Juan “Bachi” Bautista Garante arrives on his bike and rings the doorbell to summon me. I come down the steep stairs of my Air B-n-B room rental and fumble with the odd keys and locks. Funny how a small change to something so familiar can throw one off.

Juan is sporting a large red Patagonia backpack containing our essentials for the day. His wavy black hair, short beard, and muscular physique give him a ruggedly handsome look. His eyes, smile, and conversation give away the gentleman that he is.

Juan is sporting a large red Patagonia backpack containing our essentials for the day. His wavy black hair, short beard, and muscular physique give him a ruggedly handsome look. His eyes, smile, and conversation give away the gentleman that he is.

Today Juan is going to show me highlights of Buenos Aires, Argentina – the slick neighborhood of Palermo, the lush downtown parks, and the unique local climbing crag.

When climbing and Argentina are in the same sentence Patagonia likely comes to mind, or perhaps the Andes. Those regions are blessed with abundant, steep rock, and a lifetime of climbing adventure. However, Argentina’s most populated and renowned city of 13 million people (including the greater metropolitan area) is surrounded by nothing but flat country. It requires a good 9+ hours’ to arrive at a wilderness outdoor climbing adventure. But the resourceful climbers of Buenos Aires have created an outdoor climbing crag worth bragging about

Juan is one of several instructors associated with the club that oversees the crag (Centro Andino Buenos Aires - www.caba.org.ar). He is also an experienced rock, alpine, and adventure climber. One of his fingers and several toes show the aftermath of multiple surgeries and partial amputations needed to manage frostbite from an Andean alpine climb gone bad.

Although Juan doesn’t have a complete 5-finger grip, and had to relearn balance and climbing footwork, his climbing is strong, fast, and bold. I had the privilege of climbing with him several times in the Pacific Northwest (where I lived previously and he was obtaining a Master’s degree from Washington State University Vancouver on a Argentenian Fulbright Scholarship). Our climbing group nick-named Juan “the climbing machine” because he would gun ropes up trad 5.11+ lines like they were 5.7s.

I grab a borrowed bike and follow Juan – bumping along on cobblestone roads, turning on plentiful one-way streets, and learning traffic rules, or lack there of. As we pass through intersections, I notice there are no stop signs.

On our way to the crag, a soccer (futbol) game results in roadblocks and a traffic jam. Officers signal for us to turn around, preventing us from accessing a shortcut. As we progress down the detour, Juan confides that he does not like soccer. I laugh out of surprise to hear such sacrilege from a native Argentinean. I wonder if publishing this would compromise any of Juan’s friendships.

The alternative route provides a better feel the large government-run sports facility that houses the crag - CeNARD (Centro Nacional de Alto Rendimiento Deportivo). We ride around the perimeter of a huge, concrete, graffiti-covered wall that extends for miles, then turn on a street that cuts the grounds in half. Behind the walls are a full-size soccer stadium, multiple soccer fields, running tracks, indoor and outdoor pools, and training buildings for just about any sport.

When climbing and Argentina are in the same sentence Patagonia likely comes to mind, or perhaps the Andes. Those regions are blessed with abundant, steep rock, and a lifetime of climbing adventure. However, Argentina’s most populated and renowned city of 13 million people (including the greater metropolitan area) is surrounded by nothing but flat country. It requires a good 9+ hours’ to arrive at a wilderness outdoor climbing adventure. But the resourceful climbers of Buenos Aires have created an outdoor climbing crag worth bragging about

Juan is one of several instructors associated with the club that oversees the crag (Centro Andino Buenos Aires - www.caba.org.ar). He is also an experienced rock, alpine, and adventure climber. One of his fingers and several toes show the aftermath of multiple surgeries and partial amputations needed to manage frostbite from an Andean alpine climb gone bad.

Although Juan doesn’t have a complete 5-finger grip, and had to relearn balance and climbing footwork, his climbing is strong, fast, and bold. I had the privilege of climbing with him several times in the Pacific Northwest (where I lived previously and he was obtaining a Master’s degree from Washington State University Vancouver on a Argentenian Fulbright Scholarship). Our climbing group nick-named Juan “the climbing machine” because he would gun ropes up trad 5.11+ lines like they were 5.7s.

I grab a borrowed bike and follow Juan – bumping along on cobblestone roads, turning on plentiful one-way streets, and learning traffic rules, or lack there of. As we pass through intersections, I notice there are no stop signs.

On our way to the crag, a soccer (futbol) game results in roadblocks and a traffic jam. Officers signal for us to turn around, preventing us from accessing a shortcut. As we progress down the detour, Juan confides that he does not like soccer. I laugh out of surprise to hear such sacrilege from a native Argentinean. I wonder if publishing this would compromise any of Juan’s friendships.

The alternative route provides a better feel the large government-run sports facility that houses the crag - CeNARD (Centro Nacional de Alto Rendimiento Deportivo). We ride around the perimeter of a huge, concrete, graffiti-covered wall that extends for miles, then turn on a street that cuts the grounds in half. Behind the walls are a full-size soccer stadium, multiple soccer fields, running tracks, indoor and outdoor pools, and training buildings for just about any sport.

Climbers received a small area adjacent to a shooting range. It is a creative solution to the vertically challenged topography: Its walls are made of real rock; It has climbs ranging from 5.7-5.12 (they use the French scale so the range is 4+ to 7c); and it enables climbers to practice the gamut of techniques.

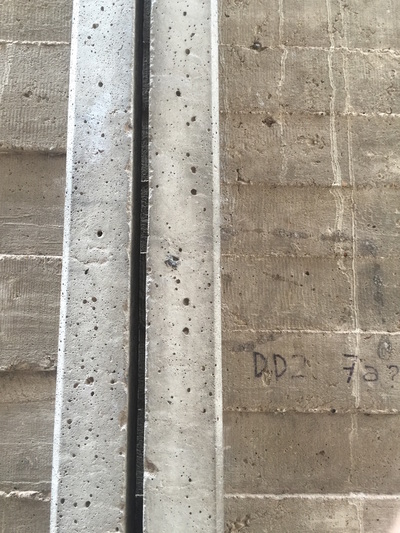

Envision a series of multiple 40-foot concrete walls that provide vertical, slightly positive, or slightly overhung angles. One side of the wall is covered in chunks of stone, while the other side is raw concrete. Both sides provide climbing of varying difficulty and styles. The concrete walls have tiny, crimpy ledges, while the rock side provides the “real rock” experience with a mixture of hold styles – side pulls, jugs, under-clings, crimps, and the occasional sloper.

Envision a series of multiple 40-foot concrete walls that provide vertical, slightly positive, or slightly overhung angles. One side of the wall is covered in chunks of stone, while the other side is raw concrete. Both sides provide climbing of varying difficulty and styles. The concrete walls have tiny, crimpy ledges, while the rock side provides the “real rock” experience with a mixture of hold styles – side pulls, jugs, under-clings, crimps, and the occasional sloper.

Face climbs are bolted but trad climbing can be practiced using one of the six finger, hand, or off-width-sized cracks. Five of the cracks are created via side-by-side placement of the walls. The finger crack is an Indian Creek-style straight as an arrow flesh ripper made of pure concrete. Walls are also positioned back-to-back and corner-to-corner allowing stemming and chimneying techniques. Midway up several walls are bolted anchors to do multi-pitch training.

When we arrive, Juan is greeted with enthusiasm by numerous climbers, male and female. He introduces me and each embraces me in Buenos Aires style, with a generous kiss on the cheek. I appreciate how welcoming this feels, far warmer than our American handshake.

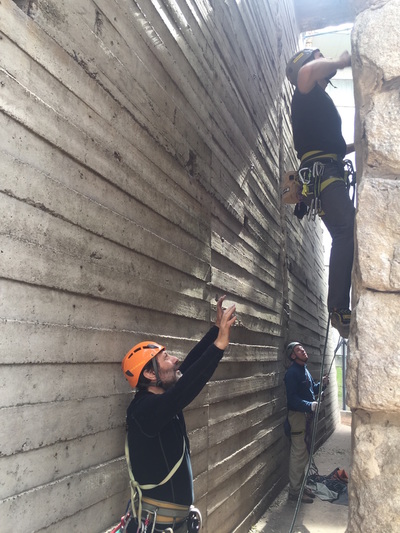

Juan and I gear up. He takes me around the back-side, clips into the safety line and rapidly climbs to the top of the wall using a metal ladder. Across the top are anchors where top ropes can be easily set up on any wall. Juan rappels down and apologizes that I will not be able lead or set up climbs because the club requires special training and testing. I reassure him that I am grateful to climb here and have zero qualms with top-roping.

I hop on the first climb, a vertical 5.9 on the stone-side of the wall. The rock has a mix of slick and featured characteristics. The mortar between the rock provides a clear visual clue of where to search for holds, but I am surprised by the lack of predictability. And, what do you know, the chunks of real rock felt like real rock. It was far less contrived than one might expect.

We also hop on a backside to climb a slightly overhanging hand crack. There are more internal ledge-like features from the rock chunks than one might experience on a typical crack, but those can be helpful when transitioning into crack climbing. The ledges can provide relief from the sharp pressure of the rocks in the crack, as well as provide rest for newly developing crack muscles. If you ignore the internal and external ledges and grabby-features you can jam all the way up.

From there we move onto a 5.10+ crimpy pump-fest on the concrete. We finish the session with a few more climbs, showing me the spectrum of what is available. Needless to say, I am impressed. I love it, in fact. This is a fun, small, human-made outdoor crag populated by an interactive and engaged community.

At the end of our day, on the way out, Juan is stopped by another climber. They rapidly converse in Spanish, far faster than I can comprehend. I notice Juan’s eyes light up with animation and then he enthusiastically embraces this other tall, bearded, muscular man. After a few more exchanged words, Juan firmly pats the man’s back and says “gracias” multiple times.

Juan turns to me with an ear-to-ear grin and says, “You will not believe this, Stefani. This is the man who helped rescue me from the climb that resulted in my amputations. I did not recognize him, because, well, I was kind of out of it then. But he recognized me. I am so grateful, now I get to thank him!” The energy of gratitude and the history of the circumstances is grounding.

We end the day restoring lost calories at a parrilla, a traditional Argentinean barbeque-style restaurant. Juan orders the mixed plate which includes just about every cut of meat and organ from a cow, cooked perfectly over coals. We chat over this heavenly-tasting, artery-clogging pile. Juan shares his plans for the near and farther-out future.

From there we move onto a 5.10+ crimpy pump-fest on the concrete. We finish the session with a few more climbs, showing me the spectrum of what is available. Needless to say, I am impressed. I love it, in fact. This is a fun, small, human-made outdoor crag populated by an interactive and engaged community.

At the end of our day, on the way out, Juan is stopped by another climber. They rapidly converse in Spanish, far faster than I can comprehend. I notice Juan’s eyes light up with animation and then he enthusiastically embraces this other tall, bearded, muscular man. After a few more exchanged words, Juan firmly pats the man’s back and says “gracias” multiple times.

Juan turns to me with an ear-to-ear grin and says, “You will not believe this, Stefani. This is the man who helped rescue me from the climb that resulted in my amputations. I did not recognize him, because, well, I was kind of out of it then. But he recognized me. I am so grateful, now I get to thank him!” The energy of gratitude and the history of the circumstances is grounding.

We end the day restoring lost calories at a parrilla, a traditional Argentinean barbeque-style restaurant. Juan orders the mixed plate which includes just about every cut of meat and organ from a cow, cooked perfectly over coals. We chat over this heavenly-tasting, artery-clogging pile. Juan shares his plans for the near and farther-out future.

In the near future - this Saturday - Juan and several other instructors are teaching two classes at CeNARD – an introductory lead climb class and a more advanced mountain guide training course. As he talks, it is clear he is excited to be involved with the Buenos Aires climbing community again and hopeful about Argentina’s future in renewable energy (the focus of his Master’s Degree and the work he is currently doing with the Government). He also expresses gratitude to be near his family.

However, it is clear something is missing. You can see it in his eyes and expressions when a “but” enters the conversation - he feels lost without the mountains and the long adventurous routes that reach into the sky and test your resolve. He tells me how he really liked living in the Pacific Northwest, with its volcanoes and North Cascade peaks. But the U.S. is not in the cards for him; He is not able to get another U.S. work visa. He wonders about his options to fulfill his passions for renewable energy and alpine climbing. Canada perhaps?

I return the conversation to Saturday’s activities and ask if I can observe the classes he is teaching. The words “Certainly!” and “I’d love that!” roll off his tongue in a lilting Castilian-Argentinian-Spanish accent. Juan suggests taking the subway from my abode and provides me with a tutorial and names of stops.

Saturday morning: I run some errands; pack for my red-eye return flight; and head over to the crag. It takes me longer to get there than anticipated. By the time I arrive the lead climbing class is over and Juan, Tota, Mortimer, Roque, and Federico (or “Fede”), the head instructor, are preparing for the mountaineering group. They kindly take a moment to welcome me in Argentinean style.

Both of the day’s classes each have approximately 20 people, an indication of the allure of climbing there. At around 1 p.m., climbers for the guide course wander through the gate, drop their bags against a fence, don their harnesses, and gather in the grass. Once the majority of the group is present Fede provides an orientation and plan for the day. He splits people equally amongst the other instructors. Groups practice knots, self-rescue, guide techniques, and 3-person multi-pitch. I enjoy watching the instruction and enthusiasm of people learning about climbing. The class is still going strong when I inform Juan it’s time for me to leave.

Juan takes a moment to separate from his group to give me a kind goodbye. I express my gratitude for his hospitality and wish him the best of success in climbing, as well as finding his next adventure and job closer to the mountains. I empathize with the conundrum of being a mountaineer and being at the mercy of his current vertically-challenged circumstances. No small crag, even if it’s a nearby cliff or hill, can substitute for the call of las montanas. But, until that day arrives, you make the best of what you’ve got. The climbers of Buenos Aires have done just that.

Resources:

Centro Andino Buenos Aires: The organization that oversees the outdoor crag at Buenos Aires, Argentina. They also train climbers and host trips. http://caba.org.ar/

However, it is clear something is missing. You can see it in his eyes and expressions when a “but” enters the conversation - he feels lost without the mountains and the long adventurous routes that reach into the sky and test your resolve. He tells me how he really liked living in the Pacific Northwest, with its volcanoes and North Cascade peaks. But the U.S. is not in the cards for him; He is not able to get another U.S. work visa. He wonders about his options to fulfill his passions for renewable energy and alpine climbing. Canada perhaps?

I return the conversation to Saturday’s activities and ask if I can observe the classes he is teaching. The words “Certainly!” and “I’d love that!” roll off his tongue in a lilting Castilian-Argentinian-Spanish accent. Juan suggests taking the subway from my abode and provides me with a tutorial and names of stops.

Saturday morning: I run some errands; pack for my red-eye return flight; and head over to the crag. It takes me longer to get there than anticipated. By the time I arrive the lead climbing class is over and Juan, Tota, Mortimer, Roque, and Federico (or “Fede”), the head instructor, are preparing for the mountaineering group. They kindly take a moment to welcome me in Argentinean style.

Both of the day’s classes each have approximately 20 people, an indication of the allure of climbing there. At around 1 p.m., climbers for the guide course wander through the gate, drop their bags against a fence, don their harnesses, and gather in the grass. Once the majority of the group is present Fede provides an orientation and plan for the day. He splits people equally amongst the other instructors. Groups practice knots, self-rescue, guide techniques, and 3-person multi-pitch. I enjoy watching the instruction and enthusiasm of people learning about climbing. The class is still going strong when I inform Juan it’s time for me to leave.

Juan takes a moment to separate from his group to give me a kind goodbye. I express my gratitude for his hospitality and wish him the best of success in climbing, as well as finding his next adventure and job closer to the mountains. I empathize with the conundrum of being a mountaineer and being at the mercy of his current vertically-challenged circumstances. No small crag, even if it’s a nearby cliff or hill, can substitute for the call of las montanas. But, until that day arrives, you make the best of what you’ve got. The climbers of Buenos Aires have done just that.

Resources:

Centro Andino Buenos Aires: The organization that oversees the outdoor crag at Buenos Aires, Argentina. They also train climbers and host trips. http://caba.org.ar/