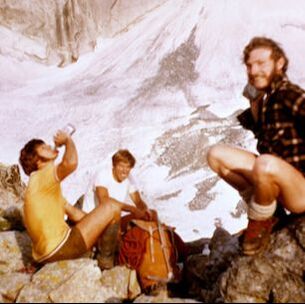

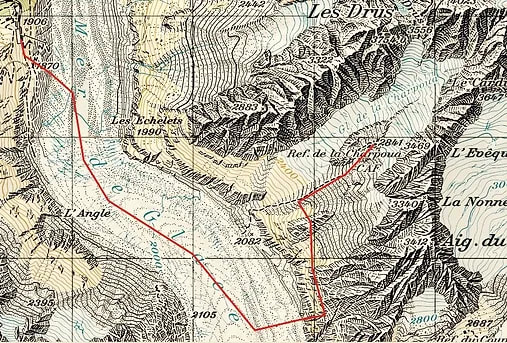

In 1971, four young Aussie friends go to Chamonix, France to climb the North Face of the Petit Dru (among other things). The Petit Dru is an 800-meter (2625-feet) mixed rock and ice climb. Keith Bell, John Fantini, Chris Baxter, and Howard Bevan pair up (Keith and John, Chris and Howard) and unknowingly enter into a no-holds-barred race to the top in this challenging terrain with 10+ other parties.

The friends end up losing track of each other while on the mountain and have two completely different experiences - each described here in Common Climber in a unique "tale of two climbs" stories. On this page, Keith Bell shares his experience in "Horses for Courses: The Dru Derby 1971" while Howard Bevan shares "My Dru Derby"

In a cool trifecta, we also have a copy of the original published account by Chris Baxter. In 1971 the story was published in Argus, the newsletter of the Victoria Climbing Climb of Mebourne, Australia, and Thrutch, an Austal-Asian climbing magazine. Read all three and experience the unique perspectives of each climber!

The friends end up losing track of each other while on the mountain and have two completely different experiences - each described here in Common Climber in a unique "tale of two climbs" stories. On this page, Keith Bell shares his experience in "Horses for Courses: The Dru Derby 1971" while Howard Bevan shares "My Dru Derby"

In a cool trifecta, we also have a copy of the original published account by Chris Baxter. In 1971 the story was published in Argus, the newsletter of the Victoria Climbing Climb of Mebourne, Australia, and Thrutch, an Austal-Asian climbing magazine. Read all three and experience the unique perspectives of each climber!

|

It was 3 p.m. on a fine and sunny day in the summer of ’71.

We had just checked into the "Dru Hilton" after making the arduous trek up from Montenvers. Four Aussies living the dream, treading on hallowed ground - ground that we had only read about in books. On arrival, with little else to do, we set about renovating some of the existing bivvy sites amid the rocks into comfortable and protected accommodations. We had just finished an early supper when we were visited by two Continental climbers. They asked us where we were from and learning we were Australian, immediately wrote us off. After all everyone knows Australia has no mountains, and therefore no mountaineers. We just smiled, shrugged and claimed ignorance of German, French, Italian, Spanish and admitted to only a spattering of halting English. It appeared that they had adopted the role of traffic cop for the Rognon’s occupants. Frustrated, they gave us our "designated" start time and set out in search of other parties to add to their starting grid. At 2:30 a.m. I was rudely awakened by the clanging and banging of pots and pans with John frantically trying to get us all up and moving. The Rognon and its surrounds was decorated like a Christmas tree with tiny lights flashing in all directions. An English rope went stomping past us, obviously not playing by the rules set down by our Continental friends. The air was alive with shouts that seemed to completely encircle us. Where did all these climbers come from? There must have been about 10 ropes all jockeying for position… and we were not even on the climb yet. |

We were right in the thick of things when we reached the snow slope that leads to the face. The scramble up the snow and the first couple of pitches on rock did not separate the first group of about six ropes In fact most of us were still climbing unroped and were spread all over the rock face.

When we reached the choke point, a chimney leading into a couloir, clearly the start of the climb proper, some organization was called for. The various ropes got sorted out and began stuffing themselves into the chimney. John and Keith had a slight lead but that only served as encouragement for the next few ropes to use their runners, which of course Keith removed as he passed them, leaving the leaders of the following ropes basically unprotected. You see some bizarre things in the Alps!

We had lost some ground while Chris figured out how to attach and remove his crampons. A heck of a time to find out that he had never climbed with them. An ice axe was, as far as Chris was concerned, a tool for making large cocktails.

We, however, were not without a plan. One of us would lead five pitches then the other would take the next five pitches. Clearly this had to be modified slightly so that I was to take the obvious snow/ice pitches while Chris took the dry and/or broken rock. Of course no plan is perfect and I managed to score the Fissure Lambert and the corner above - the best two pitch of rock climbing on the route.

For those unfamiliar with Alpine climbing, being first on a route can literally mean the difference between life and death. Of course, being the first to reach the summit and start your decent, the reverse is true. Earlier in the season Keith and I had to abandon our decent from the Grand Capucin and "holed up" under an overhang while a couple of Italian ropes charged down the couloir dislodging boulders the size of houses as they went — but that is a different story.

Having shed our crampons, we made up some ground, passing two ropes, which left one rope between us and the other half of our team, John and Keith.

I was climbing well, faster than I ever had and enjoying the exhilaration of being on a famous route. For the past two years I had relied on Keith to set the pace with me chuffing along behind.

When we reached the choke point, a chimney leading into a couloir, clearly the start of the climb proper, some organization was called for. The various ropes got sorted out and began stuffing themselves into the chimney. John and Keith had a slight lead but that only served as encouragement for the next few ropes to use their runners, which of course Keith removed as he passed them, leaving the leaders of the following ropes basically unprotected. You see some bizarre things in the Alps!

We had lost some ground while Chris figured out how to attach and remove his crampons. A heck of a time to find out that he had never climbed with them. An ice axe was, as far as Chris was concerned, a tool for making large cocktails.

We, however, were not without a plan. One of us would lead five pitches then the other would take the next five pitches. Clearly this had to be modified slightly so that I was to take the obvious snow/ice pitches while Chris took the dry and/or broken rock. Of course no plan is perfect and I managed to score the Fissure Lambert and the corner above - the best two pitch of rock climbing on the route.

For those unfamiliar with Alpine climbing, being first on a route can literally mean the difference between life and death. Of course, being the first to reach the summit and start your decent, the reverse is true. Earlier in the season Keith and I had to abandon our decent from the Grand Capucin and "holed up" under an overhang while a couple of Italian ropes charged down the couloir dislodging boulders the size of houses as they went — but that is a different story.

Having shed our crampons, we made up some ground, passing two ropes, which left one rope between us and the other half of our team, John and Keith.

I was climbing well, faster than I ever had and enjoying the exhilaration of being on a famous route. For the past two years I had relied on Keith to set the pace with me chuffing along behind.

The relative quiet of the early morning was broken by a shuffling and scraping drifting up from below. Our Continental friends from the night before had, unlike everyone else, stuck to their starting time and were now going to school us in the ways of a European mountaineer.

Lesson 1 - stay unroped for as long as possible.

Lesson 2 - if there is any chance of hitting snow, ice or verglas ahead, leave your crampons on.

Lesson 3 - use an ice axe that resembles a north wall hammer - one you can use like a butcher’s hook, thereby extending your reach by a foot or so.

The two Continentals zoomed past me with a tut-tut attitude and headed for the two leading ropes. We shared a stance or two with them, but above The Niche, still wearing their crampons, they pulled ahead, and we never saw them again.

Above the pitch following the Fissure Lambert, the climbing was unpleasant, steep, icy, and sustained. The crossing of The Niche signified the end of my five pitches. The lead parties were now out of sight above. A group of ropes were below us; we could hear them but not see them.

An English team bubbled up from below and shared a stance with me.

Lesson 1 - stay unroped for as long as possible.

Lesson 2 - if there is any chance of hitting snow, ice or verglas ahead, leave your crampons on.

Lesson 3 - use an ice axe that resembles a north wall hammer - one you can use like a butcher’s hook, thereby extending your reach by a foot or so.

The two Continentals zoomed past me with a tut-tut attitude and headed for the two leading ropes. We shared a stance or two with them, but above The Niche, still wearing their crampons, they pulled ahead, and we never saw them again.

Above the pitch following the Fissure Lambert, the climbing was unpleasant, steep, icy, and sustained. The crossing of The Niche signified the end of my five pitches. The lead parties were now out of sight above. A group of ropes were below us; we could hear them but not see them.

An English team bubbled up from below and shared a stance with me.

|

I introduced myself and was astounded that they knew my name. They had read an article in Mountain magazine about Australian climbing which featured my and Keith's ascent of Balls Pyramid. When they learned that Keith, who organized the Balls Pyramid trip, was up above us, they were even more interested in hearing about the climb. It turned out that this pair had just climbed the North Faces of the Eiger, Matterhorn, and Lyskamm! We were in rare company indeed.

Chris had knocked off his five pitches which left me with the crux of the climb. The Fissure Alain - a vertical crack system with an overhanging bulge about halfway up. The crack starts out as a fist jam, narrows to a hand jam, then below the bulge to fingertips only. The faces of the corner were smooth but there were a couple of pegs in the crack low down and one just over the bulge out of reach on the left face. When I reached the bulge, I came to a screeching halt. The crack was full of ice and I was two feet short of reaching the peg in the wall. I frigged about for a good five minutes but could not find the key to unlock the sequence. I suggested Chris should come up and try. He was nearly a foot taller than me, and I thought that may help, but he politely declined. The English rope got tired of waiting and found their own way up the left wall. This was not the usual crux bypass which we learned later, was further to the right and up a series of cracks – the Fissure Martinetti. Some impressive climbing by the Englishmen resulted in their reappearing above me and settling down on a small belay back on route. Since I was going nowhere and getting tired, I gave up trying to climb the bulge un-assisted and placed my smallest nut on the wall directly below the top peg and clipped in an etrier. I was in the process of stepping into it when my foot that was precariously placed on the crack rather than in it, slipped. I found myself dangling 30-feet down the pitch. Though stunned, I managed to get back on the rock, clip into a peg and take stock of my situation. I had landed on my face and my left knee. Blood was pouring out of my nose, and I had broken off one of my front teeth. There was also something wrong with my little finger - it looked like a banana. There was a three-inch gash under my left kneecap which was bleeding but not as profusely as my nose. More serious though, was that I could not bend my leg or put any weight on it. Nothing appeared to be broken but the left leg may as well have been. The immediate question was what to do next. The answer came like a missive from the heavens. One of the Englishmen was still on the stance above and he asked me if I wanted (or could use) a top rope. Are you kidding me? It was a life saver. A rope was tied off and I thrutched my way painfully up it on one leg and a single jumar. When I reached his stance, my benefactor took one look at me and was clearly concerned. |

In a display of bravado, I wiped the blood from my face, and with all the confidence I could muster told him that I would be alright, and he should climb on or he would be benighted. He scurried off. I brought Chris up but there was standing room only on the stance so the triage would have to wait.

There was very little discussion. Retreat was not an option, and a possible rescue would be easier the higher we went. It was onward and upward then.

The topo indicated there were six pitches left, varying in difficulty from Alpine IV- to V+. Added to the grades, was the higher we climbed, the heavier the verglas.

There was very little discussion. Retreat was not an option, and a possible rescue would be easier the higher we went. It was onward and upward then.

The topo indicated there were six pitches left, varying in difficulty from Alpine IV- to V+. Added to the grades, was the higher we climbed, the heavier the verglas.

|

At one point the English team yelled down that the going was getting easier, and this revived our spirits. But it was getting late, and the sun was hitting the upper part of the face. Now the chimneys were not just slippery, but some were running with water. Knowing we would be spending the night out; we took off our jumpers and donned our parkas.

We finally reached a small ice field only two or three pitches from the summit. Chris led up it but zigged right when he should have zagged left. Realizing his error, he crossed back left towards a crowded stance. Just as he reached the rock Chris lost a crampon. What else could go wrong? The time taken by Chris in the snow field had allowed us to be caught by not one, but two British ropes. A leader, a belayer, and Chris all trying to share a stance the size of a dinner plate. In his account of the ascent Chris wrote: |

The sun had just dived below the horizon and in desperation I clawed up the British belayer using a sling on his anchor-peg, stood on his rope and fought past, nearly falling into his open mouth.“

Chris was starting to get the hang of this alpine climbing thing! He forged on.

I had been very lucky. Most of the climbing since my fall had been vertical, with very little traversing. This meant Chris could give me a tight rope where I needed it.

Not so the final pitch for the day - a long traverse to the right, up easier ground, then around a corner to the Quartz Ledge – our bivvy site for the night. I finally plopped onto it completely exhausted.

Chris was also pretty tired. All we could muster was a couple of brews and a Mars bar each before trying to sleep. We did not have sleeping bags or mats, so it was duvets and wet britches with boots off inside a nylon bivvy bag on bare rock for us.

The night seemed endless, but sitting atop the Bonatti Pillar had its diversions. The lights of Chamonix were directly below us, twinkling in syncopated rhythm with our shivering. Every now and again thin clouds riding invisible zephyrs turned the valley’s lights off only to have them slowly return to their former glory as the clouds scudded on. In short, a long cold night with little sleep - a typical alpine bivouac.

I had been very lucky. Most of the climbing since my fall had been vertical, with very little traversing. This meant Chris could give me a tight rope where I needed it.

Not so the final pitch for the day - a long traverse to the right, up easier ground, then around a corner to the Quartz Ledge – our bivvy site for the night. I finally plopped onto it completely exhausted.

Chris was also pretty tired. All we could muster was a couple of brews and a Mars bar each before trying to sleep. We did not have sleeping bags or mats, so it was duvets and wet britches with boots off inside a nylon bivvy bag on bare rock for us.

The night seemed endless, but sitting atop the Bonatti Pillar had its diversions. The lights of Chamonix were directly below us, twinkling in syncopated rhythm with our shivering. Every now and again thin clouds riding invisible zephyrs turned the valley’s lights off only to have them slowly return to their former glory as the clouds scudded on. In short, a long cold night with little sleep - a typical alpine bivouac.

|

In the morning, no matter how hard I tried, I could not get my boots on. My leg had stiffened and was now completely immobile. With Chris’s help I finally got shod and prepared myself for the day’s activities.

Starting with a long traverse followed by eight abseils then “easy” down climbing and finally traversing a heavily crevassed glacier. With the exception of the abseiling, all this appeared to need two legs to accomplish. None of it looked inviting, but all of it had to be done. I perked up a bit when I saw the two British groups that Chris had "met" the afternoon before. They were setting up the first of eight abseils necessary to escape the Dru. I have no memory of these abseils other than there were now six in the party to help with my descent. At the bottom of the abseils the Brits took off along the base of the Flammes de Pierre heading for Montenvers, while we dropped down and crossed the Chapoua Glacier - an icy moat guarding the Chapoua hut. |

The glacier was heavily crevassed and jumping even the small ones was out of the question for me. We had to take the long way around each and every one. It was torture.

It was mid-afternoon when we finally reached the hut, and I could go no further. As a final indignity, we did not have enough money to pay for the night’s accommodation. The custodian however took one look at me and opened the door to us. He even fed us and gave me some codeine which allowed me to sleep and recuperate. I will forever be in his debt.

The next day dawned fine and warm. I had yet to figure out the best mode of descent down the steep, rocky track to the Mer de Glace. I tried facing downhill, uphill, and sideways, but all caused great pain. Desperate conditions call for desperate solutions.

At one point I sat down, faced uphill and slithered backwards on my bum dragging my useless leg down with me. Fortunately, my serge britches were almost bomb proof with a reinforced rear end for good measure. They survived the indignity without complaint.

After a couple of hours of slithering we stopped for a rest and some water. Upon looking down the slope I could see several individuals making their way up the scree towards us. Keith and Mike, a non-climbing friend of Chris’, along with, of all things, a nurse, were coming to my rescue, and I was bloody glad to see them. It appeared that the two Brits who had helped me directly after my fall had found Keith and Mike in the valley campsite and informed them of our plight.

Not stopping at simply raising the alarm, a friend of theirs, a British nurse (who’s name regrettably I do not recall), offered to accompany Keith and Mike up the hill and render assistance. Render she did. The wound was cleaned and the knee wrapped with about half a mile of adhesive bandage. The support this gave to my leg was magical.

It was mid-afternoon when we finally reached the hut, and I could go no further. As a final indignity, we did not have enough money to pay for the night’s accommodation. The custodian however took one look at me and opened the door to us. He even fed us and gave me some codeine which allowed me to sleep and recuperate. I will forever be in his debt.

The next day dawned fine and warm. I had yet to figure out the best mode of descent down the steep, rocky track to the Mer de Glace. I tried facing downhill, uphill, and sideways, but all caused great pain. Desperate conditions call for desperate solutions.

At one point I sat down, faced uphill and slithered backwards on my bum dragging my useless leg down with me. Fortunately, my serge britches were almost bomb proof with a reinforced rear end for good measure. They survived the indignity without complaint.

After a couple of hours of slithering we stopped for a rest and some water. Upon looking down the slope I could see several individuals making their way up the scree towards us. Keith and Mike, a non-climbing friend of Chris’, along with, of all things, a nurse, were coming to my rescue, and I was bloody glad to see them. It appeared that the two Brits who had helped me directly after my fall had found Keith and Mike in the valley campsite and informed them of our plight.

Not stopping at simply raising the alarm, a friend of theirs, a British nurse (who’s name regrettably I do not recall), offered to accompany Keith and Mike up the hill and render assistance. Render she did. The wound was cleaned and the knee wrapped with about half a mile of adhesive bandage. The support this gave to my leg was magical.

Now, with Keith and Mike carrying my pack (Chris had already taken the heavy items from me) and taking turns to support my left side, I was able to hobble down the scree to the Mer de Glace. When we reached the flatter, smoother glacier, I felt like I was running. Well, not quite running, more like Pirate Pete swinging his stump. The others had difficulty keeping up. Of course, I may have been delirious and just imagining this.

The final obstacle – the ladders from the glacier leading up to Montenvers Station – could not slow me down.

Keith and Mike magnanimously proffered their return tickets on the railway so Chris and I could ride the last few kilometers into Chamonix in style.

What followed for me was a visit to the hospital where I was given the choice of a full leg cast or a tensor bandage to take care of the cracked knee cap. I chose the bandage solution - after all I had more climbing to do. This was followed by a trip to the dentist. Now that was frustrating. We could find no one who would admit to speaking English - and since there is not a great need to speak French in Australia, I had never learned how. In the end the dentist troweled on some cement to seal the tooth and called it done. When I got to London a couple of months later, I had the tooth yanked.

Lesson learned.

Following this experience I made it a priority to learn a spattering of the local language. Sherpa, Nepali, Swahili, Spanish and Quechua were all abused in the following years.

The final obstacle – the ladders from the glacier leading up to Montenvers Station – could not slow me down.

Keith and Mike magnanimously proffered their return tickets on the railway so Chris and I could ride the last few kilometers into Chamonix in style.

What followed for me was a visit to the hospital where I was given the choice of a full leg cast or a tensor bandage to take care of the cracked knee cap. I chose the bandage solution - after all I had more climbing to do. This was followed by a trip to the dentist. Now that was frustrating. We could find no one who would admit to speaking English - and since there is not a great need to speak French in Australia, I had never learned how. In the end the dentist troweled on some cement to seal the tooth and called it done. When I got to London a couple of months later, I had the tooth yanked.

Lesson learned.

Following this experience I made it a priority to learn a spattering of the local language. Sherpa, Nepali, Swahili, Spanish and Quechua were all abused in the following years.