Hey Matt, thanks so much for taking the time to share with Common Climber! We love to get to know the people behind the photos.

You live in the Portland, OR area. What do you do there?

I help run Stoneworks Climbing Gym with my dad, Robert. It’s one of the last “mom and pop” gyms around and has a really amazing community. We’ve seen three generations of climbers pass through and when I sit down and think about the idea of that climbing lineage (of someone who brought their kids in to climb and now their kids have kids who are climbing) it’s really special. I get a lot of satisfaction and joy from being there, especially coaching the youth team and setting routes.

I also write for Nike Sportswear, creating copy for their lifestyle shoes. It’s a fun environment and my office is at Nike World Headquarters, which allows me to take “creative breaks” and wander around the beautiful campus, its gardens, lake and forests.

When I’m not at Stonework or Nike, I write poetry and essays. Some of these have been published, others seem to be consistently in editing phase and a few I get to share with audiences at readings. Recently, I was invited to Brooklyn to read at the new Brooklyn library

You live in the Portland, OR area. What do you do there?

I help run Stoneworks Climbing Gym with my dad, Robert. It’s one of the last “mom and pop” gyms around and has a really amazing community. We’ve seen three generations of climbers pass through and when I sit down and think about the idea of that climbing lineage (of someone who brought their kids in to climb and now their kids have kids who are climbing) it’s really special. I get a lot of satisfaction and joy from being there, especially coaching the youth team and setting routes.

I also write for Nike Sportswear, creating copy for their lifestyle shoes. It’s a fun environment and my office is at Nike World Headquarters, which allows me to take “creative breaks” and wander around the beautiful campus, its gardens, lake and forests.

When I’m not at Stonework or Nike, I write poetry and essays. Some of these have been published, others seem to be consistently in editing phase and a few I get to share with audiences at readings. Recently, I was invited to Brooklyn to read at the new Brooklyn library

|

How long have you been climbing and what are your favorite types of climbing and why?

I have been climbing for 26 years and dabbled in all areas of climbing. When I was younger, I really loved bouldering and competition climbing. Now, I find myself primarily sport, trad and big wall free climbing. I’ve done some mountaineering too, but I get super cold and decided that shivering and getting the screaming barfies isn’t too appealing (though I still sometimes somehow find myself on top of mountains). Mainly, I sport and trad climb. I love it, but I also do it with the knowledge that it will help my big wall climbing. When I was in my twenties (I’m 35), I went to Yosemite to try and free climb the Salathe Wall ground up with a couple friends. It didn’t go very well and we had an epic, but it lit a fire in me that still persists. I went on to eventually free climb El Cap and have climbed the wall via four routes and stood on the top ten times. I’ve also climbed Logical Progression on El Gigante, Cruz Del Sur and The Regular Route on La Esfinge, and numerous other walls in Washington, Wyoming and Canada. You do big wall climbing. What experience do you get out of big wall climbing? How did you break into that type of climbing? Well, I was always drawn to the type of climber that went after big walls: Lynn Hill, Alex Huber, Yuji Hirayama, Todd Skinner, Jim Bridwell – I even had a poster of Todd Skinner and Paul Piana when they freed the Salathe in 1988 and of Lynn Hill on the Nose in my bedroom. The pictures of these climbers were wild and the landscapes so huge that I felt something mysterious and profound when I looked at them. As a kid, it seemed like these climbers were freer and that each lived a life of amazing adventure and that was alluring. So I think the first reason I got into big wall climbing was because I wanted to emulate them. |

Then, after I experienced my first wall – the Zodiac at age 18 – I was so filled with fear and exhaustion and bewilderment I wasn’t sure if it was for me. But on day three I had a kind of epiphany. Adventure, yes. Freedom, yes. But also, the capacity to take in something bigger than ourselves—life performed on a macro and micro levels simultaneously.

As a teenager, this feeling was incredible, and it continues to be; to deal with the unknown, the fear, the pain and everything else that is symbolic of life through a very condensed time frame. To hold ancient ribbons of lava and exfoliating flakes on Half Dome; to see the chatter markings of glaciers that disappeared thousands of years ago; to see a tiny succulent blooming in a crack—astonishing.

So at 18, I found myself sitting on Peanut Ledge on the Zodiac, pretty close to the summit, having the feeling of time moving like a snail—the wind slowly pulled our ropes perpendicular to the wall, huge trees swayed far below, the rock face of Cathedral was silent and still as shadow and sunlight grew and shrank across it. I stared over Yosemite Valley. My friend Laban and I had no real idea what we were doing; Dave Turner and Chongo had let us borrow gear and quickly showed us the basics, but we hardly knew anything. I mean, we barely had our licenses, we didn’t have girlfriends, yet there we were nearing the summit of El Cap. We’d fixed a broken portaledge and overcome sickness. We’d also done the whole route clean. It was the strange simultaneous feeling of being small and insignificant alongside the feeling of wonder and being fortunate.

As a teenager, this feeling was incredible, and it continues to be; to deal with the unknown, the fear, the pain and everything else that is symbolic of life through a very condensed time frame. To hold ancient ribbons of lava and exfoliating flakes on Half Dome; to see the chatter markings of glaciers that disappeared thousands of years ago; to see a tiny succulent blooming in a crack—astonishing.

So at 18, I found myself sitting on Peanut Ledge on the Zodiac, pretty close to the summit, having the feeling of time moving like a snail—the wind slowly pulled our ropes perpendicular to the wall, huge trees swayed far below, the rock face of Cathedral was silent and still as shadow and sunlight grew and shrank across it. I stared over Yosemite Valley. My friend Laban and I had no real idea what we were doing; Dave Turner and Chongo had let us borrow gear and quickly showed us the basics, but we hardly knew anything. I mean, we barely had our licenses, we didn’t have girlfriends, yet there we were nearing the summit of El Cap. We’d fixed a broken portaledge and overcome sickness. We’d also done the whole route clean. It was the strange simultaneous feeling of being small and insignificant alongside the feeling of wonder and being fortunate.

|

You also enjoy photography and writing poetry. Tell us about that.

My parents bought me my first camera when I was 16, a Nikon FM10, and a book of Ansel Adams photographs. Photography was actually my first passion before writing, and I took my camera on the road when I was 17, traveling alone for three months around the West. I found the process of taking photographs to be extremely cathartic and similar to the experience I later found on Peanut Ledge—of finding that strange generative emptiness. On the trip, I would get lost down old dirt roads in Nevada or Colorado and pull off, waiting for hours. I’d watch light change with clouds, watch animals graze against stark backdrops and become mesmerized by wind in grass. Then, when I felt right, I would set up my own still life and freeze the moment forever with my camera. In photography I found memory, thought, and my subconscious coming together—a moment lost in time, but suddenly reverified. When I look into a vast landscape it is no different than beginning a poem or a climb—I feel small, as if I am beginning to move into non-existence. But then slowly the vastness shrinks. I begin to see individual things, calling them what they are: mountains; clouds; flowers, quartz. I am filled with beginner’s mind. Then, I enter thoughts and memories, traveling through time, envisioning people I love and finding what is valuable to me—what’s worth the risk of living. Poetry is the gateway between my thoughts, the world, and others. When I began writing, I found something that was more succinct for my self-expression than photography. It was more daunting too—where a photo never emerges from a blank canvas, the poem (or any writing) is born from true emptiness. The blank page. For me, writing become synonymous with climbing, especially onsight and ground up climbing. You create something from nothing and it can be the most open, spontaneous and honest feeling. |

Do you have a poem about big wall climbing you’d be willing to share?

This is one I wrote a few years back. It began from a prompt that used the quintessential question, why climb.

This is one I wrote a few years back. It began from a prompt that used the quintessential question, why climb.

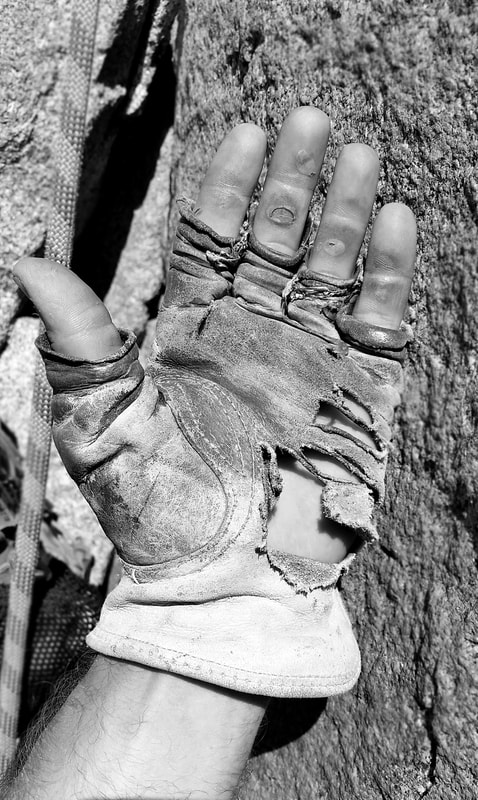

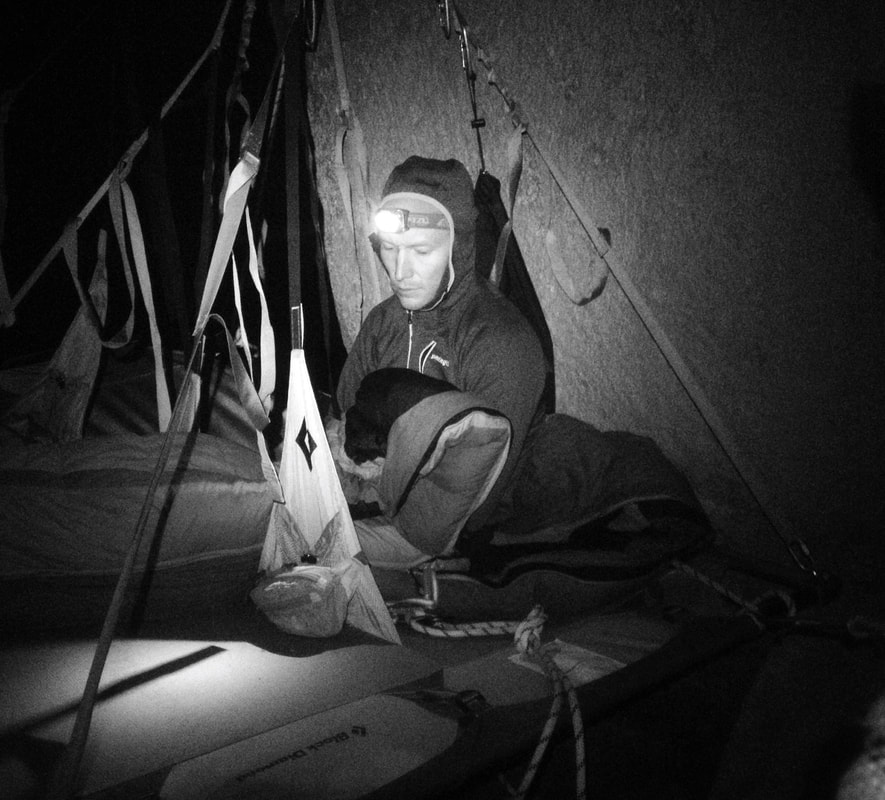

Teacher For our Big Wall edition of Common Climber you are sharing some photos with us. Tell us about these images.

These images are descriptions of life on the wall. I try to get them to show the clutter, the fear, the uncertainty, the beauty and the madness. Simple tasks like cooking or sleeping or setting up camp become transformed into something very intimate and so incredibly exhausting that there’s a strange tranquility once the spoon is in the mouth or the head finally resting on the puffy jacket. Hopefully, when someone looks at them, they see big wall climbing—the dedication big wall climbing takes and in big wall climbing’s ability to freeze and hover a magnifying glass over a brief moment in time. Is there anything you’d love for the Common Climber audience to know? Climbing is at a crossroads and it is our responsibility to move forward in a way that cares for and respects the areas we climb while bringing that same respect to each member of the climbing community and also to those who don’t climb. If you’re going to climb, take the time to read about the places you visit, learn about the flora and fauna, educate yourself on the indigenous people(s) whose land you’re visiting and don’t use social media to post about conquering a route or this or that send but instead use it to share about something spectacular about nature or about the individuals you meet along the way. |

===

Matt Spohn is a poet, essayist, and explorer. He received his MFA in creative writing from Pacific University and has been published in Alpinist, Climbing, Rock & Ice and more. He is the recipient of a 2018 RACC (Regional Arts and Culture Council) grant and is a staff writer for Nike Sportswear. Matt has free climbed El Capitan, climbed on five continents, and established First Ascents throughout the US. He lives in Portland, Oregon with his wife, Michelle, and their Chihuahuas Zoozoo and Cashew.