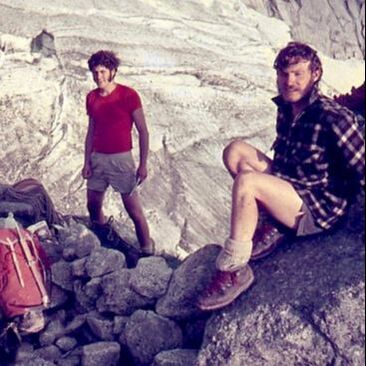

In 1971, four young Aussie friends go to Chamonix, France to climb the North Face of the Petit Dru (among other things). The Petit Dru is an 800-meter (2625-feet) mixed rock and ice climb. Keith Bell, John Fantini, Chris Baxter, and Howard Bevan pair up (Keith and John, Chris and Howard) and unknowingly enter into a no-holds-barred race to the top in this challenging terrain with 10+ other parties.

The friends end up losing track of each other while on the mountain and have two completely different experiences - each described here in Common Climber in a unique "tale of two climbs" stories. On this page, Keith Bell shares his experience in "Horses for Courses: The Dru Derby 1971" while Howard Bevan shares "My Dru Derby"

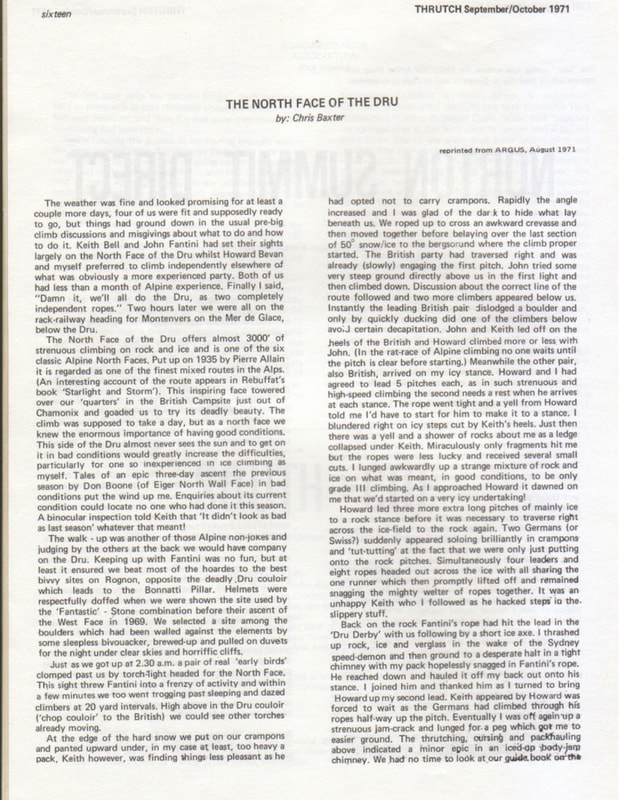

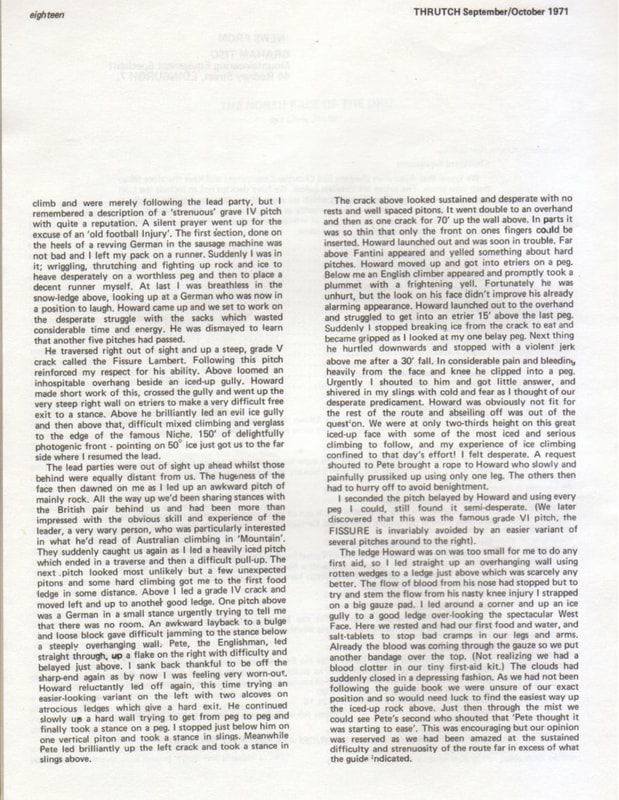

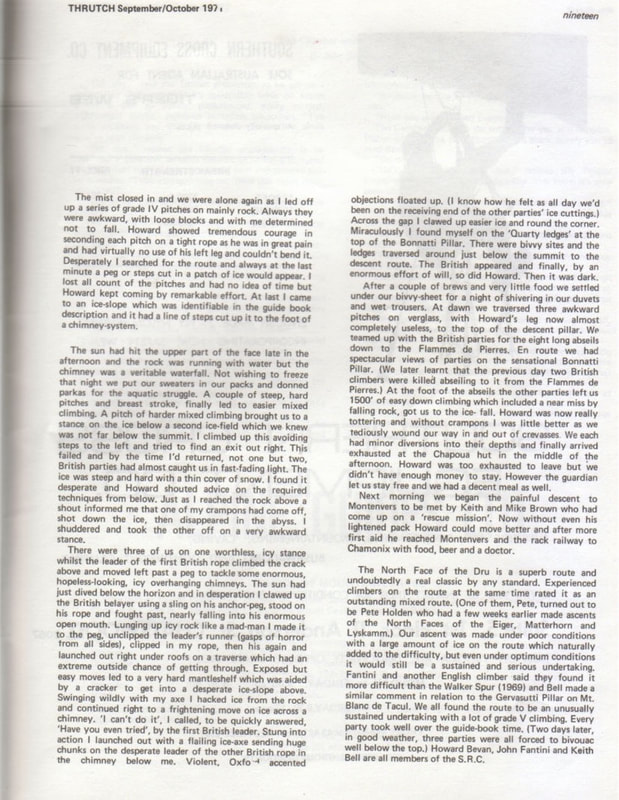

In a cool trifecta, we also have a copy of the original published account by Chris Baxter. In 1971 the story was published in Argus, the newsletter of the Victoria Climbing Climb of Mebourne, Australia, and Thrutch, an Austal-Asian climbing magazine. Read all three and experience the unique perspectives of each climber! (EDITOR'S NOTE: We have included images of the original article and have adjusted the paragraph breaks here to allow more white space for easier reading in this online format.)

The friends end up losing track of each other while on the mountain and have two completely different experiences - each described here in Common Climber in a unique "tale of two climbs" stories. On this page, Keith Bell shares his experience in "Horses for Courses: The Dru Derby 1971" while Howard Bevan shares "My Dru Derby"

In a cool trifecta, we also have a copy of the original published account by Chris Baxter. In 1971 the story was published in Argus, the newsletter of the Victoria Climbing Climb of Mebourne, Australia, and Thrutch, an Austal-Asian climbing magazine. Read all three and experience the unique perspectives of each climber! (EDITOR'S NOTE: We have included images of the original article and have adjusted the paragraph breaks here to allow more white space for easier reading in this online format.)

This side of the Dru almost never sees the sun and to get on it in bad conditions would greatly increase the difficulties, particularly for one so inexperienced in ice climbing as myself. Tales of an epic three-day ascent the previous season by Don Boone (of Eiger North Wall Face) in bad conditions put the wind up me. Enquiries about its current condition could locate no one who had done it this season. A binocular inspection told Keith that 'It didn't look as bad as last season' whatever that meant!

The walk-up was another of those Alpine non-jokes and judging by the others at the back we would have company on the Dru. Keeping up with Fantini was no fun, but at least it ensured we beat most of the hoardes to the best bivvy sites on Rognon, opposite the deadly Dru couloir which leads to the Bonnatti Pillar. Helmets were respectfully doffed when we were shown the site used by the 'Fantastic' Stone combination before their ascent of the West Face in 1969. We selected a site among the boulders which had been walled against the elements by some sleepless bivouacker, brewed-up and pulled on duvets for the night under clear skies and horrific cliffs.

Just as we got up at 2.30 a.m. a pair of real 'early birds' clomped past us by torch-light headed for the North Face. This sight threw Fantini into a frenzy of activity and within a few minutes we too went trogging past sleeping and dazed climbers at 20 yard intervals. High above in the Dru couloir ('chop couloir' to the British) we could see other torches already moving.

At the edge of the hard snow we put on our crampons and panted upward under, in my case at least, too heavy a pack, Keith however, was finding things less pleasant as he had opted not to carry crampons. Rapidly the angle increased and I was glad of the dark to hide what lay beneath us.

We roped up to cross an awkward crevasse and then moved together before belaying over the last section of 50\'b0 snow/ice to the bergsorund where the climb proper started. The British party had traversed right and was already (slowly) engaging the first pitch. John tried some very steep ground directly above us in the first light and then climbed down. Discussion about the correct line of the route followed and two more climbers appeared below us. Instantly the leading British pair dislodged a boulder and only by quickly ducking did one of the climbers below avoid certain decapitation. John and Keith led off on the heels of the British and Howard climbed more or less with John. (In the rat-race of Alpine climbing no one waits until the pitch is clear before starting.)

Meanwhile the other pair, also British, arrived on my icy stance. Howard and I had agreed to lead 5 pitches each, as in such strenuous and high-speed climbing the second needs a rest when he arrives at each stance. The rope went tight and a yell from Howard told me I'd have to start for him to make it to a stance. I blundered right on icy steps cut by Keith's heels. Just then there was a yell and a shower of rocks about me as a ledge collapsed under Keith. Miraculously only fragments hit me but the ropes were less lucky and received several small cuts.

I lunged awkwardly up a strange mixture of rock and ice on what was meant, in good conditions, to be only grade III climbing. As I approached Howard it dawned on me that we'd started on a very icy undertaking! Howard led three more extra long pitches of mainly ice to a rock stance before it was necessary to traverse right across the ice-field to the rock again. Two Germans (or Swiss?) suddenly appeared soloing brilliantly in crampons and 'tut-tutting' at the fact that we were only just putting onto the rock pitches. Simultaneously four leaders and eight ropes headed out across the ice with all sharing the one runner which then promptly lifted off and remained snagging the mighty welter of ropes together. It was an unhappy Keith who I followed as he hacked steps in the. slippery stuff.

The walk-up was another of those Alpine non-jokes and judging by the others at the back we would have company on the Dru. Keeping up with Fantini was no fun, but at least it ensured we beat most of the hoardes to the best bivvy sites on Rognon, opposite the deadly Dru couloir which leads to the Bonnatti Pillar. Helmets were respectfully doffed when we were shown the site used by the 'Fantastic' Stone combination before their ascent of the West Face in 1969. We selected a site among the boulders which had been walled against the elements by some sleepless bivouacker, brewed-up and pulled on duvets for the night under clear skies and horrific cliffs.

Just as we got up at 2.30 a.m. a pair of real 'early birds' clomped past us by torch-light headed for the North Face. This sight threw Fantini into a frenzy of activity and within a few minutes we too went trogging past sleeping and dazed climbers at 20 yard intervals. High above in the Dru couloir ('chop couloir' to the British) we could see other torches already moving.

At the edge of the hard snow we put on our crampons and panted upward under, in my case at least, too heavy a pack, Keith however, was finding things less pleasant as he had opted not to carry crampons. Rapidly the angle increased and I was glad of the dark to hide what lay beneath us.

We roped up to cross an awkward crevasse and then moved together before belaying over the last section of 50\'b0 snow/ice to the bergsorund where the climb proper started. The British party had traversed right and was already (slowly) engaging the first pitch. John tried some very steep ground directly above us in the first light and then climbed down. Discussion about the correct line of the route followed and two more climbers appeared below us. Instantly the leading British pair dislodged a boulder and only by quickly ducking did one of the climbers below avoid certain decapitation. John and Keith led off on the heels of the British and Howard climbed more or less with John. (In the rat-race of Alpine climbing no one waits until the pitch is clear before starting.)

Meanwhile the other pair, also British, arrived on my icy stance. Howard and I had agreed to lead 5 pitches each, as in such strenuous and high-speed climbing the second needs a rest when he arrives at each stance. The rope went tight and a yell from Howard told me I'd have to start for him to make it to a stance. I blundered right on icy steps cut by Keith's heels. Just then there was a yell and a shower of rocks about me as a ledge collapsed under Keith. Miraculously only fragments hit me but the ropes were less lucky and received several small cuts.

I lunged awkwardly up a strange mixture of rock and ice on what was meant, in good conditions, to be only grade III climbing. As I approached Howard it dawned on me that we'd started on a very icy undertaking! Howard led three more extra long pitches of mainly ice to a rock stance before it was necessary to traverse right across the ice-field to the rock again. Two Germans (or Swiss?) suddenly appeared soloing brilliantly in crampons and 'tut-tutting' at the fact that we were only just putting onto the rock pitches. Simultaneously four leaders and eight ropes headed out across the ice with all sharing the one runner which then promptly lifted off and remained snagging the mighty welter of ropes together. It was an unhappy Keith who I followed as he hacked steps in the. slippery stuff.

(Click on the image above to enlarge and view the original article.)

Back on the rock Fantini's rope had hit the lead in the 'Dru Derby' with us following by a short ice axe. I thrashed up rock, ice and verglass in the wake of the Sydney speed-demon and then ground to a desperate halt in a tight chimney with my pack hopelessly snagged in Fantini's rope. He reached down and hauled it off my back out onto his stance. I joined him and thanked him as I turned to bring Howard up my second lead.

Keith appeared by Howard was forced to wait as the Germans had climbed through his ropes half-way up the pitch. Eventually I was off again up a strenuous jam-crack and lunged for a peg which got me to easier ground. The thrutching, cursing and packhauling above indicated a minor epic in an iced-up body-jam chimney. We had no time to look at our guide book on the climb and were merely following the lead party, but I remembered a description of a 'strenuous' grave IV pitch with quite a reputation. A silent prayer went up for the excuse of an 'old football Injury'.

The first section, done on the heels of a revving German in the sausage machine was not bad and I left my pack on a runner. Suddenly I was in it; wriggling, thrutching and fighting up rock and ice to heave desperately on a worthless peg and then to place a decent runner myself. At last I was breathless in the snow-ledge above, looking up at a German who was now in a position to laugh. Howard came up and we set to work on the desperate struggle with the sacks which wasted considerable time and energy. He was dismayed to learn that another five pitches had passed.

He traversed right out of sight and up a steep, grade V crack called the Fissure Lambert. Following this pitch reinforced my respect for his ability. Above loomed an inhospitable overhang beside an iced-up gully. Howard made short work of this, crossed the gully and went up the very steep right wall on etriers to make a very difficult free exit to a stance. Above he brilliantly led an evil ice gully and then above that, difficult mixed climbing and verglass to the edge of the famous Niche. 150' of delightfully photogenic front pointing on 50\'b0 ice just got us to the far side where I resumed the lead.

The lead parties were out of sight up ahead whilst those behind were equally distant from us. The hugeness of the face then dawned on me as I led up an awkward pitch of mainly rock. All the way up we'd been sharing stances with the British pair behind us and had been more than impressed with the obvious skill and experience of the leader, a very wary person, who was particularly interested in what he'd read of Australian climbing in 'Mountain'.

They suddenly caught us again as I led a heavily iced pitch which ended in a traverse and then a difficult pull-up. The next pitch looked most unlikely but a few unexpected pitons and some hard climbing got me to the first food ledge in some distance. Above I led a grade IV crack and moved left and up to another good ledge. One pitch above was a German in a small stance urgently trying to tell me that there was no room. An awkward layback to a bulge and loose block gave difficult jamming to the stance below a steeply overhanging wall. Pete, the Englishman, led straight through, up a flake on the right with difficulty and belayed just above.

I sank back thankful to be off the sharp-end again as by now I was feeling very worn-out. Howard reluctantly led off again, this time trying an easier-looking variant on the left with two alcoves on atrocious ledges which give a hard exit. He continued slowly up a hard wall trying to get from peg to peg and finally took a stance on a peg. I stopped just below him on one vertical piton and took a stance in slings. Meanwhile Pete led brilliantly up the left crack and took a stance in slings above.

The crack above looked sustained and desperate with no rests and well spaced pitons. It went double to an overhand and then as one crack for 70' up the wall above. In parts it was so thin that only the front on ones fingers could be inserted. Howard launched out and was soon in trouble. Far above Fantini appeared and yelled something about hard pitches. Howard moved up and got into etriers on a peg. Below me an English climber appeared and promptly took a plummet with a frightening yell. Fortunately he was unhurt, but the look on his face didn't improve his already alarming appearance.

Howard launched out to the overhand and struggled to get into an etrier 15' above the last peg. Suddenly I stopped breaking ice from the crack to eat and became gripped as I looked at my one belay peg. Next thing he hurtled downwards and stopped with a violent jerk above me after a 30' fall. In considerable pain and bleeding heavily from the face and knee he clipped into a peg. Urgently I shouted to him and got little answer, and shivered in my slings with cold and fear as I thought of our desperate predicament. Howard was obviously not fit for the rest of the route and abseiling off was out of the question. We were at only two-thirds height on this great iced-up face with some of the most iced and serious climbing to follow, and my experience of ice climbing confined to that day's effort! I felt desperate. A request shouted to Pete brought a rope to Howard who slowly and painfully prussiked up using only one leg. The others then had to hurry off to avoid benightment.

I seconded the pitch belayed by Howard and using every peg I could, still found it semi-desperate. (We later discovered that this was the famous grade VI pitch, the FISSURE is invariably avoided by an easier variant of several pitches around to the right).

The ledge Howard was on was too small for me to do any first aid, so I led straight up an overhanging wall using rotten wedges to a ledge just above which was scarcely any better. The flow of blood from his nose had stopped but to try and stem the flow from his nasty knee injury I strapped on a big gauze pad. I led around a corner and up an ice gully to a good ledge over-looking the spectacular West Face. Here we rested and had our first food and water, and salt-tablets to stop bad cramps in our legs and arms. Already the blood was coming through the gauze so we put another bandage over the top. (Not realizing we had a blood clotter in our tiny first-aid kit.)

The clouds had suddenly closed in a depressing fashion. As we had not been following the guide book we were unsure of our exact position and so would need luck to find the easiest way up the iced-up rock above. Just then through the mist we could see Pete's second who shouted that 'Pete thought it was starting to ease'. This was encouraging but our opinion was reserved as we had been amazed at the sustained difficulty and strenuosity of the route far in excess of what the guide indicated.

The mist closed in and we were alone again as I led off up a series of grade IV pitches on mainly rock. Always they were awkward, with loose blocks and with me determined not to fall. Howard showed tremendous courage in seconding each pitch on a tight rope as he was in great pain and had virtually no use of his left leg and couldn't bend it. Desperately I searched for the route and always at the last minute a peg or steps cut in a patch of ice would appear. I lost all count of the pitches and had no idea of time but Howard kept coming by remarkable effort. At last I came to an ice-slope which was identifiable in the guide book description and it had a line of steps cut up it to the foot of a chimney-system.

The sun had hit the upper part of the face late in the afternoon and the rock was running with water but the chimney was a veritable waterfall. Not wishing to freeze that night we put our sweaters in our packs and donned parkas for the aquatic struggle. A couple of steep, hard pitches and breast stroke, finally led to easier mixed climbing. A pitch of harder mixed climbing brought us to a stance on the ice below a second ice-field which we knew was not far below the summit. I climbed up this avoiding steps to the left and tried to find an exit out right. This failed and by the time I'd returned, not one but two, British parties had almost caught us in fast-fading light. The ice was steep and hard with a thin cover of snow. I found it desperate and Howard shouted advice on the required techniques from below. Just as I reached the rock above a shout informed me that one of my crampons had come off, shot down the ice, then disappeared in the abyss. I shuddered and took the other off on a very awkward stance.

There were three of us on one worthless, icy stance whilst the leader of the first British rope climbed the crack above and moved left past a peg to tackle some enormous, hopeless-looking, icy overhanging chimneys. The sun had just dived below the horizon and in desperation I clawed up the British belayer using a sling on his anchor-peg, stood on his rope and fought past, nearly falling into his enormous open mouth. Lunging up icy rock like a mad-man I made it to the peg, unclipped the leader's runner (gasps of horror from all sides), clipped in my rope, then his again and launched out right under roofs on a traverse which had an extreme outside chance of getting through. Exposed but easy moves led to a very hard mantleshelf which was aided by a cracker to get into a desperate ice-slope above.

Swinging wildly with my axe I hacked ice from the rock and continued right to a frightening move on ice across a chimney. 'I can't do it', I called, to be quickly answered, 'Have you even tried', by the first British leader. Stung into action I launched out with a flailing ice-axe sending huge chunks on the desperate leader of the other British rope in the chimney below me. Violent, Oxfo accented objections floated up. (I know how he felt as all day we'd been on the receiving end of the other parties' ice cuttings.) Across the gap I clawed up easier ice and round the corner. Miraculously I found myself on the 'Quarty ledges' at the top of the Bonnatti Pillar. There were bivvy sites and the ledges traversed around just below the summit to the descent route. The British appeared and finally, by an enormous effort of will, so did Howard. Then it was dark.

After a couple of brews and very little food we settled under our bivvy-sheet for a night of shivering in our duvets and wet trousers. At dawn we traversed three awkward pitches on verglass, with Howard's leg now almost completely useless, to the top of the descent pillar. We teamed up with the British parties for the eight long abseils down to the Flammes de Pierres. En route we had spectacular views of parties on the sensational Bonnatti Pillar. (We later learnt that the previous day two British climbers were killed abseiling to it from the Flammes de Pierres.) At the foot of the abseils the other parties left us 1500' of easy down climbing which included a near miss by falling rock, got us to the ice- fall. Howard was now really tottering and without crampons I was little better as we tediously wound our way in and out of crevasses. We each had minor diversions into their depths and finally arrived exhausted at the Chapoua hut in the middle of the afternoon. Howard was too exhausted to leave but we didn't have enough money to stay. However the guardian let us stay free and we had a decent meal as well.

Next morning we began the painful descent to Montenvers to be met by Keith and Mike Brown who had come up on a 'rescue mission'. Now without even his lightened pack Howard could move better and after more first aid he reached Montenvers and the rack railway to Chamonix with food, beer and a doctor.

The North Face of the Dru is a superb route and undoubtedly a real classic by any standard. Experienced climbers on the route at the same time rated it as an outstanding mixed route. (One of them, Pete, turned out to be Pete Holden who had a few weeks earlier made ascents of the North Faces of the Eiger, Matterhorn and Lyskamm.) Our ascent was made under poor conditions with a large amount of ice on the route which naturally added to the difficulty, but even under optimum conditions it would still be a sustained and serious undertaking. Fantini and another English climber said they found it more difficult than the Walker Spur (1969) and Bell made a similar comment in relation to the Gervasutti Pillar on Mt. Blanc de Tacul. We all found the route to be an unusually sustained undertaking with a lot of grade V climbing. Every party took well over the guide-book time. (Two days later, in good weather, three parties were all forced to bivouac well below the top.) Howard Bevan, John Fantini and Keith Bell are all members of the S.R.C.

Keith appeared by Howard was forced to wait as the Germans had climbed through his ropes half-way up the pitch. Eventually I was off again up a strenuous jam-crack and lunged for a peg which got me to easier ground. The thrutching, cursing and packhauling above indicated a minor epic in an iced-up body-jam chimney. We had no time to look at our guide book on the climb and were merely following the lead party, but I remembered a description of a 'strenuous' grave IV pitch with quite a reputation. A silent prayer went up for the excuse of an 'old football Injury'.

The first section, done on the heels of a revving German in the sausage machine was not bad and I left my pack on a runner. Suddenly I was in it; wriggling, thrutching and fighting up rock and ice to heave desperately on a worthless peg and then to place a decent runner myself. At last I was breathless in the snow-ledge above, looking up at a German who was now in a position to laugh. Howard came up and we set to work on the desperate struggle with the sacks which wasted considerable time and energy. He was dismayed to learn that another five pitches had passed.

He traversed right out of sight and up a steep, grade V crack called the Fissure Lambert. Following this pitch reinforced my respect for his ability. Above loomed an inhospitable overhang beside an iced-up gully. Howard made short work of this, crossed the gully and went up the very steep right wall on etriers to make a very difficult free exit to a stance. Above he brilliantly led an evil ice gully and then above that, difficult mixed climbing and verglass to the edge of the famous Niche. 150' of delightfully photogenic front pointing on 50\'b0 ice just got us to the far side where I resumed the lead.

The lead parties were out of sight up ahead whilst those behind were equally distant from us. The hugeness of the face then dawned on me as I led up an awkward pitch of mainly rock. All the way up we'd been sharing stances with the British pair behind us and had been more than impressed with the obvious skill and experience of the leader, a very wary person, who was particularly interested in what he'd read of Australian climbing in 'Mountain'.

They suddenly caught us again as I led a heavily iced pitch which ended in a traverse and then a difficult pull-up. The next pitch looked most unlikely but a few unexpected pitons and some hard climbing got me to the first food ledge in some distance. Above I led a grade IV crack and moved left and up to another good ledge. One pitch above was a German in a small stance urgently trying to tell me that there was no room. An awkward layback to a bulge and loose block gave difficult jamming to the stance below a steeply overhanging wall. Pete, the Englishman, led straight through, up a flake on the right with difficulty and belayed just above.

I sank back thankful to be off the sharp-end again as by now I was feeling very worn-out. Howard reluctantly led off again, this time trying an easier-looking variant on the left with two alcoves on atrocious ledges which give a hard exit. He continued slowly up a hard wall trying to get from peg to peg and finally took a stance on a peg. I stopped just below him on one vertical piton and took a stance in slings. Meanwhile Pete led brilliantly up the left crack and took a stance in slings above.

The crack above looked sustained and desperate with no rests and well spaced pitons. It went double to an overhand and then as one crack for 70' up the wall above. In parts it was so thin that only the front on ones fingers could be inserted. Howard launched out and was soon in trouble. Far above Fantini appeared and yelled something about hard pitches. Howard moved up and got into etriers on a peg. Below me an English climber appeared and promptly took a plummet with a frightening yell. Fortunately he was unhurt, but the look on his face didn't improve his already alarming appearance.

Howard launched out to the overhand and struggled to get into an etrier 15' above the last peg. Suddenly I stopped breaking ice from the crack to eat and became gripped as I looked at my one belay peg. Next thing he hurtled downwards and stopped with a violent jerk above me after a 30' fall. In considerable pain and bleeding heavily from the face and knee he clipped into a peg. Urgently I shouted to him and got little answer, and shivered in my slings with cold and fear as I thought of our desperate predicament. Howard was obviously not fit for the rest of the route and abseiling off was out of the question. We were at only two-thirds height on this great iced-up face with some of the most iced and serious climbing to follow, and my experience of ice climbing confined to that day's effort! I felt desperate. A request shouted to Pete brought a rope to Howard who slowly and painfully prussiked up using only one leg. The others then had to hurry off to avoid benightment.

I seconded the pitch belayed by Howard and using every peg I could, still found it semi-desperate. (We later discovered that this was the famous grade VI pitch, the FISSURE is invariably avoided by an easier variant of several pitches around to the right).

The ledge Howard was on was too small for me to do any first aid, so I led straight up an overhanging wall using rotten wedges to a ledge just above which was scarcely any better. The flow of blood from his nose had stopped but to try and stem the flow from his nasty knee injury I strapped on a big gauze pad. I led around a corner and up an ice gully to a good ledge over-looking the spectacular West Face. Here we rested and had our first food and water, and salt-tablets to stop bad cramps in our legs and arms. Already the blood was coming through the gauze so we put another bandage over the top. (Not realizing we had a blood clotter in our tiny first-aid kit.)

The clouds had suddenly closed in a depressing fashion. As we had not been following the guide book we were unsure of our exact position and so would need luck to find the easiest way up the iced-up rock above. Just then through the mist we could see Pete's second who shouted that 'Pete thought it was starting to ease'. This was encouraging but our opinion was reserved as we had been amazed at the sustained difficulty and strenuosity of the route far in excess of what the guide indicated.

The mist closed in and we were alone again as I led off up a series of grade IV pitches on mainly rock. Always they were awkward, with loose blocks and with me determined not to fall. Howard showed tremendous courage in seconding each pitch on a tight rope as he was in great pain and had virtually no use of his left leg and couldn't bend it. Desperately I searched for the route and always at the last minute a peg or steps cut in a patch of ice would appear. I lost all count of the pitches and had no idea of time but Howard kept coming by remarkable effort. At last I came to an ice-slope which was identifiable in the guide book description and it had a line of steps cut up it to the foot of a chimney-system.

The sun had hit the upper part of the face late in the afternoon and the rock was running with water but the chimney was a veritable waterfall. Not wishing to freeze that night we put our sweaters in our packs and donned parkas for the aquatic struggle. A couple of steep, hard pitches and breast stroke, finally led to easier mixed climbing. A pitch of harder mixed climbing brought us to a stance on the ice below a second ice-field which we knew was not far below the summit. I climbed up this avoiding steps to the left and tried to find an exit out right. This failed and by the time I'd returned, not one but two, British parties had almost caught us in fast-fading light. The ice was steep and hard with a thin cover of snow. I found it desperate and Howard shouted advice on the required techniques from below. Just as I reached the rock above a shout informed me that one of my crampons had come off, shot down the ice, then disappeared in the abyss. I shuddered and took the other off on a very awkward stance.

There were three of us on one worthless, icy stance whilst the leader of the first British rope climbed the crack above and moved left past a peg to tackle some enormous, hopeless-looking, icy overhanging chimneys. The sun had just dived below the horizon and in desperation I clawed up the British belayer using a sling on his anchor-peg, stood on his rope and fought past, nearly falling into his enormous open mouth. Lunging up icy rock like a mad-man I made it to the peg, unclipped the leader's runner (gasps of horror from all sides), clipped in my rope, then his again and launched out right under roofs on a traverse which had an extreme outside chance of getting through. Exposed but easy moves led to a very hard mantleshelf which was aided by a cracker to get into a desperate ice-slope above.

Swinging wildly with my axe I hacked ice from the rock and continued right to a frightening move on ice across a chimney. 'I can't do it', I called, to be quickly answered, 'Have you even tried', by the first British leader. Stung into action I launched out with a flailing ice-axe sending huge chunks on the desperate leader of the other British rope in the chimney below me. Violent, Oxfo accented objections floated up. (I know how he felt as all day we'd been on the receiving end of the other parties' ice cuttings.) Across the gap I clawed up easier ice and round the corner. Miraculously I found myself on the 'Quarty ledges' at the top of the Bonnatti Pillar. There were bivvy sites and the ledges traversed around just below the summit to the descent route. The British appeared and finally, by an enormous effort of will, so did Howard. Then it was dark.

After a couple of brews and very little food we settled under our bivvy-sheet for a night of shivering in our duvets and wet trousers. At dawn we traversed three awkward pitches on verglass, with Howard's leg now almost completely useless, to the top of the descent pillar. We teamed up with the British parties for the eight long abseils down to the Flammes de Pierres. En route we had spectacular views of parties on the sensational Bonnatti Pillar. (We later learnt that the previous day two British climbers were killed abseiling to it from the Flammes de Pierres.) At the foot of the abseils the other parties left us 1500' of easy down climbing which included a near miss by falling rock, got us to the ice- fall. Howard was now really tottering and without crampons I was little better as we tediously wound our way in and out of crevasses. We each had minor diversions into their depths and finally arrived exhausted at the Chapoua hut in the middle of the afternoon. Howard was too exhausted to leave but we didn't have enough money to stay. However the guardian let us stay free and we had a decent meal as well.

Next morning we began the painful descent to Montenvers to be met by Keith and Mike Brown who had come up on a 'rescue mission'. Now without even his lightened pack Howard could move better and after more first aid he reached Montenvers and the rack railway to Chamonix with food, beer and a doctor.

The North Face of the Dru is a superb route and undoubtedly a real classic by any standard. Experienced climbers on the route at the same time rated it as an outstanding mixed route. (One of them, Pete, turned out to be Pete Holden who had a few weeks earlier made ascents of the North Faces of the Eiger, Matterhorn and Lyskamm.) Our ascent was made under poor conditions with a large amount of ice on the route which naturally added to the difficulty, but even under optimum conditions it would still be a sustained and serious undertaking. Fantini and another English climber said they found it more difficult than the Walker Spur (1969) and Bell made a similar comment in relation to the Gervasutti Pillar on Mt. Blanc de Tacul. We all found the route to be an unusually sustained undertaking with a lot of grade V climbing. Every party took well over the guide-book time. (Two days later, in good weather, three parties were all forced to bivouac well below the top.) Howard Bevan, John Fantini and Keith Bell are all members of the S.R.C.