(Cover by Daga Dygas of Imschatten.photo: Sunrise over a cemetery in Ukraine with the Project H.O.P.E. van. This is a location unlikely to be hit by a Russian attack.)

It was going to be the first time in the mountains in 2022. Erik sat in his fully-packed van with a friend, enjoying their time together before he set off towards the Alps. The plan was to do a winter ascent of Zugspitze in the Wetterstein range - the highest peak in Germany.

It wasn’t long after noon when they learned Ukraine had been attacked by Russian forces - the inhabitants of Ukraine waking to fire and explosions.

It wasn’t long after noon when they learned Ukraine had been attacked by Russian forces - the inhabitants of Ukraine waking to fire and explosions.

A destroyed block of �flats in the very northern part of Kharkiv. Unfortunately, such a sight is quite common in that area. This block is likely almost empty. There aren’t many people in this part of the city now, but some have stayed - like Anton who took us there to show his district and share its story. Anton’s family left but he stayed because he felt obligated as a member of a local council.

Erik and his friend were in his home - a van - in Germany, near Erik’s hometown of Landau in der Pfalz, not far from the French border, and well over 1100 miles from Kiev. The friends, who were surrounded by the safety of the van and distance, sat, trying to process the news.

Information was scarce, but one thing was clear: a war had begun in Europe. Erik didn’t know how or what, but he did know this: abandon the mountaineering trip and head for the Polish-Ukrainian border instead. Never before had he been so far east in Europe.

Erik shared his plans on social media and received support from many of his friends and followers. The day after the war began, Erik shopped in Berlin for food, power banks, and basic provisions. The money came from his spontaneous supporters, as well as from his private pocket. He packed the goods into Sam-the-Van and continued the drive east.

At the border in Przemyśl, Poland, together with soldiers and other volunteers, Erik put up the first tents for the refugees.

A few days later, at the beginning of March, Erik decided to enter Ukraine and evacuate people that contacted him. Big humanitarian organizations were at the border as well, but they kept hesitating, unwilling to enter Ukraine. Erik entered.

He went to Lviv and evacuated a couple - a Swiss man and a Ukrainian woman. The couple had come to Lviv from Kiev and were looking for a way to escape the war-engulfed country. Ukraine was in a state of panic; the people didn’t know how to behave in the face of an armed attack.

Information was scarce, but one thing was clear: a war had begun in Europe. Erik didn’t know how or what, but he did know this: abandon the mountaineering trip and head for the Polish-Ukrainian border instead. Never before had he been so far east in Europe.

Erik shared his plans on social media and received support from many of his friends and followers. The day after the war began, Erik shopped in Berlin for food, power banks, and basic provisions. The money came from his spontaneous supporters, as well as from his private pocket. He packed the goods into Sam-the-Van and continued the drive east.

At the border in Przemyśl, Poland, together with soldiers and other volunteers, Erik put up the first tents for the refugees.

A few days later, at the beginning of March, Erik decided to enter Ukraine and evacuate people that contacted him. Big humanitarian organizations were at the border as well, but they kept hesitating, unwilling to enter Ukraine. Erik entered.

He went to Lviv and evacuated a couple - a Swiss man and a Ukrainian woman. The couple had come to Lviv from Kiev and were looking for a way to escape the war-engulfed country. Ukraine was in a state of panic; the people didn’t know how to behave in the face of an armed attack.

|

Erik saw many civilians out in the streets, trying to support the military by guarding the traffic - sometimes complicating issues because of their lack of training.

The queues on the main border crossings were huge and the road through the forest and villages tiring. Once they entered Poland, the rescued couple didn't let Erik take a break. They insisted on going as far away as possible from the horrors they left behind. Erik drove about 12-hours before they reached the couple's destination in Germany. After dropping off the couple, Erik rested then turned back around to Przemyśl and over the border. Since then, Erik has visited Ukraine more than a dozen times.

During one of his early trips, he got a call from his work, asking: When can he return? He had accepted a new teaching position, one he was excited for, but he informed them he won’t be returning any time soon. Instead, Erik became the founder and leader of a non-profit called H.O.P.E. (Humanitarian Operations, Provisions, and Essentials). Because Erik is a climber, as are most of his followers, H.O.P.E. operates largely in the climbing community. Erik managed to reach people like Alex Megos who agreed to use their (much bigger) platform to bring more attention to Erik’s efforts. I learned about Erik’s history during our drive towards the Polish-Ukrainian border in May 2022. |

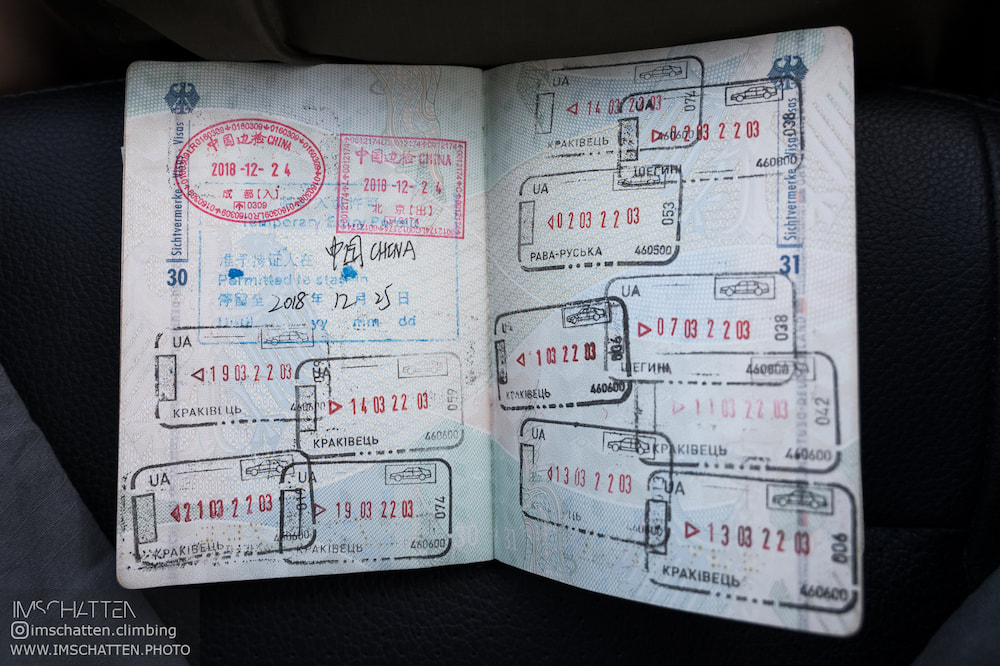

The border crossing stamps in Erik's passport. The repeating rectangular ones are Ukraine entry and exit stamps. There are even more on the following pages. Before February 2022 he'd never travelled to eastern Europe. All of these stamps have been collected between the war outbreak and the aid trip I join him on.

|

After a few unexpected changes in the team, we entered Ukraine as a group of three: Erik as the leader; Daniel - a student inspired by Erik who wanted to do something meaningful before taking his exams; and, myself - Daga the photographer with the desire to help and tell the story.

The aims were to bring medical provisions to Kharkiv, see how the refugees from Dnipro on the eastern side of the country were doing, find out who needs help and assist, and, plan next-step actions for H.O.P.E.

In the western part of the country we saw signs of war sprinkled amongst normal life - ongoing construction work and road blocks, cinema posters, and war related ones. A lot of people were on bikes.

The aims were to bring medical provisions to Kharkiv, see how the refugees from Dnipro on the eastern side of the country were doing, find out who needs help and assist, and, plan next-step actions for H.O.P.E.

In the western part of the country we saw signs of war sprinkled amongst normal life - ongoing construction work and road blocks, cinema posters, and war related ones. A lot of people were on bikes.

At first, I thought bikes were their preferred way to travel short distances; later I learned the truth - the country is struggling for fuel. There’s almost no fuel to be purchased at most of the petrol stations we pass. And if there is any, the queues are enormous.

Back in Poland, we spent what must have been two hours at a petrol station, filling up countless canisters with diesel and stashing them in the cars. I appreciated Erik’s thoughtfulness. Sure, it was important that we got where we needed to be and then back again; but Erik didn't want to put even more strain on a nearly crumbling system by buying deficit goods.

We drove on - much of it filled with long hours of talking and observations. We had many kilometers to go before reaching the cities we needed to visit.

The conversation naturally flowed to climbing; both Erik and I are climbers. We couldn't help but find analogies between this journey and our sport, seeing qualities we developed at the crag that applied so well in other situations: the preparation, be it filling up canisters or packing the right rack; the ability to deal with pressure, on a sketchy runout or when lights go out when you’re about to cross a bridge at night in a war torn country; the open mind, which doesn’t need to follow a precise plan, but rather sees the targets and reaches them - adapting to the circumstances and putting every effort into getting the best you can out of them.

Back in Poland, we spent what must have been two hours at a petrol station, filling up countless canisters with diesel and stashing them in the cars. I appreciated Erik’s thoughtfulness. Sure, it was important that we got where we needed to be and then back again; but Erik didn't want to put even more strain on a nearly crumbling system by buying deficit goods.

We drove on - much of it filled with long hours of talking and observations. We had many kilometers to go before reaching the cities we needed to visit.

The conversation naturally flowed to climbing; both Erik and I are climbers. We couldn't help but find analogies between this journey and our sport, seeing qualities we developed at the crag that applied so well in other situations: the preparation, be it filling up canisters or packing the right rack; the ability to deal with pressure, on a sketchy runout or when lights go out when you’re about to cross a bridge at night in a war torn country; the open mind, which doesn’t need to follow a precise plan, but rather sees the targets and reaches them - adapting to the circumstances and putting every effort into getting the best you can out of them.

Click on the above photos to enlarge and see the caption: Photo Credit: Daga Dygas, Instagram: @imschatten.climbing

Listening to Erik talk, you know he is the right person for the job: he has a keen eye and doesn’t wait to be asked for help - freely offering support whenever he spots a chance to do something for the people on his path through the attacked country. Erik found his role - bringing provisions into Ukraine and taking people out of particularly dangerous areas.

Perhaps most importantly though, Erik brings with him more than just physical things. He brings the human warmth we all know from the crag, sharing friendly smiles and hugs. And, he brings hope - a person from outside of the conflict, who could have stayed safely at home, yet keeps returning to help those affected by the war.

Perhaps most importantly though, Erik brings with him more than just physical things. He brings the human warmth we all know from the crag, sharing friendly smiles and hugs. And, he brings hope - a person from outside of the conflict, who could have stayed safely at home, yet keeps returning to help those affected by the war.

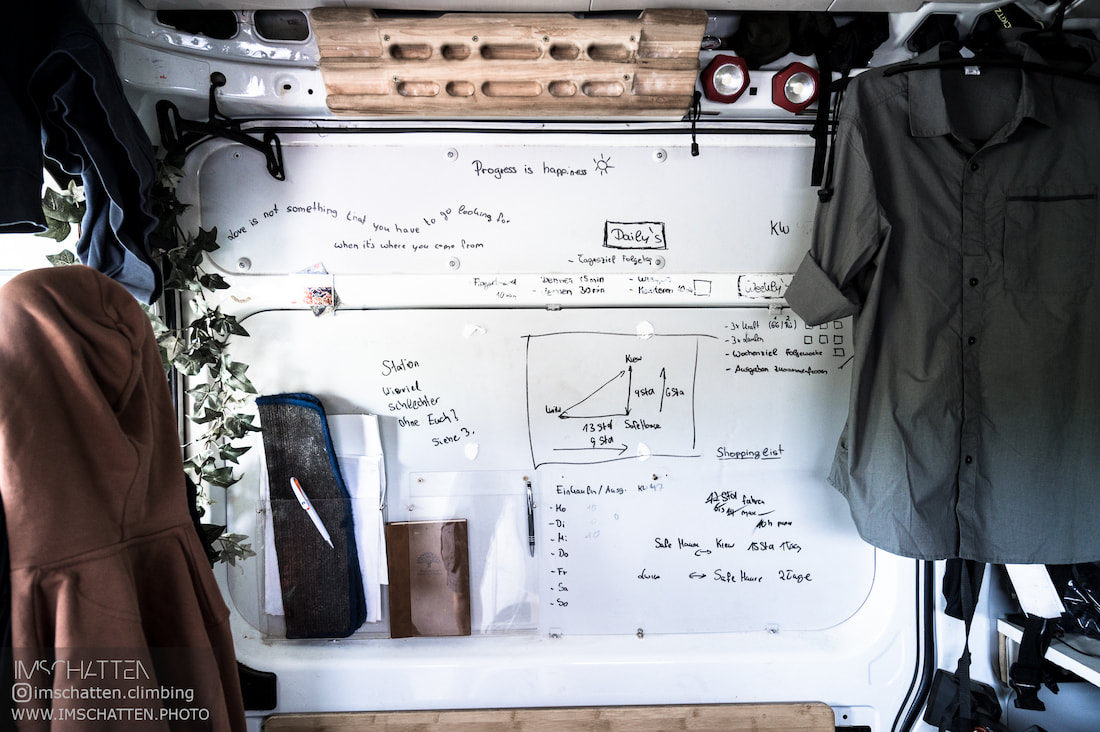

The door of Erik's van: plans for the evacuation of Ukrainians, or a wider spectrum of a whole humanitarian aid trip. I photographed this door on the very day we met. I can envision Erik drawing these, with his omnipresent headset, going through many calls and messages, somewhat chaotic but with a clear target - to help as much as possible.

SLIDE PHOTO SERIES: Photo Credit: Daga Dygas, Instagram: @imschatten.climbing

|

And so two climbers spent a couple of days in one car, driving together over 2700 miles, seeing things many fortunate others will never have to see, but millions have been forced to live through - and not climbing a single time.

Except at the end. When we arrived back in the German Frankenjura, the climbing area near where I live, I told Erik to stop at a crag (one I don’t even like much) and hop onto a traverse. We were exhausted, but Erik deserved to touch rock. It had been too long for him and the sharp, cold stone would certainly be invigorating. It even inspired Daniel, who had not climbed before, to try climbing when he returned back to his home. Erik’s climbing shoes probably still hang right next to the entrance to his van, hoping to be used soon. But for now, this climber still barely climbs. He sacrifices his fitness, and almost all of his time, to those who urgently need support. |

H.O.P.E.

|