.The roof of my mouth was like used sandpaper. My tongue was cracked and I tasted blood. That sun, that relentless heat, lit up the cliff like a Sunday BBQ. I was being cooked, slowly.

Climbers often drive to the climb the evening before or the morning of their ascent. They enjoy the sweetness of coffee, the sugar in the sauce, and, between bites, the downloading of beta for projects yet finished. These rituals wake the warrior within, feeding the climber for the cruxes ahead. Sugar sweetens the promise of the day and stokes the ego.

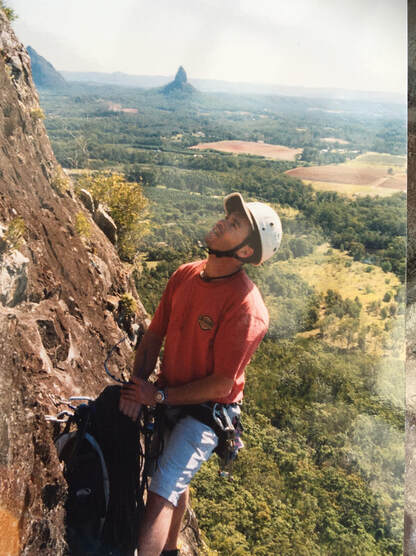

Stepping out of the car, I found myself at Mount Tibrogargan in Southern Queensland, Australia. The Glass House Mountains are what is left of an ancient volcano. From the sea, Captain Cook thought these striking rocky outposts looked like wine glasses, hence the name This cliff had seen a few million hot days in its time; It cared little for mine. I was just another lizard seeking water on a dry summers day. There was no wine to swill around out here.

Climbers often drive to the climb the evening before or the morning of their ascent. They enjoy the sweetness of coffee, the sugar in the sauce, and, between bites, the downloading of beta for projects yet finished. These rituals wake the warrior within, feeding the climber for the cruxes ahead. Sugar sweetens the promise of the day and stokes the ego.

Stepping out of the car, I found myself at Mount Tibrogargan in Southern Queensland, Australia. The Glass House Mountains are what is left of an ancient volcano. From the sea, Captain Cook thought these striking rocky outposts looked like wine glasses, hence the name This cliff had seen a few million hot days in its time; It cared little for mine. I was just another lizard seeking water on a dry summers day. There was no wine to swill around out here.

Climbing in Queensland is a bit like going to a water park, you expect to get wet. Stepping out of our truck sweat immediately came to my brow, it’s salt drip fed into my mouth. Donning our packs, this sweat multiplied. We scrambled through the lush green undergrowth like Indiana Jones. The forest floor had absorbed summer rains, which cascaded down the dark rock walls above. This made for a mouldy smell so strong I could taste it. It smelt like death, but in your throat. Dead things have a way of doing that.

A climb is a climb, but place and position flavour your memory. Here at this place the black rhyolite was crusty and rough like an old persons skin. We started up Sunburnt Buttress (5.10). Recent rains left the rock damp and every move required some gardening to scratch or blow the dirt and/or lichen out. With that travelled a flurry of dirt and moss and who knows what into my nose and mouth. I was no worm. My tongue was not familiar to these unsavoury flavours. It tasted foreign, like a Bear Grylls meal to one of his guests.

At the end of each pitch we would holster the rope over our feet and nibble on dried fruit. I liked dried fruit. It was soft but had a sweetness to it that countered the taste of dirt. We swallowed our warm water way too often on this Sunburnt buttress. Water was more precious than protection on this middle grade multi-pitch climb. We had geared for the climb but not for the thirst. There is no better wine than water when you are parched.

As we climbed higher, brother sun had got a bead on us, we were eggs getting fried. With that came the flies. Queensland flies are like a Jurassic version of Southern flies. These little buggers smell you, to them you are a walking feast. They were taste-testing me. It wasn’t long before I was tasting them. The little meat whistles saw my mouth like a kid sees an ice cream van. Nothing would stop them getting in. Every time I called out to my partner, “Take in!” I would also be taking in a fly or two. Flies do taste a little like chicken - fly dinning.

The taste of climbing is also about gear. A taste that always brings memory is rope. The taste of a rope is maybe the most common taste a climber will savour.

“Slack, give me slack!” I would call out to my partner down there somewhere. Slack would come. I would pull up an arms length to clip a piece of protection. Whilst finding its sling come carabiner, I would raise that bite of rope to my mouth and grit my teeth to hold it fast. With that my taste buds were reminded of a thousand of those bites flavoured with sweat, dirt and kermantle. The spice of a climber’s life. When freed from placing protection, my hand could find my bite of rope. I then released the rope from my clenched jaw and my hand would attach it to the QuickDraw.

“Clipped!” I shouted down to my partner hunkered somewhere below the canopy.

The flavour feast is a similar ritual wherever you climb during a summer in Australia.

By time you had negotiated the hotplate of an Australian vertical beach, your mouth tastes the burn of thirst. Sucking blood off broken knuckles is a meal followed by a mouth full of chalk dust and, if you’re lucky, a swig of warm water. Not appetising.

Man cannot live on climbing alone – or the meals of blood, dirt, and chalk. You get hungry. In another time, another place, I had a mentor called Allan Jones. He loved climbing on the slabs up at Tarana, a granite anomaly behind the Blue Mountains in New South Wales. Granite and fingertips were not made for each other. I would be licking the blood off my tips for the meeting. Blood was common to the tongue at Tarana.

There’s always time for a break. Allan had a thing for a gentleman’s lunch.

We underlings would be eating squashed, stale, sandwiches, trying to wash that down with what little water we had. Allan on the other hand would lay out a bandana. Like a magician he started pulling magic out of his pack. The first item he placed on his blue bandana was a tiny breadboard. OK? He had our attention. Allan pulled out a quart of cheese. He then revealed bread to die for from some mountain bakery. Our eyes looked on like marooned mariners. Allan then revealed a can of fish. We instinctively licked our lips. We were like cats. Allan laid the food out and made his lunch. We watched him enjoy it whilst we ate our cardboard sandwiches.

Allan had mercy on us and shared slivers of cheese cut by his pocket knife. We were transfixed by this magic. Then he gave us some bread.

“Common, eat.” He said.

That bread tasted good. Allan broke bread with us, and in doing so, had transformed into our saviour. For a moment all was good in the world. Food does that to hunger.

That ain't all. Now for Allan’s next trick. In the gap between the Googolplex Crag and Deckout Butress, Al’s picnic was finished with a roasting hot cup of Jo and a piece of dark chocolate. We erupted in applause knowing he had enough magic to share around. Al was a climber’s climber from a time past. Blue Ribbon.

“Ready to do some more climbing lads?” Said Alan as he stroked his goatee and licked his lips. Old climbers always seemed to have an ace up their sleeve. When it came to meals he had a royal flush every time. I had a shit hand of stale bread and often climbed on hungry. The taste of food whilst climbing, or its absence, is worth remembering. Learnings.

Is food, equipment and the environment the only flavours climbers taste up there on the precipice?

No.

The final taste is a concoction of the brain alone and none of the five food groups. It is the sweet taste of success - the long awaited first ascent, escaping from a dangerous predicament, or getting off the climb fast enough to get to the toilet. The taste of success leaves a climber wanting more and climbing is a meal that never satisfies.