On April 15, 2020 legendary English climber Joe Brown died at the age of 89. British climber and award-winning author, Paul Pritchard, honors Joe in this piece "Remembering Joe Brown."

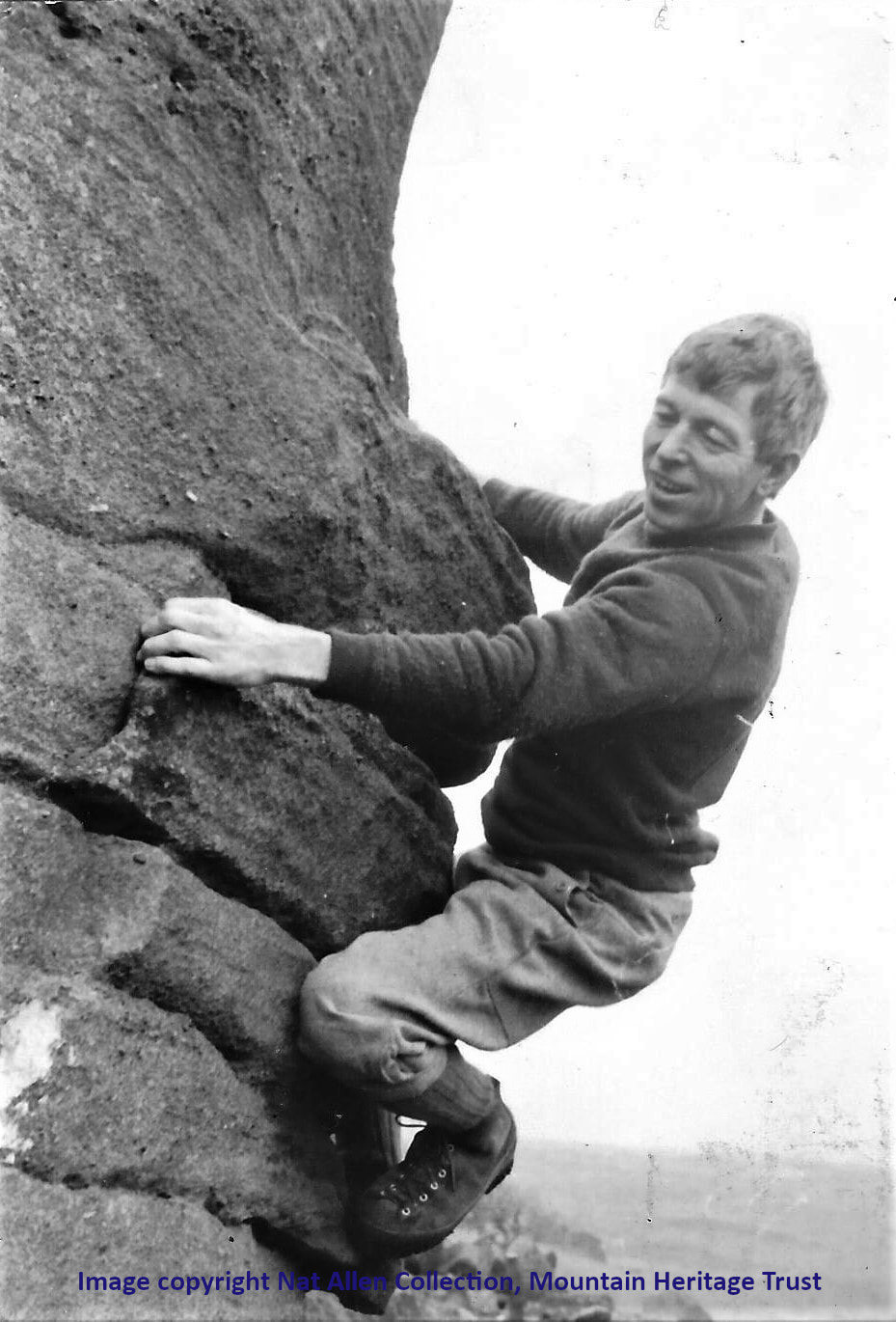

Wales 1989.

Joe Brown and Mo Anthoine had come up with the idea of escorting a band of young hot-shot climbers to the Himalayas. For Johnny Dawes, Bob Drury, and me, it was to be our first time in the "Greater Ranges." Our trio of lycra clad "Biafran Sparras" were to join forces with young mountaineers Joe Simpson and Simon Yates, who were still riding the wave of Suila Grande and Touching The Void fame. The trip was going to be called the "Youth in Asia" expedition.

Joe and Mo were going to accompany us as the "old guard." I couldn’t quite believe it. Here we were going on an expedition to a Himalayan giant with "The Human Fly," the greatest climber in Britain.

We had a meeting in Pete’s Eats (the climber's cafe in Llanberis, Wales) where Joe and Mo showed us a photo of the North Face of Thalay Sagar.

“What do you think of this bloody thing?” asked Mo.

Frankly, it looked terrifying. A 600m ice wall led to a series of rock buttresses the height of El Capitan - a cliff none of us had actually climbed to but which we had seen the photos in Yosemite Climber.

Our eyes naturally settled on a rock buttress high up on the left of the face. Mo pointed to the lower ice face, “These are never as steep as they look head on.”

We let out a collective sigh of relief. Joe leaned in close and sipped his strong tea.

“But the rock is steep. Look it’s bare of snow.” Joe fingered the upper buttress in the magazine. (This actual line was eventually climbed by a crack Russian team in 2017).

Mo was the excitable driving force, while Joe maintained a quiet sobriety. He was the spirit level of the expedition.

Bob, Johnny and I would work with Joe behind his famous climbing shop "Joe Brown" on the Strydd Fawr (high street) in Llanberis. He took great interest in our home-made porta-ledges and weight tested them with us - i.e. bounced in them. He taught us how to overlock stitch the webbing for extra strength on the sewing machine.

We also had a tour of Mo’s, and his wife Jackie’s, Snowdon Mouldings factory, situated an old Welsh chapel on Strydd Goodman. There we each had made colourful fibreglass Joe Brown helmets. These famous lids were worn by every climber up until the late 80s when they were superseded by more lightweight plastic ones.

At that point, in the late 80s, I was lodging in Joe’s daughter, Zoe’s house. Joe would turn up every week to do maintenance on the rather dilapidated structure. During the week, Zoe, Ben Pritchard, Nick Harms, and I would try our damnedest to undo all the repairs Joe had made to the terraced house. We saw it as our prerogative. And, so that ‘Wonder Man’, ‘Baron Brown’, ‘The Human Fly’ would patiently return to repair the stair rail, the broken toilet or fix a hole in the roof.

Of course I knew of Joe’s rock climbs. Everybody did. I grew up in Manchester and caught the X10 bus to the Peak District every weekend. I had climbed The Right Unconquerable, Quietus, Avalanche Wall, the Curbar Cracks of Right Eliminate, Peapod, and Elder Crack, when I was a 16-year-old lad. Before the advent of modern gear these climbs were truly frightful ordeals. But, specialised rock climbing shoes and camming devices, had made them much safer propositions. They had become a right of passage for young climbers.

Joe Brown and Mo Anthoine had come up with the idea of escorting a band of young hot-shot climbers to the Himalayas. For Johnny Dawes, Bob Drury, and me, it was to be our first time in the "Greater Ranges." Our trio of lycra clad "Biafran Sparras" were to join forces with young mountaineers Joe Simpson and Simon Yates, who were still riding the wave of Suila Grande and Touching The Void fame. The trip was going to be called the "Youth in Asia" expedition.

Joe and Mo were going to accompany us as the "old guard." I couldn’t quite believe it. Here we were going on an expedition to a Himalayan giant with "The Human Fly," the greatest climber in Britain.

We had a meeting in Pete’s Eats (the climber's cafe in Llanberis, Wales) where Joe and Mo showed us a photo of the North Face of Thalay Sagar.

“What do you think of this bloody thing?” asked Mo.

Frankly, it looked terrifying. A 600m ice wall led to a series of rock buttresses the height of El Capitan - a cliff none of us had actually climbed to but which we had seen the photos in Yosemite Climber.

Our eyes naturally settled on a rock buttress high up on the left of the face. Mo pointed to the lower ice face, “These are never as steep as they look head on.”

We let out a collective sigh of relief. Joe leaned in close and sipped his strong tea.

“But the rock is steep. Look it’s bare of snow.” Joe fingered the upper buttress in the magazine. (This actual line was eventually climbed by a crack Russian team in 2017).

Mo was the excitable driving force, while Joe maintained a quiet sobriety. He was the spirit level of the expedition.

Bob, Johnny and I would work with Joe behind his famous climbing shop "Joe Brown" on the Strydd Fawr (high street) in Llanberis. He took great interest in our home-made porta-ledges and weight tested them with us - i.e. bounced in them. He taught us how to overlock stitch the webbing for extra strength on the sewing machine.

We also had a tour of Mo’s, and his wife Jackie’s, Snowdon Mouldings factory, situated an old Welsh chapel on Strydd Goodman. There we each had made colourful fibreglass Joe Brown helmets. These famous lids were worn by every climber up until the late 80s when they were superseded by more lightweight plastic ones.

At that point, in the late 80s, I was lodging in Joe’s daughter, Zoe’s house. Joe would turn up every week to do maintenance on the rather dilapidated structure. During the week, Zoe, Ben Pritchard, Nick Harms, and I would try our damnedest to undo all the repairs Joe had made to the terraced house. We saw it as our prerogative. And, so that ‘Wonder Man’, ‘Baron Brown’, ‘The Human Fly’ would patiently return to repair the stair rail, the broken toilet or fix a hole in the roof.

Of course I knew of Joe’s rock climbs. Everybody did. I grew up in Manchester and caught the X10 bus to the Peak District every weekend. I had climbed The Right Unconquerable, Quietus, Avalanche Wall, the Curbar Cracks of Right Eliminate, Peapod, and Elder Crack, when I was a 16-year-old lad. Before the advent of modern gear these climbs were truly frightful ordeals. But, specialised rock climbing shoes and camming devices, had made them much safer propositions. They had become a right of passage for young climbers.

When I moved to Snowdonia, Cenotaph Corner, Suicide Wall, and his Cloggy (Clogwyn Du’r Arddu) climbs, Vember, Shrike, Woubits were legendary. Basically, if you opened any guidebook and found the best line the cliff, it was invariably, First Ascent - Joe Brown.

I was only vaguely conscious of Joe’s mountain exploits. As a teenager in Chamonix I had gazed up at the Fissure Brown and was aware of his record beating ascent of the Dru. Plus, I had borrowed Hamish Macinnes book, Climb To The Lost World about Joe and Don Whillans’ ascent of Mount Roraima from Bolton Library. But, up until then I had little interest in the mountains.

It was cool in the ‘80s around the Llanberis clique to consider Everest a snow-plod. In my mind this extended to any 8000m peak - I can only attribute my ignorance to the naivety of youth. So, at that time I was only dimly aware that Joe had made the first ascent of Kanchenjunga.

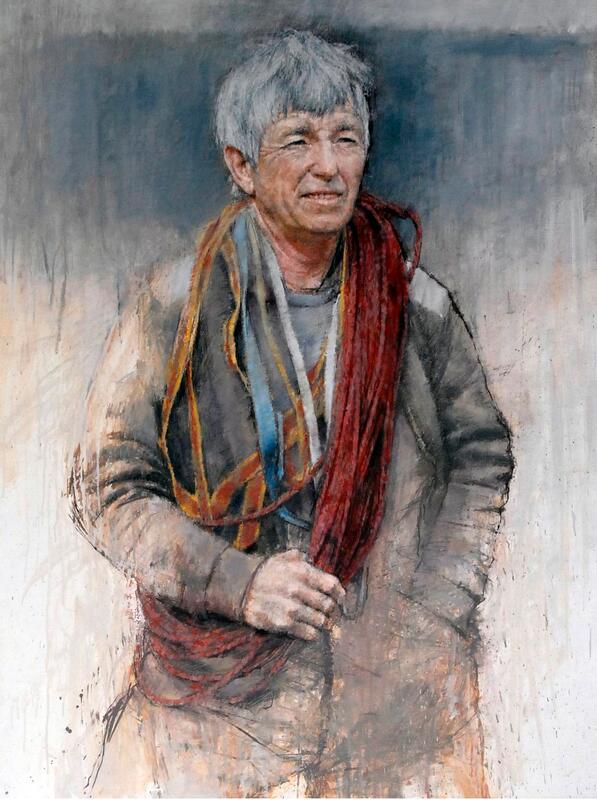

I grabbed a copy of Joe’s autobiography, The Hard Years, and flipped to the Kanchenjunga chapter. In those pages I learned he used a hand jam near the summit of the third highest mountain in the world to overcome a rock step. Why, legend has it that he invented the hand-jam. What was I thinking? This old bloke in brown chords and wooly jumper, holding a claw hammer, had made the first climb of the third highest mountain in the world!

One afternoon I was perusing a large shipment of rolling tobacco I had just received from our sponsor Imperial Tobacco. This being the 80s, we were all keen smokers and just wanted to bring a little bit of working-class Britain to the Himalayas. I was dividing the brown and yellow packets of Golden Virginia into five piles at the foot of Zoe’s stairs, when in walks Joe.

I was like a kid at Christmas showing his dad his new Tonka Truck. Gathering up my recently procured tobacco, I let the pouches fall through my hands, proudly saying, “Look Joe.”

He stood in the doorway and paused for a moment while his eyes became accustomed to the light.

“What have you got there?”

“Cigarettes. We’ve been sponsored by Imperial Tobacco.”

I had seen photographs of Joe smoking with Don Whillans so I naturally thought he would approve. “We’re going to be sorted for rollies.”

He looked at me with dismay in his eyes, “Well, I would give them up for a game of soldiers.”

And he stepped over me, wrench in hand. I felt about this big.

Being predominantly vegetarian the team also obtained sponsorship from a soy blancmange company, a peanut butter company, and received several hundred tubes of mushroom pâté. It may sound delicious but let me tell you after the ninetieth tube it isn’t. As you can see, I was all consumed in planning our first Himalayan expedition.

Then all our plans for Thalay Sagar began to wither. Mo got sick with cancer and rapidly went downhill. Joe understandably didn’t want to tackle such a committing trip without his mate. My guess is that he felt the weight of responsibility suddenly shift. Shortly before his death I vowed to Mo that we would go to the Himalaya. That the show would go on. The expedition did go ahead but the objective changed to the unclimbed West Face of Bhagirathi III in the same region (but that’s another story).

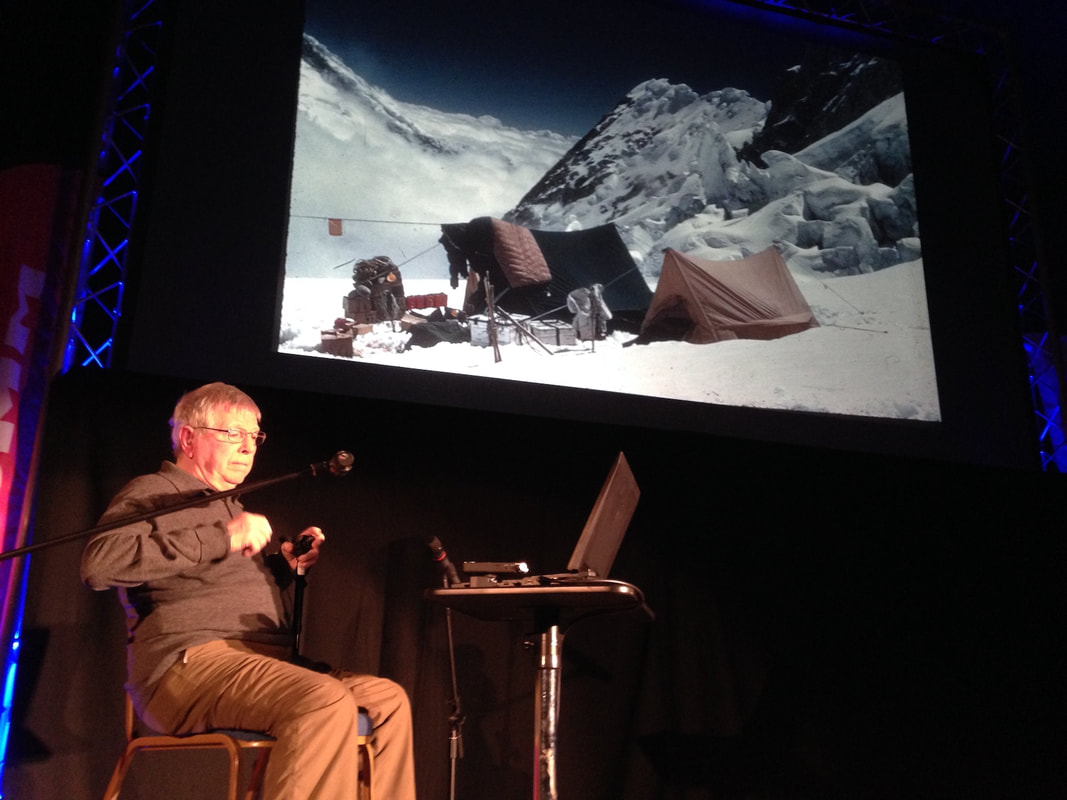

The last time I saw Joe he was delivering a slideshow he had presented previously at the Royal Geographical Society in London in 2005, for the fiftieth anniversary of the First Ascent of Kanchenjunga. This time however, it was the sixtieth anniversary and we were at Llanberis, a mountain festival of which he and I were patrons.

Joe was eighty-six but he enthralled the audience for over two hours with a passion that belied his years. The room was silent as Joe talked over slides of the long approach to Kanchenjunga. Distant images across acres of time.

Tony Streather and George Band - black specks on the Yalung Glacier.

A-frame tents and ammo boxes in the snow on "The Great Shelf" of the Yalung Face.

Tony Streather and George Band - black specks on the Yalung Glacier.

A-frame tents and ammo boxes in the snow on "The Great Shelf" of the Yalung Face.

High camps, all shot on grainy colour 35mm Kodak film stock.

None of these photos had been made public. Joe was still bound to the contract expedition leader Charles Evans had signed with the RGS sixty years earlier - handing over all photographic rights to the society.

And then, there it was… The famous slide of Joe hand-jamming his way up an overhanging crack on the West ridge of Kanchenjunga. This was in 1955 mind you, and well over 8000m.

Joe was the last climber standing from the Kanchenjunga Expedition. Scottish raconteur and mountain man, Tom Patey had the measure of one of the world’s great climbers in The Ballad of Joe Brown:

None of these photos had been made public. Joe was still bound to the contract expedition leader Charles Evans had signed with the RGS sixty years earlier - handing over all photographic rights to the society.

And then, there it was… The famous slide of Joe hand-jamming his way up an overhanging crack on the West ridge of Kanchenjunga. This was in 1955 mind you, and well over 8000m.

Joe was the last climber standing from the Kanchenjunga Expedition. Scottish raconteur and mountain man, Tom Patey had the measure of one of the world’s great climbers in The Ballad of Joe Brown:

He's like a human spider

Clinging to the wall--

Suction, faith and friction,

And nothing else at all;

But the secret of his success

Is his most amazing knack

Of hanging from a hand-jam

In an overhanging crack.

Clinging to the wall--

Suction, faith and friction,

And nothing else at all;

But the secret of his success

Is his most amazing knack

Of hanging from a hand-jam

In an overhanging crack.

“Old long-gone hand-jam Joe”

With information help from Eberhard Jurgalski at the Himalayan Database. Go to himalayandatabase.com for the most comprehensive information on the Nepal Himalaya.