2017

I'd moved to Yosemite. I didn't know for how long, but I was staying. At that point in time I had nothing tethering me to any specific point in the world. I was 21 and borrowed 400 dollars to go coast to coast. My friend Jake came along to split the cost of gas and suddenly we had a trip in our laps we had been threatening to do for seven years.

I skipped graduation and we took off from Boston. A 30-hour push brought us to some afternoon beers in Ogallala, then Denver and Nederland, Colorado.

That night we slept in the front seats of the car and 18 inches of snow fell. The highway was closed at Georgetown, so we wheeled south to Pueblo, Colorado, then west across New Mexico, and finally wheeling into Flagstaff, Arizona, spending the night under a blanket of pines so dense and soft that nothing made a sound.

I left Jake in Las Vegas and roared on alone to California. Mojave and Tehachapi Pass, one of the great mountain passes of America, Bakersfield, Fresno, and Oakhurst. Oakhurst, is one of the gates to the Kingdom.

That evening, I did a poor job shaving in my rearview mirror at one of the pull outs above town, just past El Cid. I had a vague notion that someone at the concessionaire Human Resources office would give a shit, but they didn’t. I moved into a HUFF tent, in Curry Village, the very next afternoon.

Kanyon Lalley was one of the first people I met. We were doing our housekeeper’s training. It was at the Ahwahnee, even though we were going to be working at the lodge, so the training wasn’t actually all that helpful. To impress us, they showed us the suite JFK had stayed in. The truth was, we were pretty impressed. I was chilling on the patio when he approached me with the words every climber in a totally new place wants to hear.

“Do you climb?”

Plans were made, but first we had to work a few shifts at the lodge. It became clear that there were two styles of housekeeping related to speed and thoroughness: fast and light versus slow and heavy. It was necessary to have both types of housekeepers on the staff to ensure not only cleanliness, but also that we got done at a reasonable time each day. Kanyon was the only person who did not seem to fall into either category. There were whispers you would get fired if they caught you not vacuuming a room. Yet frequently, I would go to help him finish his rooms in mid-afternoon and the vacuum would be left derelict, sitting in the linen closet all day. He was irreverent. He didn’t give a fuck. And we became friends.

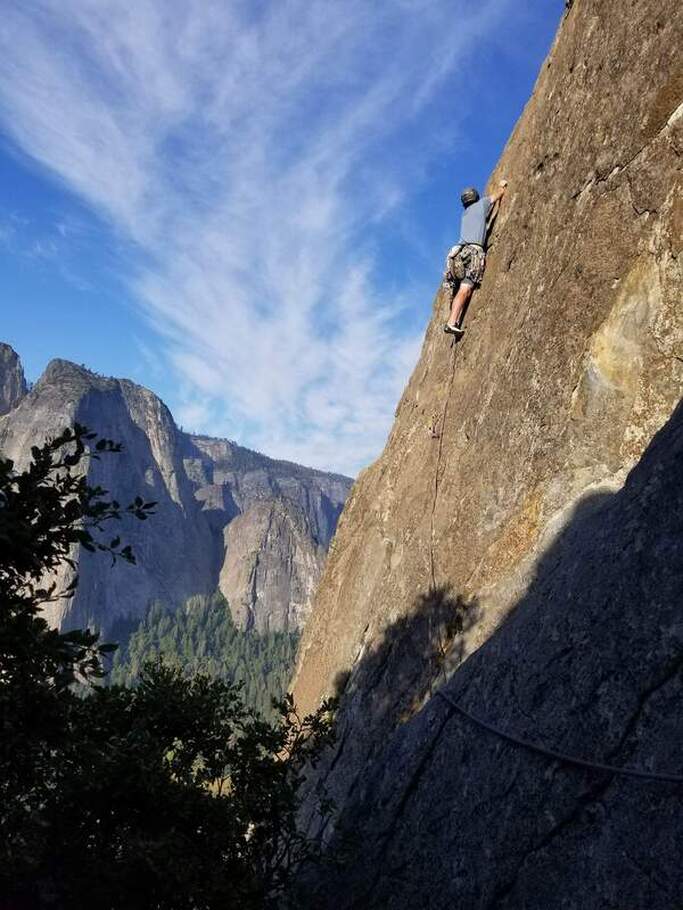

Our first proper valley shitshow was when we were trying to find Braille Book. We strayed too far to the right and accidentally began climbing the steep treacherous gully between middle and higher cathedral rocks. We ended up bailing before even getting to the climb and went over to Sunnyside Bench instead. We made it up the climb, but had no idea how long the walk off was and didn’t bring our shoes.

I'd moved to Yosemite. I didn't know for how long, but I was staying. At that point in time I had nothing tethering me to any specific point in the world. I was 21 and borrowed 400 dollars to go coast to coast. My friend Jake came along to split the cost of gas and suddenly we had a trip in our laps we had been threatening to do for seven years.

I skipped graduation and we took off from Boston. A 30-hour push brought us to some afternoon beers in Ogallala, then Denver and Nederland, Colorado.

That night we slept in the front seats of the car and 18 inches of snow fell. The highway was closed at Georgetown, so we wheeled south to Pueblo, Colorado, then west across New Mexico, and finally wheeling into Flagstaff, Arizona, spending the night under a blanket of pines so dense and soft that nothing made a sound.

I left Jake in Las Vegas and roared on alone to California. Mojave and Tehachapi Pass, one of the great mountain passes of America, Bakersfield, Fresno, and Oakhurst. Oakhurst, is one of the gates to the Kingdom.

That evening, I did a poor job shaving in my rearview mirror at one of the pull outs above town, just past El Cid. I had a vague notion that someone at the concessionaire Human Resources office would give a shit, but they didn’t. I moved into a HUFF tent, in Curry Village, the very next afternoon.

Kanyon Lalley was one of the first people I met. We were doing our housekeeper’s training. It was at the Ahwahnee, even though we were going to be working at the lodge, so the training wasn’t actually all that helpful. To impress us, they showed us the suite JFK had stayed in. The truth was, we were pretty impressed. I was chilling on the patio when he approached me with the words every climber in a totally new place wants to hear.

“Do you climb?”

Plans were made, but first we had to work a few shifts at the lodge. It became clear that there were two styles of housekeeping related to speed and thoroughness: fast and light versus slow and heavy. It was necessary to have both types of housekeepers on the staff to ensure not only cleanliness, but also that we got done at a reasonable time each day. Kanyon was the only person who did not seem to fall into either category. There were whispers you would get fired if they caught you not vacuuming a room. Yet frequently, I would go to help him finish his rooms in mid-afternoon and the vacuum would be left derelict, sitting in the linen closet all day. He was irreverent. He didn’t give a fuck. And we became friends.

Our first proper valley shitshow was when we were trying to find Braille Book. We strayed too far to the right and accidentally began climbing the steep treacherous gully between middle and higher cathedral rocks. We ended up bailing before even getting to the climb and went over to Sunnyside Bench instead. We made it up the climb, but had no idea how long the walk off was and didn’t bring our shoes.

|

The Community Center, long the main gathering spot for employees, was temporarily closed because someone had taken a shit on the floor, word had it. Still, I managed to start meeting a few people, and a circle was starting to form. Rob - my college buddy, Elliot - Kanyon’s friend from back home in South Dakota, and Caroline.

Caroline fell into our crew quickly. She was not a climber yet, but had the climbing spirit and energy. My cell phone broke, and we made the long drive down to Fresno to get it fixed. It would be a while longer before we admitted our love, but it started to grow from the very beginning. Before long, I had moved into her tent. Privately, I had been lonely, or at least alone in my thoughts, for a long time. Our connection felt like a first breath of air after being underwater. The loose, funky crew had become family. We started having some success. East Buttress of Middle Cathedral was our first epic. We climbed as a team of three with not enough water. We didn’t have the experience to know what Grade IV meant yet. We joked at the top “just keep drinking half and you’ll never run out.” But we ran out. Recklessly dehydrated, Rob reported experiencing pulsing hazy vision on the rappels. Higher Cathedral Spire, East Buttress of El Cap, Snake Dike, Central Pillar and Matthes Crest were some proud early sends for our ragged group. We were falling in love with Yosemite, with climbing, and each other. There was a collective spirit. Every waking moment swelled with possibility and potential. I felt as rich as I had in my whole life, even though we didn’t have that much money. You were rich if your beer was full, if you had a few dollars in your pocket, or had plans to go climbing. |

We started thinking we were kinda cool. One day, after climbing, Rob and I sat in gridlocked traffic on southside drive for close to an hour. It was a Saturday in July, and the procession snaked from one end of the valley to the other. We were hungry and dehydrated.

In a moment of youthful exasperation and haste, I muttered “fuck it” and nosed the car into the empty bus lane. We were flying, passing hundreds of cars. People stuck their heads out, yelled, and flipped us off. A few were bold enough to follow. We had almost made it, when we were pulled over by two rangers on bicycles right in front of the chapel and slapped with a nasty fine and verbal beatdown. Still, we made it back to Curry Village in one piece and were laughing about it with friends by nightfall.

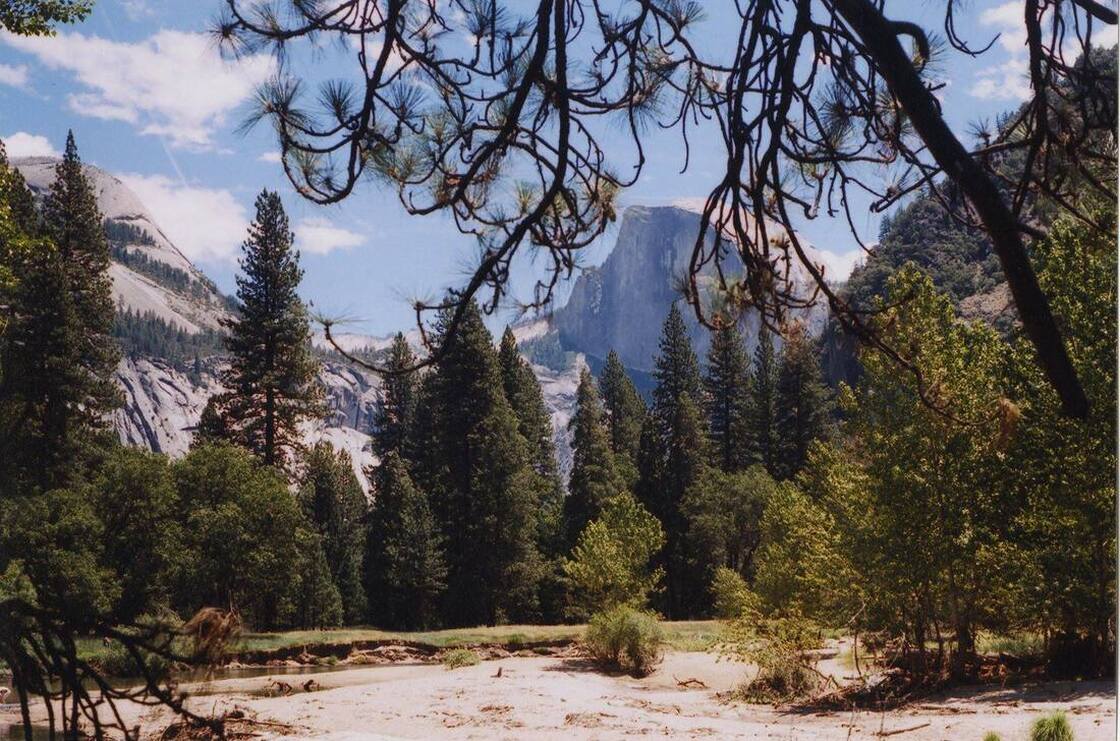

My first summer in Yosemite was ending. Leaves were starting to change. It was time for other adventures, but before I even left the valley I knew in my heart that I had found what I was looking for and that I was going to be here forever.

I left and roamed around the country getting big ideas in my head.

2018

I dropped Rob off at the Greyhound station in Portland, Oregon. It was 10 p.m. on a warm spring night. He was taking the bus all the way to southwest Colorado where he had made his home after leaving the dirtbag circuit. Caroline was back east visiting family. It became clear that there was nothing else to do at that moment except to begin the long drive back to Yosemite. I drove all night through misty southern Oregon and by day was flying in the hot plains of the central valley. I went straight to the lodge and found Kanyon cleaning a hotel room. I helped him fold a few towels. The vacuum sat idly in the linen closet. It had begun again.

We knew we needed to get into Big Wall climbing. Anyone who spends enough time in Yosemite will eventually be drawn by these mysterious, giant, vertical puzzles. I was lined up to clean rooms again - put the Dickies back on, shuffle into the morning sun, stoned, hauling bags of bleach and Lysol around the property. We often found left over beers in the fridges - tourists who were about to get on an airplane. Crack open a cold one, make the bed, don’t forget to clock out for lunch.

It was not without conflict though. I had a college degree from an outdoor program. Some peers from those days were working for Outward Bound, NOLS, working up the AMGA ladder. I was cleaning pubes out of the tub.

When Caroline showed up they put her in temporary housing, which is widely regarded as the shittiest employee housing. Instead, we slept in the forest between stoneman meadow and the river for a little while before getting a spot in Boys Town. Boys Town was next to the tourist tents so it was more low-key than the raucous HUFF. In HUFF, you couldn’t stumble to the bathroom to piss at night without people partying in the tent rows offering you liquor, cigarettes, whatever. In Boys Town you could just piss. We settled into our new quiet neighborhood in the valley and started climbing.

This year, I had also recruited another college buddy to work in the Valley – Justin. For one of our first valley outings we climbed the NEB on Higher Cathedral together. Justin was one of my favorite people to climb with, because he climbed really fast, and we had climbed together in the Winds of Wyoming. We approached the route a little too casually and got semi-thrashed. Still we were nearing the top with plenty of daylight. One pitch from the top, off route, we made an eerie discovery. There was a gear anchor, and a sequence of gear going up the cliff, but no rope and no climbers. It was like they had vanished, yet there were probably 15 nuts and cams left in the wall. Spooked, we grabbed the stuff and topped-out. Later, we could not find any accident reports, mountain project, or super topo posts about it, so we just kept the gear.

I split my share of the gear with Caroline. I had taught her to climb, but she was quickly becoming her own climber. Pushing herself hard into new realms when I wasn’t there. She was also inspired by big climbs, so that summer we climbed the Red Dihedral on the Incredible Hulk car-to car.

There was this rising feeling within me that I needed to start wall climbing. It was hard not to get obsessed. Both Washington’s Column and Half Dome towered over Curry Village, so it was hard not to wonder. You could see Half Dome from the bathroom. I learned to jug and use a fifi hook at the LeConte Boulder after work and in the morning we were off to Washington’s Column.

I was up there with my friends Kanyon and Elliot and we had no idea what the hell we were doing. I jugged with my sleeping bag clipped to my haul loop. At Dinner Ledge we smoked lots of weed, and it was well after dark before I finished racking up, tying in, and casting off into the darkness on the Kor Roof, my first ever aid lead. I was scared out of my mind. Ladders twisted, bounce testing C1, shaking, hoping, praying. We bailed in the shimmering heat early the next afternoon. We didn’t take any pictures because we knew in our hearts we were going to be here forever.

A week later Justin and I hit Washington Column again. We still didn’t really know how to haul, so beginning at 1 a.m. in the night buzz of chirping crickets, we set sail. We accidentally dropped a loaf of bread when halfway up, our only food for the route. But, we continued on, feeling a rare surge of power. At the top we napped in the dirt, climbing the wall in just under 15 hours. We had done our first big wall climb, I couldn’t believe it. We found the bread on the ledge on the way down and ate slowly in the sunset.

|

There was no complacency after the Column. Justin and I teamed up again, climbing both East Buttress [ED. NOTE: Although the East Buttress is on El Capitan, it is not considered by many to be an “El Cap” climb] and Middle Cathedral in a day. I thought it would be a good way to get in shape for Half Dome.

Only a year before both of these climbs had been all day epics. A progression was taking place, and I was beginning to understand the rewards of commitment to the Valley. This was all in the middle of working at the lodge. At lunch we would swim in the Merced in our uniforms, maybe drink some beers we found in a room and talk shit about housekeeping and climbing. Elliot had fallen deep into the speed housekeeping game and we would take desperate risks to get the rooms done faster so we could go out and climb. The competition for fastest hospital corner in the west was fierce. Lunch wasn’t that long, and you would clock back in pretty damn wet. One day at lunch we noticed smoke coming into the valley, up from El Portal. It was the dawn of what was to become the Ferguson Fire, which eventually burned parts of the park and closed it down for several weeks. Still, there was a little time left before all of that, so Justin and I teamed up one more time to climb Half Dome. I drank a beer while we hiked to Mirror Lake for a little courage. The wall looked huge. We felt inexperienced, just two buds going up there and slugging it out. We had decided to haul and bivy on the route, because we didn’t feel confident doing it in a push. We really didn’t feel that confident in general. After bivying near Mirror Lake, we woke up at 3 a.m. and hiked up the death slabs in the dark. We started climbing, and made it to Big Sandy over 17 brawling hours. Squeezing up one of the last chimneys in the dark, I watched a piece fall out below me, but kept it together. |

At this point, we were relying on rote climbing instinct. We pulled onto Big Sandy ledge at exactly midnight, 21 hours out from Mirror Lake.

“It’s getting smokier. ”

“Sure Is.”

In the morning the valley was choked with wildfire smoke. We had a few sips of coffee. We began methodically climbing towards the top. I was pretty drained from the previous day and moved slowly. We both took whippers on the second to last pitch, we had the wrong hook. Eventually I pieced it together without it but it was scary. We were ready to get off the wall.

In an amazing act of friendship, Caroline and Kanyon had secured a permit to hike Half Dome on the very same day, and hiked up a bunch of beers. We topped out way later than we told them we would, so most of the beer had been consumed by the time we finally shambled over the rim. There were a few left though, and we drank and told tales. It had been the hardest climb of my life so far but already I was remembering the hard parts as not that bad. I marveled at the view and at my friends - tipsy and dehydrated on the summit of Half Dome, daylight fading in a sea of wildfire smoke, yet everyone was stoked. Eight miles down, we made it back to Curry a few minutes before the store closed, and went to work at the lodge the next morning.

The fire continued to grow, and it wasn’t long before the park was closed to visitors. There were no beds to be made. It was a sad time. People floated off in different directions and suddenly Caroline and I were all alone at the Mobil in Lee Vining, wondering where to go or what to do. After a few weeks of drifting around, we went up to Portland. Caroline was going to school there and classes were starting up.

I returned to the valley in the fall. I needed to earn some money and also the wall climbing bug was still in me. I was starting to think that I could have a chance at climbing El Cap. During the fire, fear and uncertainty had filled my days. I felt selfish for brooding when two firefighters had died. But, like a moth to a flame, I was back in the Valley.

It didn’t take long to realize that something was missing. My makeshift Yosemite family wasn’t around. The days felt less full. I learned then that the most important ingredient of any experience is the people you share it with. However, just as my circle felt it was shrinking, it started to grow again.

Charlie was a housekeeper, and had a wealth of knowledge and experience on everything from train hopping to the stock market. He had been a dirtbag before ever discovering climbing. He would belay me while I scared myself, trying to make up for what I felt was lost time. One morning, we were looking inside the smoker’s pole at the lodge trying to find long butts to use for a rollie. Our co-worker Dan, saw us and threw four cigarettes at us in disgust.

“You guys know you can buy these right? I know you have a job, we work together.”

Dan was a Yosemite lifer, someone who has worked in the park for years, and despite not being big climbers or hikers, you know they appreciate and respect Yosemite deeply and dig it on the same subconscious level. Dan had slacklines in his yard set up by Dean Potter and had left them up ever since in his memory. It was also during that time Free Solo came out, and I was able to watch it during the Yosemite FaceLift with an auditorium full of monkeys. Psyche was high, and my end date at the lodge was coming up.

Maison was in the valley. We had worked together the year before but now he was lurking in the valley in a vague capacity. He had gone from a relative beginner to a bad-ass wall climber in only a year. We went up to do Lost Arrow Spire, and after a windy night at the base, I called out of my last shift at the lodge at the top of Pitch 2. They must have heard the wind and clanking metal through the phone, but the manager said “OK,” and that was that. We continued on. Some of the only music we had on our phones was Paul Simon’s greatest Hits. It turned out Fifty Ways to Leave Your Lover has a great rhythm for hauling.

Pitch 7 was a three-hour lead. Maison was up there, toiling away on the sunbaked granite in tricky pin scars. The day burned along. It was a completely hanging stance. I sat on the haul bag, but my legs went numb. I moved position and they went numb again. All of a sudden there was doubt, and then fear, followed closely by panic. I ran my fingers along my daisies, the cordelette, even the bolts themselves, my mind racing over the integrity of it all. It was one of those moments when the brain screams “What the fuck am I doing up here?!”

Maison finished the pitch and at the next ledge I expressed my desire to bail. I was met with a prompt “No fucking way!” Considering the pitch he had just finished, I don’t blame him. An hour later, we had made it to 2nd Error Ledge, and were home for the night.

“How bomber is this anchor?” Maison asked, the next day, tip-toeing up the twelfth pitch. Gravel from kitty-litter rock and a phrase you never want to hear from your partner rained down. At the exact same moment, the ripped-out guidebook page serving as our topo, was picked up by the wind and flew out of my open-zippered coat pocket. I watched with a grim resignation as it sailed away into the wind.

Maison reached the next anchor, and we were in the notch, out of the wilderness and on the well-traveled Lost Arrow Tip route. There were fat shiny bolts. Just as I reported to Maison the loss of the topo, a piece of paper fell out of the sky and landed right between our feet. The topo! It had been swirling in the Valley wind for over an hour. We jumped on it like two farmers discovering a bag of gold in their crops. It was an omen, and we pushed to the top, making it at last light, a point in the sky, the world fading to black rapidly around us.

“It’s getting smokier. ”

“Sure Is.”

In the morning the valley was choked with wildfire smoke. We had a few sips of coffee. We began methodically climbing towards the top. I was pretty drained from the previous day and moved slowly. We both took whippers on the second to last pitch, we had the wrong hook. Eventually I pieced it together without it but it was scary. We were ready to get off the wall.

In an amazing act of friendship, Caroline and Kanyon had secured a permit to hike Half Dome on the very same day, and hiked up a bunch of beers. We topped out way later than we told them we would, so most of the beer had been consumed by the time we finally shambled over the rim. There were a few left though, and we drank and told tales. It had been the hardest climb of my life so far but already I was remembering the hard parts as not that bad. I marveled at the view and at my friends - tipsy and dehydrated on the summit of Half Dome, daylight fading in a sea of wildfire smoke, yet everyone was stoked. Eight miles down, we made it back to Curry a few minutes before the store closed, and went to work at the lodge the next morning.

The fire continued to grow, and it wasn’t long before the park was closed to visitors. There were no beds to be made. It was a sad time. People floated off in different directions and suddenly Caroline and I were all alone at the Mobil in Lee Vining, wondering where to go or what to do. After a few weeks of drifting around, we went up to Portland. Caroline was going to school there and classes were starting up.

I returned to the valley in the fall. I needed to earn some money and also the wall climbing bug was still in me. I was starting to think that I could have a chance at climbing El Cap. During the fire, fear and uncertainty had filled my days. I felt selfish for brooding when two firefighters had died. But, like a moth to a flame, I was back in the Valley.

It didn’t take long to realize that something was missing. My makeshift Yosemite family wasn’t around. The days felt less full. I learned then that the most important ingredient of any experience is the people you share it with. However, just as my circle felt it was shrinking, it started to grow again.

Charlie was a housekeeper, and had a wealth of knowledge and experience on everything from train hopping to the stock market. He had been a dirtbag before ever discovering climbing. He would belay me while I scared myself, trying to make up for what I felt was lost time. One morning, we were looking inside the smoker’s pole at the lodge trying to find long butts to use for a rollie. Our co-worker Dan, saw us and threw four cigarettes at us in disgust.

“You guys know you can buy these right? I know you have a job, we work together.”

Dan was a Yosemite lifer, someone who has worked in the park for years, and despite not being big climbers or hikers, you know they appreciate and respect Yosemite deeply and dig it on the same subconscious level. Dan had slacklines in his yard set up by Dean Potter and had left them up ever since in his memory. It was also during that time Free Solo came out, and I was able to watch it during the Yosemite FaceLift with an auditorium full of monkeys. Psyche was high, and my end date at the lodge was coming up.

Maison was in the valley. We had worked together the year before but now he was lurking in the valley in a vague capacity. He had gone from a relative beginner to a bad-ass wall climber in only a year. We went up to do Lost Arrow Spire, and after a windy night at the base, I called out of my last shift at the lodge at the top of Pitch 2. They must have heard the wind and clanking metal through the phone, but the manager said “OK,” and that was that. We continued on. Some of the only music we had on our phones was Paul Simon’s greatest Hits. It turned out Fifty Ways to Leave Your Lover has a great rhythm for hauling.

Pitch 7 was a three-hour lead. Maison was up there, toiling away on the sunbaked granite in tricky pin scars. The day burned along. It was a completely hanging stance. I sat on the haul bag, but my legs went numb. I moved position and they went numb again. All of a sudden there was doubt, and then fear, followed closely by panic. I ran my fingers along my daisies, the cordelette, even the bolts themselves, my mind racing over the integrity of it all. It was one of those moments when the brain screams “What the fuck am I doing up here?!”

Maison finished the pitch and at the next ledge I expressed my desire to bail. I was met with a prompt “No fucking way!” Considering the pitch he had just finished, I don’t blame him. An hour later, we had made it to 2nd Error Ledge, and were home for the night.

“How bomber is this anchor?” Maison asked, the next day, tip-toeing up the twelfth pitch. Gravel from kitty-litter rock and a phrase you never want to hear from your partner rained down. At the exact same moment, the ripped-out guidebook page serving as our topo, was picked up by the wind and flew out of my open-zippered coat pocket. I watched with a grim resignation as it sailed away into the wind.

Maison reached the next anchor, and we were in the notch, out of the wilderness and on the well-traveled Lost Arrow Tip route. There were fat shiny bolts. Just as I reported to Maison the loss of the topo, a piece of paper fell out of the sky and landed right between our feet. The topo! It had been swirling in the Valley wind for over an hour. We jumped on it like two farmers discovering a bag of gold in their crops. It was an omen, and we pushed to the top, making it at last light, a point in the sky, the world fading to black rapidly around us.

I thought if I pushed hard enough I could make anything that I wanted happen. I teamed up with Luke, a porter at the Ahwahnee who would regularly solo Bishops Terrace up and down during his lunch break. We blasted off on The Nose on El Capitan but got stuck in a climbing traffic jam. A full day went by and we were only at the start of the stove legs.

We set up our portaledge and decided to head down in the morning. There was too much waiting around for it to be enjoyable. We broke our portaledge anyway when we were taking it down. Back on the ground, we drank beer and watched as a rappelling climber above got their hair stuck in a GriGri. He cut it off with a knife and we watched it peacefully float down to us over the screams.

I left for the season that afternoon. In my mind, an ascent of El Cap would’ve legitimized my existence as a bed-making dirtbag rock climber. Instead, it never happened and I felt wayward and listless. I made my way back to the rainy north. The insecurities I felt about my decision to live this way were sharper. I was unsure of who I was or where I was going.

A close friend from my childhood had succumbed to opiates that summer and his death was making me question what was important. I focused not only on what I had gained but also what was being lost while living this carefree, unplugged life in Yosemite. I steadily advanced into the Pacific Northwest. Soon enough, droplets of water began to blur my vision. I wasn’t sure if they were tears or the first raindrops starting to fall.

2019

Caroline graduated from college that spring and for the first time, we traveled to Yosemite together. We left Portland at sunrise and began the long slog south. The set-up this year was going to be a little different. The year before, I had met Nicole. Nicole was someone who climbed hard, yet still held down a legitimate job in the outdoor industry, which at this point was something I was looking to get into. With her help, I got a job leading backpacking trips in the high country instead of scrubbing piss off toilets.

Caroline was back at the lodge where she was quietly becoming a housekeeping legend, to the point where the management pulled her aside and wanted to know how they could retain more employees. It also meant she had a tent in Boys Town again, and we lived a second summer in those quiet tent rows. We rolled into the Valley at night, and immediately met up with Micah to play some ping-pong in new housing. Micah was a housekeeper and would dress up in Kimonos and other costumes when partying in the tents. He later started organizing these crazy poker games outside the now permanently closed CC, next to an enormous pile of broken down toilets.

The characters around us were gradually changing, like sand dunes in the Sahara Desert. The Valley was starting to feel a little smaller, and some familiar faces weren’t around this year. But the hole that we felt slowly filled in and the circle, on the verge of shrinking, once again began to grow. There were new climbing partners in the mix, and getting to share wild adventures with a whole new batch of amazing people. It felt just as much of a privilege the second time around.

This year we were focusing on free climbing. Because isn’t the point of wall climbing to free climb as much as possible? I was trying to become comfortable on Yosemite 5.10 in all styles, which I learned quickly in the earlier parts of that year was easier said than done. Still, climbs like South by Southwest, Center of the Universe, Flying in the Mountains, and OZ showed that I was slowly making progress.

Strangely, I was starting to feel kind of old. Or at least older. At least once a day I would see college kids clanking off towards Jam Crack or Ranger Crack or Grant’s Crack, and their stoke would be palpable. I lounged on bear boxes, taking as many rest days as climbing days it seemed. It didn’t feel right to be feeling slightly jaded, but there it was.

One day, Caroline and I went to Luke’s tent and asked to borrow some totems because we wanted to climb Serenity Crack. After getting the cams we realized a group of younger climbers had been listening to our whole conversation. At first I was kind of annoyed, but realized they were just young climbers obsessed to the last drop, like we had been.

It was also around that time that Devin, the notorious gear thief of that summer was at his height. We had heard about a lot of stuff going missing around Camp 4, including a friend's bike, but couldn’t put a face to the thief yet. Caroline, Matt - another guide I worked with, and I were casually climbing at Grant’s Crack one evening when a random guy walked up. He had a crazy, chaotic energy that was unnerving.

He boasted “I was gonna solo this but saw you guys had a rope up so maybe I’ll hop in with you guys” and before I knew it, I was giving him a belay while he climbed Grant’s Crack. He looked pretty shaky for someone who was planning on soloing. It wasn’t long after that we found out this guy had been the gear thief and was arrested by the National Park Service rangers. We were glad we got away with only giving him a toprope lap.

On top of all this I had my work. Two years in the park and I had never spent a night in the Yosemite backcountry, but now I was doing it every week. The job breathed some life into parts of me that had been dead while I was working at the lodge. There was more meaning, more joy, and more beauty. Some clients would reach the summit of Half Dome and burst into tears. The schedule was demanding, and there was less time for climbing than before. But all the time in the high country left me refreshed and more stoked to climb when I would get the chance.

The season went by, and the oaks were turning yellow. It was time to try El Cap. Caroline had turned into a true crack fiend and was leading harder on gear than she ever had on bolts that summer, and she was getting interested in wall climbing. We decided to try Lurking Fear. We were a little too ambitious. It was her first wall climb and my first of that year. We ripped a ladder a third of the way up and decided to call it. We didn’t have the spirit. Before the climb, we had both talked about how we were excited to leave afterwards, Valley life was starting to wear us down.

I was disappointed, but not overly so. I was starting to address the things that had a habit of dragging me under. My performance had become less and less associated with my sense of self-worth. Other things besides climbing were starting to play that role - my community, my work, and experiencing the majesty of Yosemite itself.

We were feeling the pull of the desert like we had felt the pull of Yosemite. Flush with cash from working all summer, we packed up the car and headed east, over the mountains, across the enormous saucepan desert, and finally cruising down into the land of mesas, towers, and canyons.

2020

One hot, late-spring morning, we rolled out of Moab bound for Yosemite. It was time. Covid-19 was starting to take a toll on the small, isolated town. We had ridden out the first wave of the virus in a rented room at a house. Our restaurant jobs were increasingly maddening by the day.

We lounged in the park the day before leaving, and for the first time ever, I felt anxiety over moving and going back to California. The years on the road were starting to take their toll. Maybe, I was tired of running around. We pointed the car west across the desert, taking Highway 50, the “Loneliest Road in America” from Ely to Carson City, Nevada.

We both had the rugs pulled out from under us with our respective work plans. What was meant to be a week or two in Tahoe turned into seven, and we roamed up and down the east side from Bridgeport to Lone Pine with Nicole and Matt - work buddies. Eventually there was guiding to be done and Caroline landed a front desk job at Rush Creek, along Highway 120.

We had returned to Yosemite as much out of necessity than anything else, which felt strange and not quite right. Yosemite was our community and our careers at this point, and working only intermittently during Covid lockdowns, we really needed to make some money. I turned 25 at the beginning of the summer, and spent the day reflecting. More and more I was desiring some stability.

Caroline had a degree in mathematics and was looking at jobs in her field, which would require living near the big city. The writing was on the wall that this might be our last summer living in Yosemite. At least for a while.

One more year. I decided to create no concrete climbing goals. I just wanted to have fun and climb as much as I could without any pressure. El Cap was still on my mind, but if there was anything that I had learned about wall climbing it was not to force it.

Seven weeks after leaving our house in Moab, Caroline and I finally, finally made it home. We rolled into the Valley late in the afternoon, parked at the Ahwahnee, and headed straight for the wall. We knew where we wanted to be.

Caroline and I swapped leads to Dinner Ledge. We took a new free variation on the second pitch. We were heading up Skull Queen this time.

We made the ledge by dinner and waited out a quick rainshower. It was Caroline’s first night on a wall. We had a few sips of wine. Getting ready for the Kor Roof, I remembered how afraid I had been before. This night, instead of being afraid, I was delighted. Soft pink clouds floated out from behind Half Dome. Ravens floated on updrafts. We were home. We were climbing, and it was fun. I felt a peace and a clarity that can only come from the kind of light that shines on Yosemite Valley. It only lasted a moment, then it was gone. But it was enough. I reached the anchors at last light, fixed the line, kicked off, and glided down into the darkness.

We ended up rappelling three pitches from the top. It was too hot. It didn’t bother me at all, we had gotten the experience we came for. A night on the wall, some fun climbing. Bailing didn’t bother me as much anymore because by this time I had more fulfillment in other areas of my life than I had when I was younger. Slowly but surely, I was growing up.

Still, I didn’t want to go out quietly. Nicole wanted to climb a big wall, so we decided to go for the Regular Northwest Face of Half Dome in a day. The decision went back to the idea of a progression. Two years before, the climb had taken everything I had. Had we been lucky? Could we do it in better style? I wanted to know.

We ended up rappelling three pitches from the top. It was too hot. It didn’t bother me at all, we had gotten the experience we came for. A night on the wall, some fun climbing. Bailing didn’t bother me as much anymore because by this time I had more fulfillment in other areas of my life than I had when I was younger. Slowly but surely, I was growing up.

Still, I didn’t want to go out quietly. Nicole wanted to climb a big wall, so we decided to go for the Regular Northwest Face of Half Dome in a day. The decision went back to the idea of a progression. Two years before, the climb had taken everything I had. Had we been lucky? Could we do it in better style? I wanted to know.

We bivvied at the base and the first two blocks went by pretty smoothly. I was feeling powerful and my motivation was unclouded. There is a difference between wanting to climb something versus wanting to have climbed it. I fell 20 feet while following free, there was a lot of rope drag and Nicole was having a tough time pulling it up. Then, we were in the traversing pitches over where the rockfall had occurred in 2015. True to form a couple softball sized rocks whizzed by us here. I had decided to short fix on the bolt ladders, which had always seemed like a technique only crazy speed climbers used, not for mere mortals like myself, but there I was on the bolt ladders in the middle of the massive face of Half Dome, short fixing. I skipped the knot throw by using tension off a bolt and climbing a piece of cord that was hanging down below the belay alcove. It was scary, and maybe not that safe, but it saved us a bit of time.

Nicole took over the lead for the pitches up to Big Sandy but soon confessed she was not feeling it, as all climbers have these moments. The chimneys in that section are strenuous and take tiny gear. Nicole was probably a stronger free climber than I was, yet didn’t have the experience to blend free, French Free, and aid together efficiently yet. All the time I’d spent scrapping around on Yosemite’s walls was starting to pay off and I blasted upward. It was by-any-means-necessary climbing. We reached Big Sandy at sunset, took a rest, then the night shift began.

We decided I would lead to the top in the interest of time, and we crept through the upper pitches of Half Dome in the middle of the night. Sometimes being on the wall can be relaxing and fun - you meet another party that you vibe with or you get to kill some time on a great ledge. Other times it can feel like being on the moon, all alone high on an austere face, not knowing which is closer - the sunset in the rearview mirror or the sunrise on the horizon.

We got to the top at 1:30 a.m., 19.5 hours after starting up. It wasn’t until we were swinging our way down the cables in starlight that I realized I had climbed the wall with no ascenders. I smiled at the stars. They winked back at me “not bad.” My last shred of vigilance was used getting off sub-dome safely, then as soon as I hit flat ground, I tripped and fell face first into the bushes.

In the meantime, we were seeking out climbs that through the years, we had missed. By traveling a little off the beaten path, we discovered a lot of great climbs that are not necessarily thought of as classics. Yosemite was re-inventing itself to us again.

August rolled into September. The falls dried up, and wildfires again began to pop up- up and down California. For us, the summer was a time of dreams when the rest of the year was a time to be burdened with reality. Summer was ending. Caroline was applying for jobs in Seattle and Denver. The idea was to get a steady job and an apartment somewhere, to regroup in private. A reprieve to figure out who we were and where we were going. Then, it happened. A full-time position at an insurance firm materialized for Caroline in Seattle. So that was settled. Mercifully, there was a little bit of time left.

It was one of the worst wildfire seasons in California history, and the park closed for about ten days due to poor air quality. With the park closed, Rush Creek was essentially at the end of a 20-mile dead end road. It was completely quiet there for that time. We were walking back up from swimming in the south fork of the Tuolumne one day when we saw cars passing on the highway.

“Park’s open.”

Ben was suddenly around. He was someone I didn’t know well, but we had overlapped for a year at college and had always wanted to climb together. He had some wall experience and also had done some huge routes down in Cochamo, in Chile. We did a few practice climbs on Freeblast and New Dimensions to get in a groove, then set our sights on The Nose.

Crowds had been a factor on my first attempt of The Nose so we tried to start on a day it was empty, or at least empty-ish. We fixed to Sickle. There were other parties up there, fixing ropes and hanging out. One of the best parts of wall climbing and climbing in general is getting to meet people from all areas and all walks of life. Hanging around chatting, we realized for several parties it was their first wall, including a party of three. We felt pretty confident with an early start we could get ahead and have an open route ahead of us.

Sometimes, it seems, the stars just align in your favor. We passed a party on the hauls up to Sickle, then another getting into the Stove Legs. They took the low variation while we took the Dolt Hole. We lost sight of them for a minute, then we got around the arete and we were a pitch above them. We were climbing in blocks. Ben blasted up the Stove Legs and I took the pitches to El Cap tower. We got there at last light. All of a sudden we were almost halfway up with no one in front of us.

In the morning I led Texas Flake and Boot Flake. Texas Flake ended up being my scariest lead of the climb. Ben did the King Swing with ease and started motoring through the Grey Bands. We were moving fast, our haul bag was pretty light and our docking and lower-out system was on-point. I led the Great Roof, my favorite pitch of the climb. It was here that the exposure began to get really wild, the parties below looking like ants. Then it was Pancake Flake, where we butted up against the back of a team of three doing a 5-day ascent - a group of hilarious guys from Colorado.

We struck a deal that they would bivy at the Glowering Spot, and we would take Camp V, because we were climbing without a portaledge. It got dark, and we had some rum while we waited for them to get above camp V. The next pitch was Hayden’s Corner, and it was the only pitch on the whole climb we did in the dark. But, what is light anyway without a little darkness?

The next day we topped out. A NIAD team finished at the same time as us. I was really happy, but it was a good reminder that the progression will continue. We sauntered down the East Ledges, reaching the Manure Pile parking area right at dusk, and just like that, the climb was over and we were back on the Valley floor.

|

Lounging in the meadow the next day, I experienced a quick moment of grief. Whatever we may have gained by climbing The Nose, the sense of mystique and awe surrounding the wall was gone. There was also the sense of something lost. But, I was already thinking about which El Cap route I wanted to try next.

I said goodbye to Ben the next day in the way that a lot of dirtbags do - with little sadness, as you feel aware of a cosmic plan after those moments you share climbing, that we would re-unite to do it again if we were meant to. “See ya!” A few days later we said goodbye to Yosemite. Caroline and I walked the Valley floor, visiting all our favorite spots - 420 beach, Indian Caves, Mirror Lake, the Couch. Everywhere we looked there were memories. In the forest we could almost see the people we loved, hear their laughter. At the Couch the afternoon light was coming in. The day was ending and in the morning we were driving to Washington. We cried our eyes out. Somehow we had both known to come to this place and we had found each other, and now we were leaving and heading hopefully, towards a new home, together. |

Later, in Washington, the apartment was an assault on all of my instincts. We signed a year lease, which felt more committing than any climbing we had done. I sat at home, not comfortable yet, expecting the people who really lived here to walk in at any moment. I paced around and waited for my new job to start. Soon the days began to run together and Yosemite was already beginning to fade. Big Wall climbing felt like something that someone else did.

The victory of finally climbing El Cap felt a little different than I’d first imagined. I’d envisioned it as an intense moment of personal triumph. Instead, I found myself thinking more about the friends I’d made, the beauty I’d seen and experienced, and the life I was starting to build. I realized, in the end, it wasn’t a story of triumph, but one of gratitude.

The victory of finally climbing El Cap felt a little different than I’d first imagined. I’d envisioned it as an intense moment of personal triumph. Instead, I found myself thinking more about the friends I’d made, the beauty I’d seen and experienced, and the life I was starting to build. I realized, in the end, it wasn’t a story of triumph, but one of gratitude.