Rock Climbing is a conduit to the present moment. An orchestration of effort, breath, focus, quieting the mind, eradicating doubt, bowing tension, feeling tiny nuances in the rock with your fingertips, and strategically dancing your feet across pockets and protrusions on the rock face. Finding the balance between grit and grace.”

-– Clayton Weakley

This quote, from a good friend and fellow climber and coach, was one of the most poetic and spot-on definitions of rock climbing I have ever heard. Especially the last sentence. Achieving the perfect balance between grit and grace is the “zone” where climbers put on their best show. I interpret grit and grace as the full expression of one’s physical and mental strength through the surgical precision and control of one’s mind and body.

How does one achieve such a balance? I believe the answer can be found through a better understanding studying mobility training in this medium and the perspective I would like you to adopt. One can be thoroughly strong and still struggle on the wall via lack of technique, which causes inefficient use of energy. One can be thoroughly technical but will eventually struggle to push new grades because of their inability to accommodate the increase in physical difficulty.

Mobility training is the study, practice, and training of grit and grace. It is how we improve our strength while effectively applying the strength specifically through enhanced body control. There is no question that rock climbing is both physically intense and favors those who delicately dance up the wall. While actually getting to the rock gym and climbing outside is a fantastic way to improve your strength and skill, there is a lot of training that can be done "off-the-wall" that can drastically improve the physical elements you bring to your climbing sessions.

How does one achieve such a balance? I believe the answer can be found through a better understanding studying mobility training in this medium and the perspective I would like you to adopt. One can be thoroughly strong and still struggle on the wall via lack of technique, which causes inefficient use of energy. One can be thoroughly technical but will eventually struggle to push new grades because of their inability to accommodate the increase in physical difficulty.

Mobility training is the study, practice, and training of grit and grace. It is how we improve our strength while effectively applying the strength specifically through enhanced body control. There is no question that rock climbing is both physically intense and favors those who delicately dance up the wall. While actually getting to the rock gym and climbing outside is a fantastic way to improve your strength and skill, there is a lot of training that can be done "off-the-wall" that can drastically improve the physical elements you bring to your climbing sessions.

Mobility = Movement Freedom

I don’t need more strength, more resilience to injury, or more beta options for this climb.”

– Said No Climber Ever

When you improve your mobility, you improve your movement freedom. You open new doors of movement that were previously closed due to physical limitations.

- Imagine finally being able to be comfortable and confident in that awkward stemming position.

- Imagine that splits stance on the wall that doesn’t over-stress your hips or groins to potential injury.

- Imagine being able to use that higher foot that would make the next hand hold light years closer to use rather than attempt a low percentage dyno or deadpoint move.

|

When you improve your USABLE range of motion, you improve your ability to problem solve the climb more effectively because you have more options, plain and simple. Let’s quickly review what I mean by “USABLE” range of motion: (refer to my previous article Rock Climber Mobility for more detailed information) USABLE Range of motion (i.e. mobility) is the range of motion that we can ACTIVELY use, give effort in, produce force in, and have complete movement control over. |

USELESS Range of motion (i.e. flexibility) is the range of motion that the body can be PASSIVELY placed into but is not strong and is uncontrollable. Once you get into this position you are “stuck."

Now, flexibility is not completely “useless”. It is the prerequisite to “usable” mobility. It’s within that transition process where we acquire more grit and grace - it shows us where we need to attain strength.

The Hip

Movement about the hip revolves around how the femoral head (ball of thigh bone) interacts with the acetabulum of the pelvis (hip socket.) It is one of the ball-and-socket joints of the body and therefore has a lot of range of motion to offer! The hip has six general movements: flexion, extension, adduction, abduction, internal rotation, and external rotation. You will see these motions in clear visuals when we get to the assessment section below.

“How much range of motion is good?”

This is a common question asked by many. Although doctors and therapists can quickly refer to research about the “norms” of hip range of motion, it may unfairly categorize you. Chances are the research was not done on rock climbers and does not consider what YOU need for YOUR life and activities. We are too individual to be generalized. There are things we can change and there are things we cannot change. We can certainly improve ourselves but the ceiling will always be limited by the individualizing and unchangeable elements of our body. Let’s look at a few:

“How much range of motion is good?”

This is a common question asked by many. Although doctors and therapists can quickly refer to research about the “norms” of hip range of motion, it may unfairly categorize you. Chances are the research was not done on rock climbers and does not consider what YOU need for YOUR life and activities. We are too individual to be generalized. There are things we can change and there are things we cannot change. We can certainly improve ourselves but the ceiling will always be limited by the individualizing and unchangeable elements of our body. Let’s look at a few:

Unchangeable

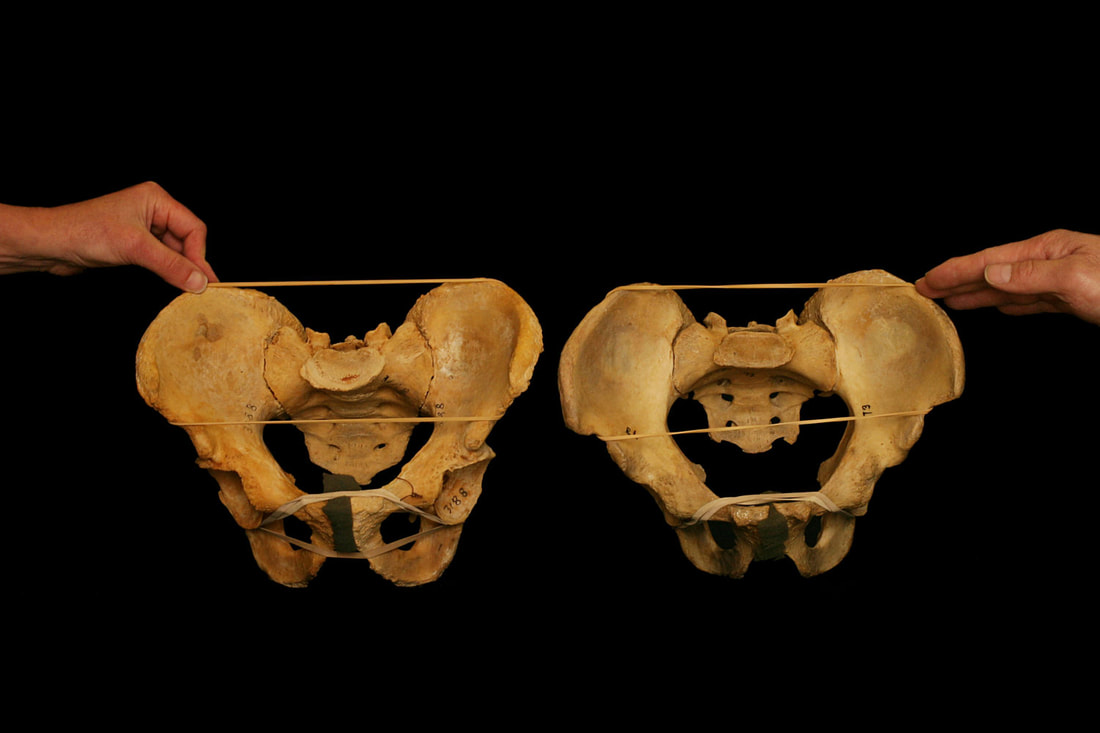

Bone photos by Paul Grilley, open permission via website.

You will NEVER be able to change these things! Thus, comparing yourself to someone who is genetically different is an unfair perspective on yourself. Yes, an X-Ray is really the only way to perfectly identify these differences but, knowing that you are unique and that everyone should have a different process and results should be reassuring to the pace of your process!

So, when it comes to hip mobility, what can we expect to change then? It boils down to three main things:

Mobility training does NOT increase the length of your muscles, NOTHING does! You cannot lengthen muscles as an adult. Once you are done growing, your muscles are essentially at their maximum length. (There is a process of “adding length to muscle” called sarcomeregenesis but by no means will it put your foot behind your head.)

How do we go from “inflexible” to expanding our range of motion? We improve our tolerance to new range of motion (Magnusson, 1996). We are essentially convincing our brain to give us access to new range of motion.

Why don’t we have all of our potential range of motion all the time? The “use it (well) or lose it" principle determines a lot of this. We have access to the ranges that our body is confident enough to allow us to have. That is range of motion that is usually strong, under control, and used often. The “used often” part tends to govern the allowance of range, but as we will learn here, the strength and control portion allow us to keep it long term. That’s where we learn to use it “well.”

Just “using it” is comparable to the cliché of "going through the motions." You are providing your brain and body experience and movement history. The more frequently this occurs the more likely you will have access to this range of motion. However, just because you are using it, perhaps increasing your tolerance to the ranges, does not mean you are using it as you should to improve your strength and control. Those two things are going to be what separates throwing a high heel up on a ledge and getting stuck from being able to drive force into the rock with that heel and leg to move you further up the wall with enough control to grip the next hold efficiently.

So, when it comes to hip mobility, what can we expect to change then? It boils down to three main things:

- your strength

- your movement control, and

- your tolerance to new range of motion.

Mobility training does NOT increase the length of your muscles, NOTHING does! You cannot lengthen muscles as an adult. Once you are done growing, your muscles are essentially at their maximum length. (There is a process of “adding length to muscle” called sarcomeregenesis but by no means will it put your foot behind your head.)

How do we go from “inflexible” to expanding our range of motion? We improve our tolerance to new range of motion (Magnusson, 1996). We are essentially convincing our brain to give us access to new range of motion.

Why don’t we have all of our potential range of motion all the time? The “use it (well) or lose it" principle determines a lot of this. We have access to the ranges that our body is confident enough to allow us to have. That is range of motion that is usually strong, under control, and used often. The “used often” part tends to govern the allowance of range, but as we will learn here, the strength and control portion allow us to keep it long term. That’s where we learn to use it “well.”

Just “using it” is comparable to the cliché of "going through the motions." You are providing your brain and body experience and movement history. The more frequently this occurs the more likely you will have access to this range of motion. However, just because you are using it, perhaps increasing your tolerance to the ranges, does not mean you are using it as you should to improve your strength and control. Those two things are going to be what separates throwing a high heel up on a ledge and getting stuck from being able to drive force into the rock with that heel and leg to move you further up the wall with enough control to grip the next hold efficiently.

To know where you need to go, you need to know where you are: Assessment

Every training program needs to start with an assessment. You need to be aware of your limitations, how to do specifically prescribed exercises, and it serves as comparative information to monitor results and to make any necessary adjustments. For mobility training we assess your passive range of motion (PROM), your active range of motion (AROM), control and strength.

Once you can map out all of these during an initial assessment, your training plan is covering the gap between your goals and the findings of the assessment. As always, getting assessed by a qualified professional (ideally, in person, but this can also be done over video) will give you the best information about where you are starting.

Now we are going to dive into some self-assessment tools and the process of identifying your findings, then understanding what to do with them. The assessment is two parts: the passive test and the active test.

If at any point you feel pain or pinching STOP the movement and make a note. You may have to refer to a health professional such as a therapist or doctor.

- PROM: Range of motion that the body can be PASSIVELY placed into. This is if another person where to take your leg to see how far it bends without your involvement.

- AROM: Range of motion that can ACTIVELY be utilized by the individual. For that same test, now you are moving into that range of motion with your own muscles without any help.

- Control: Can you delicately move through space with coordination?

- Strength: Can you produce enough force or effort to combat the forces being acted on you by the outside world? If we were to arm wrestle, would you be able to hold me in the middle or win (adequate strength for the task) or would you lose or get hurt (inadequate)?

Once you can map out all of these during an initial assessment, your training plan is covering the gap between your goals and the findings of the assessment. As always, getting assessed by a qualified professional (ideally, in person, but this can also be done over video) will give you the best information about where you are starting.

Now we are going to dive into some self-assessment tools and the process of identifying your findings, then understanding what to do with them. The assessment is two parts: the passive test and the active test.

- The passive test utilizes outside help (such as using your arm to move your leg) to observe the motion.

- The active test is using your muscles trying to replicate it.

If at any point you feel pain or pinching STOP the movement and make a note. You may have to refer to a health professional such as a therapist or doctor.

Assessment: Range of Motion

|

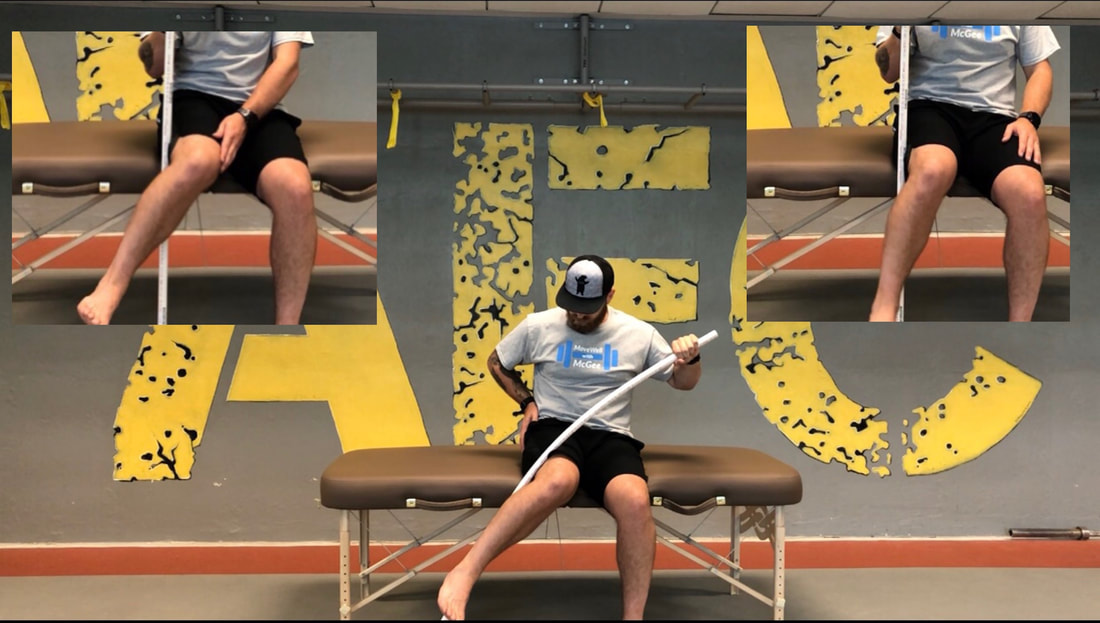

Internal rotation:

Sit with your legs facing forwards and use an object to pry open your hip. If your hip on the same side begins to hike, stop the movement because it is no longer just your hip. Also, make sure your thigh stays in place and does not slide left or right. |

External Rotation:

Sit with your legs relatively forwards and use an object to pry open your hip. If your hip on the same side begins to dip, stop the movement because it is no longer just your hip. Also, make sure your thigh stays in place and does not slide left or right. |

|

Flexion Bent Knee:

Pull your knee to your chest with your hands while keeping the other leg straight. |

Flexion Straight Leg:

Pull your fully extended knee to your chest with your hands while keeping the other leg straight. We are looking at a bent knee as well as a straightened knee because different muscles are put on and off tension. This helps identify issues by process of elimination. This will be the case for many of the tests. |

|

Abduction Bent Knee:

Laying on your side, bend the top knee to about 90 degees and lift it in the air. The hand under your belly and on your hip lets you know when to stop as it will move when you run out of hip. |

Abduction Straight Knee:

Laying on your side, lift a fully straightened leg in the air. The hand under your belly and on your hip lets you know when to stop as it will move when you run out of hip. |

|

Adduction Bent Knee:

Laying on your side, bend the bottom knee to about 90 degrees and lift it in the air. |

Adduction Straight Knee:

Laying on your side, lift a fully straightened bottom leg in the air. |

|

Hip Extension Bent Knee:

Starting on hands and knees, bend the assessment leg and push the heel to the ceiling. You want to stop when you feel the butt block the movement (end of hip) and not your back (spine involvement and top left photo). |

Hip Extension Straight Knee:

Starting on hands and knees, lift the fully straightened leg to the ceiling. You want to stop when you feel the butt block the movement (end of hip) and not your back (spine involvement and top left photo) |

Assessment: Control - Hip CARs

CAR is an acronym for “Controlled Articular Rotation.” With a CAR we are looking for how well you can express all of the movements highlighted above through space while keeping the rest of the body still and under control. The video shows the hip CAR.

Assessment: Strength

Strength testing is relevant to whatever it is you are doing. Different people with different climbing styles will not require the exact same strength. For example, someone’s strength as a V10 boulderer is going to look a lot different than someone climbing 100 foot sport routes.

How much strength do you need and where do you need it? Enough to overcome your task plus a little buffer room to help mitigate injury.

Strength must also be viewed along the speed spectrum. Expressing strength during a dyno or a deadpoint is much different than strength expressed through slow, static climbing. Thus, the training for those things will be different as well.

Note that a human cannot “feel” how strong you are. Again, strong is relevant to the task. If you are getting on and off the couch with ease and able to repeat that over time without injury, you are strong for that task.

To objectively measure strength - which is the amount of force observed by a muscle or movement - you would have to use a measuring device called a dynamometer or force gauge. I personally use the gStrength500 by Exsurgo Technologies. It is a versatile gauge that can be creativity setup to measure any movement. This is useful for testing strength in common, general exercise positions, as well as, in more climbing-specific positions. Coaches who have this tool will be able to give you these special strength assessments, especially coaches that apply the Camp4 Human Performance assessment principles developed by Dr. Tyler Nelson that will translate to rock climbing most specifically.

How much strength do you need and where do you need it? Enough to overcome your task plus a little buffer room to help mitigate injury.

Strength must also be viewed along the speed spectrum. Expressing strength during a dyno or a deadpoint is much different than strength expressed through slow, static climbing. Thus, the training for those things will be different as well.

Note that a human cannot “feel” how strong you are. Again, strong is relevant to the task. If you are getting on and off the couch with ease and able to repeat that over time without injury, you are strong for that task.

To objectively measure strength - which is the amount of force observed by a muscle or movement - you would have to use a measuring device called a dynamometer or force gauge. I personally use the gStrength500 by Exsurgo Technologies. It is a versatile gauge that can be creativity setup to measure any movement. This is useful for testing strength in common, general exercise positions, as well as, in more climbing-specific positions. Coaches who have this tool will be able to give you these special strength assessments, especially coaches that apply the Camp4 Human Performance assessment principles developed by Dr. Tyler Nelson that will translate to rock climbing most specifically.

The Findings

After you complete your self-assessment it is important to reflect on your findings. The findings detail limitations or current baseline numbers and you want to see where you are in relation to what the mobility, strength, control, etc. requirements are for the goals you have, project climbs, or overall life you live. The findings that we will cover will fall into two categories: flexibility and mobility.

Flexibility

If you found yourself unable to get the joint moving with the available passive tests - those which you used your hands or an object to move the joint - this would classify as a flexibility finding. Your joints and the surrounding tissue just don’t want to move into the ranges you desire or need.

Your next steps would then require training based around expanding your tissue's tolerance to a new range of motion. This will still be done primarily with ACTIVE - you participating - interventions. However, lighter effort movements and stretching will also be utilized.

The goal of stretching is not to just mindlessly hang out in random positions. The goal is to learn how to manipulate the body in order to organize and target the desired tissue for which we wish to improve the tolerance. The passive stretch specifically targets the desired tissue/muscles. You then apply the active, strength training efforts, to influence the tolerance and strength of the targeted tissue. This process consistently overtime is what provides long term changes in usable range of motion.

A passive stretch is also how we tone down the nervous system, which ultimately is the main limiter of our range of motion. This is why things like massage “increase flexibility.” The phenomena of touch relaxes the body thoroughly and thus sneaks us some range of motion otherwise inaccessible. However, massage is NOT strength training. It CANNOT improve your muscle's ability to produce force or effort. Thus, although potentially supplemental to the flexibility goals, it alone will not create USABLE range of motion. Your heel will still get “stuck” on that ledge. With enhanced flexibility, we open doors of opportunity to now inject strength and control, transitioning the work to mobility - or that usable range of motion.

Flexibility

If you found yourself unable to get the joint moving with the available passive tests - those which you used your hands or an object to move the joint - this would classify as a flexibility finding. Your joints and the surrounding tissue just don’t want to move into the ranges you desire or need.

Your next steps would then require training based around expanding your tissue's tolerance to a new range of motion. This will still be done primarily with ACTIVE - you participating - interventions. However, lighter effort movements and stretching will also be utilized.

The goal of stretching is not to just mindlessly hang out in random positions. The goal is to learn how to manipulate the body in order to organize and target the desired tissue for which we wish to improve the tolerance. The passive stretch specifically targets the desired tissue/muscles. You then apply the active, strength training efforts, to influence the tolerance and strength of the targeted tissue. This process consistently overtime is what provides long term changes in usable range of motion.

A passive stretch is also how we tone down the nervous system, which ultimately is the main limiter of our range of motion. This is why things like massage “increase flexibility.” The phenomena of touch relaxes the body thoroughly and thus sneaks us some range of motion otherwise inaccessible. However, massage is NOT strength training. It CANNOT improve your muscle's ability to produce force or effort. Thus, although potentially supplemental to the flexibility goals, it alone will not create USABLE range of motion. Your heel will still get “stuck” on that ledge. With enhanced flexibility, we open doors of opportunity to now inject strength and control, transitioning the work to mobility - or that usable range of motion.

Below are two examples of expansive training for hip rotation.

The positions manipulate the ball and socket to fix one and let the other rotate. The nuances of the positions are covered in the two videos below (Front 90 Help and Hip Sleeper).

The goal here is to locate appropriate lines of tension and settle into them with relaxing breathing and some passive stretching. The main course is isometric loading along those specific lines that were found. You would ramp up effort in the direction of the arrows isometrically rotating the hips into the ground. The goal is to be able to hit high intensity, high percentage of maximal voluntary isometric contraction (MVIC) because a minimal effort threshold must be hit in order for change and adaptation to occur. This ability does not typically, nor should, happen in the early weeks of training as this is usually a new concept for the body and new range of motion. But, strength training is the goal so progressive overload is mandatory for change.

Example session: 1-2x per day, 2-3 days per week: Settle into tension/end range and stretch for 30 seconds to 1minute. Isometrically ramp up to your safest, comfortable, max effort for 10 seconds. Re-settle deeper into the position, even if only millimeters. Repeat the process 1-2 more times.

The positions manipulate the ball and socket to fix one and let the other rotate. The nuances of the positions are covered in the two videos below (Front 90 Help and Hip Sleeper).

The goal here is to locate appropriate lines of tension and settle into them with relaxing breathing and some passive stretching. The main course is isometric loading along those specific lines that were found. You would ramp up effort in the direction of the arrows isometrically rotating the hips into the ground. The goal is to be able to hit high intensity, high percentage of maximal voluntary isometric contraction (MVIC) because a minimal effort threshold must be hit in order for change and adaptation to occur. This ability does not typically, nor should, happen in the early weeks of training as this is usually a new concept for the body and new range of motion. But, strength training is the goal so progressive overload is mandatory for change.

Example session: 1-2x per day, 2-3 days per week: Settle into tension/end range and stretch for 30 seconds to 1minute. Isometrically ramp up to your safest, comfortable, max effort for 10 seconds. Re-settle deeper into the position, even if only millimeters. Repeat the process 1-2 more times.

|

|

|

Mobility

This was tested when you tried to match the passive range of motion test with nothing but your active efforts and muscles. Did you get close? Or, were you nowhere near the range you could pull yourself passively into? If you had tons of flexibility, and were nowhere close to matching that motion actively, you have identified a mobility issue. This would look like a passive test like the center image and an active test that looks like the top right image.

You have plenty of potential range of motion, but you do not have complete ownership of it. Stretching and things of that nature would really do you no good here. You don’t have to expand into more range of motion since you have it all already. Your priority now becomes turning that stuff into usable, strong, range of motion.

Below are two examples of mobility training for hip rotation.

Although isometrics in the direction of the floor may still be used in a comprehensive program, now you are adding other interventions with the goal of closing that gap between passive and active ranges.

Actively moving towards that end range, or working very close to it, is now part of the plan.

In the photos are concentric contractions in the relevant directions of rotation. Here the goal is to work in the ranges that are not often used (remember “use it or lose it?”) to create experience, strength, and control. Initially no weight will usually be challenge enough, but again, increasing the challenge is absolutely necessary to continue progress. That means in a few weeks you will be adding weight to the movement. The minimum threshold of effort required to make change increases as you get stronger. That is where a lot of “mobility” work falls short as it continues with efforts that are too easy to continue to make change.

Hip Hip internal rotation RAILs exercises, lifting the ankle off the ground repeatedly.

Example session:

1-2x per day, 2-3 days per week. Find near end range and lift off, hold at the top for a moment, and then slowly descend back to the ground for 2-3 sets 5-8 reps, progressively adding weight over the weeks.

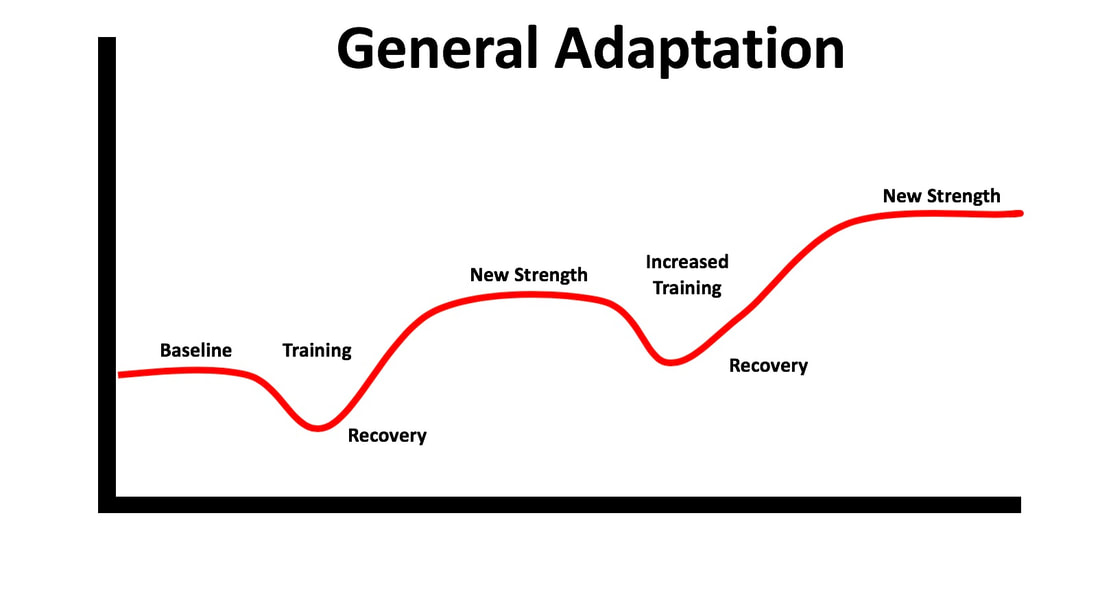

All strength training follows General Adaptation Syndrome. It is how the body responds to stress, or training stimulus, recovers and then adapts stronger. That should clarify why your minimum efforts need to be high and progressively more challenging.

What if your passive and active ranges of motion are pretty close? Well, then refer back to your goals or project and see if your strength and control are where they need to be. Your range of motion may meet the prerequisites for your task but perhaps you need to continue strengthening that range until it is usable enough to be successful and strong enough to be able to mitigate injury. Below you will find some examples of how to continue progressing strength in the “High Foot” movement example.

Isometric Holds & Lift Offs at or near end range

Adding external load and weight to those movements

Isometrics from the high foot end range down into an object from a variety of positions #31 & 32

Hovers

Slow and controlled movement at or near end range over a challenging object to improve control. Also, weight should be added over time.

If you found pain or pinching with any of the assessments or movement that may indicate a joint or tissue that is potentially damaged or needs more professional medical attention from a physical therapist or doctor. Continuously jamming into painful movements is never a good idea for the health of the joint or tissue and is certainly not a great way to make progress with your mobility training. Dr. Tyler Nelson is an exemplary of the type of professional you should seek for situations like these.

If you are interested in how all of this information applies to you specifically, I do virtual 1-on-1 assessments/consultations. It’s a nose to toes assessment of the capabilities of your body and what we would have to do to prepare you for your goals. I also have self-guided training available on my website which walks you through an assessment and then teaches you how to tailor the provided Kinstretch mobility classes to meet your needs.

References

Magnusson S. P., Simonsen E. B., Aagaard P., Soørensen H., Kjær M. (1996) A mechanism for altered flexibility in human skeletal muscle. Journal of Physiology 497(1), 291-298

A Special For Common Climbers through September!

- 25% off the Move Better Program for the month of September. Use the code (normally $100, now $75): CCSeptember

- 25% off 1-on-1 personal training assessment: Contact Collin McGee via email at [email protected] and mention this article and the code "CCSeptember" (normally $100, now $75)