I thought I had this in the bag – or at least mostly in the bag…

I was invited to join a group of friends to climb the East Buttress of Mt. Whitney in the Sierra Nevadas. Although I am not an alpine climber, or even much of a peak-bagger, that sounded like a great opportunity – certainly not something to pass up lightly. After much internal deliberation, I said yes.

Since Mt Whitney is the highest peak in the continental U.S., I knew I needed to train. Although I was given confirmation of my participation only about a month prior to the trip (I was offered the spot of another who couldn’t go), I figured that would be enough time since I was in decent shape.

I increased training with more time at the climbing gym and hiking at altitude on nearby mountains. I also added 2-hour, before-work, sessions several days a week. Early morning sessions included hiking several thousand feet up and down nearby mountains and climbing with my husband at the local crag (which has a quite long, steep, talus approach).

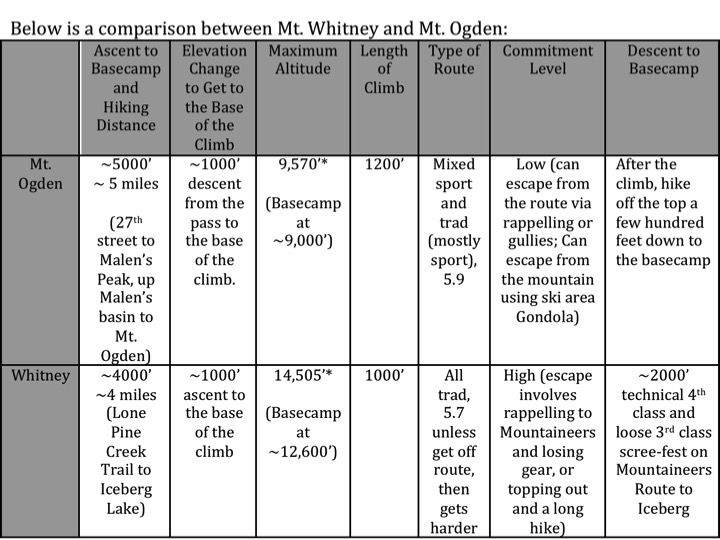

The real test came with a trial alpine run on the weekend before leaving for Whitney. We didn’t have the entire weekend just Saturday afternoon and all day Sunday. The plan was on Saturday afternoon, eat, grab all of the gear, hike nearly 5,000 feet from Ogden, Utah, up Taylor’s Canyon, to just below Mt. Ogden (which is at 9,500 feet), and camp. On Sunday, hike down about 1,000 feet to the base of an 11 pitch mixed trad/sport climb, ascend the 1,200-foot route, walk down from the peak to our campsite (retrieve the left camping gear), then hike out.

What occurred was we got out the door later than planned. My husband and I were each hauling 50+ pound packs. I had all of the climbing gear (trad rack, 70m rope, alpine draws, 2-helmets, 2-harnesses, 2 sets of shoes). He had all of the camping equipment, food (all no-cook meals), and water (we needed to haul up all of our water since it was summer and the springs were dry). We slogged our way up the steep, but maintained 3-mile trail. This took us up 2100 feet. The next 2900 feet to the top involved bushwhacking up steeper terrain and up a dry creek bed with bushes, talus, and boulders.

Because of our late start, and the slow bushwhacking, by sunset’s arrival we were about 1000 feet short of where we needed to be. We were pretty beat, and felt the darkness, tiredness, and bushwhacking was not a good combination. We decided to camp at the first decent spot. Flat ground was few and far between, but we found one tiny area that would fit our small, ultra-light, (barely) 2-person tent. My husband tested the ground and said the angle didn’t seem too bad - considering.

By the time we snacked and got settled in, it was nearly 10 p.m. We climbed into the tent, laid down, and both of us slowly slid towards the door. All night was an exercise in re-positioning. Solid sleep was fleeting.

We “woke” before sunrise and the alarm, got up, broke camp, left the non-climbing paraphernalia, and continued bushwhacking upwards in the beauty of the setting full moon and emerging dawn. It was slow going.

We finally made it to the crest, bushwhacked down towards the base of the climb, stumbling over loose rocks, holes, and bushes. With about 300 feet remaining, and even steeper terrain ahead, I called to my husband to stop.

“Rick, I very much want to climb this, but I am concerned exhaustion, combined with a steep, rocky descent with heavy packs, is an invitation for injury. We are also getting to the base of the climb nearly 2 hours later than our original plan. If the climb takes longer than we anticipate, then we will be hiking down, through all that steep crap, way later than we want.”

“I totally agree,” he replied. “Honestly, my ass is getting completely kicked by this.”

I was relieved to hear he was in the same boat. We decided to turn around and abandon the climb. I looked at the 700+ feet we just descended and thought it would be much more fun to rock-climb the face back up. It was disappointing to come all this way and not do the part I was looking forward to the most.

The 700-foot ascent and 5000 foot decent was nothing short of painful. My rubbery legs were handed to me.

I have always had a great respect for alpinists. They are a whole other breed, fit on multiple levels, have numerous technical climbing skills (rock, ice, glacier), deal with multiple, dangerous variables from weather to bad rock, to high altitude, and have excellent planning, implementation, and decision-making skills.

I have dealt with many of these elements individually as a multi-pitch trad rock climber, backpacker, back country skier, bushwhacking hiker, but this was my first attempt to string multiple items together to create an alpine climbing experience – albeit a comparatively low risk one. The experience was far more challenging than I had anticipated and it became crystal clear that the sum of alpine climbing is definitely greater than the individual parts.

Admittedly, several mistakes were made in this endeavor, including leaving later than planned, underestimating the time and effort of the approach, and, perhaps, carrying more than we should. For example, I wonder if we should have brought a shorter rope (50m?), which would have allowed us to bring a smaller rack.

Since we had not climbed this route, we decided to bring the 70m rope: (1) to string together pitches to save time (most pitches were between 30-35m); (2) The pitches have bolted anchors and the rock is mostly slab. We reasoned that we can’t build an anchor at any point along the climb (unlike with a crack climb) and, thus, are bound to the predefined pitch lengths; (3) The longest single pitch is 80m, but mostly 4th class with a short 5th class section. We would simul-climb this anyway; the next longest pitch was 50m – i.e. the minimum rope length we could bring unless we simul-climbed; (4) although there are a couple walk-off bail points, we wanted a rope long enough to rappel most of the pitches, if needed.

We considered our 60m twins, but those are heavier than the 70m. We may have gotten away with a 50m, but I was quite uncomfortable with going short. It would leave us with few escape options. I also thought, “what if that 50m pitch is 51m?” I recognize this may have been “multi-pitch crag” thinking, or perhaps even overly cautious thinking. Experienced alpinists may have approached the gear quite differently – or have different comfort levels for risk. This type of reasoning and difficult choice making further exemplifies how alpine climbing is a step beyond.

As I tripped and slid down the last mile of trail under my weakening legs, I seriously questioned whether I was ready for Whitney. Although the East Buttress climb is well within my ability - low grade (mostly 5.7, with up to 5.10 sections that can often be avoided) – I was concerned about stringing together the pieces: the long, steep approach (~4 miles, 4000 feet to camp, +1000 feet up to the base of the climb); the need to carry climbing and camping gear -including food for several days (at least we wouldn’t need water); the alpine starts; the exposure; the altitude (base camp is at ~12,000 feet and Whitney is over 14,000 ft); the weather; and the steep talus descent after a full day of climbing.

When I said yes to Whitney, I knew the seriousness of the endeavor, but my “baby step” experience with Mt. Ogden quickly revealed my weaknesses and fallacious thinking that my fairly extensive individual experiences would all add up and deliver. I was seriously considering backing out.

As time gave some distance from the Mt. Ogden experience, my muscles recovered and the need to make a decision about Mt. Whitney approached. Another two people from the original Whitney team of four had to back out, which opened a spot for my husband. We both had been training together (since the possibility of his going existed) and we decided to go for it. We would be going as a team of three with another experienced climber, but who had also not climbed Whitney.

We felt like we could take the mistakes made on our Mt. Ogden practice run and (try) not repeat them on Whitney. We were fully aware that Whitney has it’s own unique risks and attributes and could very well have its own ways to whip us, and whip us it did... (read about the Mt. Whitney Whipping).

I was invited to join a group of friends to climb the East Buttress of Mt. Whitney in the Sierra Nevadas. Although I am not an alpine climber, or even much of a peak-bagger, that sounded like a great opportunity – certainly not something to pass up lightly. After much internal deliberation, I said yes.

Since Mt Whitney is the highest peak in the continental U.S., I knew I needed to train. Although I was given confirmation of my participation only about a month prior to the trip (I was offered the spot of another who couldn’t go), I figured that would be enough time since I was in decent shape.

I increased training with more time at the climbing gym and hiking at altitude on nearby mountains. I also added 2-hour, before-work, sessions several days a week. Early morning sessions included hiking several thousand feet up and down nearby mountains and climbing with my husband at the local crag (which has a quite long, steep, talus approach).

The real test came with a trial alpine run on the weekend before leaving for Whitney. We didn’t have the entire weekend just Saturday afternoon and all day Sunday. The plan was on Saturday afternoon, eat, grab all of the gear, hike nearly 5,000 feet from Ogden, Utah, up Taylor’s Canyon, to just below Mt. Ogden (which is at 9,500 feet), and camp. On Sunday, hike down about 1,000 feet to the base of an 11 pitch mixed trad/sport climb, ascend the 1,200-foot route, walk down from the peak to our campsite (retrieve the left camping gear), then hike out.

What occurred was we got out the door later than planned. My husband and I were each hauling 50+ pound packs. I had all of the climbing gear (trad rack, 70m rope, alpine draws, 2-helmets, 2-harnesses, 2 sets of shoes). He had all of the camping equipment, food (all no-cook meals), and water (we needed to haul up all of our water since it was summer and the springs were dry). We slogged our way up the steep, but maintained 3-mile trail. This took us up 2100 feet. The next 2900 feet to the top involved bushwhacking up steeper terrain and up a dry creek bed with bushes, talus, and boulders.

Because of our late start, and the slow bushwhacking, by sunset’s arrival we were about 1000 feet short of where we needed to be. We were pretty beat, and felt the darkness, tiredness, and bushwhacking was not a good combination. We decided to camp at the first decent spot. Flat ground was few and far between, but we found one tiny area that would fit our small, ultra-light, (barely) 2-person tent. My husband tested the ground and said the angle didn’t seem too bad - considering.

By the time we snacked and got settled in, it was nearly 10 p.m. We climbed into the tent, laid down, and both of us slowly slid towards the door. All night was an exercise in re-positioning. Solid sleep was fleeting.

We “woke” before sunrise and the alarm, got up, broke camp, left the non-climbing paraphernalia, and continued bushwhacking upwards in the beauty of the setting full moon and emerging dawn. It was slow going.

We finally made it to the crest, bushwhacked down towards the base of the climb, stumbling over loose rocks, holes, and bushes. With about 300 feet remaining, and even steeper terrain ahead, I called to my husband to stop.

“Rick, I very much want to climb this, but I am concerned exhaustion, combined with a steep, rocky descent with heavy packs, is an invitation for injury. We are also getting to the base of the climb nearly 2 hours later than our original plan. If the climb takes longer than we anticipate, then we will be hiking down, through all that steep crap, way later than we want.”

“I totally agree,” he replied. “Honestly, my ass is getting completely kicked by this.”

I was relieved to hear he was in the same boat. We decided to turn around and abandon the climb. I looked at the 700+ feet we just descended and thought it would be much more fun to rock-climb the face back up. It was disappointing to come all this way and not do the part I was looking forward to the most.

The 700-foot ascent and 5000 foot decent was nothing short of painful. My rubbery legs were handed to me.

I have always had a great respect for alpinists. They are a whole other breed, fit on multiple levels, have numerous technical climbing skills (rock, ice, glacier), deal with multiple, dangerous variables from weather to bad rock, to high altitude, and have excellent planning, implementation, and decision-making skills.

I have dealt with many of these elements individually as a multi-pitch trad rock climber, backpacker, back country skier, bushwhacking hiker, but this was my first attempt to string multiple items together to create an alpine climbing experience – albeit a comparatively low risk one. The experience was far more challenging than I had anticipated and it became crystal clear that the sum of alpine climbing is definitely greater than the individual parts.

Admittedly, several mistakes were made in this endeavor, including leaving later than planned, underestimating the time and effort of the approach, and, perhaps, carrying more than we should. For example, I wonder if we should have brought a shorter rope (50m?), which would have allowed us to bring a smaller rack.

Since we had not climbed this route, we decided to bring the 70m rope: (1) to string together pitches to save time (most pitches were between 30-35m); (2) The pitches have bolted anchors and the rock is mostly slab. We reasoned that we can’t build an anchor at any point along the climb (unlike with a crack climb) and, thus, are bound to the predefined pitch lengths; (3) The longest single pitch is 80m, but mostly 4th class with a short 5th class section. We would simul-climb this anyway; the next longest pitch was 50m – i.e. the minimum rope length we could bring unless we simul-climbed; (4) although there are a couple walk-off bail points, we wanted a rope long enough to rappel most of the pitches, if needed.

We considered our 60m twins, but those are heavier than the 70m. We may have gotten away with a 50m, but I was quite uncomfortable with going short. It would leave us with few escape options. I also thought, “what if that 50m pitch is 51m?” I recognize this may have been “multi-pitch crag” thinking, or perhaps even overly cautious thinking. Experienced alpinists may have approached the gear quite differently – or have different comfort levels for risk. This type of reasoning and difficult choice making further exemplifies how alpine climbing is a step beyond.

As I tripped and slid down the last mile of trail under my weakening legs, I seriously questioned whether I was ready for Whitney. Although the East Buttress climb is well within my ability - low grade (mostly 5.7, with up to 5.10 sections that can often be avoided) – I was concerned about stringing together the pieces: the long, steep approach (~4 miles, 4000 feet to camp, +1000 feet up to the base of the climb); the need to carry climbing and camping gear -including food for several days (at least we wouldn’t need water); the alpine starts; the exposure; the altitude (base camp is at ~12,000 feet and Whitney is over 14,000 ft); the weather; and the steep talus descent after a full day of climbing.

When I said yes to Whitney, I knew the seriousness of the endeavor, but my “baby step” experience with Mt. Ogden quickly revealed my weaknesses and fallacious thinking that my fairly extensive individual experiences would all add up and deliver. I was seriously considering backing out.

As time gave some distance from the Mt. Ogden experience, my muscles recovered and the need to make a decision about Mt. Whitney approached. Another two people from the original Whitney team of four had to back out, which opened a spot for my husband. We both had been training together (since the possibility of his going existed) and we decided to go for it. We would be going as a team of three with another experienced climber, but who had also not climbed Whitney.

We felt like we could take the mistakes made on our Mt. Ogden practice run and (try) not repeat them on Whitney. We were fully aware that Whitney has it’s own unique risks and attributes and could very well have its own ways to whip us, and whip us it did... (read about the Mt. Whitney Whipping).