They open the gates at Camp Long at eight o’clock sharp. Today, I’m there at 8:05 a.m. to get in a morning bouldering session on Schurman Rock before work.

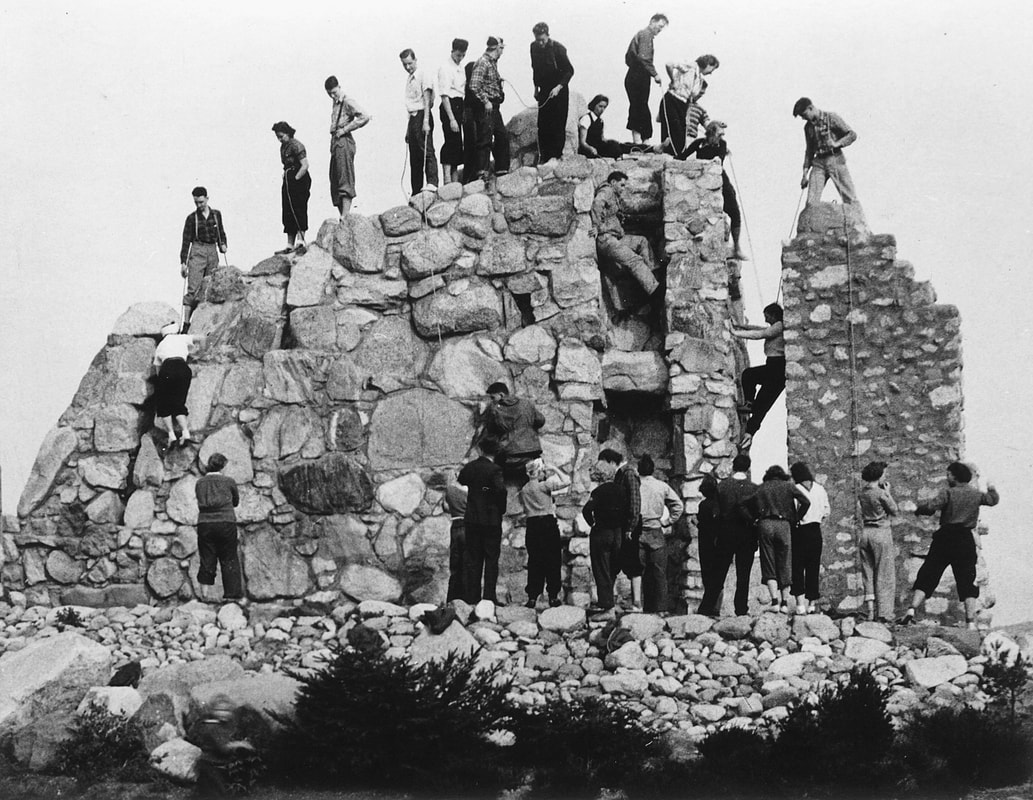

Completed in 1939, Schurman Rock is the oldest known purpose-built artificial climbing wall in the world. Designed by Clark Schurman, a scout leader and climbing guide, and built stone-by-stone under his careful supervision by Civilian Conservation Corps workers, the rock has stood for more than eighty years on a wooded hilltop in a corner of Camp Long, a 68-acre park that many Seattle residents don’t know is there.

Originally called Monitor Rock but later renamed, Schurman Rock was designed to teach mountaineering skills to Boy Scouts and other youth groups, and young climbers including Fred Beckey and Jim and Lou Whittaker learned to climb here, but standing over 20 feet tall and 100 feet around, its utility as a training ground for grown-up climbers was not overlooked by the Mountaineers, who taught basic climbing skills here for decades.

Completed in 1939, Schurman Rock is the oldest known purpose-built artificial climbing wall in the world. Designed by Clark Schurman, a scout leader and climbing guide, and built stone-by-stone under his careful supervision by Civilian Conservation Corps workers, the rock has stood for more than eighty years on a wooded hilltop in a corner of Camp Long, a 68-acre park that many Seattle residents don’t know is there.

Originally called Monitor Rock but later renamed, Schurman Rock was designed to teach mountaineering skills to Boy Scouts and other youth groups, and young climbers including Fred Beckey and Jim and Lou Whittaker learned to climb here, but standing over 20 feet tall and 100 feet around, its utility as a training ground for grown-up climbers was not overlooked by the Mountaineers, who taught basic climbing skills here for decades.

I climbed on Schurman Rock as a teenager but stopped going there after the University of Washington practice rock—a bigger, more-modern artificial wall—was built in 1976. A decade later, the first indoor climbing gym was opened in Seattle, and before long even the U.W. rock was mostly abandoned. When the Mountaineers built their own outdoor climbing wall in 2008, they pretty much stopped using Schurman Rock. It was still there, though, a giant man-made boulder hidden in the woods, waiting to be rediscovered.

When I moved to West Seattle several years ago, I stopped by Camp Long and there it was, a little mossy, but still somewhere close to home to get in a little bouldering. Before long, I was coming once a week, then twice, then pretty much every day it wasn’t raining. Like today, a nice morning, cool, crisp, and ripe with possibility.

Most days, I have Schurman Rock all to myself, and that’s what I’m hoping for this morning. Unless there are people staying in the cabins they rent for overnight camping, there’s nobody else in the park except an occasional dog walker or retired couple out for an early stroll, who might say hello as they pass, or say nothing.

Even when there are campers, they are busy with morning rituals: dressing, eating breakfast, packing to go. There’s almost never anybody else climbing on the rock this early, and it seems quiet this morning as I walk from the parking lot to the rock.

I hear a few voices at one of the cabins, kids laughing somewhere in the distance.

A brown rabbit is nibbling grass beside the parking lot, ears up, keeping a wary eye on me. A squirrel hops down the trail and climbs the back side of a Douglas fir tree. A jay scolds me from a hemlock limb farther down the trail. A wren darts into the safety of the salal bushes, tail flicking as I pass. Some mornings I see an osprey flying overhead, a fish grasped in its talons; a bald eagle soaring high overhead or perched in a tall tree; a barred owl floating silently from tree to tree. With all the wildlife, I come out onto the big grassy field expecting to see Bambi frolicking among the clover.

It’s that kind of morning: calm, serene, just me and the fauna, perfect for a little climbing on the rock.

And then it isn’t.

As I come across the field, I see a half-dozen kids cavorting on top of Schurman Rock and hear the familiar crunching of footsteps on gravel below accompanied by unrestrained laughter, which means more kids are playing around the base of the rock.

If it was the weekend, it would mean a group of kids had commandeered the rock and might be having any number of misadventures on it: races to the top, stick fights, trying to push each other off, what have you.

But it’s a weekday, which usually means a youth group is in the park for a climbing session.

Either way, it’s an annoyance.

At best, I’m going to have to share the rock with a bunch of unruly kids. At worst, the rock will be closed while the class is in session.

Still, I’ve driven all this way, and am determined to get in a bouldering session, kids or no kids.

“Please don’t throw gravel,” I tell them politely while I’m changing into my rock shoes. “There are other people here.”

“Yeah,” says one of the girls, who acts like she’s in charge.

The boys stop for a minute but are at it again as soon as I am out of sight.

But it’s a weekday, which usually means a youth group is in the park for a climbing session.

Either way, it’s an annoyance.

At best, I’m going to have to share the rock with a bunch of unruly kids. At worst, the rock will be closed while the class is in session.

Still, I’ve driven all this way, and am determined to get in a bouldering session, kids or no kids.

“Please don’t throw gravel,” I tell them politely while I’m changing into my rock shoes. “There are other people here.”

“Yeah,” says one of the girls, who acts like she’s in charge.

The boys stop for a minute but are at it again as soon as I am out of sight.

“Seriously,” I say as I climb up over the top edge of the rock, startling them. “The gravel’s there for safety reasons, and I don’t appreciate getting hit by rocks while I’m climbing. And you get gravel all over the rock, which makes it unsafe up here. Somebody could slip on the loose rocks and fall off.”

“Yeah, knock it off,” two of the girls tell them in unison.

“Yeah, knock it off,” two of the girls tell them in unison.

|

The three boys begrudgingly knock it off. It’s clear that the anti-rock-throwing sentiment is rising, and they are clearly outnumbered. They scramble down and wander off to do their mischief elsewhere.

“Did you just climb up that wall?” asks a tall girl who’s wearing a Mickey Mouse T-shirt. “I did,” I say. “Aren’t there any adults here with you?” I take a survey of the dozen or so pre-teens scampering around the rock. Girls outnumber the boys three to one now that the troublemakers are gone. “They’re at the cabins,” says another girl, looking at me over the top of her red-framed glasses. “They told us to go play while they cleaned up after breakfast,” explains another girl, who’s sporting black-and-maroon corn rows. “Are you all together then?” “Our school group is camping out here,” she tells me. “We’re from Oregon.” |

I go about my business, climbing laps up and down my usual circuit of boulder problems, getting in my workout, trying to ignore the kids.

A few of them watch me intently as I climb; they pepper me with remarkably intelligent questions:

“Does the chalk help your grip?” (“Can I try some?”)

“Do those shoes make it easier?”

“Do you always climb without a rope?”

“Have you ever climbed El Capitan?”

A few of them watch me intently as I climb; they pepper me with remarkably intelligent questions:

“Does the chalk help your grip?” (“Can I try some?”)

“Do those shoes make it easier?”

“Do you always climb without a rope?”

“Have you ever climbed El Capitan?”

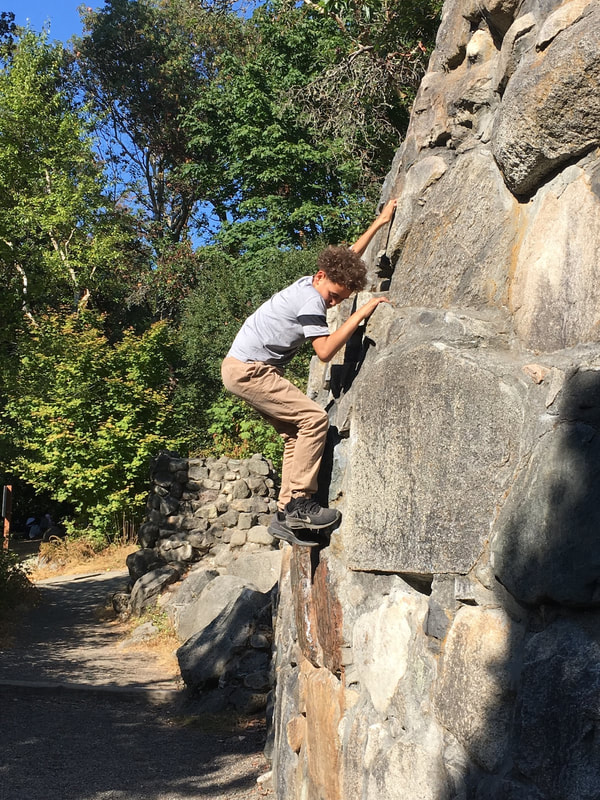

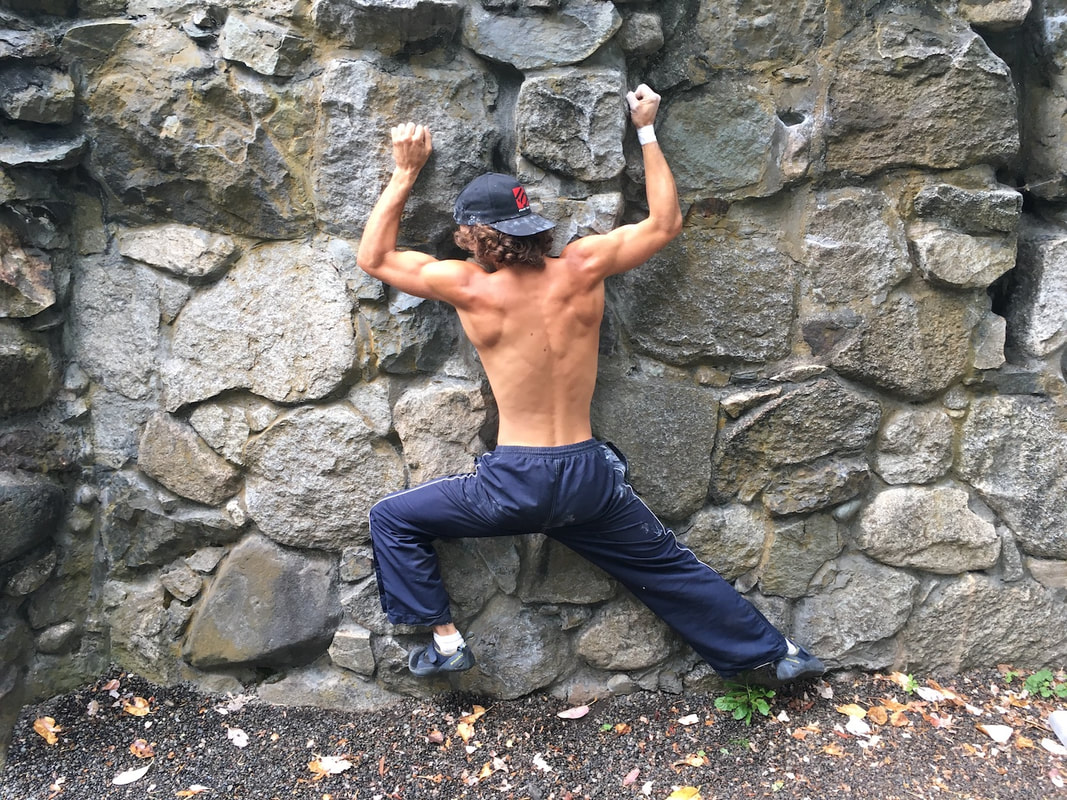

The author, Jeff Smoot, working on a boulder problem amongst the cacophony.

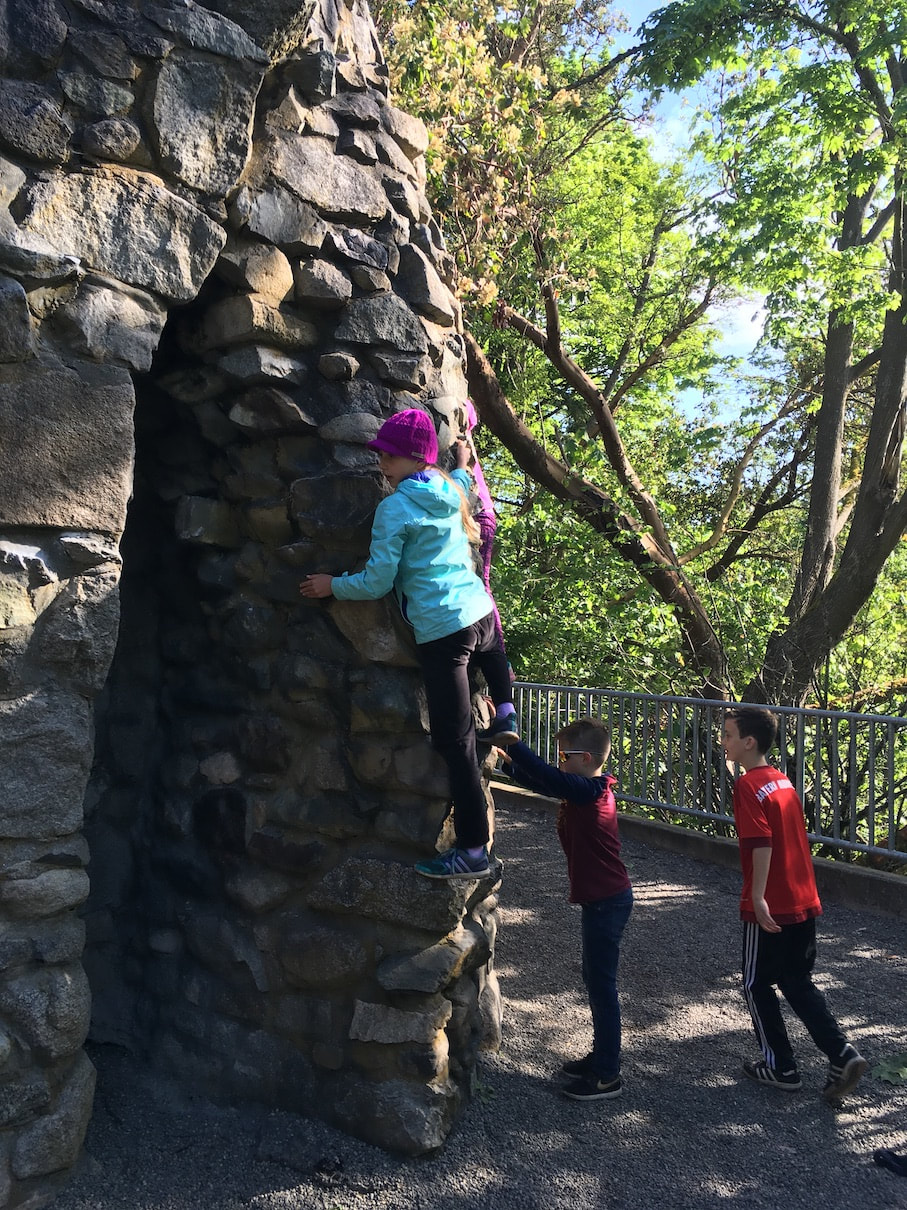

A small group of kids is collectively working out the easiest route up the detached tower and, then, the way down, which involves a three-foot step across from the tower to a ledge on the main rock, fifteen feet off the deck, a scary proposition. A girl in a bright purple pullover has made it to the top first; she contemplates the step-across move but balks at the exposure. A boy in space-cadet sunglasses is coming up right behind her, and a girl wearing a bright pink hat is closing in fast. Meanwhile, another girl wearing a light blue headband is stemming up between the tower and the main wall, attacking the problem directly. She reaches the top and makes the exit move easily. The others, having seen it done, quickly follow her across.

The group reconvenes at the southeast corner of the rock, a stone-studded buttress that’s not quite as steep as the other walls.

The group reconvenes at the southeast corner of the rock, a stone-studded buttress that’s not quite as steep as the other walls.

|

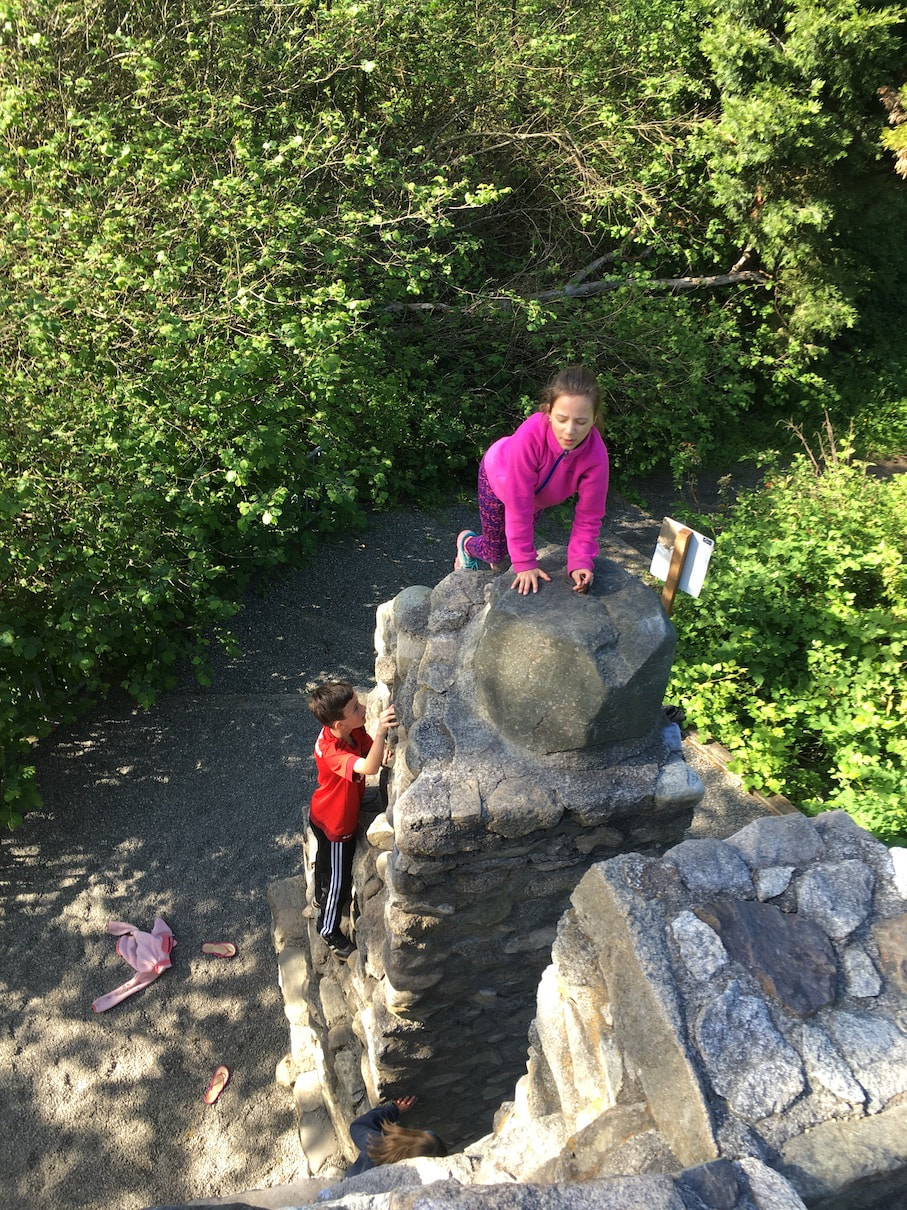

The girls lead the way again, the girl in the pink hat climbing up one side of the buttress, purple pullover girl up the other. The boy in the red shirt (whose name is Steven, I have learned) and the space cadet are right behind them. After a few aborted attempts, they are on top and looking for another route to try.

“What should we climb now?” Steven asks me. “I can’t really tell you what you should climb, you know,” I tell him. “If I do, and you fall and get hurt, your parents will sue me.” “No, they won’t,” he assures me. “Are your parents even here?” I ask. “My mom is,” he says. “Does she know you’re over here climbing on the rock?” “No.” “Hmm,” I say. “Well, some kids seem to manage to climb up the crack on the other side of the rock. I’m not saying you should climb it, just that I’ve seen some kids climb it.” “Thanks!” he says. “Come on you guys!” |

Meanwhile, two of the girls in the group have been quietly working out the moves up the steepest side of the rock. They’ve removed their shoes and socks and are climbing barefoot to get a better grip on the slick holds. They aren’t talking with anybody, not even each other. Each is in her own world, completely focused on climbing the wall.

The girl with the pageboy haircut sees me watching her and almost glares at me, as if I’m interrupting her flow. The other, who has her hair in a ponytail, seems oblivious to my presence. She’s obsessed with finding a route up the steepest part of the wall. She tries one way, then another, grabbing this hold and that, probing for a line of weakness. Finding none, she climbs down and surveys the wall, then tries again.

“If you can get to that big hold to your right, the rest is pretty straightforward,” I suggest while I chalk up between laps.

“Oh,” is all she says. Like I said, she’s all business.

She moves to the right, reaches up to the big hold, repositions her feet, and hangs there momentarily. She’s now on the steepest, blankest part of the wall; except for the big hold she’s latched onto with both hands, there are only a few thin handholds. Still, a big smile comes over her face. She knows she’s won. From here, she can get her feet on a couple of good footholds and make a long reach to a higher hold that is the key to climbing the wall. She grabs it easily, pulls up, and is soon on top.

The other girl works out a different route up the wall. Both bound down the easy ledges and are back for another try. On the other side of the rock, the gang of five is engaged in a mass assault on the crack.

The girl with the pageboy haircut sees me watching her and almost glares at me, as if I’m interrupting her flow. The other, who has her hair in a ponytail, seems oblivious to my presence. She’s obsessed with finding a route up the steepest part of the wall. She tries one way, then another, grabbing this hold and that, probing for a line of weakness. Finding none, she climbs down and surveys the wall, then tries again.

“If you can get to that big hold to your right, the rest is pretty straightforward,” I suggest while I chalk up between laps.

“Oh,” is all she says. Like I said, she’s all business.

She moves to the right, reaches up to the big hold, repositions her feet, and hangs there momentarily. She’s now on the steepest, blankest part of the wall; except for the big hold she’s latched onto with both hands, there are only a few thin handholds. Still, a big smile comes over her face. She knows she’s won. From here, she can get her feet on a couple of good footholds and make a long reach to a higher hold that is the key to climbing the wall. She grabs it easily, pulls up, and is soon on top.

The other girl works out a different route up the wall. Both bound down the easy ledges and are back for another try. On the other side of the rock, the gang of five is engaged in a mass assault on the crack.

That’s when the adults show up.

“Did you know they were here?” I ask a man in his late thirties, the first grown-up on the scene, who is standing there with his arms folded, looking stern yet seemingly amused, proud even. He’s one of the teachers.

“No,” he says. “Have they been causing any trouble?”

“Not at all,” I assure him. “They’ve been very well behaved. I don’t think I’ve ever seen a group of kids on the rock as polite as these kids. They’re really into climbing,” I add. “It’s great that you expose them to this kind of thing.”

Steven walks by and says “Hi, Jeff!” like I’m his new best friend.

He starts climbing the tower again behind purple pullover girl, who is in the lead once more. More adults arrive. They don’t seem quite as amused as the teacher.

“Oh, my gosh,” a woman exclaims upon seeing the kids climbing all over the rock. “What are you doing up there?”

“I’m climbing, Mom,” Steven says cheerfully from the top of the tower.

“That doesn’t look safe,” she says fretfully, almost to herself.

“It’s great that the kids have been left alone to do this,” I tell her, trying to be reassuring. “They’re really an adventuresome bunch. Does their school encourage this sort of thing?”

“Yes,” she says, without a hint of enthusiasm.

“It’s probably better that the parents don’t know what’s going on sometimes.”

“Yeah. It’s making me nervous. I have to bite my tongue.”

“It’s good that nobody’s telling them to get down,” I assure her. “I think it’s important to let kids test their limits. They’ve been pretty safe so far. They’re amazingly self-reliant, and they’re really into it.”

“I can’t watch,” she says, then adds before she walks away, “Steven, you be careful.”

“Okay, Mom,” he says right before he does the step-across move like it’s no big deal.

“Five more minutes,” the teacher announces. He’s feeling the vibe from the parents; it’s time to call them down. “Then come back to the cabins. It’s almost time to leave.”

“Aww,” comes a collective groan from the kids. They each climb the rock one last time, then run to the cabins and they’re gone.

It’s quiet now. And although I had come hoping to have the rock to myself, I kind of miss the company.

Climbing at Schurman Rock

|

Check out the Friends of Schurman Rock group page on Facebook! Share your Schurman Rock experiences and photos!