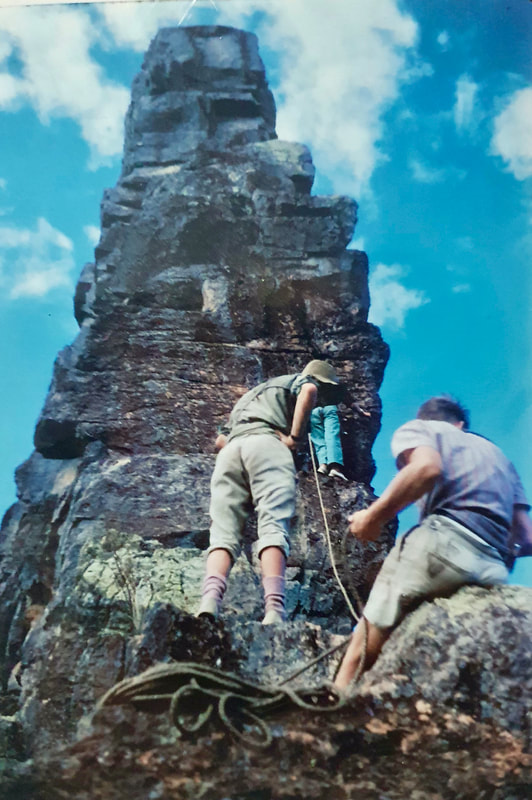

Climbing in Australia has changed considerably since the Sydney Rockclimbing Club was formed in 1951. In the early days, a climbing kit consisted of a pair of Dunlop sandshoes, a 1 ¾ inch sisal rope, makeshift slings, and pebbles for use as chocks."

- Rachel Gleeson, 50 Years of the Sydney Rockclimbing Club, Thrutch, 50th Anniversary Issue, 2001, P.1

|

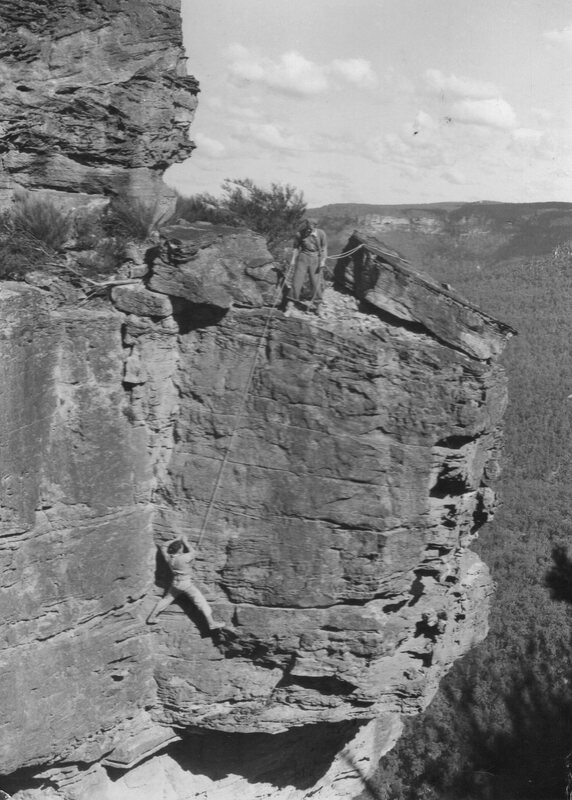

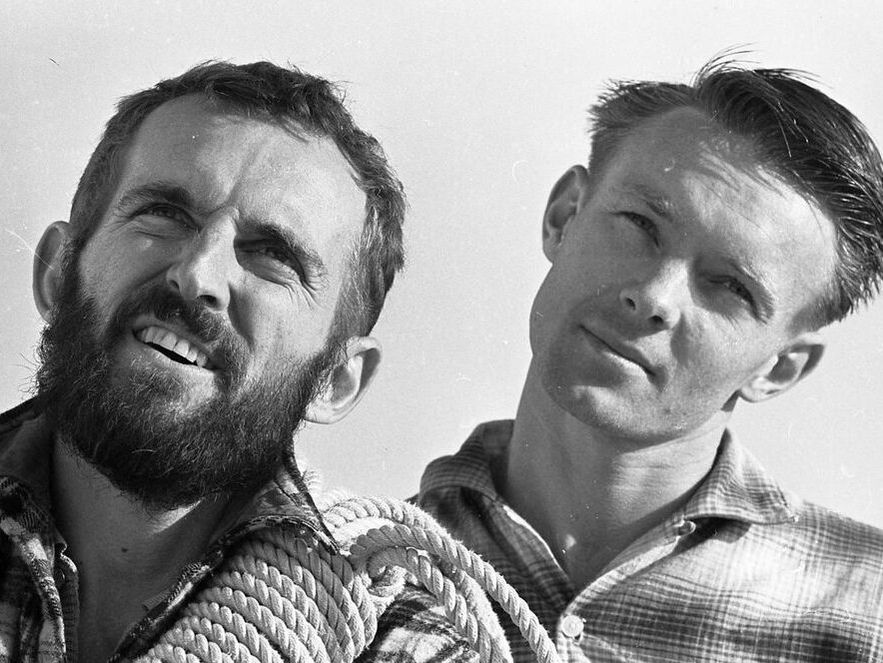

On every continent rock climbing begins somewhere. For Australia it was with natural fibre ropes and slings, steel carabiners of dubious quality, inferior European soft steel pitons, a bowline round the waist tie-in, sandshoe or hobnail/Vibram soled boots complemented by loads of courage supported by the dictum that "the leader never falls." It also started with a small band of bold people willing to climb with such gloriously primitive equipment and methods; their number included Dave Roots.

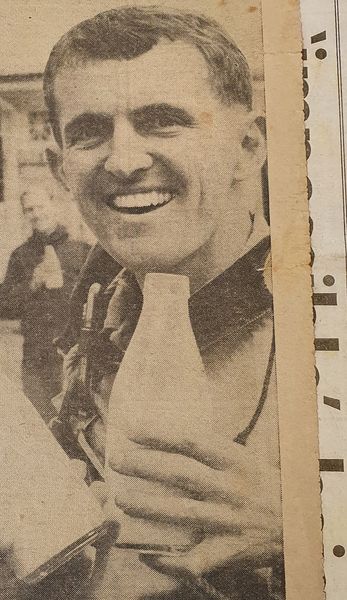

David Roots was one of New South Wales' foremost climbers to emerge in the 1950's post-war period. Dave evolved from the family activity of bushwalking (his father, Wally Roots was a renowned bushwalker) into climbing. Back in the day, both activities were pursued purely for their intrinsic adventure and enjoyment rather than occupying a space in a guidebook, which did not exist then. As a result, many first ascents were lost to time. Around 1950, some of Sydney’s bushwalkers were starting to take an interest in climbing steeper peaks and walls as an adjunct to their walking. An influx of British climbing books such as Colin Kirkus’ Let’s Go Climbing helped to stimulate this pursuit. As interest grew, several members of the Rucksack Bushwalkers endeavoured to implement a climbing section under the aegis of the club. While this attempt failed, undeterred, the Sydney Rockclimbing Club (SRC) held its inaugural meeting as a separate entity at a suburban home in the middle of 1951. |

Dave Roots arrived at a meeting two or three months after the formation of the club, when it was held in a hired room in a city building."

- Russ Kippax, The Formation of the Sydney Rockclimbing Club, P.3

Scant records show that Dave was elected President of the club in 1958 and later made an Honorary Life Member. He received further recognition from the climbing community when he was made the first Patron of the Macquarie University Climbing Club. From such beginnings legends are made.

Though the list of Dave’s first ascent portfolio appears slim, there are some absolute classics such as The Mantleshelf (13/5.5) on the Three Sisters at Katoomba and Fuddy Duddy (15/5.7) on the nearby Narrowneck peninsula. Less well known are Tooth & Nail (now 18/5.10a) and Terrier I (14/5.6) in the Rhum Dhu area; these two climbs are of special significance, as will be revealed later.

Many of Dave's other first ascents in the Blue Mountains, Wolgan Valley, and the Warrumbungles fell through the cracks of time and informal record-keeping and have probably since been claimed by others in subsequent eras.

Though the list of Dave’s first ascent portfolio appears slim, there are some absolute classics such as The Mantleshelf (13/5.5) on the Three Sisters at Katoomba and Fuddy Duddy (15/5.7) on the nearby Narrowneck peninsula. Less well known are Tooth & Nail (now 18/5.10a) and Terrier I (14/5.6) in the Rhum Dhu area; these two climbs are of special significance, as will be revealed later.

Many of Dave's other first ascents in the Blue Mountains, Wolgan Valley, and the Warrumbungles fell through the cracks of time and informal record-keeping and have probably since been claimed by others in subsequent eras.

[Dave] explained that when they climbed (almost every weekend) they usually only did first ascents – but they never bothered to record them. It was only after 10 years of climbing that he stopped using trees or suspect piton runners and began instead to use chocks and bolts."

- Roger Z A Collison in A Guide to the Three Sisters – Katoomba, An Interview with Dave Roots, 1987, P. 29

Despite the lack of formally listed climbs, it as well to remember that:

Such climbers have formed the framework for future generations and the progression of climbing [in NSW and probably Australia itself].”

- Bruce Cameron in Rock, Autumn 2012, Well Trodden Roots, Pages 36-39

Dave’s climbs that did make the guidebooks are listed below.

Warrumbungles:

BreadKnife

North Arete 138 Metres 13 1956

Skyline Traverse 291 Metres 14 1956

Warrumbungles:

BreadKnife

North Arete 138 Metres 13 1956

Skyline Traverse 291 Metres 14 1956

Blue Mountains:

Glenbrook Gorge

Jack Murphys Climb 60 Metres 12 1956

Cancer 20 Metres 13 1962

The Three Sisters

The Mantleshelf 25 Metres 13 1953

The Rhum Dhu

Terrier One 95 Metres 16 1961

Tooth and Nail 65 Metres 18 1961

Narrowneck

Fuddy Duddy 95 Metres 15 1960

March Fly 55 Metres 16 1960

Mt Banks

Original Route 300 Metres 13 ?

Coronation Crack 200 Metres 13 1953

Wolgan Valley:

Donkey Mountain

The Roots Chimney V. Diff (Very Difficult)

Glenbrook Gorge

Jack Murphys Climb 60 Metres 12 1956

Cancer 20 Metres 13 1962

The Three Sisters

The Mantleshelf 25 Metres 13 1953

The Rhum Dhu

Terrier One 95 Metres 16 1961

Tooth and Nail 65 Metres 18 1961

Narrowneck

Fuddy Duddy 95 Metres 15 1960

March Fly 55 Metres 16 1960

Mt Banks

Original Route 300 Metres 13 ?

Coronation Crack 200 Metres 13 1953

Wolgan Valley:

Donkey Mountain

The Roots Chimney V. Diff (Very Difficult)

The Mantleshelf

The climb that really stands out from the list is The Mantleshelf, a short but exposed route on the First Sister, the closest of the Three Sisters to the main plateau at Katoomba. Back in the day most climbers cut their teeth on the various routes offered by The Sisters:

[They} have attracted climbers from early times and their first ascent is unknown, probably by Captain Cook in 1770.”

- John Ewbank, Rockclimbs in the Blue Mountains, 1967, P. 46

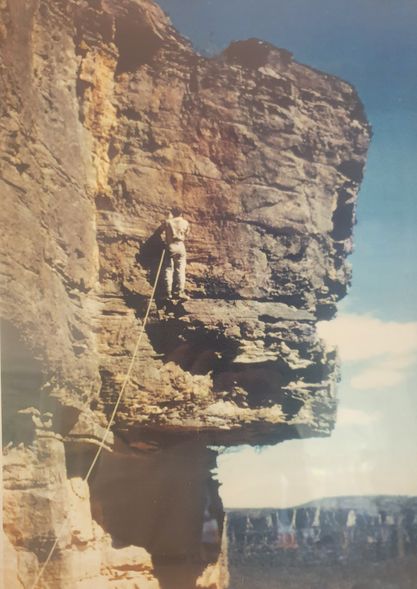

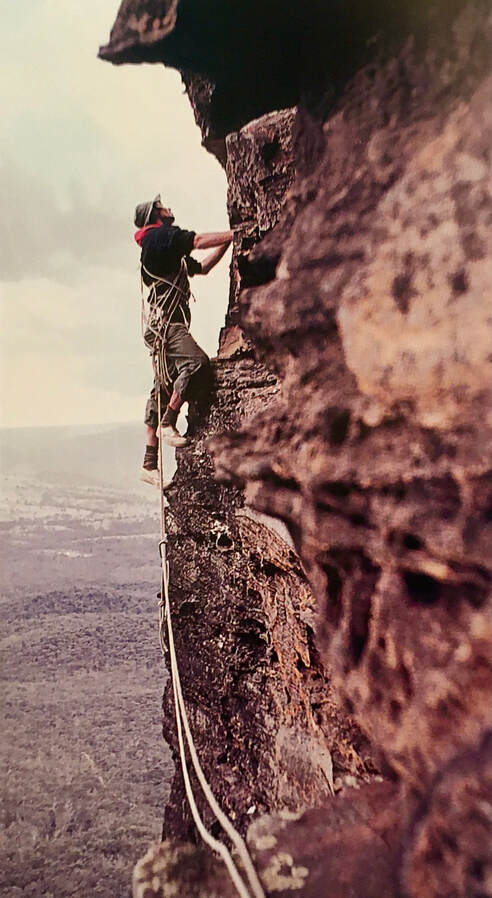

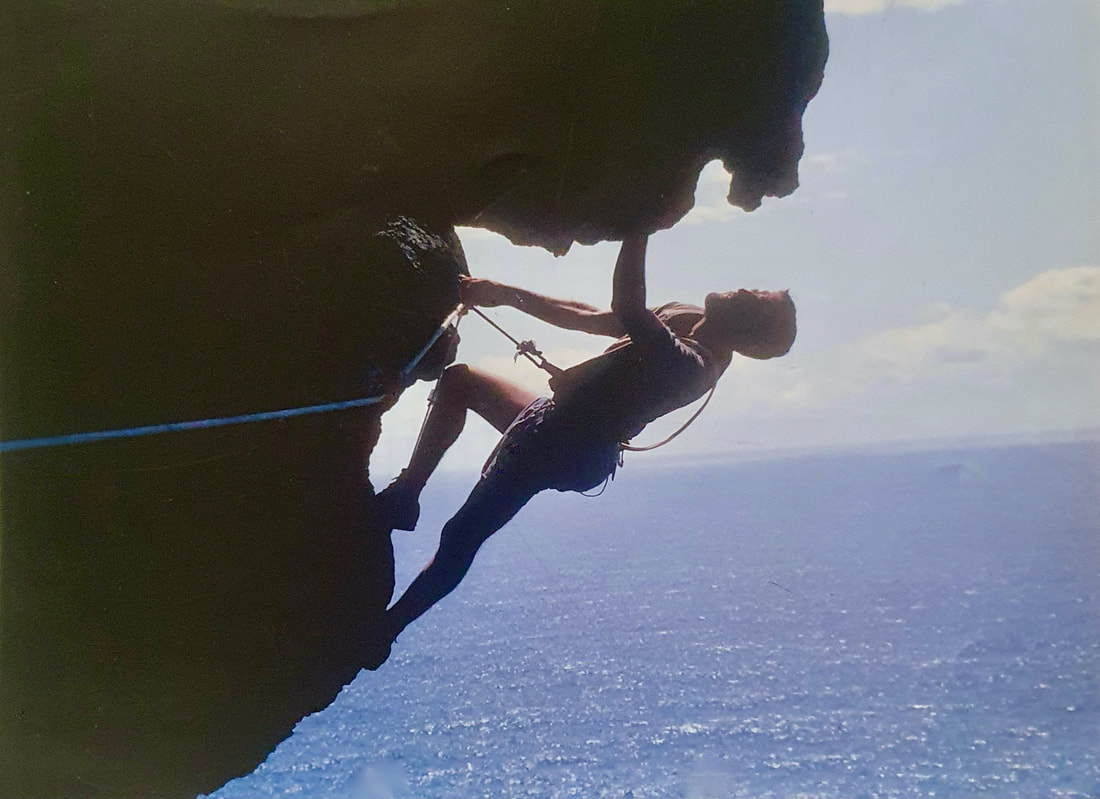

The Mantleshelf is a gloriously exposed climb. After crossing a tourist bridge to the cosily named Honeymoon Point, a belay is set up using the guard rail. Once a climber steps across the rail to begin the climb they are faced with a smooth yellow, relatively unprotected overhanging sandstone wall with over 200 metres of air looming below their feet. Eventually, by moving diagonally right across the void, a block is reached that juts out at the bottom of a right-angled corner – the mantleshelf. Above the mantleshelf is a fine, steep wall that leads to the safety of a big ledge. All of this can be observed from the stairs leading down to the bridge. Ewbank in his guidebook acerbically and succinctly described this climb as “a fine climb exposed to both thin air, and far worse, many stupid yobs."

Since The Mantleshelf is close to a large tourist car park, it was always worth a drop in for a quick climb, especially when leaving early from climbing further up in the mountains. Having done The Mantleshelf numerous times, I lost count of the number of times that I was asked by onlookers if I was looking for birds’ eggs or maybe if I had lost my marbles. But the classic experience was when an incensed nursing matron yelled across the defile gap initiating this exchange with me while I was leading:

Matron: I’m a hospital matron, if you fall off and hurt yourself you had better not come to my hospital!

Me: Lady, if I fall off and hurt myself, I don’t want to come to your hospital!

Matron: I’m a hospital matron, if you fall off and hurt yourself you had better not come to my hospital!

Me: Lady, if I fall off and hurt myself, I don’t want to come to your hospital!

Fuddy Duddy

The Mantleshelf is such a great climb but, unfortunately, it is now banned owing to the loose rock on other parts of "The Sisters" that can fall onto a public stairway (the Giant Staircase) that leads down into the valley. But Dave’s climb, Fuddy Duddy, on the nearby Narrowneck peninsula is open for all comers – if they dare?

Dave was hardly a "fuddy duddy" but he and Russ Kippax were viewed as "elderly" by the mostly younger generation when they made the first ascent of this climb at Narrowneck. Legend has it that they came up with the name Fuddy Duddy to get up the nose of the same climbers who thought that they were not up to the task.

The route has changed somewhat from the first ascent as a large block, essentially its first pitch, slid downhill in the 1970’s during torrential rain. I still have memories of belaying at the top of the first pitch below the right-angled corner on a horizontal break with an incipient crack on the left. This crack defined the right-hand side of the block that slipped downhill. From here the steep, wide corner crack looms above.

Dave was hardly a "fuddy duddy" but he and Russ Kippax were viewed as "elderly" by the mostly younger generation when they made the first ascent of this climb at Narrowneck. Legend has it that they came up with the name Fuddy Duddy to get up the nose of the same climbers who thought that they were not up to the task.

The route has changed somewhat from the first ascent as a large block, essentially its first pitch, slid downhill in the 1970’s during torrential rain. I still have memories of belaying at the top of the first pitch below the right-angled corner on a horizontal break with an incipient crack on the left. This crack defined the right-hand side of the block that slipped downhill. From here the steep, wide corner crack looms above.

Having never climbed an off-width crack, I felt out of my depth when contemplating Fuddy’s huge wide corner crack looming above the detached block belay. Somewhat daunted, I spent a long time on this pitch as the climbing was very exposed and challenging for the grade. As it is a long pitch there was much relief when I finally arrived at the belay ledge and was chuffed with myself for leading it."

- Simon Sharples – Blue Mountains Climber

But Fuddy Duddy throws down a final gauntlet with a varied and interesting third pitch. Again, Simon relates his experience on this section.

It begins with a stiff boulder problem followed by a ramble up to a long and deep chimney. Initially the chimney is easy and enjoyable, but close to the top, it narrows into a tight constriction. Moving up into it, unsurprisingly I got stuck. After a lot of swearing and squirming I finally got through the squeeze and cruised up the remainder of the chimney to top out on this Roots/Kippax classic, older and wiser."

Tooth & Nail and Terrier I

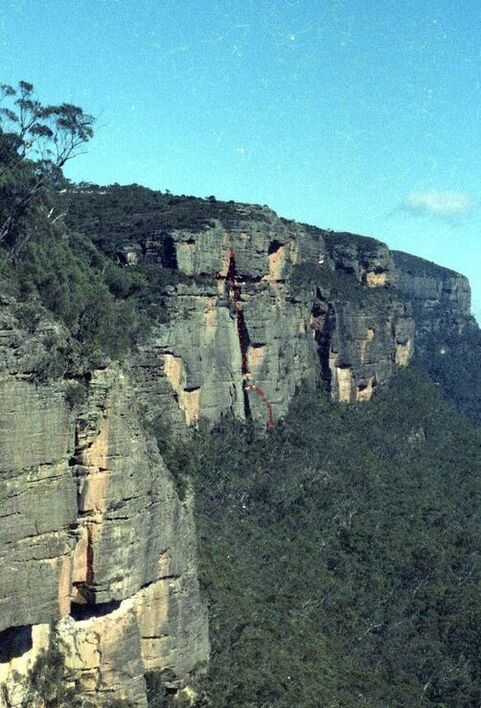

Narrowneck is a long peninsula extending out from the main Katoomba plateau. Where the peninsula joins the plateau, its east side is buttressed by the vertical sandpit of a feature called Dogface or the Giant Landslide. On its other side, the Rhum Dhu area sidles westward with the majestic Boars Head formation sitting atop an impressive line of cliffs. It is here that Dave put up another one of his famous climbs – Tooth & Nail (15 & M2 now 18/5.10a). Climbed in 1964, again with Russ Kippax, it ascends a long vertical sweep of wall leading up to the Boars Head.

… a fine climb, exposed and commanding”.

- John Ewbank, Ibid, P. 63

|

Although I looked at it from Narrowneck, and put it on my hit list, fear and trepidation made me avoid it for many years. By the time I thought I was up to the challenge, my interests had been directed elsewhere. This climb though has a special place in Blue Mountains climbing as it was the first to use “extensive artificial aids”. (Bryden Allen, ROCK-CLIMBS of NSW, 1963, P. 38)

But Dave, in the company of Les Tattersall, has another nearby route that also has a special claim to fame. [Terrier I] was the first climb to use expansion bolts [in the Blue Mountains]. Several are used and are useful as belays and runners”. |

While terriers are dogs, they were also a type of socket bolt that are now essentially obsolete. A hole is drilled, and the socket is placed into it. The socket has an internal screw thread that allows a 3/8-inch eye bolt to be fitted. While Dave pioneered bolts in the Blue Mountains, this type was soon superseded by Bryden Allen’s development of the infamous carrot. But perhaps Dave’s greatest achievement lies to the east of Australia’s coast.

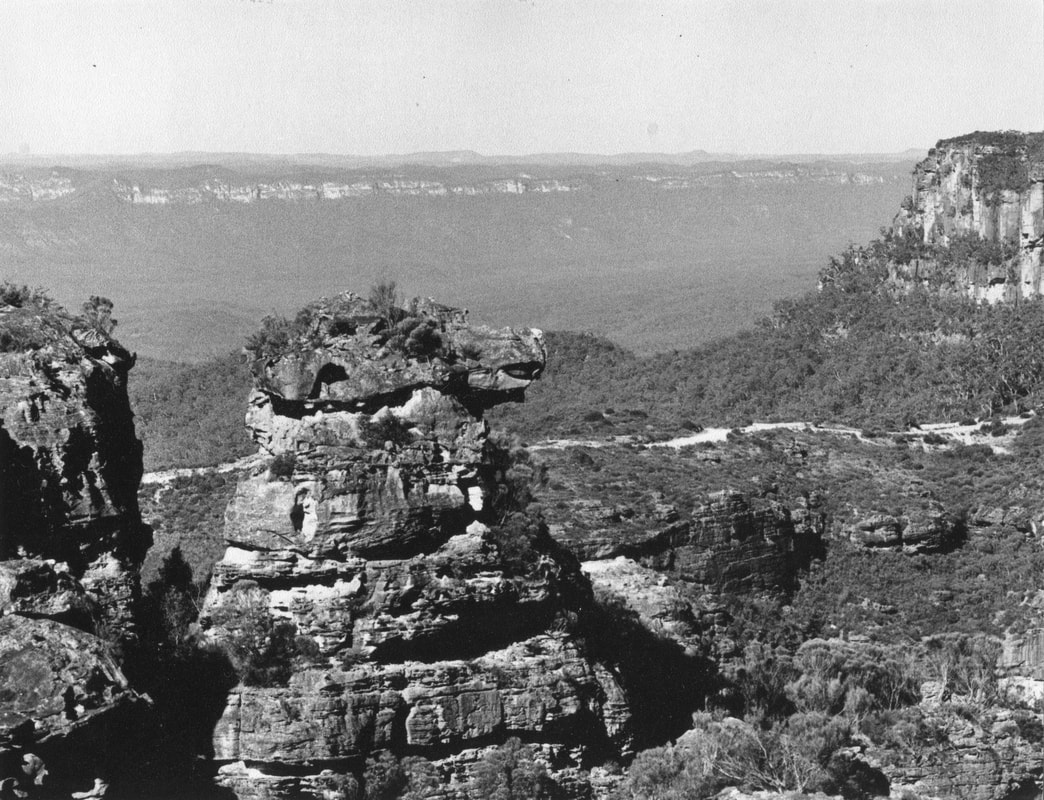

Balls Pyramid

Balls Pyramid was discovered by Lieutenant Lidgbird Ball in February 1788 as he sailed from Sydney to Norfolk Island. Although it is a hostile, isolated rock, there were several early attempts to reach its summit mainly by sailors and various adventurers with more daring than skills. The first modern climbers to climb on the Pyramid were Dave Roots and Rick Higgins.

Rick Higgins was the instigator; in 1959 he had come across a photo of the Pyramid in a women’s magazine, the Australian Women's Weekly and was instantly hooked. While the seed was sown, it remained dormant, waiting for the right climbing partner to come along.

In March 1962 Rick and Dave met. Rick was with a large group abseiling down Kalang Falls into the Kanangra Deep, located in wild country south of Katoomba. One of their number slipped on wet rock towards the bottom, falling 10 metres and injuring his legs. Rick and a few others climbed out to get help. Many turned up to assist but it was Dave and Russ Kippax who planned and supervised this difficult rescue.

Rick Higgins was the instigator; in 1959 he had come across a photo of the Pyramid in a women’s magazine, the Australian Women's Weekly and was instantly hooked. While the seed was sown, it remained dormant, waiting for the right climbing partner to come along.

In March 1962 Rick and Dave met. Rick was with a large group abseiling down Kalang Falls into the Kanangra Deep, located in wild country south of Katoomba. One of their number slipped on wet rock towards the bottom, falling 10 metres and injuring his legs. Rick and a few others climbed out to get help. Many turned up to assist but it was Dave and Russ Kippax who planned and supervised this difficult rescue.

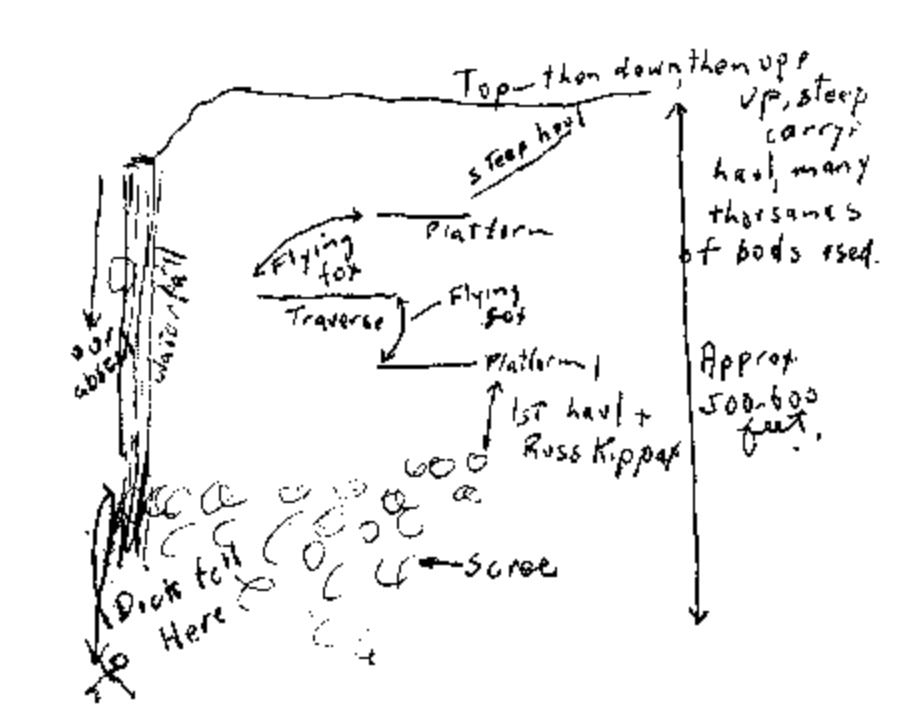

[Dave and Russ] concocted an elaborate system of flying foxes, block and tackles, pulleys, etc. A strait jacket like stretcher was then buckled around the [patient] and he was hoisted in stages to the top of the cliff where nearly 100 volunteers… took turns carrying him to safety."

- Peter Hinton, Sydney University Bush Walkers - SUBW Logbook 2, 1962, Ibid above

Although Rick had found an older and more experienced climbing partner in Dave, a year passed before he showed him the Pyramid photo. While both were smitten, all was not plain sailing to get to their isolated, vertical, and unclimbed destination; it was not until March 1964 an attempt could be made. The easiest access then was to fly to the nearby Lord Howe Island (by flying boat), then hire a fishing boat for transport to the pinnacle. While this sounds easy there was a reluctance shown by the islanders to transport climbers to the rock.

It turned out that an earlier group in 1962 had sullied the waters somewhat. In the end Dave and Rick were given permission to land for a day only. They were able to climb up about 200 metres, but had to retreat to keep the promise that they had made to descend to the boat way before sunset. They returned about a week later and made their way in the day allowed above Gannet Green, still somewhat short of the twin peaked Winklesteins Steeple. But lessons had been learnt.

It turned out that an earlier group in 1962 had sullied the waters somewhat. In the end Dave and Rick were given permission to land for a day only. They were able to climb up about 200 metres, but had to retreat to keep the promise that they had made to descend to the boat way before sunset. They returned about a week later and made their way in the day allowed above Gannet Green, still somewhat short of the twin peaked Winklesteins Steeple. But lessons had been learnt.

Before the year ended, as luck might have it, a scout expedition was organised and Rick and Dave, based on their experience, were invited to join it. This time they were on a boat that would take the group from Sydney to the Pyramid, thus avoiding the early problems associated with the reliance on the islanders’ boats. Four days after a successful landing, the group reached Winklesteins Steeple before calling it a day.

I found myself on the narrowest of perches … on top of a spire 400 metres above the water. Daylight was going. The others came up. We spent a sleepless night tormented by centipedes, buffeted by gusts and bolted to the rock [on what was later named Winklesteins Steeple]."

- Dave Lambert in Dick Smith (Ed), Balls Pyramid: 50 Years of Exploration, 2015, P. 58

With steep terrain ahead and winds gusting up to 80 kph (50 mph), the decision was made by to descend.

Only two months later Bryden Allen, John Davis, Jack Pettigrew, and Dave Witham landed on the Pyramid and reached the summit on St. Valentine's Day in 1965. This team was able to learn from the many problems and solutions that Dave and Rick’s earlier incursions had experienced and overcome. For Bryden and subsequent expeditions the principal outcome was that local boat skipper, Clive Wilson, was prepared to take prospective climbers and leave them on the Pyramid for many days.

But Dave has another claim to fame. On the way down, while walking across Gannet Green, he found a dead specimen of the Lord Howe Island phasmid or stick insect. Believed to be extinct on the island after rats had escaped from a foundering vessel in 1918, the finding was a scientific revelation. This discovery was affirmed by Jim Smith, a trained biologist climbing with another expedition in 1969, when he found two carapaces of the insect that had been shed close to the summit. An unfortunate by-product of the discovery was the banning of recreational climbing on Balls Pyramid since 1986. Ultimately, these early discoveries by climbers have been somewhat diminished and eclipsed by the fanfare that surrounded the discovery of living specimens on a melaleuca tree below Gannet Green by scientists in 2001.

Unfortunately, I never got to climb with Dave, though his name had been up there in lights when I was an aspiring climber. Eventually, I shook my way up The Mantleshelf and Fuddy Duddy, and looked across longingly at Tooth & Nail. I still dream of doing his classic route up Mount Banks, the longest route in the Blue Mountains.

The last occasion I saw him was at the Balls Pyramid book launch in 2016 where he brought along his boxed specimen of the Phasmid that he found in 1964. Dave circulated freely, talking and laughing with the gathered climbers and kindly exhibited his amazing find. Rick Higgins, Dave’s long-time friend and climbing partner says:

Only two months later Bryden Allen, John Davis, Jack Pettigrew, and Dave Witham landed on the Pyramid and reached the summit on St. Valentine's Day in 1965. This team was able to learn from the many problems and solutions that Dave and Rick’s earlier incursions had experienced and overcome. For Bryden and subsequent expeditions the principal outcome was that local boat skipper, Clive Wilson, was prepared to take prospective climbers and leave them on the Pyramid for many days.

But Dave has another claim to fame. On the way down, while walking across Gannet Green, he found a dead specimen of the Lord Howe Island phasmid or stick insect. Believed to be extinct on the island after rats had escaped from a foundering vessel in 1918, the finding was a scientific revelation. This discovery was affirmed by Jim Smith, a trained biologist climbing with another expedition in 1969, when he found two carapaces of the insect that had been shed close to the summit. An unfortunate by-product of the discovery was the banning of recreational climbing on Balls Pyramid since 1986. Ultimately, these early discoveries by climbers have been somewhat diminished and eclipsed by the fanfare that surrounded the discovery of living specimens on a melaleuca tree below Gannet Green by scientists in 2001.

Unfortunately, I never got to climb with Dave, though his name had been up there in lights when I was an aspiring climber. Eventually, I shook my way up The Mantleshelf and Fuddy Duddy, and looked across longingly at Tooth & Nail. I still dream of doing his classic route up Mount Banks, the longest route in the Blue Mountains.

The last occasion I saw him was at the Balls Pyramid book launch in 2016 where he brought along his boxed specimen of the Phasmid that he found in 1964. Dave circulated freely, talking and laughing with the gathered climbers and kindly exhibited his amazing find. Rick Higgins, Dave’s long-time friend and climbing partner says:

Dave and I were almost lifelong friends. We met at the bottom of Kalang Falls on [the Kanangra rescue] along with John Davis, whom I also started a very close, lifelong friendship. The three of us did some wonderful trips over the years including a month’s climbing on Baffin Island and a trip into the Canadian Rockies. The first Balls Pyramid trip was of course just sheer magic. I was always the organizer and Dave the selfless enthusiast. Our partnership over the years was always on planning our next trip. Dave never lost his sense of still being a young boy, always enticed by the possible magic of whatever we schemed up. And he exuded this character throughout his entire life."

Cave Diving

|

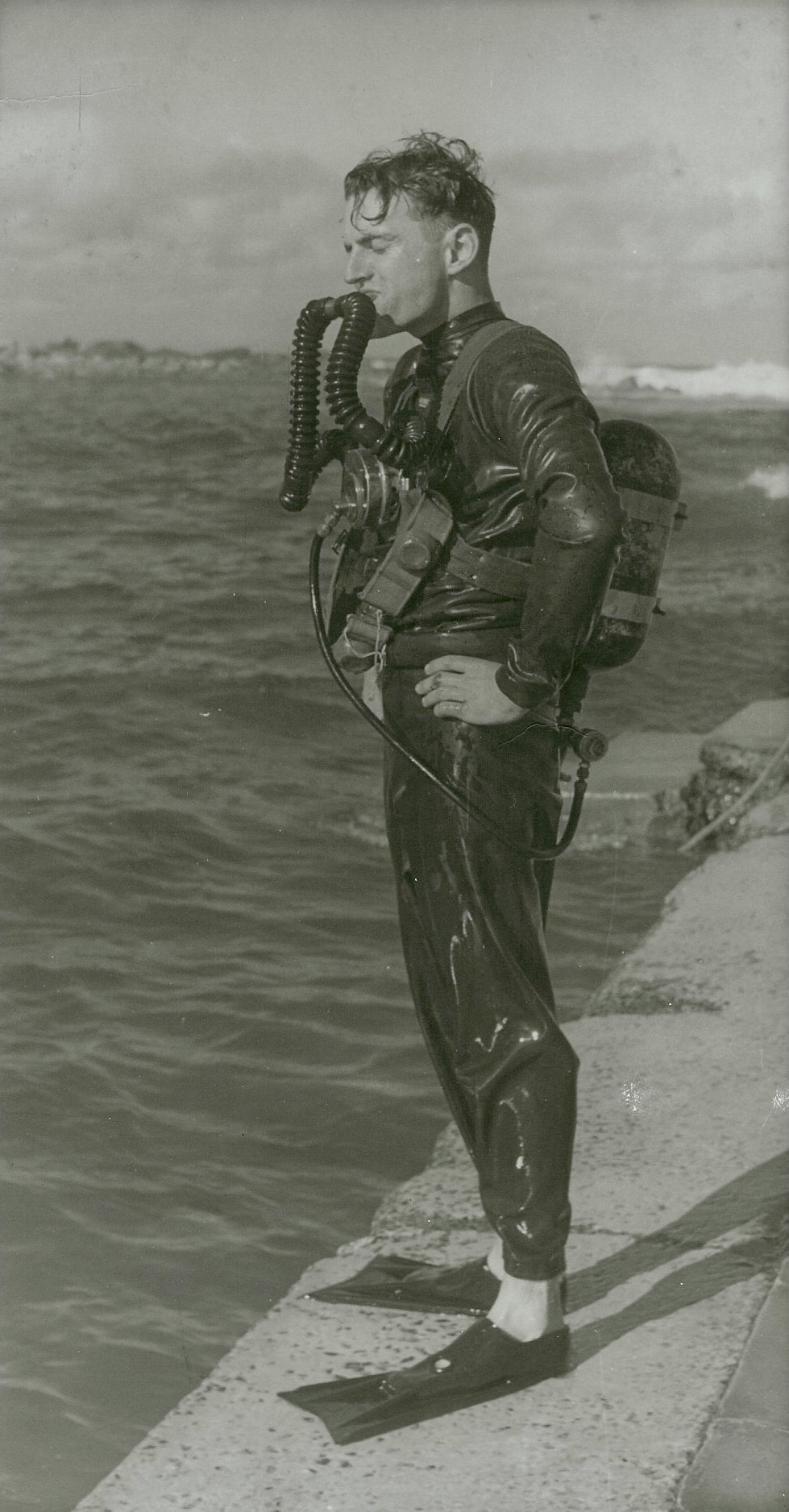

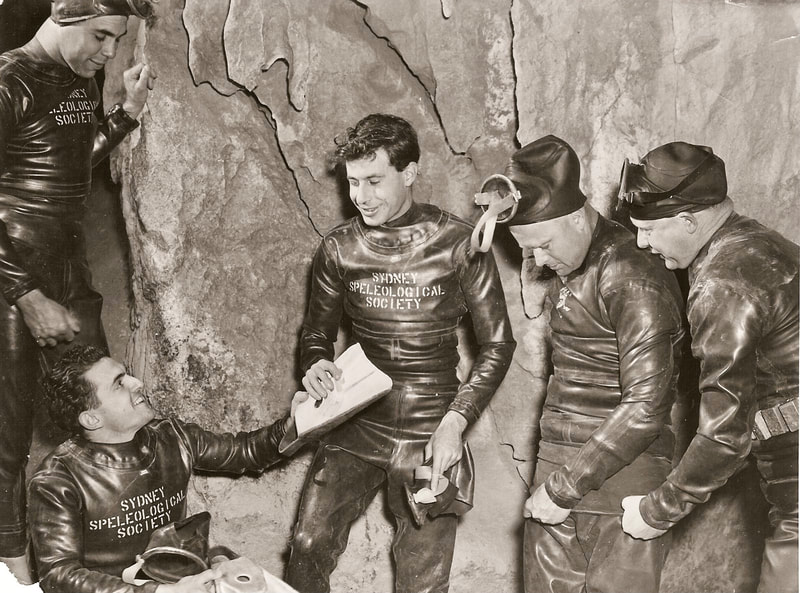

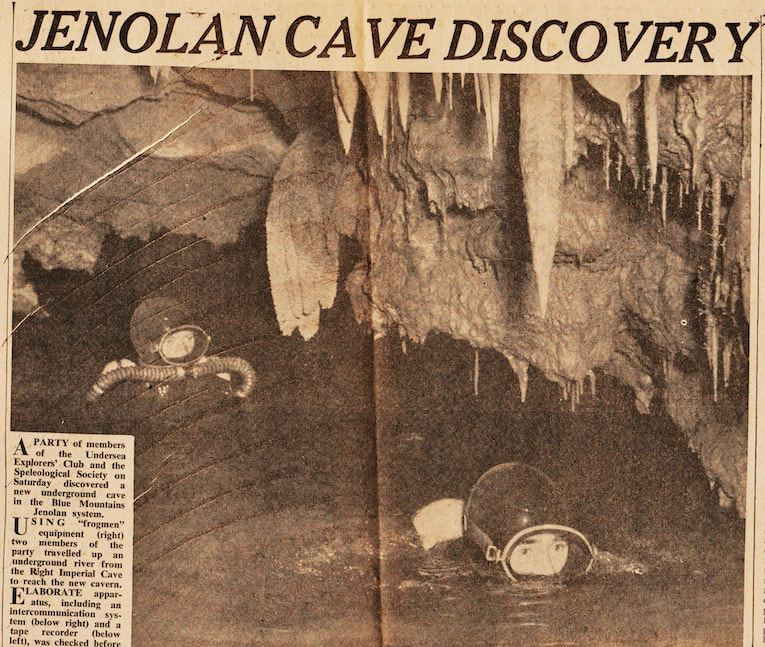

From bushwalker to climber, but also canyoner and speleologist, Dave was an early participant in the dark arts of diving through sumps in caves using primitive scuba gear. Situated in a deep dale about 175 kilometres by road west of Sydney, the Jenolan Caves are an outstanding tourist attraction. But there were still passages to be found and explored beyond the caves that were open to the public.

For decades cavers at Jenolan dreamed about what wonders were to be discovered in the 1.3km distance between where the Jenolan River disappeared downstream in Lower River, Mammoth Cave, and Imperial Cave where the river re-emerged into the [public] show caves. At this time there were no caves in between that connected the underground river." Earlier groups had started this process in 1952 by undertaking the first cave diving in Australia to find this elusive connection. They plumbed the watery chambers with magnificently primitive equipment initially using a hand bellows to pump air to a face mask via a hose. Dave spent two weekends in October 1954 with climbing compatriots, Russel Kippax, Les Tattersal, and many others to push through the offending sump. Suffice to say there were many adventures of people getting stuck, lights going out, muddy water, cold water, and torn suits. The sump into the new cavern was 36 metres (118 feet) long and amazingly, it was later free dived by Dave. On these trips the hand bellows and airline-hose-to-the-face mask of the earlier dives had been thankfully superseded by the acquisition of more modern aqualungs (scuba gear).

|

Click on above photos to enlarge and read caption.

"Crocks on the Rocks"

In later years, Dave joined a group of older climbers calling themselves the "Crocs on the Rocks." These seasoned climbers set up a civilised camp, sat around the fire yarning and drinking tea, then went climbing. Afterwards the tea was often displaced by a glass or two of red, and the laughter, joy and repartee continued. I often crossed paths with them, mainly at Mount Arapiles, still living the dream. For Dave that climbing dream, laughter and joy extended for 70 years.

Dave was a pioneer, pathfinder and very popular climber, his infectious grin always going before him. His climbs and his forays onto Balls Pyramid were towering achievements for the time, making him “a truly iconic Australian adventurer and climber." While he will be sadly missed, his climbing legacy lives on in my mind and in those of many others. That legacy is also well etched into our much-loved and fondled sandstone cliffs and crags. But Dave Roots had a further attachment to the rocks by holding a PhD in Geology and being an authority on Blue Mountain landscapes, including the ongoing exploration of the wonderful and much-loved Jenolan Caves. Therefore, I would like to finish with a fond adieu to Dave by quoting the following poem

In later years, Dave joined a group of older climbers calling themselves the "Crocs on the Rocks." These seasoned climbers set up a civilised camp, sat around the fire yarning and drinking tea, then went climbing. Afterwards the tea was often displaced by a glass or two of red, and the laughter, joy and repartee continued. I often crossed paths with them, mainly at Mount Arapiles, still living the dream. For Dave that climbing dream, laughter and joy extended for 70 years.

Dave was a pioneer, pathfinder and very popular climber, his infectious grin always going before him. His climbs and his forays onto Balls Pyramid were towering achievements for the time, making him “a truly iconic Australian adventurer and climber." While he will be sadly missed, his climbing legacy lives on in my mind and in those of many others. That legacy is also well etched into our much-loved and fondled sandstone cliffs and crags. But Dave Roots had a further attachment to the rocks by holding a PhD in Geology and being an authority on Blue Mountain landscapes, including the ongoing exploration of the wonderful and much-loved Jenolan Caves. Therefore, I would like to finish with a fond adieu to Dave by quoting the following poem

I am homesick for the

Mountains –

My heroic {blue hued} hills –

And the longing that is on me

No solace ever stills”

Adapted from a poem by Bliss Carman

Climb on my friend!

My thanks to David's daughter, Philippa Barker, and long term friend, Rick Higgins for the information, photographs, and very generous assistance that they kindly gave to me.

I also extend gratitude to Channel 9 -TCN - Sydney for kindly giving permission to use the Sports Sunday video of Dave climbing his classic climb - The Mantleshelf.

I also extend gratitude to Channel 9 -TCN - Sydney for kindly giving permission to use the Sports Sunday video of Dave climbing his classic climb - The Mantleshelf.