Author’s Note: This is a longer version of a story from Hangdog Days: Conflict, Change, and the Race for 5.14 (Mountaineers Books).

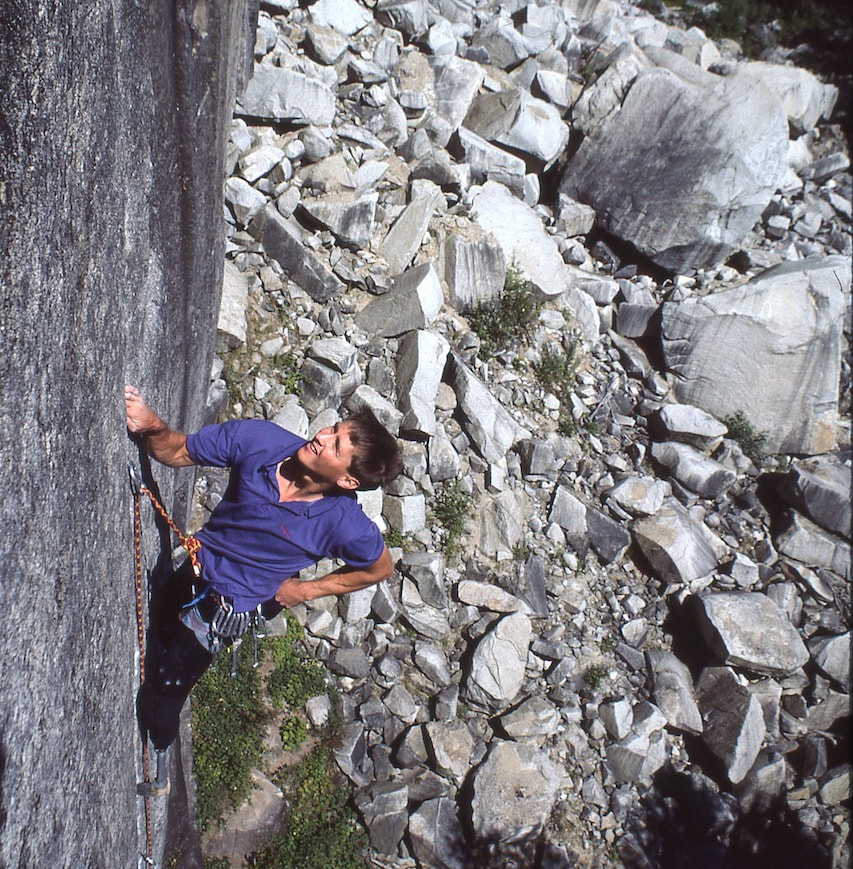

“Let’s go to Yosemite,” Hugh Herr blurted out on the ride back to Seattle. He had just made the second free ascent of City Park, Todd Skinner’s 5.13d test piece at Index Town Walls, and was feeling inspired. “I want to climb The Stigma.”

“Seriously?”

“Yeah!”

“No way!” I said. “They want to kill me. Seriously!”

“Think about it,” Hugh said with that smirk of his. “Todd Skinner climbed The Stigma, then Alan Watts did it. Think how much it would piss them off if an amputee came in and climbed it! Hell, I climbed City Park, and it’s harder than The Stigma, right?”

“That would be something,” I agreed.

“It would. It would. Think about it. It would be awesome!”

Hugh laughed himself silly at the thought of it, but he seemed serious. Even though Hugh was a bilateral amputee—he’d lost both of his legs below the knee to frostbite after an ice-climbing trip gone wrong in 1982—he’d proven on City Park that he could make quick work of The Stigma. They were both steep, vertical pin-scarred cracks rated solid 5.13.

“Let’s go to Yosemite,” Hugh Herr blurted out on the ride back to Seattle. He had just made the second free ascent of City Park, Todd Skinner’s 5.13d test piece at Index Town Walls, and was feeling inspired. “I want to climb The Stigma.”

“Seriously?”

“Yeah!”

“No way!” I said. “They want to kill me. Seriously!”

“Think about it,” Hugh said with that smirk of his. “Todd Skinner climbed The Stigma, then Alan Watts did it. Think how much it would piss them off if an amputee came in and climbed it! Hell, I climbed City Park, and it’s harder than The Stigma, right?”

“That would be something,” I agreed.

“It would. It would. Think about it. It would be awesome!”

Hugh laughed himself silly at the thought of it, but he seemed serious. Even though Hugh was a bilateral amputee—he’d lost both of his legs below the knee to frostbite after an ice-climbing trip gone wrong in 1982—he’d proven on City Park that he could make quick work of The Stigma. They were both steep, vertical pin-scarred cracks rated solid 5.13.

Todd Skinner had made the first free ascent of both routes, but not without a lot of hangdogging. On The Stigma, a thin pin-scarred crack on the Cookie Cliff in Yosemite, Todd had pre-placed pitons for protection. Both ascents had taken Todd thirteen days of effort, and both ascents had generated heated controversy. Alan Watts had repeated The Stigma in only a handful of attempts, and in better style, but he’d still gotten crap about it. The Yosemite locals had been riled up after Todd had proclaimed it possibly the first 5.14 in Yosemite, and they were still riled up three months later when Alan repeated it. Rumor was somebody had pinned out the crack some more after Todd’s ascent to ensure that if it was 5.14, it wouldn’t remain so for long.

After Alan’s ascent — after which he downgraded the route from 5.13+ to 5.13b — all they did was write some crude graffiti in the dust on Alan’s truck window and give him a hard time. Still, it made me mad, and I responded by writing an editorial titled “The Valley Syndrome” that was published in Climbing, in which I called Yosemite climbers to task for being so complacent about pushing hard free climbing, for being stuck in their tired old ways when the sport was clearly changing, and for being such jerks about Todd and Alan. It wasn’t as if they had come into Yosemite and started rappel bolting or chiseling holds on the Cookie Cliff. They had just hangdogged on an old aid crack and worked it out free. What, I wondered, was the big deal?

|

I knew Hugh was right—it would be hilarious to sneak into the Valley and have him fire off The Stigma. He could do it, too, because he could jam his adaptive foot—a hatchet-shaped acetyl wedge wrapped in rubber, that fit nicely into thin, vertical cracks—where Todd and Alan had only been able to smear or edge or layback on the steep, slick granite. Even if he didn’t on-sight it, Hugh could be done with it in an hour or two, and we could be on our way before anybody realized we had been there. Hugh and I laughed about it during the drive home and that night and the next day. We made up elaborate plans to sneak into Yosemite without being spotted. Hugh could ratchet down his prosthetic legs so he appeared to be very short and evade notice. I could wear a disguise, maybe bleach my hair, feign an English accent, and say I was Jerry Moffatt’s cousin, Geoffrey. Maybe if The Stigma went off without a hitch, Hugh could try to free-climb the Nose, too. Why not? If he could adapt his prosthetic feet to free-climb a 5.13d pin-scarred crack, why not give El Cap a try? I gave Hugh’s idea more thought, but the more I thought about it, the worse it seemed. It would be the ultimate insult — an amputee climbing The Stigma in perfect style, belayed by that asshole, Jeff Smoot. This time, I imagined, they wouldn’t just write graffiti on the dusty windows. They would break windows. They would slash tires. They would light my car on fire and trundle it off the nearest cliff. There might even be physical violence.They wouldn’t hit Hugh; he was, as he often proclaimed, a cripple. No, they would hit me. I was at that moment the least popular figure on the Yosemite climbing scene. They hated my guts. Although it seemed hilarious, I kept thinking that somebody in the Valley was so completely outraged about “The Valley Syndrome” that they would go apoplectic, beat the shit out of me, and hang my mangled corpse off the Cookie Cliff. |

It would be confrontational, to say the least, to go back to Yosemite with that wound still so raw with the intention of ripping it wide open again. There would be blood.

I had written the article in anger, though, and my anger had since dissipated. I understood where the Valley climbers were coming from. They were defending the ideal of pure free climbing from the rising horde of so-called tricksters—the hangdoggers and sport-climbers who were starting to invade even the holiest of traditional climbing shrines.

The Yosemite climbers were like a murder of crows, squawking and dive bombing a cat stalking a fledgling that had fallen from the nest, so loud and annoying that one might run outside yelling and waiving one’s arms to drive them off even though they were the aggrieved party. That was me, the ranting idiot yelling with arms flailing. I’d said that Yosemite climbers’ attitudes were self-limiting and suppressing the natural advancement of the sport, the progression from ascendancy to gymnastics. And I’d said that they, the Yosemite elite, were the problem; that they were why American climbers were falling behind the rest of the climbing world.

To be fair, I wasn’t the first person who said it, and I would not be the last, but I was the current person saying it, and I was saying it loud, so the empathetic part of me could understand why they were upset. I had blamed them, shamed them, and rubbed their noses in it in a very public way. Their response was not unexpected. They didn’t like it, but mostly they didn’t like me. Fair enough; I deserved it. I had said what I felt I had to say, which was meant to get the reaction it got. I had written from emotion, and received an emotional response. But to return to the Valley at the height of this emotion, with Hugh Herr, an amputee, so he could climb The Stigma and further fan the flames, would be too much. I would be digging my own grave.

After I explained all of this to Hugh, he agreed it would be bad form for me to show up in the Valley right then, or for him to go anywhere near The Stigma.

I had written the article in anger, though, and my anger had since dissipated. I understood where the Valley climbers were coming from. They were defending the ideal of pure free climbing from the rising horde of so-called tricksters—the hangdoggers and sport-climbers who were starting to invade even the holiest of traditional climbing shrines.

The Yosemite climbers were like a murder of crows, squawking and dive bombing a cat stalking a fledgling that had fallen from the nest, so loud and annoying that one might run outside yelling and waiving one’s arms to drive them off even though they were the aggrieved party. That was me, the ranting idiot yelling with arms flailing. I’d said that Yosemite climbers’ attitudes were self-limiting and suppressing the natural advancement of the sport, the progression from ascendancy to gymnastics. And I’d said that they, the Yosemite elite, were the problem; that they were why American climbers were falling behind the rest of the climbing world.

To be fair, I wasn’t the first person who said it, and I would not be the last, but I was the current person saying it, and I was saying it loud, so the empathetic part of me could understand why they were upset. I had blamed them, shamed them, and rubbed their noses in it in a very public way. Their response was not unexpected. They didn’t like it, but mostly they didn’t like me. Fair enough; I deserved it. I had said what I felt I had to say, which was meant to get the reaction it got. I had written from emotion, and received an emotional response. But to return to the Valley at the height of this emotion, with Hugh Herr, an amputee, so he could climb The Stigma and further fan the flames, would be too much. I would be digging my own grave.

After I explained all of this to Hugh, he agreed it would be bad form for me to show up in the Valley right then, or for him to go anywhere near The Stigma.

|

So, where to go?

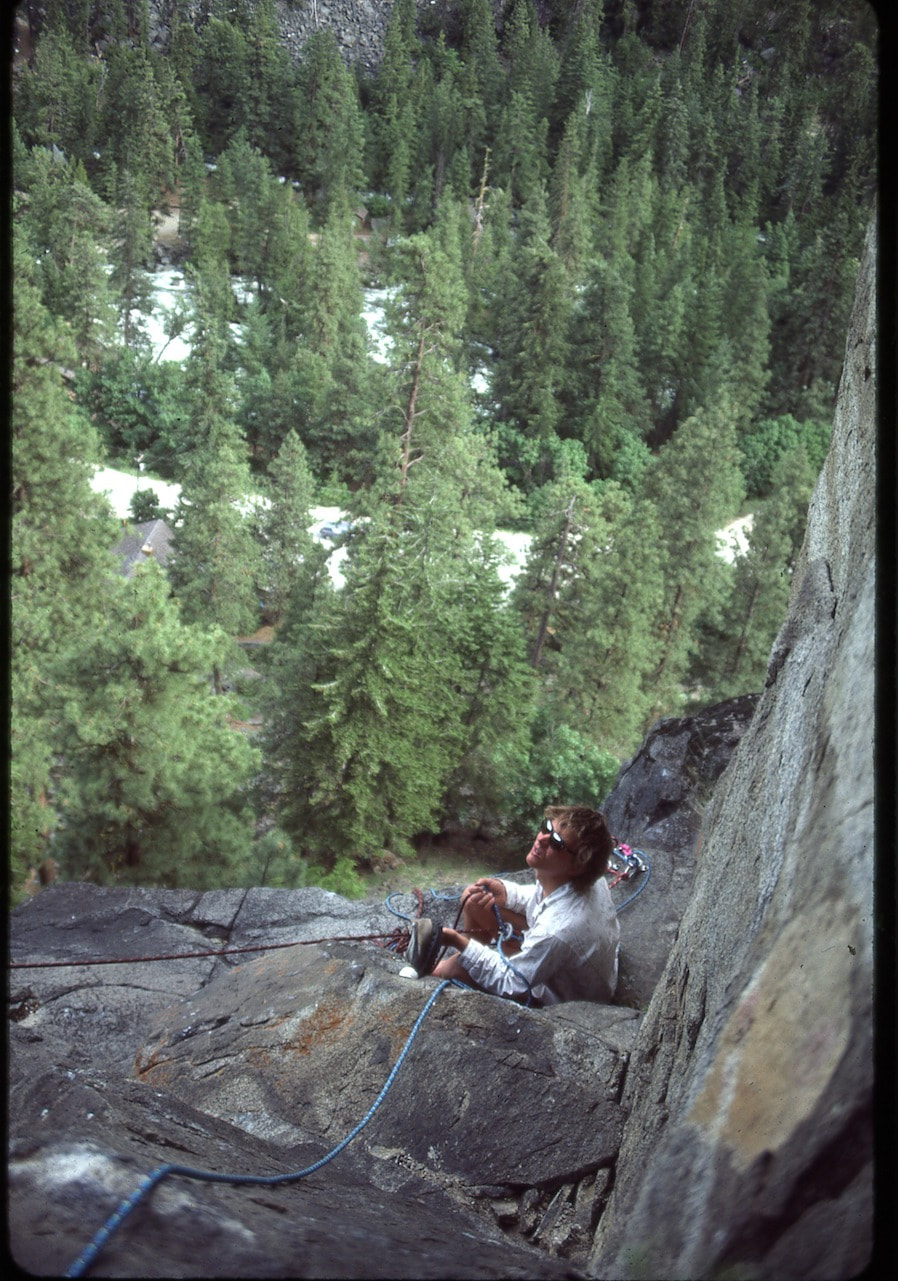

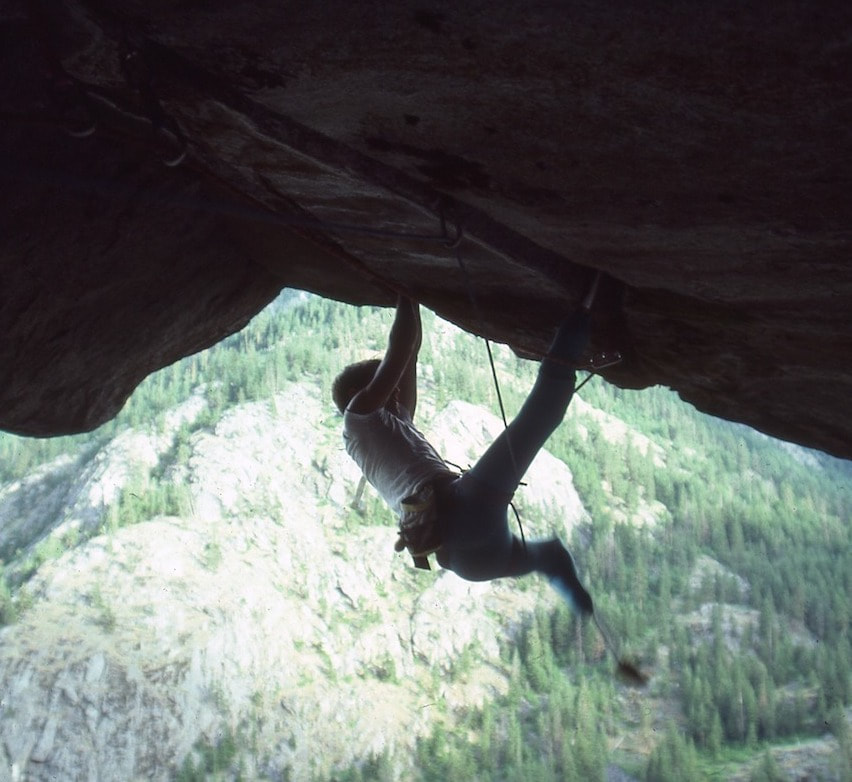

There must be some other hard crack somewhere in America that would satisfy Hugh’s ambition. Hugh wanted an unclimbed roof crack, something impossibly hard for mere mortals that he could climb by virtue of his superior strength, mechanical aptitude, and nonpareil strength-to-weight ratio. Fortunately, I knew just the crack, and we didn’t have to drive to Yosemite to find it. Two days later, Hugh and I, accompanied by Russ Erickson, our local dirtbag savant who had appeared on the scene out of nowhere as usual, were hiking a dusty trail up a boulder-strewn slope a few miles outside of Leavenworth, Washington, for a try at Early Morning Overhang, a 25-foot roof crack that stuck out conspicuously above Icicle Creek Road. A popular aid climb, it was considered “impossible” to free climb because it was so overhanging and so thin in places it didn’t seem feasible to climb it without aid. It was the only local roof crack I could think of that had not been free-climbed already that might measure up to Hugh’s exacting specifications. We scrambled up a short pitch to a ledge below the roof, and Hugh set to work. He attached his hatchet feet and racked up pensively, squinting up at the two parallel cracks splitting the roof, wondering if it was worth his while. Russ belayed me up the steep slab that led to the base of the roof, where I plugged in some cams and hung out to take pictures. Hugh led up behind me on double ropes, belayed by Russ. After a short rest, he started jamming out the cracks. |

The cracks varied from fingertips to off-hand, and were perfectly horizontal, kind of like Separate Reality in Yosemite only longer and more irregular.

Hugh took a couple tries figuring out the initial thin moves, then powered to the lip like any able-bodied climber would, suspended horizontally, hands and feet jammed in the cracks, body hanging below. Although the finger and hand jams were overhanging and rough, Hugh powered through the moves. As for his feet, he was able to poke the hatchet-shaped wedges into the cracks and torque them, which gave him enough leverage to hang on, although he couldn’t hang his full weight on his prosthetic legs without them pulling loose. He wore lycra tights when climbing; the stretch of the fabric held the socket firmly in place, which worked fine on vertical and slightly overhanging walls, but not as well on horizontal overhangs. Because he was upside down, if he put too much weight on his feet it would, in theory, pull his prosthetic legs right off.

Sure enough, the first time he got to the lip of the overhang, it happened.

Hugh took a couple tries figuring out the initial thin moves, then powered to the lip like any able-bodied climber would, suspended horizontally, hands and feet jammed in the cracks, body hanging below. Although the finger and hand jams were overhanging and rough, Hugh powered through the moves. As for his feet, he was able to poke the hatchet-shaped wedges into the cracks and torque them, which gave him enough leverage to hang on, although he couldn’t hang his full weight on his prosthetic legs without them pulling loose. He wore lycra tights when climbing; the stretch of the fabric held the socket firmly in place, which worked fine on vertical and slightly overhanging walls, but not as well on horizontal overhangs. Because he was upside down, if he put too much weight on his feet it would, in theory, pull his prosthetic legs right off.

Sure enough, the first time he got to the lip of the overhang, it happened.

“Damn it!” Hugh said, “my foot’s stuck.”

Hugh was trying to make the last move to get in position to turn the lip when his right foot became wedged in the crack. It was catching on something and wouldn’t come out no matter which way Hugh turned or pulled it. He struggled for a minute, trying to wiggle it loose. It finally did come loose, but not the way he intended. It didn’t come out of the crack; instead, the socket slipped off his residual leg, leaving the foot still stuck in the crack.

“My leg is falling off!” Hugh screeched.

Unable to do anything with a detached prosthetic leg, Hugh let go and fell. Luckily, his leg fell with him. Although it had detached from the stump, it was held by his lycra tights and was pulled out of the crack as Hugh fell. Now it, and Hugh, dangled impotently in the air.

“Well, that’s a first,” Hugh said, pulling his leg back into place. “I’ll have to tape it on better next time.”

While Hugh rested and taped his legs on better, Russ and I each gave the roof a try. I went first, and made it out a couple of moves before I was pumped beyond recognition. This presented a problem, since Hugh’s gear was way out near the lip. Having neglected to set a back rope, falling off meant a big swing into space. At first, I didn’t want to let go, so I tried to reverse the moves, with the predictable result. Knowing I was about to fall, I took a deep breath and released. Woooooosh! I swung wildly down and out into space a hundred feet off the ground, then careened back toward the wall. To my relief, I didn’t hit anything. Actually, it was fun, so much so that I climbed back up to the base of the roof and did it again, and again.

Russ made a half-assed attempt to climb the crack, then he, too, resorted to swinging, sometimes hanging upside down with his arms and legs spread wide, laughing the whole way.

Hugh wasn’t interested in our fooling around. He had business to attend to.

Once Russ and I were done swinging — and after he’d taped his prosthetic legs to death so there was no way they’d come loose ever, ever again — Hugh was back on the roof. He grunted out the cracks like before. The tape job worked; his foot didn’t get stuck and his legs stayed firmly in place. He reached the lip, turned it, and muscled his way up the vertical wall above, his prosthetic legs dangling in space, disappearing little by little until he was out of sight. The ropes kept moving as he climbed the last few feet up to a ledge above the roof, then it stopped. Someone watching from the road below let out a whoop. Hugh had done it; the “impossible” roof had been climbed free.

"That was good,” Hugh said after aiding back across the roof to retrieve his gear and informing us that he thought the pitch was only 5.12a in difficulty, hard but not hard enough (Ed note: Hugh named the climb "Flight of the Valkyries.")

“What else have you got?”

“Nothing,” I told him. “We’re going to have to leave town to find anything hard.”

I threw out some ideas. “East Face of Monkey Face?”

“It’s a face climb,” Hugh said. “I want to climb a crack.”

“Fallen Arches?”

“Nothing,” I told him. “We’re going to have to leave town to find anything hard.”

I threw out some ideas. “East Face of Monkey Face?”

“It’s a face climb,” Hugh said. “I want to climb a crack.”

“Fallen Arches?”

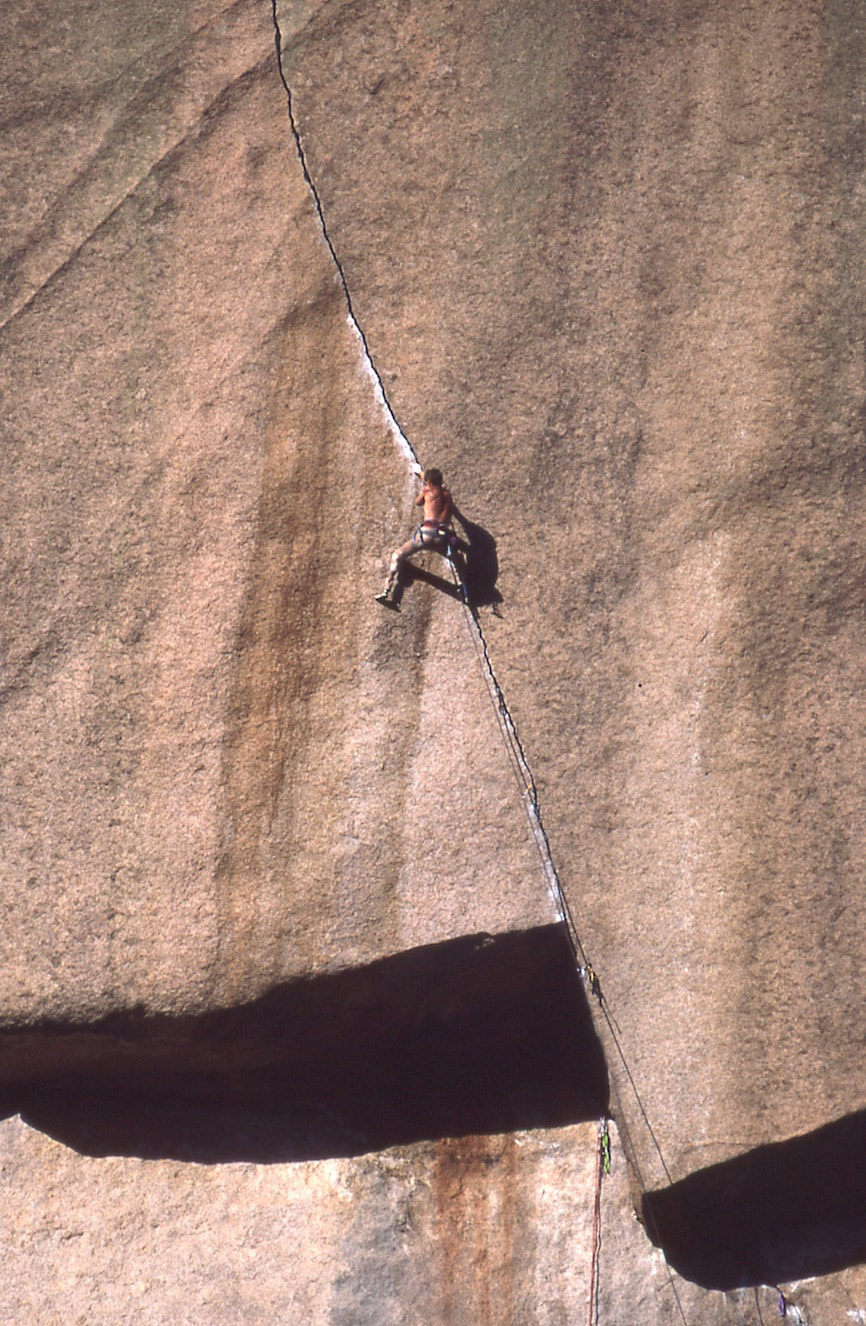

|

“It’s only 13a. And it’s got a bunch of sideways jamming and laybacks.” “Has anybody climbed that roof problem in Little Cottonwood Canyon? What’s it called?” “Yeah. Coffin Roof. It’s 12c or something. I want something hard.” “City Park’s the hardest crack you’re going to find, I think.” “I want to climb something amazing.” “Let’s free El Cap. Hudon and Jones freed all but ninety feet of the Salathé Wall. Maybe The Nose will go free.” “Yeah, right,” Hugh chided me. “You want to go to Yosemite now?” “Never mind. How about Sphinx Crack?” “I don’t know. Maybe.” It went on like that for a while, but time was running short. Hugh had to get back to Boston in a couple of weeks. He had some friends in Boulder he wanted to hang out with before he started classes at MIT. I was running out of money, and had a car payment coming due. I didn’t have the resources to be driving aimlessly all over the country supporting Hugh’s crack habit. I had to get a job eventually. We had to make a decision. After ruminating for many hours over what to do, Hugh finally resigned himself to give Sphinx Crack a try. It was 5.13c. It was worthy. He made a couple of phone calls to let his Boulder friends know he was on his way. The next morning, we were on the road, bound for Colorado. |