We were just boys. What, for god’s sake, were we doing attempting to climb a 300-metre vertical cliff straight out of the sea with no experience, paltry gear, and nothing by way of adult guidance. Such is spring, when saplings think the rainforest owes them greatness.

My mother drops Ian Lewis, Rob Craske, Dave Mitchell and me at the roadhead and says she’ll pick us up in a week. What is she thinking? “Will I ever see my son again?”, “I hope they have a nice time”, or maybe “Have I got everything for tonight’s dinner?”

The dry, dusty, eucalypt scent of Tasmanian country roads rises to greet us. Fat banksias prod into the dissembling air that promises great things. We hunker bulging packs onto already sore shoulders and grunt with dull resignation. Then we are figures strung out along a bush track, urgent, serious, wondering.

My mother drops Ian Lewis, Rob Craske, Dave Mitchell and me at the roadhead and says she’ll pick us up in a week. What is she thinking? “Will I ever see my son again?”, “I hope they have a nice time”, or maybe “Have I got everything for tonight’s dinner?”

The dry, dusty, eucalypt scent of Tasmanian country roads rises to greet us. Fat banksias prod into the dissembling air that promises great things. We hunker bulging packs onto already sore shoulders and grunt with dull resignation. Then we are figures strung out along a bush track, urgent, serious, wondering.

The Chasm is Tasmania’s highest dolerite sea cliff. It plunges 300 metres from the top of Cape Pillar straight down into the sea, and there may be another 50 metres of cliff below sea level. Two high walls meet at a chasm which axes into the cape, pounded most days by big seas and occasionally by monstrous storms hurtling in off the Tasman Sea. On rare days the sea is quiet and laps meekly on the dolerite columns, sentinels of Tasmania’s geologically-vibrant Jurassic past.

We sit that night by a small fire at Perdition Ponds, a campsite remarkably sheltered under wind-blasted casuarinas, just 50 metres from a cliff-edge as the long, narrow and steep cape pushes its way out from Tasman Peninsula. An hour or so’s walk from The Chasm at the end of the peninsula, Perdition Ponds is a place to relax, imagine glories unclaimed, swear unceasingly, and fart whenever possible. My old tape player hammers out Son House and J.B.Lenoir and we sip a small part of our supply of cheap port, unwilling to bring a hangover into the next few days.

The morning is warm and clear. Airs waft into the casuarina stand and shift the steam from our billy. We scrape the burnt bits off jaffles and blow on the steaming cheese and baked beans. Black tea and a two-day growth, with little stubble to show given our immaturity. I am 18, Ian 16. It is 1971. No-one has climbed The Chasm and we are damned sure we want to be first.

We sit that night by a small fire at Perdition Ponds, a campsite remarkably sheltered under wind-blasted casuarinas, just 50 metres from a cliff-edge as the long, narrow and steep cape pushes its way out from Tasman Peninsula. An hour or so’s walk from The Chasm at the end of the peninsula, Perdition Ponds is a place to relax, imagine glories unclaimed, swear unceasingly, and fart whenever possible. My old tape player hammers out Son House and J.B.Lenoir and we sip a small part of our supply of cheap port, unwilling to bring a hangover into the next few days.

The morning is warm and clear. Airs waft into the casuarina stand and shift the steam from our billy. We scrape the burnt bits off jaffles and blow on the steaming cheese and baked beans. Black tea and a two-day growth, with little stubble to show given our immaturity. I am 18, Ian 16. It is 1971. No-one has climbed The Chasm and we are damned sure we want to be first.

|

There is a line that goes from the sea to the summit in one narrow, unbroken crack. Instead of the easiest way up, we dream only of the line. The rock looks smooth, and we assume it will require artificial climbing. We have read all we can about Warren Harding and Royal Robbins aid-climbing in Yosemite Valley and think we know how to do it though we haven’t really practised. We think we have geared up appropriately.

We gather what we have and saunter out to the top of The Chasm at the end of the cape. We lie at the summit and look down to the sea. It is a long, long way down. As the day rolls on, Rob and Jeff decide to head back to Perdition Ponds. Before they go I lay out our climbing gear on the ground and take a photo, just like photos I had seen from Yosemite before big aid climbs. We shake hands solemnly and their shadows blend into the bush. |

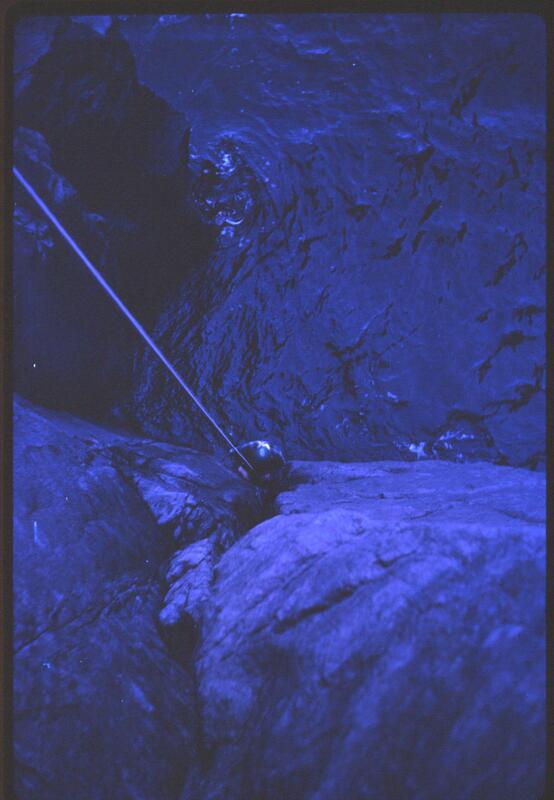

As the day fades, Ian and I scramble down the steep gully east of the Chasm to 30 metres above the sea. We scrape small platforms in the steep dirt, eat an uncooked meal, and lie down to sleep. We begin to feel the enormity of what we have taken on. The cliff spires into the dark. The sea rises and sighs, rises and sighs. Then the lighthouse on Tasman Island begins to rotate through the sky… whoomp…whoomp…whoomp…the long arm of light thunders under limp clouds, drenching the night with wave after wave, warning away the foolhardy, threatening disaster to all who approach. We hardly speak, and hardly sleep, anxiety amplified by the pulse of the unspeakable.

In grey early light we sip water, eat lightly, organise climbing gear on slings about our bodies, and stash extra clothes, food supplies, water and spare gear into my home-made haul-sack. Light green canvas with a haul loop and rucksack straps, double sewn and riveted.

In grey early light we sip water, eat lightly, organise climbing gear on slings about our bodies, and stash extra clothes, food supplies, water and spare gear into my home-made haul-sack. Light green canvas with a haul loop and rucksack straps, double sewn and riveted.

|

We hustle down to the lapping water, on ledges that step down and across to the edge of the deep waters and soaring columns. What else can we do but execute the plan, begin the climb? What other option could there possibly be? Just boys. Bristling with expectations that life is like a fireworks display, we just have to light a fuse and great things will happen. The fuse is lit. What option do we have?

The line starts five metres left of the last ledge, out where the rock spears into the sea. We’d rather not start with a swim so Ian sets up a belay and stands by the pack with rope in hand while I prepare to climb. For us, in 1971, belaying means the rope runs from the climber to one of the belayer’s hands, around the back and to the other hand, both protected by leather gloves. If the climber falls, the belayer grips the rope tightly and the leather gloves taking the burn-inducing friction before the rope comes to a halt. We are using laid nylon ropes, less flexible and more friction-inducing than the soon-to-be-ubiquitous kernmantel. I climb out and up to a narrow ledge, traverse the ledge, then lower myself down to footholds and climb across to small holds the base of our long-dreamed line and set up a belay. It seems a fearful place, whelmed by vast grey walls, the wallowing sea under a dull, grey sky, and the regular bass thump of the low swell into The Chasm’s wine-dark cave. Ian follows clumsily, carrying the heavy sack, and gratefully hands it to me to hang from the belay. The crack is shallow, welded up at the back from salt-erosion. The corner is a little less than 90 degrees, awkward. Ian gears up, adjusts his glasses, and begins the climb. It soon becomes apparent that it could take a long time. We don’t know about the use of a "cow’s tail" to enable the leader to stand higher in the home-made etriers and so place more widely spaced gear. |

We do not have sit-harnesses, just waist-bands made of two-inch nylon tape and tied with a tape knot, and for belaying comfort nylon sit-slings I had sewed at home. For big wall aid climbing, we do not have a lot of gear, especially nuts to fit into wide, shallow cracks.

Ian starts to run out of gear after 10 metres so belays at a small ledge and I prusik up to join him. It is awkward getting past him, but eventually the pack is hauled up and tied to the belay and I begin the slow upward movement above. We are not very far above the sea.

I am working at not being too freaked by the seriousness of what we are doing and where we are. We have no way of contacting the outside world – mobile phones do not exist - and the world we are in is grim and intimidating, and we don’t seem to know what we are doing. Yet we are all too aware of what is happening.

I stop after another 12 metres as my gear runs out. It is a hanging belay because there are no holds. I sit in my sit-sling and call "on belay." Ian dismantles his belay, ties the sack to the end of the main rope and prusiks up, cleaning the paltry line of gear as he comes.

As he reaches me, he looks up at the belay, winces, and says, "That’s a bit light on isn’t it?" It seems pretty solid to me. A good placement of a large nut. Just one nut, taking all my weight, our sack, and Ian’s belaying weight.

What was I thinking?

Eventually we get the sack up, and Ian climbs above me, one carefully placed piece of gear at a time. After another 12 metres he bangs a belay piton in at a point where the corner is again less than 90 degrees.

I prusik up to beneath Ian, and it’s a crowded angle in the cliff. I will not be able to climb past without climbing over him. We agree I will bang a piton into a shallow crack in the wall to get past.

I hammer the peg and half its length goes into the crack before it bottoms out, but it seems solid. I tie it off with a short sling, clip into it and step out to hang on the wall. I do not clip myself to Ian’s belay.

We were just boys.

It is easier now for us to haul up the sack. We haul and I take the weight on my peg. Haul, take the weight. Haul, take the weight. Haul, take the weight…

…then my piton spits out of the wall and I fall. I grab a rope with my left hand and shred flesh down the rope at speed. The sack falls. Ian grabs every rope he can see. I stop falling with a bounce.

“Fuck!” is the best sentence I can assemble.

“Look...” Ian yells down at me, and I turn over and see the sack three metres below me, haul loops ripped off, peeled open like a sardine can, the contents exposed but saved by the plastic bag inside the sack. It has counterbalanced my fall but is likely to upend everything into the sea at any moment.

“Are you all right?”

“I’ve burnt my hand really badly,” and the pain starts to overcome the adrenaline. My palm and fingers look like meat pulp.

“Can you tie on there?”

What happens next is a blur.

Ian starts to run out of gear after 10 metres so belays at a small ledge and I prusik up to join him. It is awkward getting past him, but eventually the pack is hauled up and tied to the belay and I begin the slow upward movement above. We are not very far above the sea.

I am working at not being too freaked by the seriousness of what we are doing and where we are. We have no way of contacting the outside world – mobile phones do not exist - and the world we are in is grim and intimidating, and we don’t seem to know what we are doing. Yet we are all too aware of what is happening.

I stop after another 12 metres as my gear runs out. It is a hanging belay because there are no holds. I sit in my sit-sling and call "on belay." Ian dismantles his belay, ties the sack to the end of the main rope and prusiks up, cleaning the paltry line of gear as he comes.

As he reaches me, he looks up at the belay, winces, and says, "That’s a bit light on isn’t it?" It seems pretty solid to me. A good placement of a large nut. Just one nut, taking all my weight, our sack, and Ian’s belaying weight.

What was I thinking?

Eventually we get the sack up, and Ian climbs above me, one carefully placed piece of gear at a time. After another 12 metres he bangs a belay piton in at a point where the corner is again less than 90 degrees.

I prusik up to beneath Ian, and it’s a crowded angle in the cliff. I will not be able to climb past without climbing over him. We agree I will bang a piton into a shallow crack in the wall to get past.

I hammer the peg and half its length goes into the crack before it bottoms out, but it seems solid. I tie it off with a short sling, clip into it and step out to hang on the wall. I do not clip myself to Ian’s belay.

We were just boys.

It is easier now for us to haul up the sack. We haul and I take the weight on my peg. Haul, take the weight. Haul, take the weight. Haul, take the weight…

…then my piton spits out of the wall and I fall. I grab a rope with my left hand and shred flesh down the rope at speed. The sack falls. Ian grabs every rope he can see. I stop falling with a bounce.

“Fuck!” is the best sentence I can assemble.

“Look...” Ian yells down at me, and I turn over and see the sack three metres below me, haul loops ripped off, peeled open like a sardine can, the contents exposed but saved by the plastic bag inside the sack. It has counterbalanced my fall but is likely to upend everything into the sea at any moment.

“Are you all right?”

“I’ve burnt my hand really badly,” and the pain starts to overcome the adrenaline. My palm and fingers look like meat pulp.

“Can you tie on there?”

What happens next is a blur.

|

Somehow I get some gear in and tie on, gingerly lift the sack up and tie it together with some tape. Ian sorts his belay and abseils to a ledge below us, just above the sea. I lower the sack and then myself to the ledge. Ian ties to a rope and swims to the ledge we had left a few hours before, then hauls the rope in as I swim across with the sack, trying the keep the contents as dry as I can.

The sea sighs and washes at our feet, and we agree, with few words, that what we feel is not frustration at ambitions denied, but a vast wash of relief. Fear’s grey predators had been loosed by the night’s warning lighthouse beams and had loped around the grim grey walls hunting, while the slap of siren waves called, cajoled. But here we are, drying in the sun, alive. I find a triangular bandage in the first aid kit and wrap my hand as the first aid course had showed me. We pack up and slowly haul ourselves up the gully to the summit and the walking track, my wounds throbbing madly. The next day, even in the sheltered campsite, we can tell that the wind has picked up. After a meal and a cuppa, we put on jackets and walk out of the casuarina shelter to find an extraordinary wind howling in from the sea. As we cautiously approach the cliff edge, the wind hurls debris up the cliff and into the air. We throw a dead branch over the edge and it is whipped 50 metres into the air and way behind us by the force of the gale. We toss flat rocks out over the edge and they hover in the torrent of air before slowly sinking away. It would be suicidal to walk to the cliff edge. We crawl and then wriggle the last feet before risking a look over the edge and beyond. We can see The Chasm. Huge waves are crashing into the rock and the spray is reaching two thirds of the way up the 300-metre wall. |

If we had continued climbing, we would have been inside the spray, if not inside the waves.

Sometimes things just work out OK.

Sometimes things just work out OK.

Author Lyle Closs has made many first ascents since The Chasm mini-epic, including Mt. Minto in Antarctica and peaks and cliffs in Greenland. Learn more about Lyle and books he has published.