|

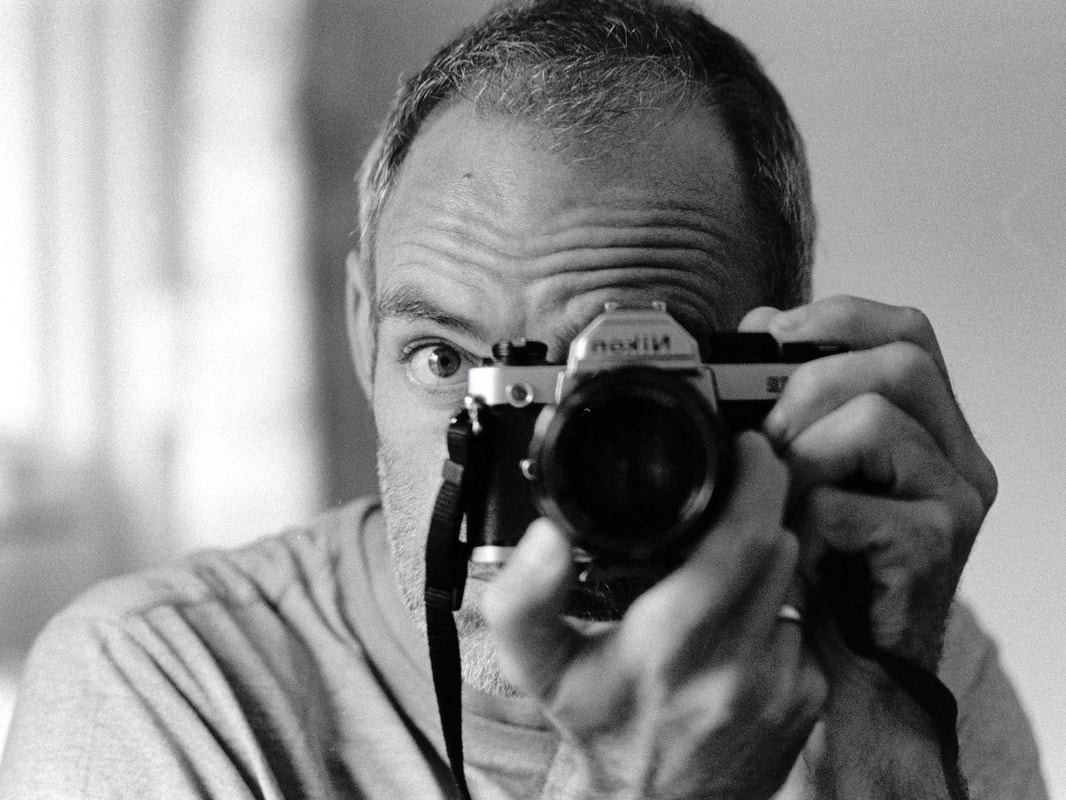

Dave Parry is a photographer, climber, and author. He began his climbing career on the gritstone crags of the Peak District in England, and after a quarter of a century of dedication and hard work is convinced he will get the hang of it any day now. Dave finds breezy spring evenings climbing on Sheffield’s local gritstone crags hard to beat. Dave has written his first climbing book, Grit Blocs, which is being released in September 2022. This is an interview with questions from Common Climber, as well as, a few shared from the publisher Vertebrate Publishing. Thank you Dave for sharing your story with Common Climber readers!

-- Stefani Dawn (Ed.) |

|

Your book description says "100 of the finest must-do boulder problems on the gritstone outcrops, edges and quarries of the Pennines." How did you decide on which boulder problems to include?

The selection of problems is the result of two concepts colliding. Firstly, the notion of what top-quality bouldering should look like to compete with the best in Fontainebleau or beyond : only non-eliminate problems that top out; they shouldn’t have chipped holds or be on poor quality rock; and, any sit starts should be sort of obvious, natural sit starts without excessive rules. Problems at banned venues were also ruled out of contention.

The second concept was the idea of showcasing a broad range of bouldering styles, across the grade range from the very easy right to the unrepeated top-end, highball and lowball, across the full geographic spread of Pennine gritstone. It also includes old classics and new unsung gems, to try and spread the load a little and encourage folks to get off the beaten track. In the end, a few of those rules were bent in places, but never broken. But, even with those guiding principles, it’s an almost impossible task. There is paralysis of choice - everyone has their own opinion on what the best is, and it’s impossible to please everyone. There are also one or two problems I would have liked to include, but deadlines and logistics just made it impossible in the end. But I’m pretty happy with the final selection. The book covers problems from Font 3+ (V0) up to somewhere in the mid 8s (V13/14), across a 140-mile stretch of upland. It gives an authentic picture of gritstone bouldering from a position of genuine affection, and that’s all I can hope for really. |

For those of us that have never climbed on gritstone, describe this rock for us.

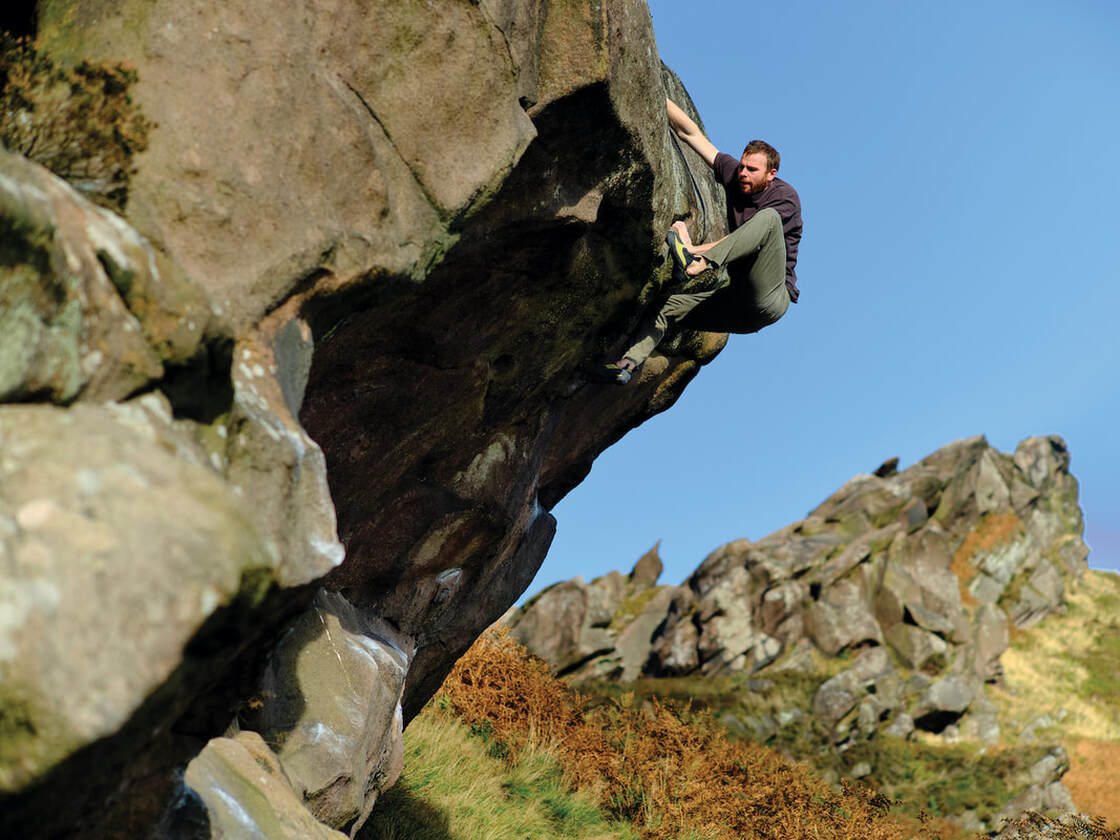

On a geological level, gritstone is sort of hard, coarse-grained sandstone. For the most part it’s quite rough, although there’s a huge variety in grain size of the texture of the surface. Some venues are almost sandstone-like in texture with rounded shapes and very fine grain, others can be full of pockets, and quartz pebbles. Some places have grit so coarse and rough it’s really savage to climb on. With most gritstone being close to the industrial cities of the North of England it’s also been quarried in certain places to provide building materials and grindstones - quarried grit can be very angular, smooth and frictionless, or in some places almost granite-like.

So in terms of climbing it does provide a range of styles, but really it’s famed for infuriatingly technical, not too steep, slopey friction-dependent - and sometimes bold - climbing. When people usually think about grit they’re basically imagining technical walls, bulges, slabs, tall aretes, slopers, airy topouts, and having the skin on your fingertips totally destroyed by the end of the day. Grit can be quite a punisher, so you’re either going home with your head in your hands or having had the best day of your life. On balance, the latter usually outnumber the former.

So in terms of climbing it does provide a range of styles, but really it’s famed for infuriatingly technical, not too steep, slopey friction-dependent - and sometimes bold - climbing. When people usually think about grit they’re basically imagining technical walls, bulges, slabs, tall aretes, slopers, airy topouts, and having the skin on your fingertips totally destroyed by the end of the day. Grit can be quite a punisher, so you’re either going home with your head in your hands or having had the best day of your life. On balance, the latter usually outnumber the former.

|

Many of our readers live outside of the U.K. What does a day-in-the-life of bouldering in the Pennines look like? Do you climb in the rain or after it rains? Is moss and slickness a problem or part of the "character"?

Because the weather in the UK is often challenging to say the least (some of us would be less charitable - it’s “crap”) we spend a lot of time weather-watching, training indoors, and planning the next session. Choice of venue on any given day is critical; while you can be enjoying a crisp breezy cool session with good friction, someone else half-a-mile away could be sweating like a pig at a damp humid crag while being eaten alive by biting insects. So, you have to do your homework!

Dry gritstone on a breezy day can shrug off the odd passing shower, but other than a few isolated steep problems (at the base of larger crags) you can’t really climb in the rain. Luckily there’s plenty of good indoor gyms in the towns around the Pennines. We also have steep limestone crags which will stay dry in heavy rain which provide some harder bouldering and bolted sport routes, although it has to be said Pennine limestone is an acquired taste, and during the winter most of it is wet from groundwater seepage anyway. In sunny and breezy conditions, many gritstone crags can dry very quickly after rain, but unfortunately this is sometimes a double edged sword. Many climbers insist on heading out and trying to climb before things have completely dried, hence destroying the rock and ruining problems. I could take you to problems which are unrecognisable compared to 10 or 15 years ago. This behaviour seems to be increasingly prevalent, and at times it feels like the desire for a “tick” and to share success on social media at all costs might be pushing people to make poor choices. This is something as a community we need to raise our game on. |

Why did you decide to feature 100 problems and opt for this style of book?

First and foremost the book was inspired by Stephan Denys’s Bleau Blocs book, which was published in France in 2020, and Vertebrate published an English translation of the book here in the UK in 2021. Like Grit Blocs, it showcases 100 of the finest problems across the grade spread, so that really set the template both thematically and in terms of the overall look and feel as the graphic design is essentially in the same style.

Beyond that, in the gritstone-world, we sort of live in the shadow of Fontainebleau bouldering - we use their grading scale and the best compliment anyone can give a problem here is to say it’s “Font-like." Really the book is a way of seeing how we match up against Fontainebleau, and celebrating what we’ve got that’s special or in some way unique. I think this is especially important these days, with increasing numbers of people getting into climbing, because if we don’t celebrate what’s special then it’s hard to make a case for preserving it - being good custodians of our crags and looking after the rock.

Also, in British climbing we have a long tradition of this sort of coffee-table climbing book. Traditional climbing has always been well-catered for with the iconic and influential Hard Rock series, started by Ken Wilson in 1974, along with all the other flavours of book in the same mould - Classic Rock, Extreme Rock, Cold Climbs, etc. These books have inspired generations to get out there and experience the full range of British climbing. Back when these books were first published, bouldering wasn’t really taken seriously as a pursuit in its own right by many, but with bouldering having come of age over the last couple of decades it’s a privilege to now be able to add to this tradition and make sure grit bouldering is suitably represented.

Beyond that, in the gritstone-world, we sort of live in the shadow of Fontainebleau bouldering - we use their grading scale and the best compliment anyone can give a problem here is to say it’s “Font-like." Really the book is a way of seeing how we match up against Fontainebleau, and celebrating what we’ve got that’s special or in some way unique. I think this is especially important these days, with increasing numbers of people getting into climbing, because if we don’t celebrate what’s special then it’s hard to make a case for preserving it - being good custodians of our crags and looking after the rock.

Also, in British climbing we have a long tradition of this sort of coffee-table climbing book. Traditional climbing has always been well-catered for with the iconic and influential Hard Rock series, started by Ken Wilson in 1974, along with all the other flavours of book in the same mould - Classic Rock, Extreme Rock, Cold Climbs, etc. These books have inspired generations to get out there and experience the full range of British climbing. Back when these books were first published, bouldering wasn’t really taken seriously as a pursuit in its own right by many, but with bouldering having come of age over the last couple of decades it’s a privilege to now be able to add to this tradition and make sure grit bouldering is suitably represented.

What was it that made you decide to write a book and what was the process like for you? What were some of the rewards and challenges?

As a photographer and climber there’s certain opportunities you just don’t pass up on. The chance to write Grit Blocs for Vertebrate Publishing was one of those rare instances of the stars aligning. In a way it’s a dream project for me and these things don’t come around too often.

The creative aspects of the book - the shortlisting of problems to include, the writing and the actual photography - were one set of challenges that came about as expected. All the usual nagging self-doubt and existential dread that most writers get at some point. But there was another set of hidden challenges I maybe wasn’t expecting, which were a sort of complex interplay of logistical factors to be juggled when trying to go out and shoot new images for the book.

For instance, some of the crags are several hours drive from where I live - so I’ve got to get there, to climb or at least check out some problems I might not be familiar with, and also have a climber I can photograph who’s capable of climbing whatever the problem is and is willing to put the time aside to do so. Some problems aren’t just the sort of thing you can ask someone to casually throw a lap on - there’s stuff in the book which is bold, high, hard, or all three! In a few cases the problems might have only ever been climbed once. On top of that, the weather has to be dry and the conditions right for climbing the problem. The deadlines don't always allow the time to wait for the perfect lighting or the perfect weather and doing 100 separate road trips isn't really feasible.

It was an absolute pleasure to be able to tour around the various crags of the Pennines under the guise of “work” though. I really got to see some places I already knew in a fresh way, and experience a whole load of new venues and new climbing. I added a few more problems to my personal ever-growing to-do list. It pushed me outside my normal comfort zone in many ways. I have grown as a writer, photographer, and a climber as a result. Not least, I was lucky enough to be able to work with some amazing climbers who were incredibly psyched and supportive. Some people who I didn’t really know beforehand but were psyched to jump in the car for the day and climb problems repeatedly for the camera for no other reason than being psyched about climbing, grit, and bouldering. Nobody stood me up, nobody complained, everyone was amazing, and that’s really humbling.

The creative aspects of the book - the shortlisting of problems to include, the writing and the actual photography - were one set of challenges that came about as expected. All the usual nagging self-doubt and existential dread that most writers get at some point. But there was another set of hidden challenges I maybe wasn’t expecting, which were a sort of complex interplay of logistical factors to be juggled when trying to go out and shoot new images for the book.

For instance, some of the crags are several hours drive from where I live - so I’ve got to get there, to climb or at least check out some problems I might not be familiar with, and also have a climber I can photograph who’s capable of climbing whatever the problem is and is willing to put the time aside to do so. Some problems aren’t just the sort of thing you can ask someone to casually throw a lap on - there’s stuff in the book which is bold, high, hard, or all three! In a few cases the problems might have only ever been climbed once. On top of that, the weather has to be dry and the conditions right for climbing the problem. The deadlines don't always allow the time to wait for the perfect lighting or the perfect weather and doing 100 separate road trips isn't really feasible.

It was an absolute pleasure to be able to tour around the various crags of the Pennines under the guise of “work” though. I really got to see some places I already knew in a fresh way, and experience a whole load of new venues and new climbing. I added a few more problems to my personal ever-growing to-do list. It pushed me outside my normal comfort zone in many ways. I have grown as a writer, photographer, and a climber as a result. Not least, I was lucky enough to be able to work with some amazing climbers who were incredibly psyched and supportive. Some people who I didn’t really know beforehand but were psyched to jump in the car for the day and climb problems repeatedly for the camera for no other reason than being psyched about climbing, grit, and bouldering. Nobody stood me up, nobody complained, everyone was amazing, and that’s really humbling.

|

What is it about climbing/rock that pulls you in when it comes to your photography?

This is a tough one to nail down. I’m definitely drawn more to the aesthetic side of things – the scene, the topography of the venue, the rock, the land, and the lighting – in the same way that a straight landscape photographer might be. Rather than trying to just convey the raw emotion of the climber, of the moment, for example – although I’m not totally blind to this.

As climbers we get to experience some amazing places and sometimes some incredible fleeting moments. Photography is really a sort of party trick of time, to be able to apparently freeze a moment in perpetuity. This in itself has tremendous value from a documentary perspective, but even for the pure aesthete it’s sort of the only way we can experience the world without the relentless tide of time steamrollering over us. You can inspect, you can take a breather and consider what’s there and take it all in. You can’t do this with music – if you freeze a sound in time it’s no longer music. But you can appear to freeze a moment in time in a photo and it still works. Out of context it’s still recognisable, your mind can still make that leap of faith and be tricked into being back there in the moment, even if you were never there in the first place. Also somewhere deep down there’s a creative itch that I need to scratch. Part of it is maybe the satisfaction of composing something pleasing no matter where you are, making sense of a scene, the problem solving aspect, crafting something, the workmanship of it; undeniably I find that aspect hugely rewarding. |

As a climber yourself do you have a favorite anecdote about being out on the rock?

Climbing has an amazing capacity for generating incidents, anecdotes and ridiculous occurrences, so there’s a lot to choose from.

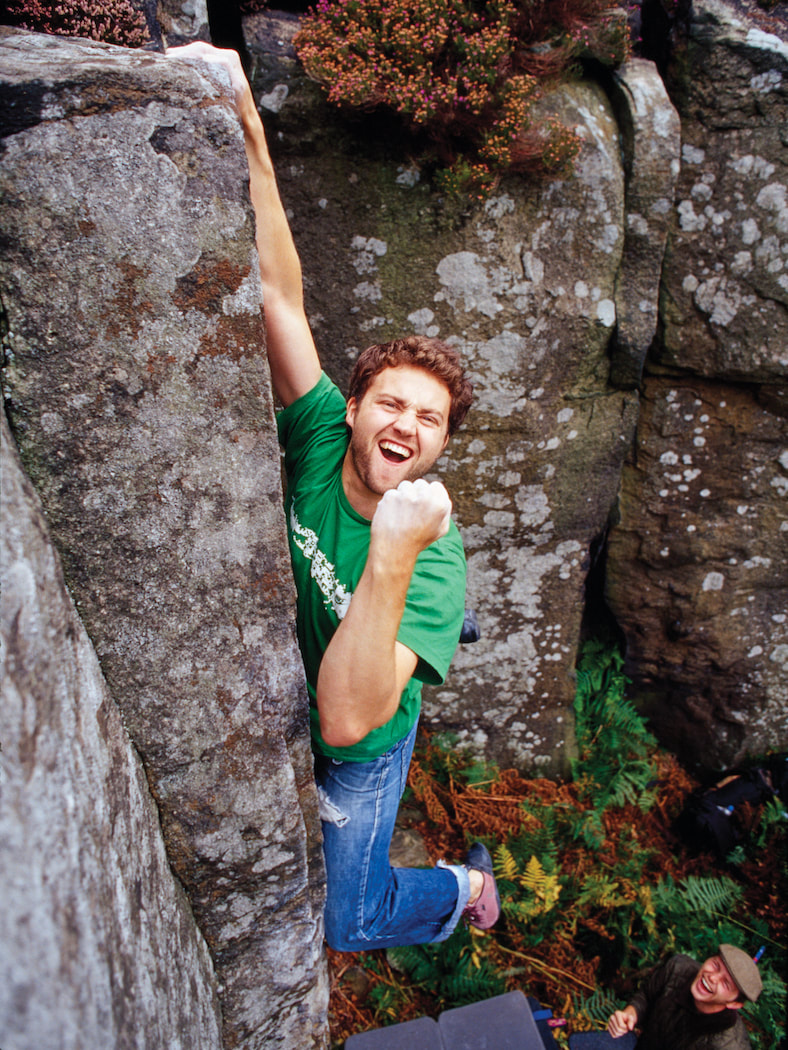

One of my most memorable was on The Joker at Stanage in 2014. This is a classic Jerry Moffatt problem that I’d tried once or twice previously but never with any consistency because it was too hard for me.

On this December day it was great overcast winter conditions. We went up for a look at it, and I surprised myself by doing it with the footless method in half a dozen attempts. I was made up, and on paper it was already my best day bouldering ever.

Admittedly this sounds like the worst look-at-me answer possible but that’s not really why it was that notable; the bizarre thing was by pure coincidence I was trying it on the same day as visiting German wunderkind Alex Megos. One of the best young climbers in the world, he’d already onsighted 9a (5.14d, 34) the previous year aged nineteen. Anyway, despite trying it all afternoon he wasn’t getting anywhere. We hung around to watch him and offer useful beta (as if he needed it?).

For something to do I started trying the left-hand-first original sequence, like Jerry on Hard Grit, and after lots of attempts to my complete surprise I held the top and that was that. Twice in one session, via completely different sequences; meanwhile the world’s best came away empty handed, probably wondering if this entire situation was some kind of elaborate wind-up.

And this is what I love about climbing, and grit in particular; it can still be random and non-linear. It can still surprise you. So on any given day any normal father-of-two having a good day could get up a problem that the best in the world might not manage. If the stars align, it can happen. I don’t know if there’s many other activities or sports where this is the case, and climbing’s all the better for it.

One of my most memorable was on The Joker at Stanage in 2014. This is a classic Jerry Moffatt problem that I’d tried once or twice previously but never with any consistency because it was too hard for me.

On this December day it was great overcast winter conditions. We went up for a look at it, and I surprised myself by doing it with the footless method in half a dozen attempts. I was made up, and on paper it was already my best day bouldering ever.

Admittedly this sounds like the worst look-at-me answer possible but that’s not really why it was that notable; the bizarre thing was by pure coincidence I was trying it on the same day as visiting German wunderkind Alex Megos. One of the best young climbers in the world, he’d already onsighted 9a (5.14d, 34) the previous year aged nineteen. Anyway, despite trying it all afternoon he wasn’t getting anywhere. We hung around to watch him and offer useful beta (as if he needed it?).

For something to do I started trying the left-hand-first original sequence, like Jerry on Hard Grit, and after lots of attempts to my complete surprise I held the top and that was that. Twice in one session, via completely different sequences; meanwhile the world’s best came away empty handed, probably wondering if this entire situation was some kind of elaborate wind-up.

And this is what I love about climbing, and grit in particular; it can still be random and non-linear. It can still surprise you. So on any given day any normal father-of-two having a good day could get up a problem that the best in the world might not manage. If the stars align, it can happen. I don’t know if there’s many other activities or sports where this is the case, and climbing’s all the better for it.

|

How did you first get into photography and climbing?

Climbing happened first for me, which I sort of got into by accident, when I was in my last couple of years of school before university.

I’d always liked walking and hiking and being outdoors, and at my sixth form college a bunch of us all from different schools who didn’t know each other ended up in the same classes, found we had a similar outlook, and started just going walking in the Peak, then North Wales, then drifting into scrambling. Then someone turns up with a rope, and the next thing you know you’re leaving the Foundry for the first time pumped so badly you can’t operate a car door handle. The rest is history. Photography first came in as a way of documenting these days out with friends – this is all pre-smartphones and indeed pre-digital cameras. It sort of spiraled out of control from there once DSLRs became affordable around 2005. Looking back, I was always exposed to photography (pun intended) as a kid; my dad used to shoot 35mm slides and have the projector out all the time. He and my grandad used to have a makeshift black-and-white bathroom darkroom set up when my dad was a youth. My mum also used to work as an assistant to a local pro, Barry Payling – it was at a slideshow run by Barry, probably in the early 1990s, of his photos of Scotland that I first remember being blown away by landscape photography. So one way or another it’s always been around. |

What's your favorite piece of kit or gadget when it comes to either photography or climbing, and why?

For climbing gear, I still haven’t used all my stash of U.S.-made FiveTen Anasazi velcros, which I put into cryogenic storage before they moved production (and the build quality went to pot) – these are still my all-time favourite climbing shoes for gritstone. It’ll be a sad day when these are gone entirely.

Photography wise you can achieve a hell of a lot with just one prime lens somewhere in the slightly-wide-to-normal range. So for Fuji medium format it’s the 50mm, that’s the sort of Anasazi velcro of the lens world.

Photography wise you can achieve a hell of a lot with just one prime lens somewhere in the slightly-wide-to-normal range. So for Fuji medium format it’s the 50mm, that’s the sort of Anasazi velcro of the lens world.