A young climber at the gym called me, in all seriousness, a legend the other day. How about that?! Not a has-been, or a climbing relic, but a legend...oh wow… But she was wrong, of course. Real legends belong up there in the pantheon of climbing gods. I’m just old!

I might know what the young lass was getting at though, even if she had chosen entirely the wrong person and an overused descriptor. As climbers we all need to feel we share a history, a central narrative which gives our community a reference point for our attitudes and ethics.

Each generation creates its own local version of this storyline and develops its own local myths and heroes which reflect the continuing evolution of the eccentric, exclusive, obsessive, and increasingly diverse game we play today. These individual stories can help us understand our odd little vertical world, and ourselves, the “Conquistadors of the Useless" (as French guide Lionel Terray described climbers so many years ago.) We need to feel we belong.

So, let me share with you one such story, a story from way back when, about a remarkable Tasmanian who led a remarkable life - a man that few climbers would have heard of but who truly lived “the climber’s dream” – Max Cutcliffe.

First, some context.

Wind the clock back over 90 years. The world was suffering from a deep economic depression which followed the Wall Street Crash in 1929. Times were very, very tough in Bothwell, a tiny, isolated mountain village in the island state of Tasmania. When Max was born in March 1930, his father was reduced to working as a rabbit skinner to feed his family.

As the economy improved over the next few years, the family moved down to Hobart so the kids could go to school. It was during Max's time as an apprentice electrician that he had something of an epiphany, an experience that gave him a sense of direction for the rest of his life:

“We followed a walking track to Cape Raoul and sat atop one of those mighty pillars of sheer rock with the sea smashing into them so far below, and an ocean that went on forever, and there was nobody else around, nobody out to sea, nobody on the land, so quiet, not even a bird twittered, not even a leaf fell…... my life had found a meaning."

I might know what the young lass was getting at though, even if she had chosen entirely the wrong person and an overused descriptor. As climbers we all need to feel we share a history, a central narrative which gives our community a reference point for our attitudes and ethics.

Each generation creates its own local version of this storyline and develops its own local myths and heroes which reflect the continuing evolution of the eccentric, exclusive, obsessive, and increasingly diverse game we play today. These individual stories can help us understand our odd little vertical world, and ourselves, the “Conquistadors of the Useless" (as French guide Lionel Terray described climbers so many years ago.) We need to feel we belong.

So, let me share with you one such story, a story from way back when, about a remarkable Tasmanian who led a remarkable life - a man that few climbers would have heard of but who truly lived “the climber’s dream” – Max Cutcliffe.

First, some context.

Wind the clock back over 90 years. The world was suffering from a deep economic depression which followed the Wall Street Crash in 1929. Times were very, very tough in Bothwell, a tiny, isolated mountain village in the island state of Tasmania. When Max was born in March 1930, his father was reduced to working as a rabbit skinner to feed his family.

As the economy improved over the next few years, the family moved down to Hobart so the kids could go to school. It was during Max's time as an apprentice electrician that he had something of an epiphany, an experience that gave him a sense of direction for the rest of his life:

“We followed a walking track to Cape Raoul and sat atop one of those mighty pillars of sheer rock with the sea smashing into them so far below, and an ocean that went on forever, and there was nobody else around, nobody out to sea, nobody on the land, so quiet, not even a bird twittered, not even a leaf fell…... my life had found a meaning."

|

So started Max’s life journey of climbing and adventure.

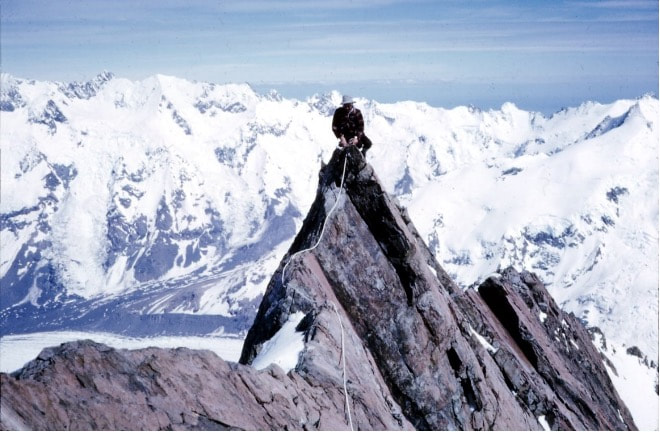

His mountaineering history was extraordinary. As a young lad he honed his skills and fitness exploring the remote and largely uncharted Tasmania’s southwest wilderness: Pindar’s Peak, Precipitous Bluff, Port Davey, and Federation Peak - all with long, arduous, and exposed tramping in all weathers. But this wasn’t enough. As soon as Max could, he was off to the high mountains of New Zealand where he accidently bumped into fellow Australian Faye Kerr, his long-time partner to be. They had first met deep in the wilderness of Tasmania’s southwest a year or so earlier. The 1954 edition of the New Zealand Alpine Journal sums it up: "Two young Australians, who have not been in New Zealand long but who, in the last nine months alone have ascended over forty peaks from Egmont to Earnslaw, including many good climbs in the Mt Cook region." |

The pair was Kerr and Cutcliffe, and their climbs included the second ascent of the now famous Coxcomb Ridge of Mt. Aspiring (with a forced bivouac on the summit), and the Grand Traverse of Mt. Cook (the first by an unguided woman). Ever the master of the understatement and typical of his self-effacing nature, Max’s droll comment on their success was simply, “It was calm and clear on the top and lunch was served."

Max and Faye also climbed ten 3000-meter (10,000-foot) peaks in one season. This was a record that has rarely been matched, and it was the first time - or possibly the second - that was achieved unguided.

All this was accomplished at a time of post-war economic readjustment: money was short, transport limited, and basic climbing equipment was difficult to come by. Many climbers made their own gear when they could or bought ex-Army surplus kit: simple nailed boots, long axes, and nylon hawser-laid ropes. Gortex, harnesses, kernmantle ropes, cams, ice-screws and GPS (the list goes on and on) hadn’t been invented yet!

Max and Faye also climbed ten 3000-meter (10,000-foot) peaks in one season. This was a record that has rarely been matched, and it was the first time - or possibly the second - that was achieved unguided.

All this was accomplished at a time of post-war economic readjustment: money was short, transport limited, and basic climbing equipment was difficult to come by. Many climbers made their own gear when they could or bought ex-Army surplus kit: simple nailed boots, long axes, and nylon hawser-laid ropes. Gortex, harnesses, kernmantle ropes, cams, ice-screws and GPS (the list goes on and on) hadn’t been invented yet!

|

Back in Tasmania and incredibly fit, the pair went on to make the first winter ascent of Federation Peak, the most isolated and exposed mountain in Australia. This involved days of off-track bush-bashing in lousy, cold and wet weather, with leeches, technical rock climbing, airdrops, and near starvation. Max maintained he was essentially a mountaineer, not a rock climber, but it was in this period he also created his signature rock climb in Tasmania, the first ascent of Nicholls Needle in 1954.

Then the couple was off on what turned out to be a seven-year adventure road trip - a tour of the major climbing and skiing areas across Europe, Faye and Max working and playing as they went. Max found employment as an electrician while Faye taught school. They were some of the original "vanlifers," driving round Europe in an old Volkswagen climbing and skiing in Austria, France, Switzerland, Italy, Norway, and Yugoslavia. |

After climbing the Wetterhorn above Grindelwald in Switzerland in 1957, they were asked to join an epic and famous six-day rescue operation mounted to help Italian climbers Corti and Longhi get off the infamous Eiger North Face. Faye and Max carried winching gear to the summit where Lionel Terray was lowered down the face in an attempt to reach the men.

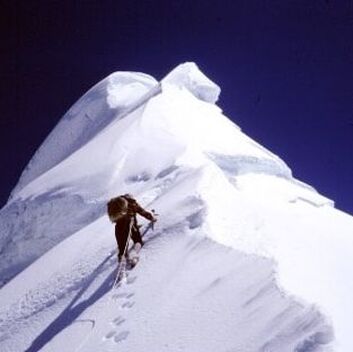

Over time, the Greater Ranges called, and Max set off with his brother and sister-in-law to drive to Pakistan via Turkey, where they climbed Mt Arafat. They continued through Iran, Iraq, and Afghanistan, then over the famous Khyber Pass into Northern Pakistan. In the Swat region they climbed three virgin peaks around 6500 meters (20,000 feet) in the Western Himalaya. The team finished with the first ascent of a peak they estimated at around 7500 meters (25,000 feet) - their altimeter was broken.

Max's adventurous life journey continued - too much to detail here – ice-climbing in Scotland, tramping the Irish hills, walking across England, and then eventually weaving his way further across the world.

Max joined up with his old buddy, Atilla Vrana, to climb in the Rockies in Colorado and Denali, Alaska - the highest mountain in North America - where Max lost most of a big toe to frostbite.

Over time, the Greater Ranges called, and Max set off with his brother and sister-in-law to drive to Pakistan via Turkey, where they climbed Mt Arafat. They continued through Iran, Iraq, and Afghanistan, then over the famous Khyber Pass into Northern Pakistan. In the Swat region they climbed three virgin peaks around 6500 meters (20,000 feet) in the Western Himalaya. The team finished with the first ascent of a peak they estimated at around 7500 meters (25,000 feet) - their altimeter was broken.

Max's adventurous life journey continued - too much to detail here – ice-climbing in Scotland, tramping the Irish hills, walking across England, and then eventually weaving his way further across the world.

Max joined up with his old buddy, Atilla Vrana, to climb in the Rockies in Colorado and Denali, Alaska - the highest mountain in North America - where Max lost most of a big toe to frostbite.

|

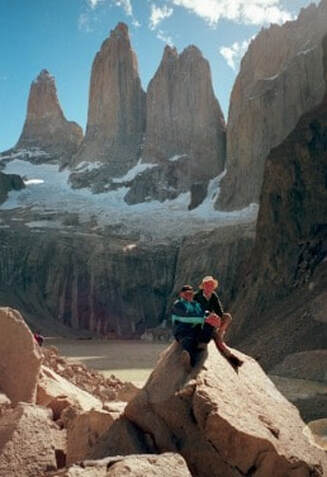

In 1998, Max even travelled down to Cape Horne to cross the Patagonia ice cap. Then he was back on home turf again - Mt. Cook, Tasman, and Malte Brun in New Zealand. At the age of 75, the dream continued with a last trip up Federation Peak with Atilla - some fifty years after his first ascent.

But Max was more than a climber, he was an adventurer: inquisitive, involved, and fascinated by the history of the places he visited, exploring cities and their museums, cathedrals, restaurants, and theatres. The Boy from Bothwell took the roads less travelled - figuratively and literally - and soaked it all up as he went. His trusty VW not only took him around Europe, but also through Egypt, and Tunisia. He went from Europe to central Africa and the Congo, then on down south to Johannesburg in an old army Bedford truck. Along the way Max got caught up in a revolution and riot. He was robbed in Zambia and again in Kenya, and before he could cross the Zambesi their ferry was blown up by terrorists. He explored a gorilla sanctuary in Rwanda and climbed Mt. Kilimanjaro in Tanzania (the highest mountain in Africa at 5895 meters/ 19,340 feet). |

Max drove from London to New Delhi, India and climbed Mt. Ararat (5,137 meters /16,854 feet) in Turkey on the way - getting robbed again! He went across Canada from coast to coast and enjoyed cruises with his wife Margaret. There were regular trips to London, and in later years back and forth annually from his houses in Vancouver, Canada and Hobart, Tasmania.

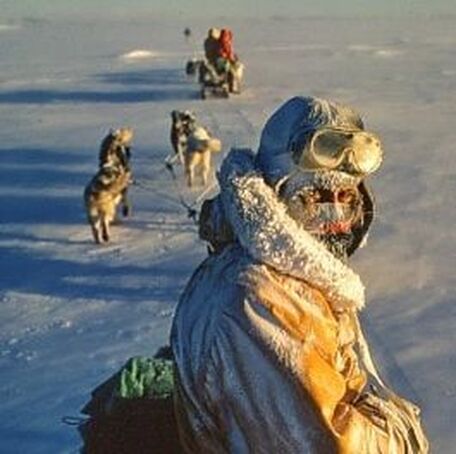

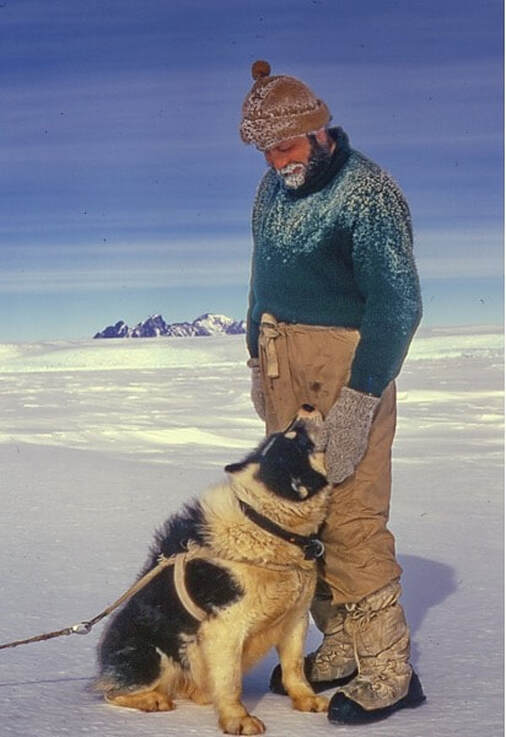

Max talked of another epiphany, an earlier one when he was still at school and the kids were shown a film of Scott in the Antarctic – it started a lifelong ambition to go there, a dream that eventually came true in 1961 and again in 1972 when he over-wintered at the Australian Mawson Station, nestled below the Framnes Mountains. Virgin peaks to climb, exploring the high ice plateau and out across the sea ice with dog-sledges, travelling out to the Prince Charles Range and climbing Mt Creswell, skiing, wildlife and wilderness everywhere, all his dreams come true. For his efforts he was awarded the Australian Polar Medal in 1979 , had a mountain named after him, Cutcliffe Peak, in the Prince Charles Mountains, and a photograph on an Australian stamp.

Max talked of another epiphany, an earlier one when he was still at school and the kids were shown a film of Scott in the Antarctic – it started a lifelong ambition to go there, a dream that eventually came true in 1961 and again in 1972 when he over-wintered at the Australian Mawson Station, nestled below the Framnes Mountains. Virgin peaks to climb, exploring the high ice plateau and out across the sea ice with dog-sledges, travelling out to the Prince Charles Range and climbing Mt Creswell, skiing, wildlife and wilderness everywhere, all his dreams come true. For his efforts he was awarded the Australian Polar Medal in 1979 , had a mountain named after him, Cutcliffe Peak, in the Prince Charles Mountains, and a photograph on an Australian stamp.

With the adventure there was also tragedy. Max suffered the heart-breaking loss of Faye. After surviving the avalanches on Annapurna III in the Himalaya, Faye died in Calcutta from a stomach disease. In Max's words, “the mountains will never be as dazzling without her around."

|

Max also lost a good friend from a fall while they were climbing together in New Zealand. His brother Roy died - probably from altitude sickness - while they were climbing together in Pakistan, and in Antarctica, Ken Wilson, a fellow expeditioner, died in tragic circumstances from a perforated stomach ulcer while they were sledding to Fold Island. Then Max lost his wife Margaret, who was also a travelling and skiing companion of many years, after she had several strokes. Max was fortunate too though, as he entered the last phase of his life with his Canadian partner and confidante, poet Cathy Morris.

Max was nothing if not resilient. In his eighties, he embarked on a new career, that of a writer. In 2019, Max published the history of his mother’s life on Bruny Island, called Bruny Island Girl. In 2020 he released Early Years at Mawson, a photographic memoir of his two years in Antarctica. And, in 2021 Max published his first climbing adventure novel, No Trails to Mawson. Legends and myths wither and die unless they are told and re-told and shared. With all of his incredible accomplishments, first ascents, and recent publications, why haven’t we heard of Max before? Why hasn’t his amazing life been celebrated more widely? Partly it was because there weren’t the various social media outlets available in his day. Partly it was because Max was from a different time, when publicity was not sought, and self-aggrandizement was frowned upon. But it was also because Max climbed for himself, and himself alone. Apart from an occasional article in a local Tasmanian walking club journal, Max would never share his life history. He also wouldn’t allow me to write anything about him while he was alive. But now, I would love for him to have the recognition by his peers that he so richly deserved. |

|

I made the mistake once of asking Max when he had given up mountaineering. He was most indignant and asked me what on earth made me think he had retired. He was then 84.

Max Cutcliffe died in 2021 in Hobart, Tasmania at aged 91. Was Max a legend? I think so. At the very least he makes us mere mortals look very ordinary. Vale Max. -- Tony Mckenny, Tasmania, 2022 |