I had summit fever, and I had it bad. If I had been a normal teenage boy, I would have had a different kind of fever, which is not to say I didn’t, just that I had developed an obsession with mountains that seemed to override the kind of obsession that seemed to be afflicting most of my peers. At least I wasn’t at risk of getting into girl trouble, at least not by climbing mountains. There weren’t any girls climbing mountains as far as I could discern from the climbing literature available in my junior high school library, and none of the girls I knew seemed at all interested in anything that happened outside of a mall or the hallways of North Mercer Junior High. This made them remarkably uninteresting to me, aside from the fact that they were teenage girls and I was a teenage boy. But I wasn’t a normal teenage boy; for some reason, I liked mountains more than girls, and had an irresistible urge to stand on top of one.

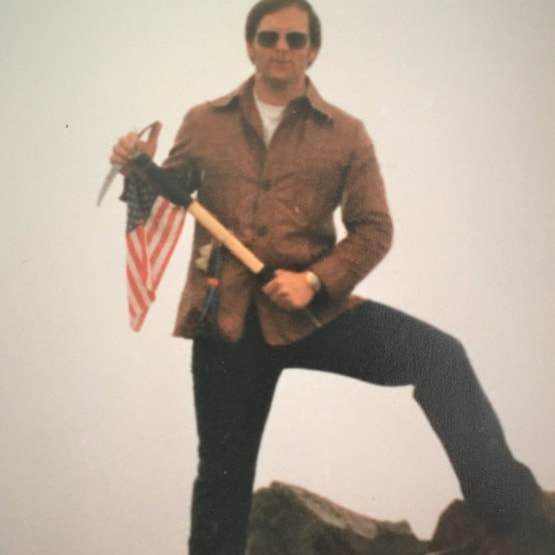

It was all Jim Whittaker’s fault. I’d been looking through National Geographic magazines for a class project when I came upon a big, glossy photo of “Big Jim” Whittaker standing on the summit of Mount Everest, posing heroically with his flag-adorned ice ax thrust upward into the gale. That could be me someday! I thought. Now I really wanted, more than anything in the world, to stand heroically on top of Mount Everest or some similar mountain, raising my banner proudly in the sky.

Of course, as a scrawny suburban seventh-grader, there were impediments to climbing a mountain, not the least of which was the fact that I was a scrawny seventh-grade kid and hardly athletic - really not mountain-climber material. And, I had no way to get to the mountains in any event. But I was inspired and determined to climb a mountain as soon as possible.

One day my dad announced we were going on a weekend drive to Mount Rainier. Could there be mountain climbing involved? I hoped there could. In advance of our trip, I scoured the school library and found a map of Mount Rainier National Park, which had a 7,000-foot-high nub of rock and scrub fir marked with an X on the map near the visitor center. It had a name and an official elevation, so it must be a mountain.

I’m not sure if my dad knew what I was thinking, but he should have known I was up to something when I brought my ice ax along. After seeing Jim Whittaker’s picture, I’d bought an ice ax at REI’s spring sale for $20. Why I was allowed to buy an ice ax, I don’t remember. My dad just shrugged. “It’s your money,” he said. “Just don’t put somebody’s eye out.”

The weather was miserable; it was cold, overcast, and windy, and Mount Rainier was completely obscured by dark clouds. We should have gone to the visitor center then gone home like everyone else, satisfied with our little pilgrimage to “the Mountain” even if we couldn’t see it. But no, that would not do, not for me. Never mind the cold wind, driving rain, and near-zero visibility. We had business to attend to. I convinced my dad that since we’d driven all the way here, we ought to hike up the trail a bit despite the spitting rain and howling gale. But after a short distance, he suggested we ought to turn around. No! We were so close! Couldn’t we at least hike up to the ridge crest? I implored. Maybe there was some snow up there where I could practice with my new ice ax, I said, grasping for a reason, any reason, why we should carry on. Please?

It was all Jim Whittaker’s fault. I’d been looking through National Geographic magazines for a class project when I came upon a big, glossy photo of “Big Jim” Whittaker standing on the summit of Mount Everest, posing heroically with his flag-adorned ice ax thrust upward into the gale. That could be me someday! I thought. Now I really wanted, more than anything in the world, to stand heroically on top of Mount Everest or some similar mountain, raising my banner proudly in the sky.

Of course, as a scrawny suburban seventh-grader, there were impediments to climbing a mountain, not the least of which was the fact that I was a scrawny seventh-grade kid and hardly athletic - really not mountain-climber material. And, I had no way to get to the mountains in any event. But I was inspired and determined to climb a mountain as soon as possible.

One day my dad announced we were going on a weekend drive to Mount Rainier. Could there be mountain climbing involved? I hoped there could. In advance of our trip, I scoured the school library and found a map of Mount Rainier National Park, which had a 7,000-foot-high nub of rock and scrub fir marked with an X on the map near the visitor center. It had a name and an official elevation, so it must be a mountain.

I’m not sure if my dad knew what I was thinking, but he should have known I was up to something when I brought my ice ax along. After seeing Jim Whittaker’s picture, I’d bought an ice ax at REI’s spring sale for $20. Why I was allowed to buy an ice ax, I don’t remember. My dad just shrugged. “It’s your money,” he said. “Just don’t put somebody’s eye out.”

The weather was miserable; it was cold, overcast, and windy, and Mount Rainier was completely obscured by dark clouds. We should have gone to the visitor center then gone home like everyone else, satisfied with our little pilgrimage to “the Mountain” even if we couldn’t see it. But no, that would not do, not for me. Never mind the cold wind, driving rain, and near-zero visibility. We had business to attend to. I convinced my dad that since we’d driven all the way here, we ought to hike up the trail a bit despite the spitting rain and howling gale. But after a short distance, he suggested we ought to turn around. No! We were so close! Couldn’t we at least hike up to the ridge crest? I implored. Maybe there was some snow up there where I could practice with my new ice ax, I said, grasping for a reason, any reason, why we should carry on. Please?

Sure, he said, probably thinking we’d hike up to the ridge crest, there would be no snow, and we would turn around. But there, in a little gully on the north side of the crest, was a little patch of late-summer snow. I spent a few minutes sliding down and practicing self-arrest, but I could tell that, short of a miracle, this was as close as I would get to climbing the mountain.

Then, as if on cue, the wind died down, the rain stopped, and the clouds parted to reveal a rocky point sticking up grail-like close above us. Was it the summit? It had to be. Couldn’t we please, please go a little farther? I begged my dad. The summit is right there!

Then, as if on cue, the wind died down, the rain stopped, and the clouds parted to reveal a rocky point sticking up grail-like close above us. Was it the summit? It had to be. Couldn’t we please, please go a little farther? I begged my dad. The summit is right there!

|

I’m not sure why my dad consented, but he indulged my little fantasy and said we could go a little farther as long as it wasn’t raining. Yes! I hurried along the trail to where a broad scree gully invited us to leave the trail and scramble upward into the mist. The gully led to a windswept saddle, from where a short scree traverse seemed to lead to the base of a rock gully. This way, I pointed, then vanished over the saddle before anybody could say otherwise. My dad and little brother reached the saddle just as a dark cloud blew over and it started raining hard. My dad yelled something that I conveniently could not hear over the wind. I just grinned back at him, pointed toward the summit, and kept climbing.

The gully ended at a short wall of shattered rock. I picked my way up the flinty choss and there I was, standing alone, atop a rocky point no bigger than our family’s kitchen table, enveloped in thick fog, unable to see anything around me. A huge drop-off loomed one step in front of me, invisible yet frighteningly close. Despite the wind and the enveloping clouds, it was intoxicatingly perilous to stand there on that tiny peak. At least, I thought so. The rest of the team soon arrived on the summit. They were not so enraptured. |

Although I was the de facto leader of our little expedition, having led my team to the windswept summit of this improbable, dangerous peak, my dad pulled rank. He insisted we descend immediately. No, I insisted. Something had to be done first, a formality that we, as mountaineers, were obliged to observe.

I reached into my pack, pulled out a small American flag, and tied it to my ice ax. I pulled my Kodak Instamatic camera out of my vest pocket and handed it to my dad, then stood on the highest point and held my ice ax proudly up into the gale.

For a moment, I felt like Jim Whittaker on the summit of Mount Everest, even if I looked like a total dork.

I reached into my pack, pulled out a small American flag, and tied it to my ice ax. I pulled my Kodak Instamatic camera out of my vest pocket and handed it to my dad, then stood on the highest point and held my ice ax proudly up into the gale.

For a moment, I felt like Jim Whittaker on the summit of Mount Everest, even if I looked like a total dork.

Jeff went on to climb many more mountains over the years and authored several guidebooks including "Climbing Washington's Mountains." Originally published in 2001, it has finally been updated and is available at: http://falcon.com/books/9781493056439.