|

It’s difficult for me to return to the time that diabetes almost claimed my life. I have achieved what seems impossible: I am working again; I am in a loving relationship; And I wake up afresh for new adventures.

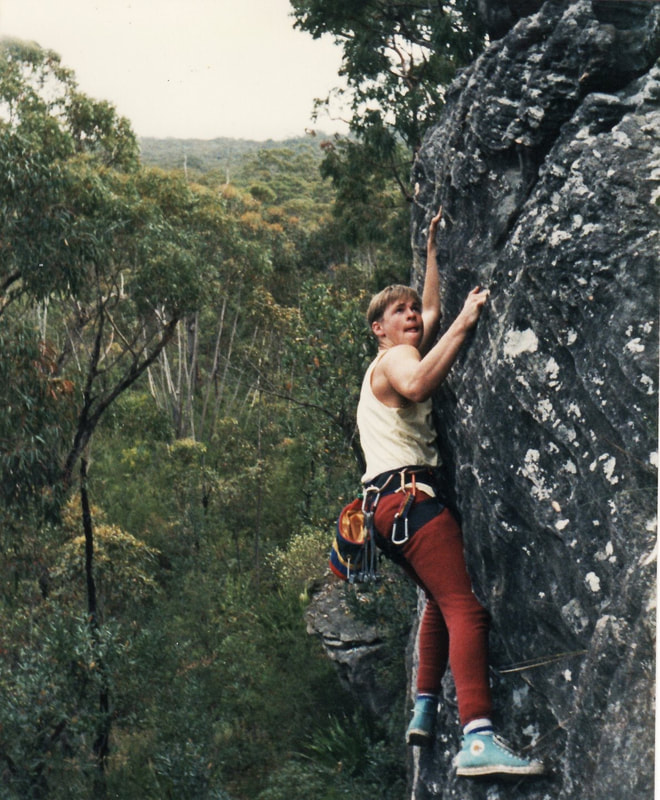

I have always loved adventure. Climbing and I have been buddies since I was young. A wilderness program gave me the opportunity to meet this friend that has both brought heartache and epiphany, love and loss. Climbing was a get-out-of-jail card. Living with a chronic health condition is like walking with a ball and chain around your ankle, you are forced to travel with it. Climbing gave me respite. I think it’s the escape. Up there the challenge is all-consuming and I don’t have to think about "other stuff." When climbing, I am able and alive. There is no ball and chain around my ankle, just lactic acid in my forearms. I just keep holding on. Holding on as a Type 1 diabetic and as a climber hasn’t all been completed free. I’ve had long days cragging and in the evening my blood sugar plummeted. I’ve been rescued from friends' lounge room floors, airlifted by a helicopter in New Zealand, and felt like a dead-man-walking when climbing with high blood sugar caused by adrenaline and dehydration. It feels like a bad flu or when haven’t slept for three days. I’ve learnt to fight my way through. |

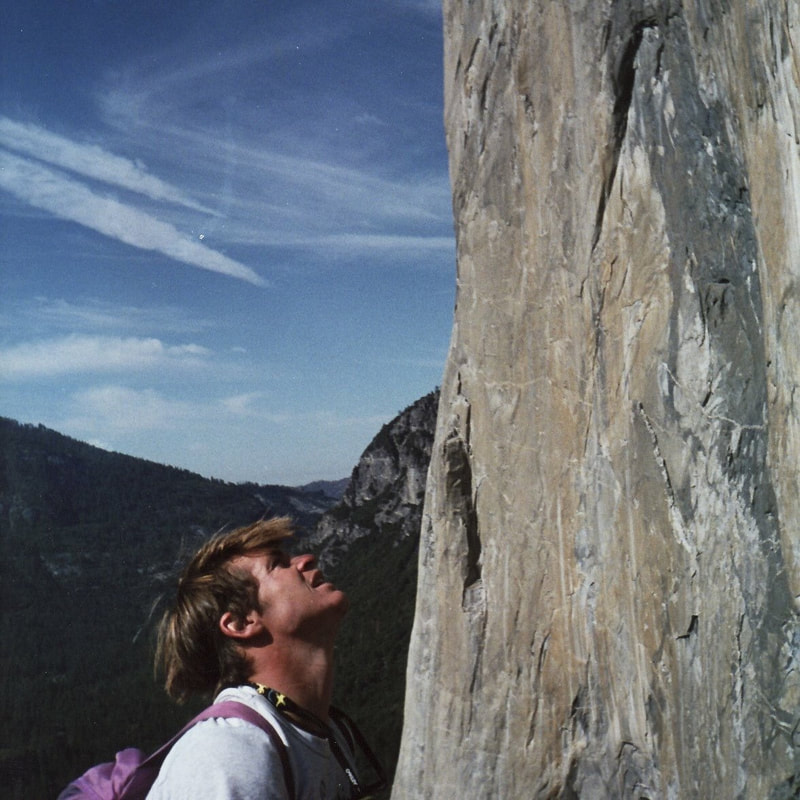

Climbing with diabetes was more difficult when I was a young climber. As I worked to push my grades and climb as frequently as I could, diabetes weighed on me. I carried more weight than my bro’s due to extra insulin and food. These were the days when insulin wasn’t so good and when diabetes technology was non-existent. I pulled as hard as I could to climb 26 (5.12), but my body found the efforts at these higher grades difficult to sustain. I tried anyway and am proud of those achievements. Being a 21-year-old Type 1 on El Captain remains for me one of the most life-giving experiences.

A couple of years ago I was training for an Ironman Triathlon. I had a family and had given up climbing due to life’s other demands. While training I pushed hard, chasing that escape, sticking my middle finger up at diabetes. It caught up with me.

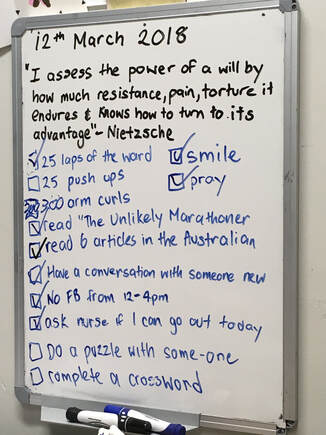

One evening after a ten-hour training day I fell asleep, waking a week later in Hobart hospital. This time catastrophic hypoglycemia left me with a third of my brain destroyed and six months in rehabilitation. I was broken. Every every day since I have been on a search to reclaim what was lost. This included my family and my profession as a social worker. My marriage was another casualty.

One evening after a ten-hour training day I fell asleep, waking a week later in Hobart hospital. This time catastrophic hypoglycemia left me with a third of my brain destroyed and six months in rehabilitation. I was broken. Every every day since I have been on a search to reclaim what was lost. This included my family and my profession as a social worker. My marriage was another casualty.

|

This is where it gets interesting. My brain injury destroyed many of my neurons. Brains are resilient beasts though, as the intact neurons can grow around the damaged ones. I hadn’t climbed for fun for 16 or so years, but as the new neurons connected, they shook hands with my old climbing ones and my passion for the game came back.

The trigger was a piece I wrote about my situation and climbing. Paul Pritchard, who is a climber and writer that sustained brain damage from rockfall while climbing the Totem Pole, came into the rehab ward to give me some encouragement. Not only was it a tremendous boost to be visited by one of my climbing icons but also, he got it. He understood what I was facing. Paul whispered some words to keep my head up and invited me to come climbing when I was released. Paul also introduced me to another climber, Conrad Wansbrough, both of whom have been my rock these last years. I’m so grateful for the mountains and the people they have brought into my life. Not long after that first climb post brain injury, I put up my first route in 16 years, Mr. Bodacious (14). It's nothing grand, a simple sea cliff line, but those who knew the backstory understood its meaning. |

|

Along with climbing, I also began writing. Over time I developed conviction and my scribbles captured the vibe and spirit, rather than the technicalities, of climbing. With those early writings came reunions with my old climbing buddies, as well as connections to new ones, and a hunger to write more. The writing overflowed from my climbing reawakening. I had not really written before, but the climbing life had stored these words inside and my injury released them. I have been fortunate to interview and meet some of the most illustrious climbers of our age, researched and written a novel about climbing on Mars, and remain the Assistant Editor of Common Climber Magazine. Climbing not only rescued me, it now provides a livelihood and purpose. I owe it my life and I love sharing your stories. It’s my pay-it-forward.

I often wonder why my damaged brain reconnected to my climbing roots? Possibly because climbing has always provided a home. It also understands hardship. Or maybe my surviving brain needed some stoke to keep me on route for the next chapter of my life, reconnecting me with those frothy buddies. Now, in hindsight, I know how lucky I am to be alive and have loving people around me. I know I need to be that person in return. I know that climbing and climbers are stories worth sharing as they glimpse the mortal coil more than most and understand the value of truely living. They get me and I get them. We have each others back when the rope is run out, the sky turns dark, and when you are feeling exposed and alone. There’s always someone down there saying, “I’ve got you.” That’s good enough for me and has and will give me the confidence to go on. |

|