“Karen! I am going to fall!" I yelled. She exclaimed panic and I blubbered back, “Pull in some rope!” With both hands, she pulled the rope through the quick draw, letting go on the belay-side of the 8-Ring. I, with my fingertips now beyond the point of liquid fire, calmly asked her to pull the rope through the 8 Ring. Then, with my last burn of my tips I asked her to grab the rope behind the 8 Ring with both hands - putting the metal 8 Ring between what was soon to be a max loaded anchor carabiner and her hands. With Karen ready, I gave myself up for the ride. There are ways to slide in a stable manner on granite slab, including one called surfing, like Captain Granitic in those old cartoons. That's what I did..

If you've climbed long enough, you begin to learn a few rules about falling - like short falls can sometimes be worse than that nice ride to a more natural outcome, it's good to fall where there is nothing to hit, the art of the catch starts with communication, and practicing falls might just save your ass. After witnessing, belaying, and taking many falls over my years of climbing, I have developed a few rules - the first rule being:

Sometimes if you have some distance to fall, it can be good. (Of course, there is an exception to this which I discuss next in rule #2...)

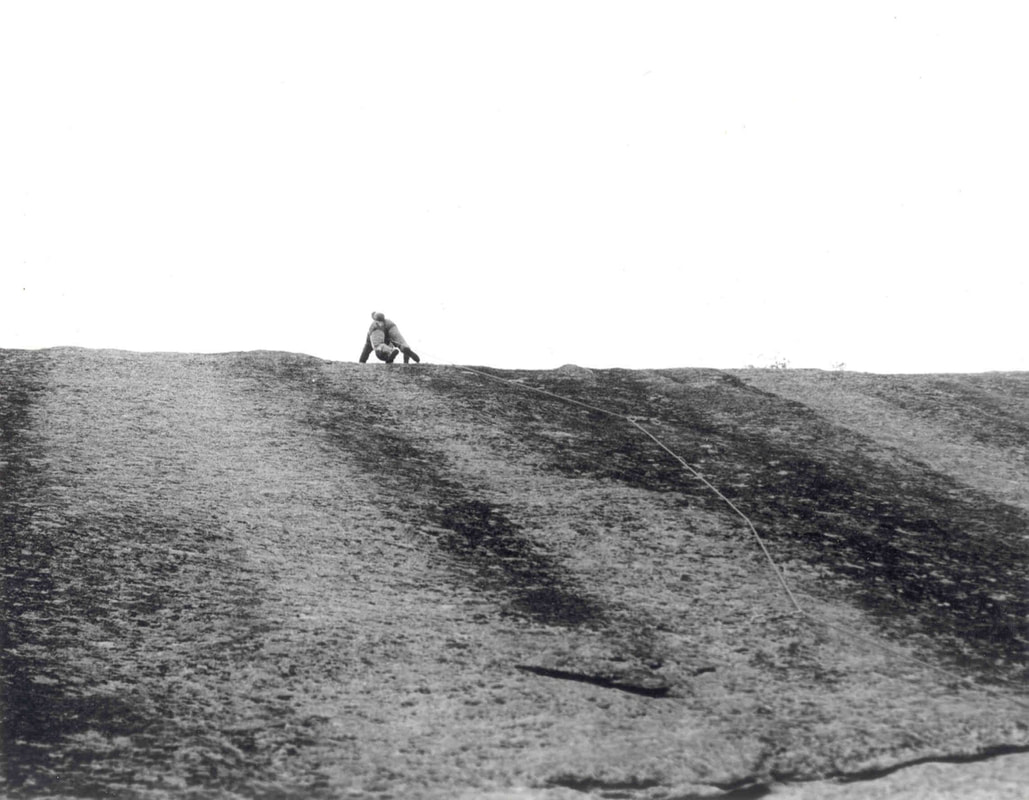

The best example of I ever saw of rule number 1 was Hank Caylor trying for an early send of Real Gravy on the back side of Enchanted Rock, located a couple hours outside of Austin, Texas. Back in the day, the route only had three bolts and fueled a controversial Oklahoma-Texas rivalry feud!

Hank, at the ripe young age of fifteen, was about 25 feet into the big 80-foot R-X run out after the third bolt, heading to the bolt on the climb Rites of Spring. He was in the steep part of the thin stuff, 5.11 moves, and still about 10 feet from where the angle kicks back to provide some relief. At this point, Hank was looking at a fifty-footer - what falls off Real Gravy used to be called.

In this section of the climb, it's really thin, consisting of little lichen covered edges, crystals and knobs, and not nearly enough of them. It’s steep and the wealth of features is like hope in an arid desert when you've run out of water. It's sustained micro moves, little thing to little thing, no happy holds, just tiny, sequential moves to stances with time limits. Nerves. Stressfully, neurotically, desperately sustained small holds to smaller holds.

And then, the shit hit the fan. Hank lost his spider stance and looked at almost eight fathoms of air before he felt the life-saving catch of the rope. But in those first seconds of the fall, Hank slightly pushed himself away from the wall and was then flying free.

In the time he was given, Hank gathered himself into a left side down-ball, with his right hand on the rope and his left protecting his head and upper body. He rotated so that his feet were in a compact squat facing the wall, fending his body from the impending impact. He looked like a rodeo cowboy attached to a rope.

Hank flew straight down, parallel to the face, with but a foot or two of space between him and the rock. This went on for what seemed like forever, until his rope, clipped into the original third bolt - a poorly placed 1/4-inch split rivet - became taut and caught him. Doiingg...

He rode air through to the initial catch and absorbed rope stretch. And, as calmly as a falling cat, Hank simply landed with his feet against the wall, dissipating the force of the fall and maintaining control. There was much ooh-ing, awe-ing, and cackling. Hank then remounted the route and sent it. I think it was the third ascent.

In my experience, bolts should have enough space and air around them so when that fall happens you have a handful of milliseconds to react, sense, orient, and prepare for earth contact - where feet and hands and body position are optimal, versus the awkward short-rope jerk and slap.

My, perhaps old school, theory? Run outs are good for you!

If you've climbed long enough, you begin to learn a few rules about falling - like short falls can sometimes be worse than that nice ride to a more natural outcome, it's good to fall where there is nothing to hit, the art of the catch starts with communication, and practicing falls might just save your ass. After witnessing, belaying, and taking many falls over my years of climbing, I have developed a few rules - the first rule being:

Sometimes if you have some distance to fall, it can be good. (Of course, there is an exception to this which I discuss next in rule #2...)

The best example of I ever saw of rule number 1 was Hank Caylor trying for an early send of Real Gravy on the back side of Enchanted Rock, located a couple hours outside of Austin, Texas. Back in the day, the route only had three bolts and fueled a controversial Oklahoma-Texas rivalry feud!

Hank, at the ripe young age of fifteen, was about 25 feet into the big 80-foot R-X run out after the third bolt, heading to the bolt on the climb Rites of Spring. He was in the steep part of the thin stuff, 5.11 moves, and still about 10 feet from where the angle kicks back to provide some relief. At this point, Hank was looking at a fifty-footer - what falls off Real Gravy used to be called.

In this section of the climb, it's really thin, consisting of little lichen covered edges, crystals and knobs, and not nearly enough of them. It’s steep and the wealth of features is like hope in an arid desert when you've run out of water. It's sustained micro moves, little thing to little thing, no happy holds, just tiny, sequential moves to stances with time limits. Nerves. Stressfully, neurotically, desperately sustained small holds to smaller holds.

And then, the shit hit the fan. Hank lost his spider stance and looked at almost eight fathoms of air before he felt the life-saving catch of the rope. But in those first seconds of the fall, Hank slightly pushed himself away from the wall and was then flying free.

In the time he was given, Hank gathered himself into a left side down-ball, with his right hand on the rope and his left protecting his head and upper body. He rotated so that his feet were in a compact squat facing the wall, fending his body from the impending impact. He looked like a rodeo cowboy attached to a rope.

Hank flew straight down, parallel to the face, with but a foot or two of space between him and the rock. This went on for what seemed like forever, until his rope, clipped into the original third bolt - a poorly placed 1/4-inch split rivet - became taut and caught him. Doiingg...

He rode air through to the initial catch and absorbed rope stretch. And, as calmly as a falling cat, Hank simply landed with his feet against the wall, dissipating the force of the fall and maintaining control. There was much ooh-ing, awe-ing, and cackling. Hank then remounted the route and sent it. I think it was the third ascent.

In my experience, bolts should have enough space and air around them so when that fall happens you have a handful of milliseconds to react, sense, orient, and prepare for earth contact - where feet and hands and body position are optimal, versus the awkward short-rope jerk and slap.

My, perhaps old school, theory? Run outs are good for you!

Hank displayed the perfect example of Rule #1: Sometimes if you have some distance to fall, it can be good, but of course, there is an exception to this, and that is Rule #2...

Rule #2. It’s good to fall when there is nothing to hit.

So, after some other big falls and a couple broken legs on Real Gravy, we have since added three bolts after the massively runout third bolt described above. The Central Texas Climbing Committee (CTCC) - the first-ever elected representative climbing advisory committee in the US, who advise the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department - decided the 80-foot run out was a bit excessive and authorized the addition of the bolts and the replacement of all the original quarter inch split rivets. With three bolts in 80 feet, there's still some distance to make body corrections in a fall and now it also follows Rule #2.

Another great Rule #2 story stashed in the memory banks is when Mike “Mikie” Head ripped out a 25-foot section of A5 hooks and heads when we did the 16th ascent of the Pacific Ocean Wall of El Capitan back in 1981.

It was our day’s first A5 pitch after fixing the first five pitches. There are always belay chores on a big wall - stacking ropes, undoing clusterfucks with the haul lines, and sorting the belay. There is a lot of baggage and shit hanging at the belay - three haul pigs, hand hauls, ropes, and a jug line for Dave Baltz, who was cleaning the previous pitch. As I sorted out the nest with one hand, my left was faithfully on Mikie’s belay, behind my shop-crafted steel belay plate.

|

Mikie was on our team's newest rope, a nice 11mm Mammut dynamic that was my wife, Karen’s Christmas gift to me. Good ropes are important when your ass is hanging in a couple thousand feet of pure air. We called this Big Al’s Air Show - where just looking down is a mind-loosening vent in steep space. On El Cap it's so steep and huge, you actually climb through a parallax, where your eyes lose definition of ground-relative depths. Hundred-foot tall pine trees look like shrubs because your eyes can no longer resolve their height in the expanse of big air. This parallax has to do with how far apart your eye balls are and the granularity of your brain’s optical interpretation. Everyone is different and it’s fun to find your personal parallax.

So, anyway, that day Mikie rode some big air. He ripped out about 30-feet of natty-aid-mank, and had time to align himself in space to give me a kick and a howler as he flew by, yelling, “Pull in some rope asshole!” I panic-reacted to Mikie's flyby. All I could do was yank hard with my left hand. I watched the slackened rope snap tight. My eyes also focused on the Forrest Foxhead nut that Mike had placed as his first piece of the pitch. It was a bomber placement with a Clog D carabiner clipped to the rope, which was located eye level to me. The rope snapped taught and then the carabiner on the Foxhead exploded, with fragments flying into space! The rope whipped across my lap, pinned my right forearm, and direct-loaded the full arresting forces for the fall onto my belay plate, my left hand, and my pinned right forearm. As the shock load forces grew while absorbing the de-acceleration of Mikie, the stretching caused a contraction in rope diameter. The shrinking diameter then reduced the belay plate’s holding power, causing the rope to slip through the plate and my fingers, making a bloody groove across my forearm...but Mikie? He had this 60 foot free-fall into space with nothing to hit - except to give me a kick as he flew by - ultimately bouncing carefree in the air. |

If rules #1 and #2 are more about the nature of the fall, then the next two rules are about the preparation.

Rule #3 focuses on the communication between the belayer and the climber. To enable the belayer’s success, the art of the catch is how not to be surprised at the surprise party!

Then there is Rule #4, which is to actually know how to fall in specific circumstances.

Many falls are a surprise event, but even then, preparation can go a long way towards a good outcome. But, there are also those long, drawn out epics of fail that lead up to a fall. You know those, where fingertips melt, grips ultimately fail, and the fear grows as your fate is known in advance. During these times, the belayer and climber generally know the event is forthcoming and have probably had a multi-syllabolic dialog with each other. Panic? This scenario could build up to it, or it could help both the belayer and climber be prepared.

Ultimately, preflight management is about avoiding a painful outcome when airtime is certain.

I am reminded of one of my biggest rides. I was newly married, and Karen, my beautiful, petite, 60-pound-lighter belayer-wife, (I was skinny back then!) were on a Colorado climbing honeymoon. After a tour from Crested Butte, to Devils Tower, to Boulder, Colorado we ended our party on some Pikes Peak granite and some nice high camping.

Before heading up there, my dear friend Steve "Muff” Cheney told me tales of Old Ironsides up in The Crags on the west side of Pikes Peak. As he buffed my boots with fresh Brand X rubber, Muff talked about a couple of routes he thought I might be interested in - Excitable Boy and, with a chuckle, Keel Hauled. Muff's smile suggested a bit of a challenge for an excitable boy like me. I was hooked, but perhaps I should have considered the climb's name in this little challenge. (Being keel hauled refers to a punishment done by the old Dutch navy where an offender was tied to a rope, plunged into the water on one side of the ship, then pulled across the keel and upside the other side of the ship.)

Old Ironsides is a perfect two-pitch slab wall of pure Pikes Peak granite - nothing but thinness, smears and edges. Karen and I did and enjoyed Excitable Boy, a spicy 5.10, and it made me want to sniff out the 5.11 runout monster Muff mentioned... Keel Hauled.

Excitable Boy and Keel Hauled actually share a belay at the top of the first pitch (a 150-foot runout unprotected 5.8 slab). So after finishing Excitable Boy, Karen and I reestablished ourselves at the belay for Keel Hauled, which launches out right into a sea of slab to a bolt 50 feet away. I set Karen up at the two-bolt belay with deer-skin gloves and an 8 Ring clipped like a stitch through the small hole for belay. I clipped a quick draw on the right-hand bolt and ran my lead line through it.

Soon I was 40 feet out, level with the next bolt, but still needing to traverse right to get to it. I was looking at an 80-footer if I blew it.

It was sketchy thin and my fingertips and calves were burning. The whole time I was running a dialog of neurotic chatter with dearest Karen. Her stress level increased in tune with my panic. I started to traverse to the bolt, but crunchy crumbles of lichen in my marginal smears caused my finger tips to start to shred and melt. My ability to hold on deteriorated and I realized I was going to take the ride.

I was going to be Keel Hauled!

“Karen! I am going to fall!" I yelled.

She exclaimed panic and I blubbered back, “Pull in some rope!” With both hands, she pulled the rope through the quick draw, letting go on the belay-side of the 8-Ring.

I, with my fingertips now beyond the point of liquid fire, calmly asked her to pull the rope through the 8 Ring. Then, with my last burn of my tips I asked her to grab the rope behind the 8 Ring with both hands - putting the metal 8 Ring between what was soon to be a max loaded anchor carabiner and her hands. With Karen ready, I gave myself up for the ride.

Now, there are actually ways to slide in a stable manner on granite slab, including one called surfing, like Captain Granitic in those old cartoons. That's what I did. I slid on the front flats of my boot soles, heels low and finger tips out brushing the rock. One hand was high protecting my face and head, and the other shoulder height controlling rotation and body position, keeping me on and above my feet. Correspondingly my opposite foot slid the lowest, and my higher foot was slightly out for stability.

This gave me four points of contact with the slab of rock as I slid, and the ability to stabilize any rotations. My low heels and smooth soles glided over bumps as my other three points of contact stabilized me. Of course, all this happens in a flash, so surfing is something slab climbers practice - Devils Slide at Enchanted Rock is a perfect practice ground.

I also had a 20 foot displacement to the right of Karen and 45+ feet of rope between me and the belay, so I was going to have a big swing at the end. This fact set my millisecond decision for my right foot to be lower and my higher foot on my “Karen-side” left.

I surfed until the rope went taut. It grabbed me and yanked me left. I then rose out of my surf stance and onto my left foot and I began to run!

My running steps became monster 15-foot, lengthening strides. I tried not to over rotate and faceplant. All the momentum and speed generated in my slide were now translated into swinging rotation. I struggled to make my strides fly far enough so as to not slap my face into the granite. It’s like a terrifying Olympic long jump, where all you do is get ready to jump!

I couldn't hear my own screams over Karen’s shrieks of terror as she was slammed against the quick draw on the right-hand bolt. The 8-Ring took the brunt of the collision as my slide consumed the slack out of the system. Karen caught a big one - like big game fishing!

The end result was sore feet, sore tips, and a traumatized wife - but we were prepared. Of course there was my embarrassment at having to retreat and tell Muff the whole story back in town. Yep. Karen and I had just become another one of his tales of those who have been Keel Hauled!

Rule #3 focuses on the communication between the belayer and the climber. To enable the belayer’s success, the art of the catch is how not to be surprised at the surprise party!

Then there is Rule #4, which is to actually know how to fall in specific circumstances.

Many falls are a surprise event, but even then, preparation can go a long way towards a good outcome. But, there are also those long, drawn out epics of fail that lead up to a fall. You know those, where fingertips melt, grips ultimately fail, and the fear grows as your fate is known in advance. During these times, the belayer and climber generally know the event is forthcoming and have probably had a multi-syllabolic dialog with each other. Panic? This scenario could build up to it, or it could help both the belayer and climber be prepared.

Ultimately, preflight management is about avoiding a painful outcome when airtime is certain.

I am reminded of one of my biggest rides. I was newly married, and Karen, my beautiful, petite, 60-pound-lighter belayer-wife, (I was skinny back then!) were on a Colorado climbing honeymoon. After a tour from Crested Butte, to Devils Tower, to Boulder, Colorado we ended our party on some Pikes Peak granite and some nice high camping.

Before heading up there, my dear friend Steve "Muff” Cheney told me tales of Old Ironsides up in The Crags on the west side of Pikes Peak. As he buffed my boots with fresh Brand X rubber, Muff talked about a couple of routes he thought I might be interested in - Excitable Boy and, with a chuckle, Keel Hauled. Muff's smile suggested a bit of a challenge for an excitable boy like me. I was hooked, but perhaps I should have considered the climb's name in this little challenge. (Being keel hauled refers to a punishment done by the old Dutch navy where an offender was tied to a rope, plunged into the water on one side of the ship, then pulled across the keel and upside the other side of the ship.)

Old Ironsides is a perfect two-pitch slab wall of pure Pikes Peak granite - nothing but thinness, smears and edges. Karen and I did and enjoyed Excitable Boy, a spicy 5.10, and it made me want to sniff out the 5.11 runout monster Muff mentioned... Keel Hauled.

Excitable Boy and Keel Hauled actually share a belay at the top of the first pitch (a 150-foot runout unprotected 5.8 slab). So after finishing Excitable Boy, Karen and I reestablished ourselves at the belay for Keel Hauled, which launches out right into a sea of slab to a bolt 50 feet away. I set Karen up at the two-bolt belay with deer-skin gloves and an 8 Ring clipped like a stitch through the small hole for belay. I clipped a quick draw on the right-hand bolt and ran my lead line through it.

Soon I was 40 feet out, level with the next bolt, but still needing to traverse right to get to it. I was looking at an 80-footer if I blew it.

It was sketchy thin and my fingertips and calves were burning. The whole time I was running a dialog of neurotic chatter with dearest Karen. Her stress level increased in tune with my panic. I started to traverse to the bolt, but crunchy crumbles of lichen in my marginal smears caused my finger tips to start to shred and melt. My ability to hold on deteriorated and I realized I was going to take the ride.

I was going to be Keel Hauled!

“Karen! I am going to fall!" I yelled.

She exclaimed panic and I blubbered back, “Pull in some rope!” With both hands, she pulled the rope through the quick draw, letting go on the belay-side of the 8-Ring.

I, with my fingertips now beyond the point of liquid fire, calmly asked her to pull the rope through the 8 Ring. Then, with my last burn of my tips I asked her to grab the rope behind the 8 Ring with both hands - putting the metal 8 Ring between what was soon to be a max loaded anchor carabiner and her hands. With Karen ready, I gave myself up for the ride.

Now, there are actually ways to slide in a stable manner on granite slab, including one called surfing, like Captain Granitic in those old cartoons. That's what I did. I slid on the front flats of my boot soles, heels low and finger tips out brushing the rock. One hand was high protecting my face and head, and the other shoulder height controlling rotation and body position, keeping me on and above my feet. Correspondingly my opposite foot slid the lowest, and my higher foot was slightly out for stability.

This gave me four points of contact with the slab of rock as I slid, and the ability to stabilize any rotations. My low heels and smooth soles glided over bumps as my other three points of contact stabilized me. Of course, all this happens in a flash, so surfing is something slab climbers practice - Devils Slide at Enchanted Rock is a perfect practice ground.

I also had a 20 foot displacement to the right of Karen and 45+ feet of rope between me and the belay, so I was going to have a big swing at the end. This fact set my millisecond decision for my right foot to be lower and my higher foot on my “Karen-side” left.

I surfed until the rope went taut. It grabbed me and yanked me left. I then rose out of my surf stance and onto my left foot and I began to run!

My running steps became monster 15-foot, lengthening strides. I tried not to over rotate and faceplant. All the momentum and speed generated in my slide were now translated into swinging rotation. I struggled to make my strides fly far enough so as to not slap my face into the granite. It’s like a terrifying Olympic long jump, where all you do is get ready to jump!

I couldn't hear my own screams over Karen’s shrieks of terror as she was slammed against the quick draw on the right-hand bolt. The 8-Ring took the brunt of the collision as my slide consumed the slack out of the system. Karen caught a big one - like big game fishing!

The end result was sore feet, sore tips, and a traumatized wife - but we were prepared. Of course there was my embarrassment at having to retreat and tell Muff the whole story back in town. Yep. Karen and I had just become another one of his tales of those who have been Keel Hauled!