weighted and dangling in the air. (Note: the remaining leg is sometimes called “stump” but the correct name is “residual limb”.)

There are several different types of suspension design. Some designs use a strong suction and vacuum pump. Others wear a tight sock on their residual limb that has a pin at the end. The pin is then inserted into the prosthesis (Figure 1).

Nowadays, it is fairly common to see climbers with limb loss. I personally have met 2 climbers in Red Rock Canyon (on Black Track 5.9 and the ultra classic Crimson Chrysalis 5.8+). There are also a few famous climbers with limb loss, and good documentary films of their adventures. This article is to provide a basic introduction to prosthesis so you be in the know the next time you meet one of those badasses in the wild.

What is a prosthesis?

A prosthesis or artificial limb, is a device to replace the lost limb segment for someone with limb loss or born with limb difference. Depending on what is lost, a prosthesis varies in length and the number of joints. For example, someone who lost the leg below the knee will need to replace his calf, ankle, and foot; someone with an above-the-knee amputation will also need to have a knee joint. Certified prosthetists help to make these devices.

How does the prosthesis connect to the person?

This is a common question when people see a climber with a prosthesis: “How does the leg stay on?”, “What if the leg falls off?” A key design of any prosthesis is called the “suspension.” It keeps the prosthesis connected to the remaining leg even when the leg is not weighted and dangling in the air. (Note: the remaining leg is sometimes called “stump” but the correct name is “residual limb”.)

There are several different types of suspension design. Some designs use a strong suction and vacuum pump. Others wear a tight sock on their residual limb that has a pin at the end. The pin is then inserted into the prosthesis (Figure 1).

Does it hurt to wear a prosthesis when walking or climbing?

Our feet are tough, with thick skin and fat pads. They are designed to take a beating. The rest of the leg is not as tough and can easily bruise or blister when subjected to pressure and friction, so prosthesis users do need to protect their residual limb. Just about every amputee wears a sock on their residual limb, and the inside of the sock is usually lined with silicone gel to make it really soft and comfortable. The gel also helps to maintain a firm and non-sliding contact so the wearer does not get blisters. The leg is then pushed into a bucket made of tough plastic (called socket) so it is fairly stable (Figure 2). Just like a pair of ill-fitted shoes, if the shape of the socket is off, it can feel very uncomfortable. Therefore, the socket is custom-made for each person.

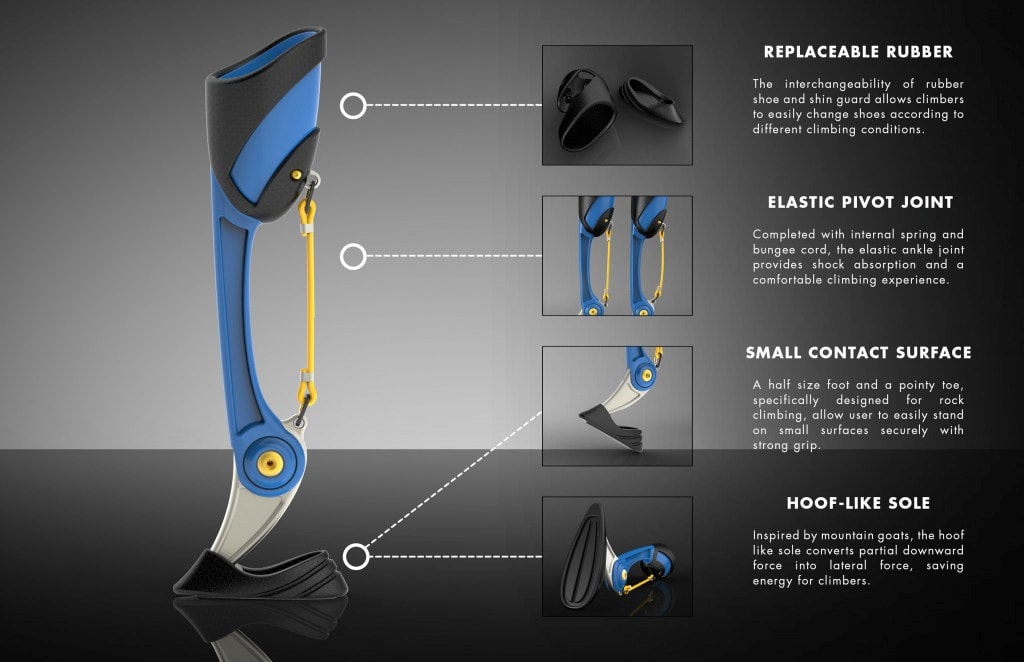

But why not take advantage of the fact that your foot is now interchangeable? Why not wear something smaller so you can easily stand on tiny edges? The famous inventor/double amputee climber Hugh Herr made the “hatchet foot” to stand in really thin crack.

A crampon can be attached instead of a foot for ice climbing.

There are several designer-made prostheses on the market, such as the Kai Lin leg used by Arcteryx athlete Craig DeMartino (Figure 4, the Kai Lin leg). Evolv also worked with a prosthetic company to come up with an affordable foot and climbing shoe (Figure 5, the El Dorado foot). Because the prosthetic foot is simple in design and can be easily swapped, they are not that expensive (in the range of a few hundred dollars).

Handy amputee climbers often make their own foot. The bottom line is that there is no standard design on what is the best climbing prosthesis, just like climbing shoes! Most amputees also don’t mind talking about their prosthesis just like us non-amputees talking about shoes and gear.

What are the biggest challenges of climbing with a leg prosthesis?

I am not an amputee myself but I do work with many amputees specifically rehabilitation after amputation - so I am making an educated guess here. The first challenge is that the ankle and toes cannot move. If you put weight on a prosthesis, the ankle/foot may flex a bit, but it is not possible to point your toes in different directions. So the footwork will be limited in this aspect. It is also difficult for an amputee climber to feel the rock. We rely heavily on the sensation of the feet to guide foot placements in climbing, and footwork is tricky when that sensory information is not available. So, amputee climbers may need to rely on their vision more.

Climbing is more challenging for those who have higher levels of amputation such as above-the-knee or higher. Because the current technology is not yet at the Ironman exoskeleton level (which moves to the will of the user.) Anyone with above-the-knee or higher level amputation would have lost control of 2 important joints (knee and ankle). Certain moves like balancing only on the prosthetic leg, high step or drop knee that requires delicate control of the knee will be very tough for someone wearing a prosthesis with an artificial knee.

Imagine climbing while wearing a knee brace that keep the knee unbendable! That is why when climbing steep boulder problems where the leg is not as important, some amputee climbers take their prosthesis off.

To see a good example, you can watch this video

Although there are numerous challenges and adjustments to living and climbing after an amputation, ultimately, climbing with a prosthesis (or an amputation without a prosthesis) is harder, but certainly not impossible. Amputees have climbed 5.13, V10, El Capitan in a day, and the Everest!

Reference

1. Ziegler-Graham K, MacKenzie EJ, Ephraim PL, Travison TG, Brookmeyer R. Estimating the prevalence of limb loss in the United States: 2005 to 2050. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation. 2008;89(3):422-429.