I slumped at my desk on Monday morning in complete dysfunction before the first cup of coffee. The hearty aroma of fresh brew forced my eyes to open as I raised the mug to drink. One sip of the magic elixir jump started the chemical motor in my brain. I noticed a photograph laying on my desk which had eluded my uncaffinated vision a moment before. The photograph contained the image of a distant mountain with impressive rock walls.

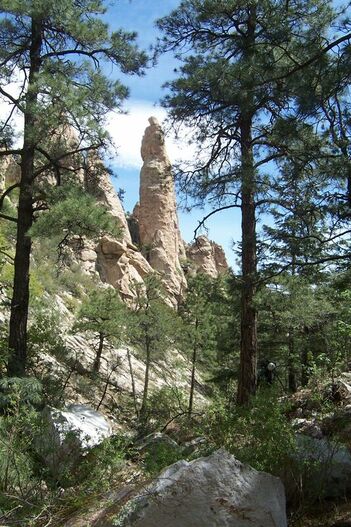

Where is this place? Who left this photograph? I studied it closer. The photo showed a landscape of desert scrub leading to forested mountains from which huge spires and walls of pinkish, possibly granitic rock, rose. Instinctively, I scanned the rock walls for features and climbing lines. "Wow" was all I could muster in my brain and it was much too early in the morning to play Sherlock Holmes; I was feeling more like Watson.

Where is this place? Who left this photograph? I studied it closer. The photo showed a landscape of desert scrub leading to forested mountains from which huge spires and walls of pinkish, possibly granitic rock, rose. Instinctively, I scanned the rock walls for features and climbing lines. "Wow" was all I could muster in my brain and it was much too early in the morning to play Sherlock Holmes; I was feeling more like Watson.

Will Murley appeared in the doorway of my office with his spittin' cup in one hand and a stained coffee mug in the other. Will is a geologist and a west Texas cowboy from head to toe. His nickname, "Drill" Murley, reflects his enthusiasm for the oilfield and his rugged but friendly nature. He walked over to the desk, sat down in the chair and began to describe the ranch in New Mexico where the photo was taken, Las Palas. The photo was large format and contained a distant view of the ranch and mountains beyond. It was taken by Will’s Sister-in-law Annie from an adjacent hill on a neighboring ranch. The photo was very clear, revealing intriguing features and details in the rock even from afar. The ranch house was nestled in a grove of alligator juniper and the foot of a large canyon draining out of the mountains toward the plain below. It was owned by Edith Standhart, Will’s Mother-in-law, who lived in this remote location with her daughter Annie. Will knew I was a climber and thought he'd lure me in with that image. It worked.

Will talked about the wildness of the surrounding land, the frontier history of the property and how it was full of old ruins and artifacts from western settlers; legends from days gone by. Then he dropped some hints that I'm welcome to join him up there sometime. I woke up a little more. Suddenly, those craggy peaks moved from a distant photo into possibility. I started to ask what he knew about the peaks for climbing. Not much, it was clear. They are so remote and difficult to access he doubted if they've ever been climbed - at least the way I like to climb rocks. Then he looked straight at me, with a seriousness and change of tone that took me by surprise, and said, "There are a lot of bears up there." The look on his face and seriousness of his statement made me lose my previous train of thought. I wasn't sure if he was now trying to discourage me or to test my resolve. I shared some stories of my prior experiences with black bears in the wilderness and described the precautions one normally takes to avoid contact. But, something in his voice and words emphasized that this place belonged to the bears.

Several months later in the Spring of 1991, Will and his wife, Barbara, were planning a trip to Las Palas and asked if I wanted to go along. Suddenly, those mountains moved from possibility to reality. I had to see what they held. This would be adventure climbing on steroids in a new and untamed area, and I needed partners that wanted to play. I organized a quick weekend trip and invited three friends: James Crump, Larry Gunn, and David Cain. James and I had been climbing together for over a decade and had just spent two weeks the previous summer climbing in the Bugaboos in Canada. Larry and Dave are local Texas climbers and had helped me put up numerous routes in the Pecos River Gorge.

After picking up James, we stopped to get groceries at the overpriced natural food store and walked away blowing the dust from our empty wallets. In true Texas yahoo style, James managed to spend all his money before we even left town. James is truly a unique phenomenon and most certainly a lifetime psychology study. He is a self-described "more-ist," which very simply stated is one who believes in the axiom that "more is always better." Several corollaries have evolved from this philosophy, mostly dealing with the mechanics of how to get more. In his quest for more, James had become the master of zero budget financing (a term which he also coined) which allows him to maximize the amount of stuff he can get with no money. A good rock climbing analogy for this philosophy would be running it out on thin slab, for which James is also a master.

That evening we pulled our circus act together, juggled the stuff into Larry's van and drove all night to arrive at La Palas, arriving by dawn. Dave pulled the graveyard shift, driving through the toughest early morning hours, arriving with the sun. The air was cool and crisp. The windows were rolled down and the fresh aromatic smell of pinon and juniper filled the van.

Suddenly, I fired off a series of commands: "OK, wake up you guys!" "Who's got the map?" "Turn left on the gravel road!" "Ok, which gravel road?" We tried to orient ourselves in the half-light and road-washed brains. "Shit!" We all belched out in synchrony as we swerved to miss a large deer stepping out in front of the moving van. Everyone was definitely awake now and despite Dave's skepticism and my cryptic scribbled directions, the road we were on led us straight to the place.

We drove up the gravel road and parked the van outside the gate surrounding a historic stucco house with rusted metal roof and painted wooden window sashes. The place was well-maintained and distinctly New Mexican territorial style. We had arrived at Las Palas, which was once a community of ranchers and loggers with more than a hundred people. The central portion of the home consisted of the original stucco walls and stone floors from an old cantina, which had been restored to create the living and dining areas. Additions to either side of the original cantina formed the bedrooms, kitchen, and bath.

Many years ago Las Palas housed woodcutters that derived their existence from harvesting the mountain timber. Long since gone, many ruins and artifacts of the old community are located within the ranch, including a small adobe building and remnant objects like bed frames and metal stove parts. It was also rumored to have been an old haunt of Billy the Kid, a famous western outlaw.

I slowly pulled on my shoes and quietly climbed out of the van. The still morning air begged for quiet - no chickens, no dogs, no cows - nothing was present to announce our arrival. It was like a great outdoor cathedral and I felt respectful of the beauty.

Will talked about the wildness of the surrounding land, the frontier history of the property and how it was full of old ruins and artifacts from western settlers; legends from days gone by. Then he dropped some hints that I'm welcome to join him up there sometime. I woke up a little more. Suddenly, those craggy peaks moved from a distant photo into possibility. I started to ask what he knew about the peaks for climbing. Not much, it was clear. They are so remote and difficult to access he doubted if they've ever been climbed - at least the way I like to climb rocks. Then he looked straight at me, with a seriousness and change of tone that took me by surprise, and said, "There are a lot of bears up there." The look on his face and seriousness of his statement made me lose my previous train of thought. I wasn't sure if he was now trying to discourage me or to test my resolve. I shared some stories of my prior experiences with black bears in the wilderness and described the precautions one normally takes to avoid contact. But, something in his voice and words emphasized that this place belonged to the bears.

Several months later in the Spring of 1991, Will and his wife, Barbara, were planning a trip to Las Palas and asked if I wanted to go along. Suddenly, those mountains moved from possibility to reality. I had to see what they held. This would be adventure climbing on steroids in a new and untamed area, and I needed partners that wanted to play. I organized a quick weekend trip and invited three friends: James Crump, Larry Gunn, and David Cain. James and I had been climbing together for over a decade and had just spent two weeks the previous summer climbing in the Bugaboos in Canada. Larry and Dave are local Texas climbers and had helped me put up numerous routes in the Pecos River Gorge.

After picking up James, we stopped to get groceries at the overpriced natural food store and walked away blowing the dust from our empty wallets. In true Texas yahoo style, James managed to spend all his money before we even left town. James is truly a unique phenomenon and most certainly a lifetime psychology study. He is a self-described "more-ist," which very simply stated is one who believes in the axiom that "more is always better." Several corollaries have evolved from this philosophy, mostly dealing with the mechanics of how to get more. In his quest for more, James had become the master of zero budget financing (a term which he also coined) which allows him to maximize the amount of stuff he can get with no money. A good rock climbing analogy for this philosophy would be running it out on thin slab, for which James is also a master.

That evening we pulled our circus act together, juggled the stuff into Larry's van and drove all night to arrive at La Palas, arriving by dawn. Dave pulled the graveyard shift, driving through the toughest early morning hours, arriving with the sun. The air was cool and crisp. The windows were rolled down and the fresh aromatic smell of pinon and juniper filled the van.

Suddenly, I fired off a series of commands: "OK, wake up you guys!" "Who's got the map?" "Turn left on the gravel road!" "Ok, which gravel road?" We tried to orient ourselves in the half-light and road-washed brains. "Shit!" We all belched out in synchrony as we swerved to miss a large deer stepping out in front of the moving van. Everyone was definitely awake now and despite Dave's skepticism and my cryptic scribbled directions, the road we were on led us straight to the place.

We drove up the gravel road and parked the van outside the gate surrounding a historic stucco house with rusted metal roof and painted wooden window sashes. The place was well-maintained and distinctly New Mexican territorial style. We had arrived at Las Palas, which was once a community of ranchers and loggers with more than a hundred people. The central portion of the home consisted of the original stucco walls and stone floors from an old cantina, which had been restored to create the living and dining areas. Additions to either side of the original cantina formed the bedrooms, kitchen, and bath.

Many years ago Las Palas housed woodcutters that derived their existence from harvesting the mountain timber. Long since gone, many ruins and artifacts of the old community are located within the ranch, including a small adobe building and remnant objects like bed frames and metal stove parts. It was also rumored to have been an old haunt of Billy the Kid, a famous western outlaw.

I slowly pulled on my shoes and quietly climbed out of the van. The still morning air begged for quiet - no chickens, no dogs, no cows - nothing was present to announce our arrival. It was like a great outdoor cathedral and I felt respectful of the beauty.

|

Not wanting to awaken our hosts, I approached the house cautiously and opened the gate. I was relieved when Will appeared in the doorway holding his familiar mug of coffee. It was great to meet the rest of the family, Edith and Annie, over a big country breakfast. They made us feel very much at home.

The main part of the mountain was not visible from the house. We could only guess how far the walk might be and what there was to view. We knew the ranch had an L-shaped extension up the canyon into the Lincoln National Forest, giving us more direct access to the cliffs compared to any of the public land access points. But, frankly, we had no idea how to get to the rocks. Will offered to be our trail guide for the recon but, he warned us about his bad knee. Unwittingly, we followed him through one of the most difficult brush covered, scree slope, bushwhack tortures I have sustained in recent memory. |

Eventually giving up from the pain in his knee, Will deposited us at a small spring and pool of water running in the rock. The view of the peaks from this vantage was shielded by the slopes of the drainage. The spring was located about 50 feet away from an old, unstable, hunter's tree stand. Near the spring, wired to the base of a tree, was bear feeder made from an upturned antique steel milk can with the bottom cut off. Seeing this for the first time in our journey and remembering Will’s earlier warning made me wonder about the prevalence of bears. Were they acclimated to humans and being fed? Or were they still wild, avoiding human contact? I knew that human contact and the association of humans with food sources can increase their aggression, but so can protection of something they know belongs to them, like a mother bear and her cubs.

|

Finally, just beyond the bear-feeder spring we could see a huge free-standing 300-foot spire of rock above our heads. This spire served as our landmark and the gateway to the first real view of the climbing cliffs farther up the drainage. We continued our recon past the spring and up the far-left canyon as the grade increased and the boulders became increasingly larger. Pushing on, we were convinced that few people had been to this location - at least in a very, very long time. There were no trails to follow and we continued to crash through fallen trees and loose rocks.

We reached the final steep slopes below the base of the buttress. The slopes were covered with a thick blanket of undisturbed pine needles, as if to give us one last barrier before touching the rock. |

The excitement swelled as fist and hand cracks slowly became visible through the tall pine and fir trees. Glimpses of a huge rock buttress through the tall pine and fir trees spurred our progress. Cresting the slope and traversing the base of the rock walls, we reached the base of the buttress and got the full view. We stood in amazement For a thousand feet, and strained our necks to see the features and details rising above us. We attempted to identify a weakness by which we could ascend. A prominent crack system through the upper wall appeared to be fairly continuous and contained a huge roof about halfway up the buttress. This was the buttress I had intensely focused on from the photograph. It was surreal to be in front of this massive rock I had been day dreaming about at work.

We had managed to weave and duck, scramble and scrape, and claw our way up the maze of canyons to find this buttress. The vast expanse of rock drew our gaze and the sense of possibility skyward, but the reality of the large chimney with a rotten-looking roof pulled our focus back down to the ground. We had found what we were seeking, next we needed to ascend it - that would be left for tomorrow. We slogged our way the five-or-so miles back to the ranch and assembled our gear for the ascent.

We had managed to weave and duck, scramble and scrape, and claw our way up the maze of canyons to find this buttress. The vast expanse of rock drew our gaze and the sense of possibility skyward, but the reality of the large chimney with a rotten-looking roof pulled our focus back down to the ground. We had found what we were seeking, next we needed to ascend it - that would be left for tomorrow. We slogged our way the five-or-so miles back to the ranch and assembled our gear for the ascent.

The Gump-Stumper

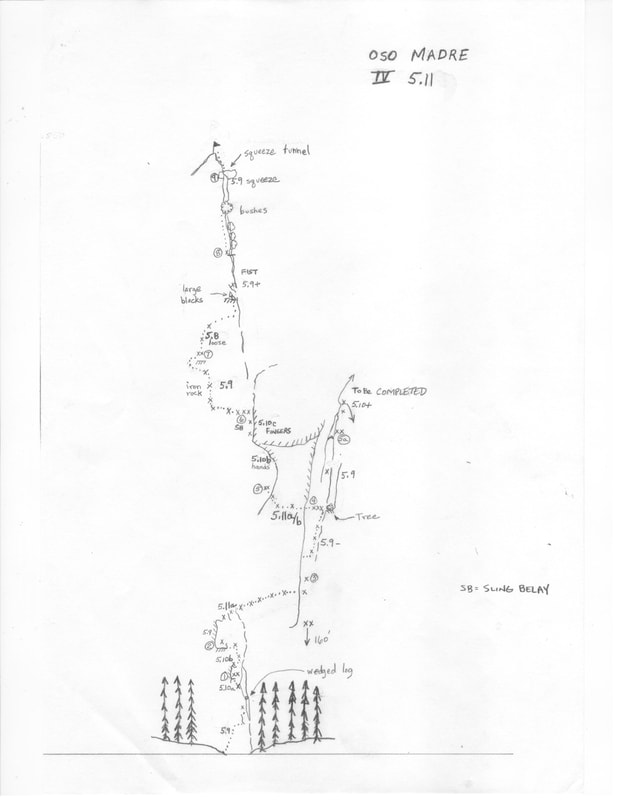

The following day our approach went more quickly, although it was far from dialed in. We set out to conquer the world with a light climbing rack and a pocket full of ambition. James took the first lead with just a handful of cams and wires. The initial section of face climbing was sloped and thin. James climbed about fifty feet before he was able to place a nut. Moving into the chimney another twenty feet above his only protection, the difficulty increased, the rock quality decreased, and the chance of getting another piece of protection was nil. James decided it was time to back off and re-evaluate our position, so he down-climbed the pitch and removed his gear. What now?

We looked around for another line. Larry and Dave had found one to the right around the buttress and there was another wide crack over to the left. There were options but uncertainty about what looked best. Finally, our Commander Crump made the call, "Lewis, go up there and drill a bolt." And so it was, we would do the original line James started up. I repeated the bottom section that James had downclimbed and drill the first bolt with a hand rig. As I was drilling, I remembered James’s familiar chant - "block that kick…block that kick" - mimicking the rhythm of the hammer hits and the excitement of a Texas football game.

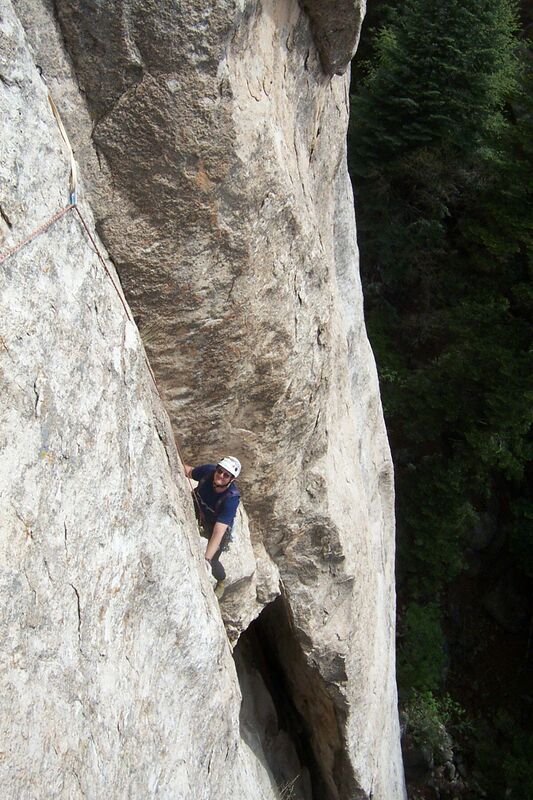

After pounding in the first bolt of the route, I climbed the chimney up another 20 feet to a wooden log jammed in the crack. At the time, the position of the log seemed peculiar, but, it was ready-made protection in an otherwise barren squeeze. A nice new sling around the log made me feel better as I squirmed around the obstacle and up another 20 feet. Roughly 120 feet off the ground, the view began to open up as I cleared the tree tops. The next point of order was the rotten roof section looming over my head.

By this time, the guys were yelling below and their enthusiasm was infectious. I reached a nice little stance and drilled the second bolt. As I hammered and turned, hammered and turned, the mantra repeated in my squirming little brain "block that kick". I was feeling great and breathed deeply with the last torque of the wrench, planting the bolt firmly in the rock.

Looking above there was a series of crusty thin inverted flakes. Everyone of them I touched would peel away like dried mud. I was starting to question the circumstances in which I had placed myself - not a mindset you want when ascending an unknown route. Then, with some relief, I saw the crack system to the left. My desire to reach it was overpowering. The moves to the crack were thin and a fall would send me on a pendulum arc into the wooden log wedged in the chimney below. After several minutes of study and contemplation, the sequence began to seem natural. Left foot way-out, right foot way-up, pull and reach up for the flat ledge. After committing to the moves, I discovered the ledge was a flake, barely on the wall. “Move, move, move” I thought, hoping that speed would defy my weight's strain on the rock's fragile attachment. I went quickly upward and into the crack. To my disappointment, the crack was also a large hollow flake and I began to doubt its integrity as I placed a cam. "Drill a bolt" was the chant from below, and so I did. Looking down at the lay of the rope, the traverse from the second bolt, and the huge log jammed in the chimney, I realized that a fall during the crux moves would have been a disaster. We ended up naming that skewer of a log "the gump stumper."

In a span of time that seemed like seconds, I belayed James up and he was now standing with me. James had a huge grin and an urgent manner. Like a child that hears the ice cream truck coming down the street, he was burning to get a move-on and start the second pitch. Before I knew what happened, James had blasted another bolt into the belay and was making the first moves onto the flake.

A large pocket at the top of the flake held a big camalot, but the bulge above it soon had James drilling another bolt. It was beginning to sound like a trend. The crack systems we could see from the ground were much less continuous than they appeared and we knew it would take more than a few bolts to put us on top.

"I hate to break up the party, but it's getting late," I cautioned James as he was contemplating the next moves above the bolt. We made the decision to retreat and come back later with some real hardware.

We played for the next hour, bringing everyone to the first belay and rapping to the ground. On the walk out, we cached about three gallons of water near the bear feeder springs in the hopes that we could save a few pounds on the next trip - which, given our level of excitement, we knew would not be too far into the future. We had discovered the area that contained decades of untapped climbing potential, but, it also had a very rugged approach that protected the crags like a mother bear protects her cubs. And so, the beginning of the Mother Bear - Oso Madre - was at hand.

We looked around for another line. Larry and Dave had found one to the right around the buttress and there was another wide crack over to the left. There were options but uncertainty about what looked best. Finally, our Commander Crump made the call, "Lewis, go up there and drill a bolt." And so it was, we would do the original line James started up. I repeated the bottom section that James had downclimbed and drill the first bolt with a hand rig. As I was drilling, I remembered James’s familiar chant - "block that kick…block that kick" - mimicking the rhythm of the hammer hits and the excitement of a Texas football game.

After pounding in the first bolt of the route, I climbed the chimney up another 20 feet to a wooden log jammed in the crack. At the time, the position of the log seemed peculiar, but, it was ready-made protection in an otherwise barren squeeze. A nice new sling around the log made me feel better as I squirmed around the obstacle and up another 20 feet. Roughly 120 feet off the ground, the view began to open up as I cleared the tree tops. The next point of order was the rotten roof section looming over my head.

By this time, the guys were yelling below and their enthusiasm was infectious. I reached a nice little stance and drilled the second bolt. As I hammered and turned, hammered and turned, the mantra repeated in my squirming little brain "block that kick". I was feeling great and breathed deeply with the last torque of the wrench, planting the bolt firmly in the rock.

Looking above there was a series of crusty thin inverted flakes. Everyone of them I touched would peel away like dried mud. I was starting to question the circumstances in which I had placed myself - not a mindset you want when ascending an unknown route. Then, with some relief, I saw the crack system to the left. My desire to reach it was overpowering. The moves to the crack were thin and a fall would send me on a pendulum arc into the wooden log wedged in the chimney below. After several minutes of study and contemplation, the sequence began to seem natural. Left foot way-out, right foot way-up, pull and reach up for the flat ledge. After committing to the moves, I discovered the ledge was a flake, barely on the wall. “Move, move, move” I thought, hoping that speed would defy my weight's strain on the rock's fragile attachment. I went quickly upward and into the crack. To my disappointment, the crack was also a large hollow flake and I began to doubt its integrity as I placed a cam. "Drill a bolt" was the chant from below, and so I did. Looking down at the lay of the rope, the traverse from the second bolt, and the huge log jammed in the chimney, I realized that a fall during the crux moves would have been a disaster. We ended up naming that skewer of a log "the gump stumper."

In a span of time that seemed like seconds, I belayed James up and he was now standing with me. James had a huge grin and an urgent manner. Like a child that hears the ice cream truck coming down the street, he was burning to get a move-on and start the second pitch. Before I knew what happened, James had blasted another bolt into the belay and was making the first moves onto the flake.

A large pocket at the top of the flake held a big camalot, but the bulge above it soon had James drilling another bolt. It was beginning to sound like a trend. The crack systems we could see from the ground were much less continuous than they appeared and we knew it would take more than a few bolts to put us on top.

"I hate to break up the party, but it's getting late," I cautioned James as he was contemplating the next moves above the bolt. We made the decision to retreat and come back later with some real hardware.

We played for the next hour, bringing everyone to the first belay and rapping to the ground. On the walk out, we cached about three gallons of water near the bear feeder springs in the hopes that we could save a few pounds on the next trip - which, given our level of excitement, we knew would not be too far into the future. We had discovered the area that contained decades of untapped climbing potential, but, it also had a very rugged approach that protected the crags like a mother bear protects her cubs. And so, the beginning of the Mother Bear - Oso Madre - was at hand.

A Precious Liquid

In a blinding rush of work, meetings, and urban funk, James and I aborted the professional mission and fled Texas like convicts in a midnight escape. We drove till dawn, pushing the envelope and stamina until we arrived at Las Palas. As we tried to dissolve the road buzz, it was impossible to get but a few moments of restless sleep. The anxiety of our pending approach epic, along with questionably-held flakes of rock on the walls above, loomed in our subconscious. We knew what the hike would be, where it went, and what it would take from our tired bodies, and this time we brought the BIG packs.

We had drills, bolts and hangers, pitons and aid gear, a two-man porta-ledge, haul bag, a free rack of cams and biners, four ropes, and 16 liters of water, that we knew was not enough for the dry conditions ahead, but, thankfully, we had 3-gallons of water stashed at the spring. Our packs were heaving with 90+ pound loads.

The approach was arduous, the weather was unseasonably hot, and we inched along the cow paths reevaluating our direction with each new gully. This time we didn't have Will's help to find our way to the bear-feeder spring, and our memories weren't clear. "Which way now?" you could hear us say through the maze of trees, rocks, and dry arroyos. The trick to the approach, we soon discovered, was to hang left at the major gully intersections, keeping out of the two minor gullies before the big spire, our landmark. When we arrived, it was early afternoon, and we soon discovered that the water cache was gone. Shit. Our water container was at the bottom of the springs with large canine teeth punctures on both sides. It had only been three weeks since our last visit. Although there was plenty of water in the springs, the bear apparently found either refreshment or entertainment in ours. We weren't sure what to be more concerned about - not having enough water, or the bear. At the moment, with 16-liters of water in our packs, the bear took the lead.

Another mile up the ravine the grade became steeper and we had to negotiate the last section of the approach, the “Obstacle Course”. There are seven wonders of the ancient world but there are eight obstacles of the Mother Bear. Because we did not have a clear path in this final mile, we were forced to negotiate large boulders, small cliffs, loose scree, and slick pine needles covering the side slopes. One obstacle known as the bowling alley contained unstable boulders that would give way and roll down the ravine onto the person below. Our awkward and heavy packs became like an anchor tied to the foot of a drowning man.

Totally exhausted, we stopped for the night above the fourth obstacle, which contains the last flat area before the base of the climb. About thirty feet in diameter, we named this area "Bear Sign Meadow" for the large quantities of stuff (i.e. residue) that the bears left covering the pine needles. Here, the walls of the ravine rose steeply on both sides - if we were to encounter a bear here, there are few alternatives for a way out. We made sure to raise our provisions into a tree.

As night settled into the dark ravine, we were saddled with an uneasy feeling associated with the limited avenues of escape. A small campfire and a can of heated chili kept me temporarily satisfied. And, in a futile display of absurdity, we both slept in the open air in our sleeping bags with a rock hammer at our side. Not long after drifting into sleep, I was awakened by James. Sitting straight up in his bag, he mumbled "What was that noise?" Groggy, I tried not to respond and carefully listened, and then, unperturbed, fell into a deep sleep deserving of the long, heavy approach and the previous evening's all-night drive. If there was a bear, I might have been the perfect sleeping-bag burrito for it.

The dawn is always cool at 7,000 feet but, we perspired as the heavy loads cut into our shoulders and hips. The last of the obstacles and the base of OSO MADRE was ours. The heavy loads made the approach much more difficult and time consuming than we anticipated.

We had drills, bolts and hangers, pitons and aid gear, a two-man porta-ledge, haul bag, a free rack of cams and biners, four ropes, and 16 liters of water, that we knew was not enough for the dry conditions ahead, but, thankfully, we had 3-gallons of water stashed at the spring. Our packs were heaving with 90+ pound loads.

The approach was arduous, the weather was unseasonably hot, and we inched along the cow paths reevaluating our direction with each new gully. This time we didn't have Will's help to find our way to the bear-feeder spring, and our memories weren't clear. "Which way now?" you could hear us say through the maze of trees, rocks, and dry arroyos. The trick to the approach, we soon discovered, was to hang left at the major gully intersections, keeping out of the two minor gullies before the big spire, our landmark. When we arrived, it was early afternoon, and we soon discovered that the water cache was gone. Shit. Our water container was at the bottom of the springs with large canine teeth punctures on both sides. It had only been three weeks since our last visit. Although there was plenty of water in the springs, the bear apparently found either refreshment or entertainment in ours. We weren't sure what to be more concerned about - not having enough water, or the bear. At the moment, with 16-liters of water in our packs, the bear took the lead.

Another mile up the ravine the grade became steeper and we had to negotiate the last section of the approach, the “Obstacle Course”. There are seven wonders of the ancient world but there are eight obstacles of the Mother Bear. Because we did not have a clear path in this final mile, we were forced to negotiate large boulders, small cliffs, loose scree, and slick pine needles covering the side slopes. One obstacle known as the bowling alley contained unstable boulders that would give way and roll down the ravine onto the person below. Our awkward and heavy packs became like an anchor tied to the foot of a drowning man.

Totally exhausted, we stopped for the night above the fourth obstacle, which contains the last flat area before the base of the climb. About thirty feet in diameter, we named this area "Bear Sign Meadow" for the large quantities of stuff (i.e. residue) that the bears left covering the pine needles. Here, the walls of the ravine rose steeply on both sides - if we were to encounter a bear here, there are few alternatives for a way out. We made sure to raise our provisions into a tree.

As night settled into the dark ravine, we were saddled with an uneasy feeling associated with the limited avenues of escape. A small campfire and a can of heated chili kept me temporarily satisfied. And, in a futile display of absurdity, we both slept in the open air in our sleeping bags with a rock hammer at our side. Not long after drifting into sleep, I was awakened by James. Sitting straight up in his bag, he mumbled "What was that noise?" Groggy, I tried not to respond and carefully listened, and then, unperturbed, fell into a deep sleep deserving of the long, heavy approach and the previous evening's all-night drive. If there was a bear, I might have been the perfect sleeping-bag burrito for it.

The dawn is always cool at 7,000 feet but, we perspired as the heavy loads cut into our shoulders and hips. The last of the obstacles and the base of OSO MADRE was ours. The heavy loads made the approach much more difficult and time consuming than we anticipated.

|

The first pitch was mine, so once again I started off with a “video belay”. It takes a while to become accustomed to leading a pitch while your belayer has one hand on the rope and the other on the video camera while watching you climb through the viewfinder. You must have a high level of trust in your climbing partner that has been developed over many years and numerous climbs. Halfway up the first pitch, I heard the crunch and crash of breaking tree branches that echoed up the narrow canyon.

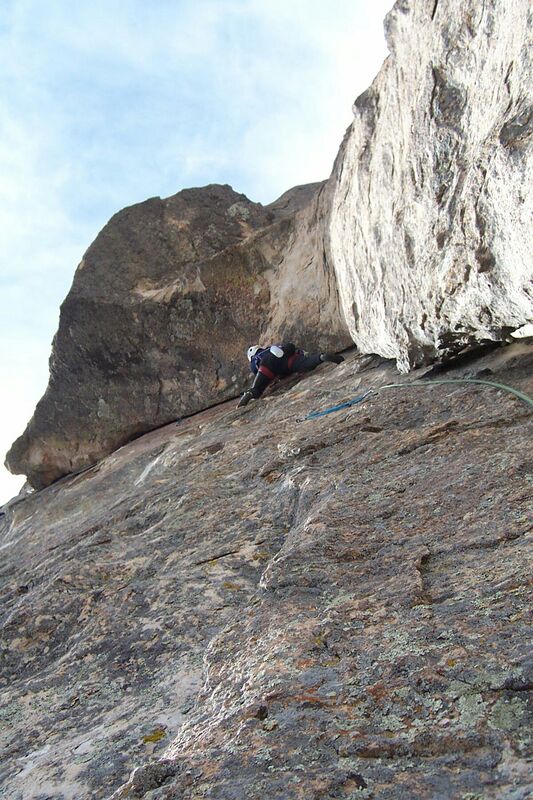

"Did you hear that?" James said from below. From my vantage point I could see some movement down the ravine and glimpses of something large and black heading our way. "Oh *&$#!" I cried. The bear appeared to be coming for an introduction but, we really didn't want to meet him. Like teenagers running from the cops, things got sketchy. "Hurry the *&#! up... and get my butt off the ground," shouted James as he started to get nervous. I rushed the pitch and hauled our gear while James soloed up the first part to a safe ledge about 20 feet off the ground. I quickly got settled and put James on belay. The noise continued in the ravine as James seconded the pitch. The noise was getting louder as the bear was crashing upward towards us through the deadwood and fallen trees. Since we and our gear were now safely out of the bear's way and had a very important mission to complete, we turned our focus back to the climb. James started the second pitch without the drill but, was soon hauling it up to protect the spectacular face climbing over the bulge. He ascended the pitch by free climbing adjacent to a seamed-up dihedral. When a good stance appeared or a sound aid placement was made, he would install a bolt. James traversed left across the face and belayed on a narrow ledge, which, fittingly, was a large flake detached in the back. Although it seemed sketchy, this turned out to be the best ledge for many pitches to come. As I seconded the pitch, I was excited by the steepness of the climbing. I knew this route would be a challenge. |

The climbing was great, the bear was way down below, and I was starting to feel really good - until I looked up and saw the crack system curl over into an overhang and stop. Not wanting to be pessimistic, I started up the dihedral in a hand sized crack which widened to six inches before it just stopped. I placed a cam in the crack at the apex, just below the point where it stopped. James was shouting encouragement as I pulled out the artillery. A four-bolt ladder across a thin and near-vertical face led to easier face climbing and longer run-outs above. By the time I reached the belay in the third crack system of the route, I was feeling the effects of heat exhaustion. The pitch took nine bolts and I was starting to fatigue. After a few moments rest, the need for water simply overpowered all other feelings and I hauled the gear. James followed the pitch and later rated the bolt ladder section 5.11.

James began the fourth pitch in a wide Hueco-Tanks-style crack with face holds to the side. Although the crack was wide, it seamed-up in the back, making the placement of protection very difficult. The route then traversed right onto beautiful Hueco holds. Some classic 5.9 face climbing led to the point where the crack reopened to accept gear. The effort of climbing and hauling, the temperature, and lack of substantive sleep had taken their toll. We decided to bivouac from our two-man portaledge at the top of the fourth pitch. A huge flock of buzzards circled overhead at dusk, but we were oblivious to their omen. We oozed like wet concrete into our nocturnal positions on the portaledge to harden overnight.

We had been eating cans of food, and other rations from the relative safety of our portaledge, and, perhaps naively and mistakenly, we had tossed the empty cans down to retrieve later upon our exit. We realized our error when we could hear the bear clanging around with our dinner cans on the rocks at the base below.

The sun finally sank over the horizon jetting wild streaks of purple and orange, a visual lullaby that soothed our nerves from the precarious perch in which we nestled high above the desert plain. The lights of Roswell were a hundred miles away.

When the morning came, I couldn't move. I had hardened sufficiently in place and our water supplies had dwindled to a solitary two-liter bottle. One and a half more pitches later and we were crying for mama. That’s when we realized that we had no water for the steep, five-mile walk out.

Rappelling from our high point about 5 and 1/2 pitches up the route, we were disappointed that the summit would not be ours. But the heat and dehydration had triggered a different kind of primal motivation. We packed the gear and drank the remainder of our water before starting the arduous trek back to the truck. It didn't take much thought to understand the climbing season was over for the Capitans.

We had been eating cans of food, and other rations from the relative safety of our portaledge, and, perhaps naively and mistakenly, we had tossed the empty cans down to retrieve later upon our exit. We realized our error when we could hear the bear clanging around with our dinner cans on the rocks at the base below.

The sun finally sank over the horizon jetting wild streaks of purple and orange, a visual lullaby that soothed our nerves from the precarious perch in which we nestled high above the desert plain. The lights of Roswell were a hundred miles away.

When the morning came, I couldn't move. I had hardened sufficiently in place and our water supplies had dwindled to a solitary two-liter bottle. One and a half more pitches later and we were crying for mama. That’s when we realized that we had no water for the steep, five-mile walk out.

Rappelling from our high point about 5 and 1/2 pitches up the route, we were disappointed that the summit would not be ours. But the heat and dehydration had triggered a different kind of primal motivation. We packed the gear and drank the remainder of our water before starting the arduous trek back to the truck. It didn't take much thought to understand the climbing season was over for the Capitans.

The Bear Becomes a Hawk

Memories of Oso Madre, had captivated our adventurous spirits and would test our patience until Fall 1991. The return was planned for the last weekend in October, about two weeks ahead of the hunter's guns. We were a little bit older and a little bit wiser, and the strategy changed. The climbing rack was trimmed and we carried a water filter to utilize the small seep that we had located near Bear Sign Meadow. To our surprise, recent rains had changed the situation and water was available less than one mile from the base of the climb.

This time James and I made arrangements for Annie to check periodically for a special rescue signal on the wall. She was concerned that we needed a method to let her know if we got into trouble. Not that we were pessimistic about our chances, but even a minor injury in the backcountry can transform a fun climb into an epic event. The signal involved stringing all our gear, sleeping bags and clothing, in a horizontal line across the wall. In addition, we would hang the bright red rainfly for the portaledge upside down with the apex pointing toward the ground.

This time James and I made arrangements for Annie to check periodically for a special rescue signal on the wall. She was concerned that we needed a method to let her know if we got into trouble. Not that we were pessimistic about our chances, but even a minor injury in the backcountry can transform a fun climb into an epic event. The signal involved stringing all our gear, sleeping bags and clothing, in a horizontal line across the wall. In addition, we would hang the bright red rainfly for the portaledge upside down with the apex pointing toward the ground.

|

After reaching the base, we trenched a two-man platform in the steep terrain and settled in for steamin’ chili and bean cuisine. It was pretty tasty and we wondered if the bear might think so also. Fortunately, the night passed without event and we awoke to the chilled fall air of dawn. The first three pitches were free climbed before hauling the "pig". This strategy worked well and we had reached the top of the fourth pitch - one pitch shy of our previous point of departure - by mid-day.

From this juncture, a different line was approached for the upper part of the climb. Instead of continuing up the previously climbed fifth pitch, James traversed left around a thin corner and across a very steep friction face. The climbing on this section is sooooo thin that fingers are useless except for balance. The friction traverse landed us in another crack system (the fourth of the route) directly below a left facing roof. A hand crack split the roof from the wall and, although steep, the pitch was totally climbable with no bolts. Loose plates were everywhere on the wall above and I got to throw another rock concert. James was showered with pebbles and grit below, but even that was not enough to stop the video camera. The upper section above the roof pinched into first knuckle finger locks and again, the crack system sputtered to a seam. From the top of the sixth pitch is a commanding view of the countryside and a blank vertical wall camp. Four bolts and a portaledge, we were sittin’ pretty watching the lights of Roswell welcome us back. Sunday was going to be a fine day and it was only four or five more pitches to the top. In the interest of speed, we decided to leave our gear at the wall camp and hand-haul a light bag. |

The seventh pitch is one of the most aesthetic on the route. James climbed out on a beautiful vertical pitch studded with iron rock and huecos. The face is very steep and drilling was done from hook placements. Before departing the wall camp, I packed the haul sack and clipped a corner of the lime green portaledge into the bolt to prevent the wind from damaging the unit.

When I reached the ledge above, James had that wild-man grin on his face. He was really jazzed and was pushing me onto the next pitch in a "go for the summit" mentality. I looked above and saw the peeling face of iron rock scales. Great! A rock buttress with psoriasis.

I kept thinking the flakes would blow out just seconds before I could complete the bolt. Fortunately, my imagination had been active and my fears substantially unfounded. The face then gave way to an overhanging fist crack (the fifth and final crack system of the route) that continued for about 25 feet and ended in a wide chimney.

When I reached the ledge above, James had that wild-man grin on his face. He was really jazzed and was pushing me onto the next pitch in a "go for the summit" mentality. I looked above and saw the peeling face of iron rock scales. Great! A rock buttress with psoriasis.

I kept thinking the flakes would blow out just seconds before I could complete the bolt. Fortunately, my imagination had been active and my fears substantially unfounded. The face then gave way to an overhanging fist crack (the fifth and final crack system of the route) that continued for about 25 feet and ended in a wide chimney.

|

As James prepared for the final pitch, we noticed a C-130 airplane flying low in the distance. As luck would have it, the video camera was damaged during the last haul, so we were unable to film this impressive, huge plane flying so low. We turned our attention back to the climb. An easy romp up a sloping ramp, James stood at the base of a forty-foot chimney. With the last push, the summit was ours.

From high above we could see that the surrounding crags jutted out of the desert like rock daggers. The formations were beautiful and much more extensive than we originally thought. The sky was clear and you’d swear that you could see Texas. Gradually the exhilaration of reaching the summit settled and we noticed, once again, the C-130 flying in what appeared to be a search pattern, this time getting closer and closer to the Capitans where we were. “They must be looking for drug runners or something," James commented. We prepared the rappel and James went first, guiding the haul sack as I lowered it. One more rappel and we reached the wall camp. |

At this point the plane had worked its way even closer, as if to be looking at us - should we not be climbing here or something? - then we arrived at the wall camp and it dawned on us - the wall camp! Annie must have been confused about the rescue signal. About this time we heard a Black Hawk helicopter coming in close to the wall for a look. “No...No...you got the wrong guys, we're not in trouble.” In unison, we waved the helicopter off with a one-armed motion but to no avail.

Quickly the rappel anchors were arranged and James took off first guiding the haulbag as I lowered it. As James traversed right under the roof the Black Hawk reappeared, this time moving within 50-feet of the wall. I could clearly see three airmen in helmets and goggles motioning to me. The co-pilot raised his hands to the side of his helmet in an inquiring manner. Again, I made a clear direct motion to wave the helicopter away. The noise from the prop wash was deafening and I was being blown off the belay stance and onto the support of my harness in the belay slings.

My attention turned to the haul bag I was lowering - there was no motion. I wondered if James had reached the next rappel.

The Black Hawk persisted and I tried once again to wave it away. The chopper kept hanging around to see what we were doing and it started to irritate and distract me. In the meantime, James had reached the belay and was attempting to stop the haulbag, as I, distracted, continued to lower it. It was futile to yell while the helicopter continued to complicate our descent. I stopped the bag, then lowered it a little more not knowing when to stop because James was around the corner, below the roof and out of sight. At the same time, James was frantically extending the leash from the bag using every piece of hardware on his harness. With the last carabiner, he just barely made the clip to the belay (no kidding). If I had continued to lower the bag past the reach of the keeper leash to the belay bolts, James would have needed to either release the bag allowing it to swing out and away from the belay, or clip it back into his harness and take the full weight of the heavy bag.

Apparently seeing that we were alive and well, the Black Hawk and crew finally decided it was Miller time so they buzzed away back to Albuquerque.

Relieved that the “rescue guys” left us, we quickly finished the final rappels to the ground. Standing on terra firma, I could hardly believe what had just happened. By the time we got to Las Palas, the rescue command was gone and Annie was hopping mad. The next hours had us explaining, apologizing and calling the rescuers to thank them for their effort. Last time it was a bear, this time it was a black hawk, but after a year and miles of road, sore muscles, and craziness, we had finally completed our mission - at least this time we had plenty of water.

Quickly the rappel anchors were arranged and James took off first guiding the haulbag as I lowered it. As James traversed right under the roof the Black Hawk reappeared, this time moving within 50-feet of the wall. I could clearly see three airmen in helmets and goggles motioning to me. The co-pilot raised his hands to the side of his helmet in an inquiring manner. Again, I made a clear direct motion to wave the helicopter away. The noise from the prop wash was deafening and I was being blown off the belay stance and onto the support of my harness in the belay slings.

My attention turned to the haul bag I was lowering - there was no motion. I wondered if James had reached the next rappel.

The Black Hawk persisted and I tried once again to wave it away. The chopper kept hanging around to see what we were doing and it started to irritate and distract me. In the meantime, James had reached the belay and was attempting to stop the haulbag, as I, distracted, continued to lower it. It was futile to yell while the helicopter continued to complicate our descent. I stopped the bag, then lowered it a little more not knowing when to stop because James was around the corner, below the roof and out of sight. At the same time, James was frantically extending the leash from the bag using every piece of hardware on his harness. With the last carabiner, he just barely made the clip to the belay (no kidding). If I had continued to lower the bag past the reach of the keeper leash to the belay bolts, James would have needed to either release the bag allowing it to swing out and away from the belay, or clip it back into his harness and take the full weight of the heavy bag.

Apparently seeing that we were alive and well, the Black Hawk and crew finally decided it was Miller time so they buzzed away back to Albuquerque.

Relieved that the “rescue guys” left us, we quickly finished the final rappels to the ground. Standing on terra firma, I could hardly believe what had just happened. By the time we got to Las Palas, the rescue command was gone and Annie was hopping mad. The next hours had us explaining, apologizing and calling the rescuers to thank them for their effort. Last time it was a bear, this time it was a black hawk, but after a year and miles of road, sore muscles, and craziness, we had finally completed our mission - at least this time we had plenty of water.