Cover Photo Above: Climber Naomi Gibbs is carried out after a fall snaps her achilles tendon.

|

|

“On belay!”

“Belay’s on!”

“Climbing!”

“Climb on!”

You are filled with excitement and anticipation as you call out those familiar commands. You pull yourself onto the beginning holds of your project. “Today is the day,” you think to yourself while working your way up the route, linking the moves you have been practicing and daydreaming about for weeks. As you near the top of the route, you hear a scream from the route next to you. You look over just in time to see a climber impact the ground below, narrowly missing his belayer. Your excitement quickly turns to dread. A million thoughts race through your mind at once. “What happened? Is he okay? Why isn’t he moving? How far did he fall? What do I do?”

You quickly make your way to the next bolt, clip into your carabiner, and yell “take!” to your partner. You lower, untie, and quickly make your way to the fallen climber just in time to find him standing up with the assistance of his climbing partner. Miraculously, he is mostly unscathed aside from a cracked helmet and a few cuts and bruises. They thank you for your concern, pack up their things, and return to their car, leaving you and your climbing partner alone at the crag. You think to yourself “Wow, that was a close call!” and continue your day as if nothing had happened. After all, nobody was hurt, so why should your plans change?

The next day, you return to the crag for the send of your project but today feels different. The once-routine act of putting on your harness creates a pit in your stomach. Those same climbing commands that usually elicit excitement, now fill you with dread. You no longer care about sending your project. Frustrated and confused, you bail from the route and spend the rest of the day on climbs that are several grades below your ability; ones that pose little risk of falling.

A week later, you go to a different crag with hopes of reinvigorating your enthusiasm for climbing. However, upon arrival you quickly realize that you lack the desire to lead any routes. You make an excuse about a tweaked ankle and belay your partner on lead, cleaning his routes after he is done. This feels better, but now you feel disappointed in yourself for taking a backseat to your climbing partner. You have always felt a healthy sense of competition with him, but today you just don’t care.

A month later, your phone goes off and your heart starts racing; it’s the familiar sound of your climbing partner’s ringtone. “He wants to go climbing,” you think to yourself. He has texted you several times over the past few weeks, but you have avoided responding. You gather up the courage to text him back and suggest meeting up for a hike instead. His response is filled with disappointment, which makes you feel even worse.

Eventually, you stop responding to his texts completely. You start avoiding social events. Your alcohol intake increases; it’s the only thing that dulls the intense sadness you feel about losing your passion for climbing. Your quality of sleep decreases and you start feeling irritable throughout the day, causing you to snap at your coworkers. “What has happened to me?” you think to yourself.

Thankfully, we now understand these as hallmark signs of stress injury formation, an exposure injury type that has begun to capture attention in the mental health world. This injury type was initially identified by the military and has only recently been applied to other groups including humanitarians, first responders, search and rescue, ski patrol, and outdoor recreationalists.

Stress injury formation occurs following exposure to trauma or psychological stress, sometimes weeks, months, or even years later. In the context of climbing and outdoor recreation, it can occur after witnessing or being a first responder to an accident or near-miss. Surprisingly, it can even occur after listening to a detailed account of these events. The incredible adaptability of the human brain often allows one to carry on following exposure to psychological stress, but after repeated exposure, the body eventually slips into survival mode, secreting copious amounts of cortisol and initiating stress injury formation. Symptoms usually progress in a linear fashion, gradually becoming more severe, as portrayed in the above anecdote.

Left unaddressed, stress injuries can lead to a severe decline in quality of life. It can also lead to serious mental health problems including acute stress disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder. This process is comparable to that of untreated physical repetitive strain leading to physical stress injuries including damaged bones, muscles, tendons, ligaments, and nerves. When experiencing physical strain, it makes sense to seek help before it becomes a physical injury. So how do we prevent a stress injury? Evidence shows that early recognition and mitigation are the most effective ways to support someone at risk for stress injury formation.

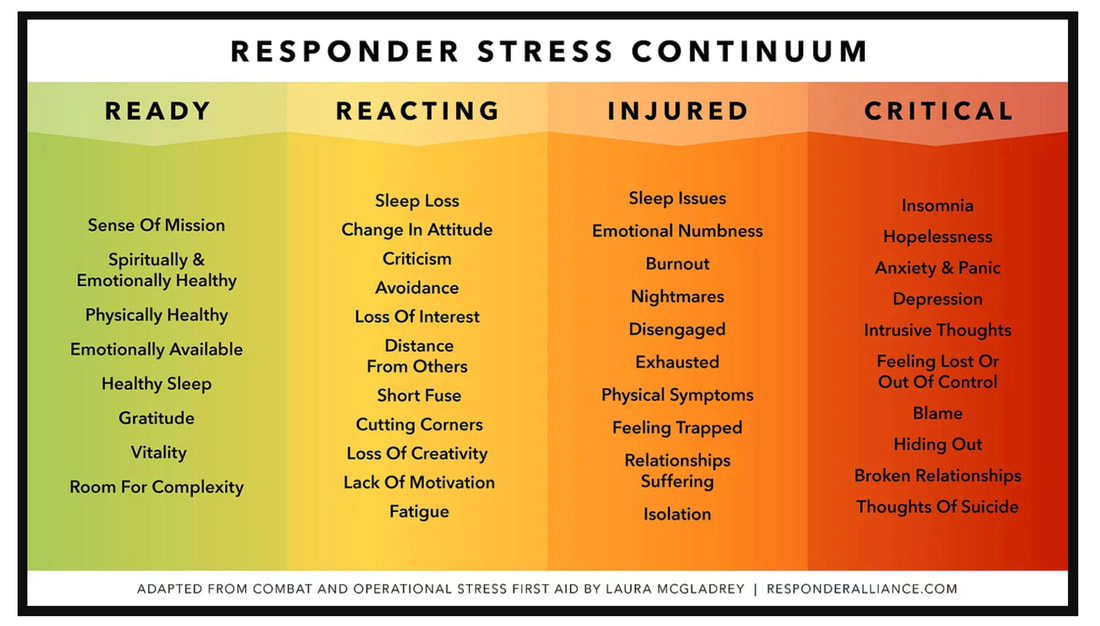

Early recognition can be accomplished by identifying the symptoms of stress injury formation and seeking intervention before they worsen. The Responder Stress Continuum (figure 1) is an invaluable tool for assessing how efficiently you or someone you know is coping following exposure to psychological stress. A person who is “reacting” is experiencing the initial changes of psychological stress. As discussed previously, human adaptability often allows us to reverse the effects and return to “ready.” However, additional exposures may push us towards the “injured” and “critical” stages of the continuum, potentially requiring external support from a mental health professional.

“Belay’s on!”

“Climbing!”

“Climb on!”

You are filled with excitement and anticipation as you call out those familiar commands. You pull yourself onto the beginning holds of your project. “Today is the day,” you think to yourself while working your way up the route, linking the moves you have been practicing and daydreaming about for weeks. As you near the top of the route, you hear a scream from the route next to you. You look over just in time to see a climber impact the ground below, narrowly missing his belayer. Your excitement quickly turns to dread. A million thoughts race through your mind at once. “What happened? Is he okay? Why isn’t he moving? How far did he fall? What do I do?”

You quickly make your way to the next bolt, clip into your carabiner, and yell “take!” to your partner. You lower, untie, and quickly make your way to the fallen climber just in time to find him standing up with the assistance of his climbing partner. Miraculously, he is mostly unscathed aside from a cracked helmet and a few cuts and bruises. They thank you for your concern, pack up their things, and return to their car, leaving you and your climbing partner alone at the crag. You think to yourself “Wow, that was a close call!” and continue your day as if nothing had happened. After all, nobody was hurt, so why should your plans change?

The next day, you return to the crag for the send of your project but today feels different. The once-routine act of putting on your harness creates a pit in your stomach. Those same climbing commands that usually elicit excitement, now fill you with dread. You no longer care about sending your project. Frustrated and confused, you bail from the route and spend the rest of the day on climbs that are several grades below your ability; ones that pose little risk of falling.

A week later, you go to a different crag with hopes of reinvigorating your enthusiasm for climbing. However, upon arrival you quickly realize that you lack the desire to lead any routes. You make an excuse about a tweaked ankle and belay your partner on lead, cleaning his routes after he is done. This feels better, but now you feel disappointed in yourself for taking a backseat to your climbing partner. You have always felt a healthy sense of competition with him, but today you just don’t care.

A month later, your phone goes off and your heart starts racing; it’s the familiar sound of your climbing partner’s ringtone. “He wants to go climbing,” you think to yourself. He has texted you several times over the past few weeks, but you have avoided responding. You gather up the courage to text him back and suggest meeting up for a hike instead. His response is filled with disappointment, which makes you feel even worse.

Eventually, you stop responding to his texts completely. You start avoiding social events. Your alcohol intake increases; it’s the only thing that dulls the intense sadness you feel about losing your passion for climbing. Your quality of sleep decreases and you start feeling irritable throughout the day, causing you to snap at your coworkers. “What has happened to me?” you think to yourself.

Thankfully, we now understand these as hallmark signs of stress injury formation, an exposure injury type that has begun to capture attention in the mental health world. This injury type was initially identified by the military and has only recently been applied to other groups including humanitarians, first responders, search and rescue, ski patrol, and outdoor recreationalists.

Stress injury formation occurs following exposure to trauma or psychological stress, sometimes weeks, months, or even years later. In the context of climbing and outdoor recreation, it can occur after witnessing or being a first responder to an accident or near-miss. Surprisingly, it can even occur after listening to a detailed account of these events. The incredible adaptability of the human brain often allows one to carry on following exposure to psychological stress, but after repeated exposure, the body eventually slips into survival mode, secreting copious amounts of cortisol and initiating stress injury formation. Symptoms usually progress in a linear fashion, gradually becoming more severe, as portrayed in the above anecdote.

Left unaddressed, stress injuries can lead to a severe decline in quality of life. It can also lead to serious mental health problems including acute stress disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder. This process is comparable to that of untreated physical repetitive strain leading to physical stress injuries including damaged bones, muscles, tendons, ligaments, and nerves. When experiencing physical strain, it makes sense to seek help before it becomes a physical injury. So how do we prevent a stress injury? Evidence shows that early recognition and mitigation are the most effective ways to support someone at risk for stress injury formation.

Early recognition can be accomplished by identifying the symptoms of stress injury formation and seeking intervention before they worsen. The Responder Stress Continuum (figure 1) is an invaluable tool for assessing how efficiently you or someone you know is coping following exposure to psychological stress. A person who is “reacting” is experiencing the initial changes of psychological stress. As discussed previously, human adaptability often allows us to reverse the effects and return to “ready.” However, additional exposures may push us towards the “injured” and “critical” stages of the continuum, potentially requiring external support from a mental health professional.

|

|

Mitigation can be accomplished by administering Psychological First Aid either during or immediately following exposure to psychological stress. Psychological First Aid is a process that provides the brain with a sense of safety, allowing it to relax and escape survival mode. This helps prevent the initiation of survival mode and stress injury formation. The first version of Psychological First Aid was used to support traumatized soldiers during World War I. Since then, it has continued being utilized by the military and was recently adapted by APRN Laura McGladrey and the Responder’s Alliance for use by first responders and rescuers.

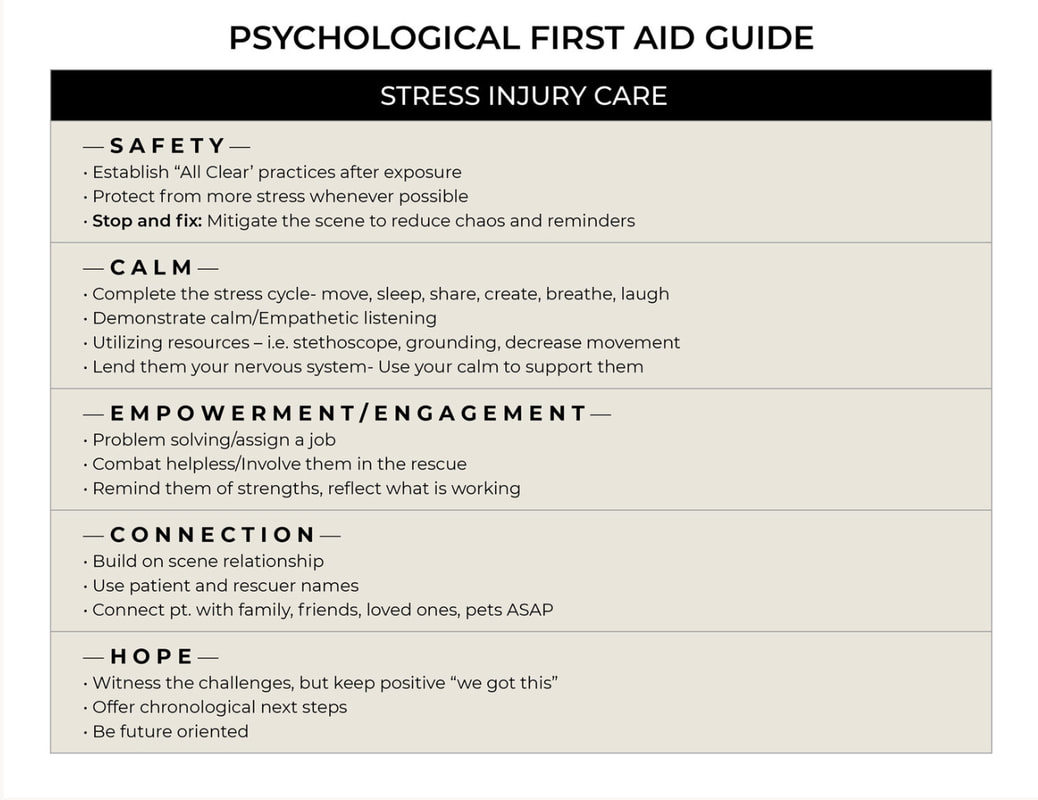

The process of Psychological First Aid is composed of five tools that can be learned and performed by anyone (figure 2).

The first tool is “safety.” Following an accident or a near-miss, it is important to first establish safety of the scene and protect all parties from further psychological stress. This can be achieved by removing hazards or items from victims that serve as reminders of the psychological stressor. This can be as simple as removing climbing gear, covering up a blood stain, or facing victims away from the accident scene. Safety can also be established by making statements that contain the phrase “now that you’re safe.”

The second tool is “calm.” Finding your own calm before helping others allows you to lend victims your nervous system, facilitating their calm. This can be accomplished by first acknowledging the situation, then taking a deep breath and holding it for a few seconds before attempting to help others. You can also induce calm after experiencing a psychological stressor by completing the stress cycle. This is achieved by participating in physical activity, getting a full night’s sleep, sharing your experience with others, doing something creative, breathing, and laughing.

The third tool is “empowerment/engagement.” During survival mode, the brain often feels hopeless. The best way to combat this feeling is by engaging victims in their own rescue. This can be accomplished by assigning simple tasks to those who are impacted, such as providing details about the event. Feelings of empowerment can also be increased by remembering your own strengths and reminding victims of theirs.

The fourth tool is “connection.” Connection to loved ones often correlates with feelings of safety. Because of this, it is important to assure victims that you are not leaving them. It is also helpful to use their names frequently, especially during the beginning of a rescue. Once victims are stabilized, help them contact their loved ones and reestablish connection. If you are the one who has experienced the psychological stressor, contact your own loved one to help induce a feeling of safety.

The fifth tool is “hope.” Immediately following an accident or near-miss, it is necessary to acknowledge the challenges but to also state the positives. Though you might be stranded in the middle of nowhere with a broken leg, remember that your partner knows your location and that you have enough food and water to last until tomorrow. Hope can also be established with statements like “we got this.”

The process of Psychological First Aid is composed of five tools that can be learned and performed by anyone (figure 2).

The first tool is “safety.” Following an accident or a near-miss, it is important to first establish safety of the scene and protect all parties from further psychological stress. This can be achieved by removing hazards or items from victims that serve as reminders of the psychological stressor. This can be as simple as removing climbing gear, covering up a blood stain, or facing victims away from the accident scene. Safety can also be established by making statements that contain the phrase “now that you’re safe.”

The second tool is “calm.” Finding your own calm before helping others allows you to lend victims your nervous system, facilitating their calm. This can be accomplished by first acknowledging the situation, then taking a deep breath and holding it for a few seconds before attempting to help others. You can also induce calm after experiencing a psychological stressor by completing the stress cycle. This is achieved by participating in physical activity, getting a full night’s sleep, sharing your experience with others, doing something creative, breathing, and laughing.

The third tool is “empowerment/engagement.” During survival mode, the brain often feels hopeless. The best way to combat this feeling is by engaging victims in their own rescue. This can be accomplished by assigning simple tasks to those who are impacted, such as providing details about the event. Feelings of empowerment can also be increased by remembering your own strengths and reminding victims of theirs.

The fourth tool is “connection.” Connection to loved ones often correlates with feelings of safety. Because of this, it is important to assure victims that you are not leaving them. It is also helpful to use their names frequently, especially during the beginning of a rescue. Once victims are stabilized, help them contact their loved ones and reestablish connection. If you are the one who has experienced the psychological stressor, contact your own loved one to help induce a feeling of safety.

The fifth tool is “hope.” Immediately following an accident or near-miss, it is necessary to acknowledge the challenges but to also state the positives. Though you might be stranded in the middle of nowhere with a broken leg, remember that your partner knows your location and that you have enough food and water to last until tomorrow. Hope can also be established with statements like “we got this.”

|

|

The dissemination of Psychological First Aid and Stress Continuum resources to the climbing community is crucial in the early recognition and mitigation of stress injury formation. These resources will allow community members to support each other following psychological stress exposure and ideally decrease the number of people who develop a serious mental illness. It will also help community members identify themselves or someone else who may be experiencing stress injury formation, allowing them to obtain external help sooner before quality of life is impacted. As a by-product, discussion of this topic increases awareness of mental illness and decreases stigma within the community.

If you or someone you know has experienced trauma or are suffering from symptoms like those described in this article, help is available. Visit www.psychologytoday.com/us and use their “Find a Therapist” search to find a practitioner who treats patients in your state and accepts your insurance. You can also search the mental health directory at americanalpineclub.org/grieffund to find a practitioner experienced in treating trauma and grief related to outdoor recreation.

Want to learn more about stress injury formation, trauma, and Psychological First Aid? Visit responderalliance.com to explore an array of resources and trainings and to connect with members of your community. Also, be sure to check out an incredible interview about Psychological First Aid with Laura McGladrey on the Sharp End Podcast, episode 34. You can also visit americanalpineclub.org/grieffund for additional resources including psychoeducation, support groups, and a story archive.

Are you or someone you know thinking about suicide?

Call the 988 Suicide and Crisis Lifeline immediately by dialing 988. This service provides free and confidential support 24/7. You can also call 911 or go to your nearest emergency room.

If you or someone you know has experienced trauma or are suffering from symptoms like those described in this article, help is available. Visit www.psychologytoday.com/us and use their “Find a Therapist” search to find a practitioner who treats patients in your state and accepts your insurance. You can also search the mental health directory at americanalpineclub.org/grieffund to find a practitioner experienced in treating trauma and grief related to outdoor recreation.

Want to learn more about stress injury formation, trauma, and Psychological First Aid? Visit responderalliance.com to explore an array of resources and trainings and to connect with members of your community. Also, be sure to check out an incredible interview about Psychological First Aid with Laura McGladrey on the Sharp End Podcast, episode 34. You can also visit americanalpineclub.org/grieffund for additional resources including psychoeducation, support groups, and a story archive.

Are you or someone you know thinking about suicide?

Call the 988 Suicide and Crisis Lifeline immediately by dialing 988. This service provides free and confidential support 24/7. You can also call 911 or go to your nearest emergency room.

Jamie Lange is a Psychiatric-Mental Health Nurse Practitioner who loves to rock climb, canyoneer, mountain bike, ski, and backpack. She is passionate about reducing the stigma of mental health and helping those affected rediscover their passions.