With certain misgivings, we started moving our climbing gear, food and water to the top of the third class buttress from which the climbing would begin.

- Warren Harding

- Warren Harding

|

I never set out to be a rock climber: I was one of those kids who would climb any tree or brick surface. I thought I was afraid of heights. Who isn't? I would still climb everything.

When one first lays eyes on Yosemite, it can be overwhelming. The walls are so big that it creates an optical illusion when you are close to them. While on the climb, I recall times looking up at a section thinking it was only fifty feet or so that we had to cover. In reality it was closer to two hundred feet. When you first stand in the meadow looking at El Capitan it's hard to imagine that it is almost taller than three of our former World Trade Centers stacked end on end - and, it is two and a half miles wide. You can see people up there, but they appear as tiny specs of color with no definition of limbs. Just tiny dots. My first reaction to seeing those specks of color and movement was wanting to know how such a thing could even be possible. I observed other people in the meadow looking up at the climbers and speaking of them as being elite, somehow. They watched them like people watch rock stars on a stage. I was getting to the age where becoming a working musician, a "rock star," was becoming less likely. Here then, was a chance to be a rock star of a different sort, and I wanted to be that with all my being. So, I began to buy books, starting with Mountaineering, The Freedom of The Hills. This book showed drawings of rope configurations and people climbing using a method called "Direct Aid," where you'd use various hooks, pitons and other exotic tools with intriguing names like B.A.T. hooks. That B.A.T. was an acronym for "basically absurd technology" made it somehow more appealing, as the whole idea truly was absurd. |

I had always been a class clown and wanna-be rock star, so the swashbuckling nature of some of our pioneers like Warren Harding and John Bachar struck a chord in my soul and I knew I had found my people, at least on paper. The problem was that in 1994 there wasn't this cool tool called the Internet where you could easily connect with others and go out and do cool stuff. There were no willing partners that would consider standing on hooks and sleeping on a giant cliff that I could find, so I learned about rope soloing instead. That led me to the story of Charlie Porter and his solo first ascent of the route The Zodiac* on El Capitan. Soloing a big wall first ascent was the coolest thing I could imagine. Surely, I thought, these men and women must be the strongest people on Earth.

By chance one day at a practice crag in Big Bear, California I bumped in to a slightly older climber - Steve - who was there to do the same thing: practice rope solo big wall climbing. Once we figured out that we had come to practice one of the most obscure forms of climbing, we struck a quick friendship and decided then and there that we would climb El Capitan together. Or, at least, try.

I had, by that point, two other Yosemite big wall climbs behind me - the usual ante up routes the West Face of The Leaning Tower and the South Face of Washington Column, so I considered myself ready. Moreover, I had a Fish Products haul bag, a handful of pitons and a specialized piece of equipment called a "Wall Hauler" used to move heavy loads up the wall. We picked the "easiest" way we could see in the guide book and began attempting the Triple Direct in the spring of 1996.

We started by going up a "pitch" or two, then a bit higher, until we knew we could get to the first place to sleep (aka. bivy) in one day's worth of climbing. At that point, we decided we would "launch," going for the rest of the route. We quickly found out that the climbing was harder than expected, and surprisingly, the thought of going down, or retreating, was more terrifying than going up. So, we kept going, and eventually made it to the top.

Back then I didn't know what I didn't know, and had I known I might have spent another ten years "learning the ropes" before attempting such a serious climb as El Capitan. But there I was. I was not (and am not) a particularly gifted climber. I was sort of high strung (still working on that) and naturally bold - or careless - about my life (the lines blur when gazing at bravery or suicidal thoughts in the murky corridors of one's brain.) So, when it came time to throw down, I did and, somehow, I made it. But, it wasn't "fun."

It was five days of sun-up to sun-down labor, with a constant adrenaline rush, as if a grand piano had just crashed out of the sky right next to you, every minute of every day, all day long. I recall getting in to a state of mind that I imagined what a shaman on a serious peyote trip must be like: days of extreme effort with little food clean you out and reduce you to a feral state, and in that hour you find out what you're really are made of. The survival instincts on a big wall are such that you are performing at a level not really possible in a "safe" environment.

As a young man, my inexperienced judgement was skewed. I was more afraid in some situations than the circumstances warranted, and not afraid enough about other things. I was gripped by an irrational fear of solid gear failing and then unfazed by pulling on or touching loose rock that will actually kill you. As I have matured, I thought I would have a better experience, and that was part of my motivation for doing El Capitan again.

Over the years, I've tried to explain why we willingly march in to danger and put our lives in to the hands of our buddy, but it fails me. In this way, climbers are like front line soldiers.

There is no easy way to climb a big wall. Every pitch will force you to climb your best and smartest, even if the book says it has no "mandatory free" climbing. Plus, the difficulty ratings up there don't mean the same as they do down here. 5.8 is basically a beginner's grade, but try it with thirty pounds of equipment tangled up in slings and suddenly 5.8 rock climbing is serious business.

The bond Steve and I developed on that wall was powerful. We had to rely on and encourage each other. If you are fool enough to find yourself on The Big Stone, in that vast theatre of doom, there is nobody who will get you out of it but yourself and the buddy standing in his slings next to you.

Years have passed now and the memory has begun to fade. The lines around my eyes got deeper, the joint pains more constant and acute. I began to realize that my existence has a shelf life with an expiration date that was now becoming closer than I liked. Certain parts of my life were broken. I was a drunk and, once again, I found myself casually contemplating my own doom.

I thought that the process of getting in shape for El Capitan and being reborn sober was a path to reconciliation with my wife. That was an uncertainty, but staying stuck where I was meant certain doom and ruin.

I recognized a midlife crisis had taken its grip on me. "Is this all my life is to be?"

I believed that by re-learning to climb a big wall, I was capable of great deeds and undergoing change. I had an opportunity to gain mastery not only of the rock, but more importantly, my very life.

I decided that I would seek that shaman state again. In my mind, El Capitan became a "Great Sweat Lodge In The Sky" where I could be cleansed and renewed. I knew that through the process, should I choose to accept the mission, I would become fit again - maybe, even, I'd become more appealing to my spouse. Or perhaps, it was a cool way to end it all. Then people would say things like, "he died doing what he loved" or "he played stupid games so he won a stupid prize."

Either way, I was becoming desperate. My natural proclivity for depression was taking over and it was beginning to feel like existing was painful.

A few events made me realize that I had drank enough, so I quit. No rehab. No drama. Sometime before getting sober, I met a guy named Michael Memmel. I had made a post on Facebook about having a miracle snake oil cure for climbing rubber - a shoe renewing product - and the only person to respond was Mike. With his size 14 feet, climbing shoes were hard to come by. What I was doing, in a weird way, was fishing for a climbing partner who was better than me. I knew I wanted to climb El Capitan again, but I knew better than to be the best free climber on the team.

Michael saw my piles of gear and suggested we climb together. In passing conversation, I mentioned my goal to climb El Capitan and that I was developing a practice route at a nearby abandoned rock quarry. Strike! He said he was game and showed up to practice. This guy was clearly putting in more work than my other prospective partners.

Michael struck me as having a strong will with some narcissistic leanings. He was super careful (i.e. anal) with ropes and gear, doing some things overkill while not having enough experience to do other things that I had learned to be mandatory (such as ALWAYS using a multidirectional anchor as the first piece off the belay.) But, he was blessed with a quick wit, endless energy, and was pretty fun to hang out with. We got up Yosemite's Prow of Washington Column together, during grim heat and smoke conditions, and I developed trust in him.

It was his idea to do The Nose of El Capitan.

"I am not a good enough free climber," I told him when he made the suggestion. He assured me that he could climb 5.10 and would do all the free climbing. I knew what he didn't know about the free climbing up there, but all the pieces seemed to be in place and he was putting in the work practicing and showing himself to be much better (and twelve years younger) at free climbing than me. I knew that because of his strong will and our previous experience together, there were some things he was just going to have to learn for himself. He was simply not open to hearing certain things, and, conversely, he was thinking of items I was not. I began to recognize that his mechanical skills and somewhat selfish tendencies also made for a great, determined climbing partner.

We agreed on a date and plan.

By chance one day at a practice crag in Big Bear, California I bumped in to a slightly older climber - Steve - who was there to do the same thing: practice rope solo big wall climbing. Once we figured out that we had come to practice one of the most obscure forms of climbing, we struck a quick friendship and decided then and there that we would climb El Capitan together. Or, at least, try.

I had, by that point, two other Yosemite big wall climbs behind me - the usual ante up routes the West Face of The Leaning Tower and the South Face of Washington Column, so I considered myself ready. Moreover, I had a Fish Products haul bag, a handful of pitons and a specialized piece of equipment called a "Wall Hauler" used to move heavy loads up the wall. We picked the "easiest" way we could see in the guide book and began attempting the Triple Direct in the spring of 1996.

We started by going up a "pitch" or two, then a bit higher, until we knew we could get to the first place to sleep (aka. bivy) in one day's worth of climbing. At that point, we decided we would "launch," going for the rest of the route. We quickly found out that the climbing was harder than expected, and surprisingly, the thought of going down, or retreating, was more terrifying than going up. So, we kept going, and eventually made it to the top.

Back then I didn't know what I didn't know, and had I known I might have spent another ten years "learning the ropes" before attempting such a serious climb as El Capitan. But there I was. I was not (and am not) a particularly gifted climber. I was sort of high strung (still working on that) and naturally bold - or careless - about my life (the lines blur when gazing at bravery or suicidal thoughts in the murky corridors of one's brain.) So, when it came time to throw down, I did and, somehow, I made it. But, it wasn't "fun."

It was five days of sun-up to sun-down labor, with a constant adrenaline rush, as if a grand piano had just crashed out of the sky right next to you, every minute of every day, all day long. I recall getting in to a state of mind that I imagined what a shaman on a serious peyote trip must be like: days of extreme effort with little food clean you out and reduce you to a feral state, and in that hour you find out what you're really are made of. The survival instincts on a big wall are such that you are performing at a level not really possible in a "safe" environment.

As a young man, my inexperienced judgement was skewed. I was more afraid in some situations than the circumstances warranted, and not afraid enough about other things. I was gripped by an irrational fear of solid gear failing and then unfazed by pulling on or touching loose rock that will actually kill you. As I have matured, I thought I would have a better experience, and that was part of my motivation for doing El Capitan again.

Over the years, I've tried to explain why we willingly march in to danger and put our lives in to the hands of our buddy, but it fails me. In this way, climbers are like front line soldiers.

There is no easy way to climb a big wall. Every pitch will force you to climb your best and smartest, even if the book says it has no "mandatory free" climbing. Plus, the difficulty ratings up there don't mean the same as they do down here. 5.8 is basically a beginner's grade, but try it with thirty pounds of equipment tangled up in slings and suddenly 5.8 rock climbing is serious business.

The bond Steve and I developed on that wall was powerful. We had to rely on and encourage each other. If you are fool enough to find yourself on The Big Stone, in that vast theatre of doom, there is nobody who will get you out of it but yourself and the buddy standing in his slings next to you.

Years have passed now and the memory has begun to fade. The lines around my eyes got deeper, the joint pains more constant and acute. I began to realize that my existence has a shelf life with an expiration date that was now becoming closer than I liked. Certain parts of my life were broken. I was a drunk and, once again, I found myself casually contemplating my own doom.

I thought that the process of getting in shape for El Capitan and being reborn sober was a path to reconciliation with my wife. That was an uncertainty, but staying stuck where I was meant certain doom and ruin.

I recognized a midlife crisis had taken its grip on me. "Is this all my life is to be?"

I believed that by re-learning to climb a big wall, I was capable of great deeds and undergoing change. I had an opportunity to gain mastery not only of the rock, but more importantly, my very life.

I decided that I would seek that shaman state again. In my mind, El Capitan became a "Great Sweat Lodge In The Sky" where I could be cleansed and renewed. I knew that through the process, should I choose to accept the mission, I would become fit again - maybe, even, I'd become more appealing to my spouse. Or perhaps, it was a cool way to end it all. Then people would say things like, "he died doing what he loved" or "he played stupid games so he won a stupid prize."

Either way, I was becoming desperate. My natural proclivity for depression was taking over and it was beginning to feel like existing was painful.

A few events made me realize that I had drank enough, so I quit. No rehab. No drama. Sometime before getting sober, I met a guy named Michael Memmel. I had made a post on Facebook about having a miracle snake oil cure for climbing rubber - a shoe renewing product - and the only person to respond was Mike. With his size 14 feet, climbing shoes were hard to come by. What I was doing, in a weird way, was fishing for a climbing partner who was better than me. I knew I wanted to climb El Capitan again, but I knew better than to be the best free climber on the team.

Michael saw my piles of gear and suggested we climb together. In passing conversation, I mentioned my goal to climb El Capitan and that I was developing a practice route at a nearby abandoned rock quarry. Strike! He said he was game and showed up to practice. This guy was clearly putting in more work than my other prospective partners.

Michael struck me as having a strong will with some narcissistic leanings. He was super careful (i.e. anal) with ropes and gear, doing some things overkill while not having enough experience to do other things that I had learned to be mandatory (such as ALWAYS using a multidirectional anchor as the first piece off the belay.) But, he was blessed with a quick wit, endless energy, and was pretty fun to hang out with. We got up Yosemite's Prow of Washington Column together, during grim heat and smoke conditions, and I developed trust in him.

It was his idea to do The Nose of El Capitan.

"I am not a good enough free climber," I told him when he made the suggestion. He assured me that he could climb 5.10 and would do all the free climbing. I knew what he didn't know about the free climbing up there, but all the pieces seemed to be in place and he was putting in the work practicing and showing himself to be much better (and twelve years younger) at free climbing than me. I knew that because of his strong will and our previous experience together, there were some things he was just going to have to learn for himself. He was simply not open to hearing certain things, and, conversely, he was thinking of items I was not. I began to recognize that his mechanical skills and somewhat selfish tendencies also made for a great, determined climbing partner.

We agreed on a date and plan.

Day 1: Finally On the Wall - Or Maybe Not

I picked up Michael at his place in at about 6 p.m.

We drove until I was about to fall asleep, then I pulled over. We "sleep" in the truck seats, finding enough comfort to get an hour or two of shut eye. I dream of voices high above shouting "slack!" and of a gargoyle with a man's face sitting at a place called The Glowering Spot. I stirred awake from restlessness for the climb and discomfort from the seat and we moved on.

I picked up Michael at his place in at about 6 p.m.

We drove until I was about to fall asleep, then I pulled over. We "sleep" in the truck seats, finding enough comfort to get an hour or two of shut eye. I dream of voices high above shouting "slack!" and of a gargoyle with a man's face sitting at a place called The Glowering Spot. I stirred awake from restlessness for the climb and discomfort from the seat and we moved on.

Hover or click on photos for captions, click to enlarge

Despite a new permit system for overnight climbers, we arrived in Yosemite to find that a giant crowd was on our intended path. There were teams at every belay, teams going up this start, that start, coming down, going up, waiting, passing, taking forever, or moving fast. One curious portaledge camp, set up five hundred feet above at a place called Sickle Ledge, did not appear to move for the three days it took us to finally get started.

We decided that the only logical plan of attack was to get on the route and not come down until we were done - to take our place in the conga line and do the dance. That meant bringing what seemed like a giant amount of water and food and doing what everybody else was not doing, which was to start from the ground and take our stuff with us (most people climb up 500 feet to Sickle Ledge, then haul their stuff up from there. But this requires more static ropes than we had.)

It was such a sight with all the teams, including some particular morons who dropped both large rocks and their haul bags. Someone had made a Facebook post about that incident and, it was with great hilarity that we found ourselves in the picture. That was after hiking 4-5 loads of food and water to the base, sorting gear, packing up, and patiently waiting for hours at a time for the line to progress. Upon reflection, it was a rather grotesque scene, like the crowds on Everest. But even the rangers told us that if we wanted to climb The Nose we "better get on it."

We decided that the only logical plan of attack was to get on the route and not come down until we were done - to take our place in the conga line and do the dance. That meant bringing what seemed like a giant amount of water and food and doing what everybody else was not doing, which was to start from the ground and take our stuff with us (most people climb up 500 feet to Sickle Ledge, then haul their stuff up from there. But this requires more static ropes than we had.)

It was such a sight with all the teams, including some particular morons who dropped both large rocks and their haul bags. Someone had made a Facebook post about that incident and, it was with great hilarity that we found ourselves in the picture. That was after hiking 4-5 loads of food and water to the base, sorting gear, packing up, and patiently waiting for hours at a time for the line to progress. Upon reflection, it was a rather grotesque scene, like the crowds on Everest. But even the rangers told us that if we wanted to climb The Nose we "better get on it."

Hover or click on photos for captions, click to enlarge

I reassured Michael that the crowds would thin out dramatically by the halfway point, as the bottom part of the route was complicated and involved multiple pendulums and a dreaded chimney section that involves easy yet unprotected climbing for enough distance to eat you should you fall.

The sight of not one, but two, giant haul bags at the top of the starting buttress was no doubt met with snickers. But, we waited out the bailers and failers and let the sailors sail. We saw times range from seven days on the wall for a successful team to five days by a team forced to retreat from El Cap Tower, to some maniacs doing the whole wall in five hours.

For some reason the first 180 feet (55 meters) of The Nose do not count, even though it would be a nasty sight if you fell before the start. Right as we got to the top of the starting buttress, near disaster struck. As, we were carrying an abusive amount of water our load was extremely heavy, so we had agreed to use a robust mechanical advantage of 4-1 on our hauling system. It worked great, moving the 350+ pound (159 kilograms) load up the wall with enough strength to not feel the haul bags catch on stuff like trees and rocks. It pulled the bags so hard that the rope core-shot and the sheath failed, right as the bags neared the belay.

The sight of not one, but two, giant haul bags at the top of the starting buttress was no doubt met with snickers. But, we waited out the bailers and failers and let the sailors sail. We saw times range from seven days on the wall for a successful team to five days by a team forced to retreat from El Cap Tower, to some maniacs doing the whole wall in five hours.

For some reason the first 180 feet (55 meters) of The Nose do not count, even though it would be a nasty sight if you fell before the start. Right as we got to the top of the starting buttress, near disaster struck. As, we were carrying an abusive amount of water our load was extremely heavy, so we had agreed to use a robust mechanical advantage of 4-1 on our hauling system. It worked great, moving the 350+ pound (159 kilograms) load up the wall with enough strength to not feel the haul bags catch on stuff like trees and rocks. It pulled the bags so hard that the rope core-shot and the sheath failed, right as the bags neared the belay.

Hover or click on photos for captions, click to enlarge

I glanced down at tourists around the base who were looking up at where Free Solo and The Dawn Wall were filmed, wondering if they knew how close little Jonny - perhaps innocently eating a peanut butter and jelly sandwich - was to doom, at risk of being pulverized by a pair of haul bags weighing 350 pounds or more... . I quickly slapped on an emergency sling to back up the giant load. Micheal showed off his mechanical art skills and repositioned the inverted rope catch of our haul to a place on the rope where the sheath was not exposed.

We knew this was only a temporary fix, so we left our stuff at the top of the buttress and went back down to Curry Village to buy a new static line. By the time we arrived, though, everything was closed. Disappointing.

In a different era of my life, I would have told myself it's early enough to get drunk one last time before fully committing to the vertical abyss. Instead, we settled for hot food and showers - sans the booze. Over dinner, we spoke hastily about time and getting back on the wall. We decided to forgo buying a new static line and use my 70-meter climbing rope as the new lead line and we'd use Mike's climbing rope as the haul line. This arrangement would allow us to get climbing first thing in the morning.

Sleep was fleeting - again - filled with the sounds of clanging iron and climbers shouting to each other. My dreams are always the same before blasting off on a big climb.

Day 2: Static Lines and Smoke

Back on the wall, we led up to a new high point. The sport rope was extra stretchy to ascend, bouncing me up and down with its dynamic nature. As I weighted the rope, with each bounce rubbing back-and-forth against the granite, I imagined rough edges cutting the sheath and exposing the core again. In my mind's eye I saw myself falling only to bounce off the rock below. My mind does not let go of this vision - I hear a wet snapping of bones and there is a splash of color as my body impacts the ground below - in front of Little Jonny and his Pb&J. I imagine Little Jonny doesn't react much, as he's probably been desensitized by violent video games, but his parents though... they'd be mortified.

"Mike! Fuck this! Let's go get a new rope!"

So - again - we left our massive load of gear, known in our sport as a "junk show," at the rather comical spot of the top of pitch two. There's no doubt at all we are now the laughing stock of all the climbers in Yosemite. I look at our junk show as we walk back, yet again, to the truck for another mindless loop around the valley to buy a static rope. I felt embarrassed. Mike didn't. He was on El Capitan in Yosemite, living the dream, hooting and whooping it up to all who will whoop or monkey call in return.

There were no rooms at the inn so we bivied near the base of the climb after buying a new static rope for hauling. What sleep I got was filled again with the sounds of those old climbers - "On belay!" yells one. "Climbing!" responds the other, more distant voice, higher up the wall.

There were controlled burns all around the park and we felt as if the park service was trying to burn us out, ruining the air quality and throwing in yet another bit of chaos (which we eventually came to call Jingus).

We both asked aloud, "What the hell are they thinking? We are trying to climb here!"

Finally, we took off up the wall towards our junk show.

We knew this was only a temporary fix, so we left our stuff at the top of the buttress and went back down to Curry Village to buy a new static line. By the time we arrived, though, everything was closed. Disappointing.

In a different era of my life, I would have told myself it's early enough to get drunk one last time before fully committing to the vertical abyss. Instead, we settled for hot food and showers - sans the booze. Over dinner, we spoke hastily about time and getting back on the wall. We decided to forgo buying a new static line and use my 70-meter climbing rope as the new lead line and we'd use Mike's climbing rope as the haul line. This arrangement would allow us to get climbing first thing in the morning.

Sleep was fleeting - again - filled with the sounds of clanging iron and climbers shouting to each other. My dreams are always the same before blasting off on a big climb.

Day 2: Static Lines and Smoke

Back on the wall, we led up to a new high point. The sport rope was extra stretchy to ascend, bouncing me up and down with its dynamic nature. As I weighted the rope, with each bounce rubbing back-and-forth against the granite, I imagined rough edges cutting the sheath and exposing the core again. In my mind's eye I saw myself falling only to bounce off the rock below. My mind does not let go of this vision - I hear a wet snapping of bones and there is a splash of color as my body impacts the ground below - in front of Little Jonny and his Pb&J. I imagine Little Jonny doesn't react much, as he's probably been desensitized by violent video games, but his parents though... they'd be mortified.

"Mike! Fuck this! Let's go get a new rope!"

So - again - we left our massive load of gear, known in our sport as a "junk show," at the rather comical spot of the top of pitch two. There's no doubt at all we are now the laughing stock of all the climbers in Yosemite. I look at our junk show as we walk back, yet again, to the truck for another mindless loop around the valley to buy a static rope. I felt embarrassed. Mike didn't. He was on El Capitan in Yosemite, living the dream, hooting and whooping it up to all who will whoop or monkey call in return.

There were no rooms at the inn so we bivied near the base of the climb after buying a new static rope for hauling. What sleep I got was filled again with the sounds of those old climbers - "On belay!" yells one. "Climbing!" responds the other, more distant voice, higher up the wall.

There were controlled burns all around the park and we felt as if the park service was trying to burn us out, ruining the air quality and throwing in yet another bit of chaos (which we eventually came to call Jingus).

We both asked aloud, "What the hell are they thinking? We are trying to climb here!"

Finally, we took off up the wall towards our junk show.

Hover or click on photos for captions, click to enlarge

Day 4: Free Climbing - Or Is It?

We got to Sickle Ledge and set up our portaledges. At this point, we were now committed to the wall and would not come down unless we had to.

We realized that many of the faster parties were skipping much of the climbing by "cheating" by pulling on bits of rope left hanging from bolts to bypass the original difficulties. In a game with no rules, where the ethic is basically that what happens between belays is nobody's business but the climber, this still strikes me as a certain level of bullshit. We are trying to climb the actual route, from the ground, with nothing but a topo map to guide us.

We met a team of mostly female climbers who were super nice. They were moving faster and with definitely better fashion style than my climbing partner and I. We exchanged hoots and hollers with these fellow travelers and wished each other success. Another team came through and were in stark contrast to the team of ladies. These guys were rude and obnoxious and climbed in a sloppy style above us that made us nervous that one of the dudes might actually fall on us. We nicknamed him "Doofus Beefcake."

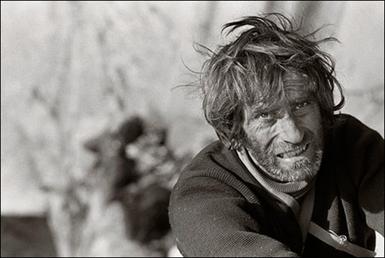

I think right about then was when I began to realize that my partner looked very much like the author of the route, Warren Harding himself. I thought of a quote from Warren's book Downward Bound - “With Warren there was no turning around. He had that kind of total dedication that takes you to the top.” Michael seemed that way too.

Micheal and I shared a mutual inspiration from the author of the climb. Warren was a proud visionary. Our time on the climb would require Mike and me to have total dedication that was but a shadow of that required to establish this path.

We got to Sickle Ledge and set up our portaledges. At this point, we were now committed to the wall and would not come down unless we had to.

We realized that many of the faster parties were skipping much of the climbing by "cheating" by pulling on bits of rope left hanging from bolts to bypass the original difficulties. In a game with no rules, where the ethic is basically that what happens between belays is nobody's business but the climber, this still strikes me as a certain level of bullshit. We are trying to climb the actual route, from the ground, with nothing but a topo map to guide us.

We met a team of mostly female climbers who were super nice. They were moving faster and with definitely better fashion style than my climbing partner and I. We exchanged hoots and hollers with these fellow travelers and wished each other success. Another team came through and were in stark contrast to the team of ladies. These guys were rude and obnoxious and climbed in a sloppy style above us that made us nervous that one of the dudes might actually fall on us. We nicknamed him "Doofus Beefcake."

I think right about then was when I began to realize that my partner looked very much like the author of the route, Warren Harding himself. I thought of a quote from Warren's book Downward Bound - “With Warren there was no turning around. He had that kind of total dedication that takes you to the top.” Michael seemed that way too.

Micheal and I shared a mutual inspiration from the author of the climb. Warren was a proud visionary. Our time on the climb would require Mike and me to have total dedication that was but a shadow of that required to establish this path.

Hover or click on photos for captions, click to enlarge

Days 5: Introducing Mr. Jingus

We noticed a trend. We used rope buckets to keep the ropes organized, which worked great on paper. The idea is, you stack the two hundred-foot ropes inside these buckets, and everything is mellow but, once a certain point is reached where the weight of the rope hanging out of the bag, the weight gets to be so much that it pulls the rest of the rope out. Then you hear this cringe-worthy sound - kind of like a dog dragging its itchy ass across the carpet - and the rope jumps out of the bag and begins to unravel at warp speed forcing you to desperately grab it and restack it again.

I'm trying to not curse, so I shout "Jingus H!" instead of "Jesus H!"

"What is Jingus?" Michael asks.

"Jingus is chaos. Tangles in our stuff. First name is Cluster, middle name rhymes with duck. Mr. C.F. Jingus to you!"

I'm was flustered as I stacked the rope again. I tried to mirror Michael's can-do attitude and fixed the pitch above Sickle Ledge so we would have a new high point in the morning. Michael seemed happy that I was free climbing - except I dropped his spare pulley, which sort of made him tense. Michael is completely different from me; He has all his gear marked so it doesn't get mixed up with my stuff. At the end of a climb I would just dump all my unmarked gear in a pile and let him take what he thinks is his. It's just stuff to me.

We noticed a trend. We used rope buckets to keep the ropes organized, which worked great on paper. The idea is, you stack the two hundred-foot ropes inside these buckets, and everything is mellow but, once a certain point is reached where the weight of the rope hanging out of the bag, the weight gets to be so much that it pulls the rest of the rope out. Then you hear this cringe-worthy sound - kind of like a dog dragging its itchy ass across the carpet - and the rope jumps out of the bag and begins to unravel at warp speed forcing you to desperately grab it and restack it again.

I'm trying to not curse, so I shout "Jingus H!" instead of "Jesus H!"

"What is Jingus?" Michael asks.

"Jingus is chaos. Tangles in our stuff. First name is Cluster, middle name rhymes with duck. Mr. C.F. Jingus to you!"

I'm was flustered as I stacked the rope again. I tried to mirror Michael's can-do attitude and fixed the pitch above Sickle Ledge so we would have a new high point in the morning. Michael seemed happy that I was free climbing - except I dropped his spare pulley, which sort of made him tense. Michael is completely different from me; He has all his gear marked so it doesn't get mixed up with my stuff. At the end of a climb I would just dump all my unmarked gear in a pile and let him take what he thinks is his. It's just stuff to me.

Hover or click on photos for captions, click to enlarge

Day 6ish: Mr. Jingus Pays More Visits

This was the first of our all-nighters. At some point the haul system got jammed and we were faced with being stuck.

I had led a pitch and was hauling when the rope stopped moving in the pulley. The full moon was out and I hear Mr. Jingus whisper, "Hey you idiot, you better back those bags up, as your shit is stuck." I tell Mike what's up but he is still cleaning the pitch below me, and not able to assist just yet. Then, I make a rooky error and I open the main carabiner holding our giant junkshow on the wall to place a back-up sling. It was hard to open and even harder to close. I realize that I just about dropped the haul bags, now almost one thousand feet, to the ground. One simply does not open a weighted carabiner. But I just did.

"Holy shit!" I yell out of panic at what I had just done - I saw the carabiner start to bend and prayed it wouldn't break and release a 350-pound missile to the ground. I yelled for Mike to hurry and somewhere in the air behind me, or in that void between my ears, Mr. Jingus was laughing. He was very amused.

When Michael arrived, we slapped together a new haul system out of spare parts, used a hammer to unjam the doomed Wall Hauler and, then, finally, six hours later we finished the pitch. The stars faded from the sky and the sun rose. Exhausted, we were coming in hot to Dolt Tower and decided a rest day was in order.

This was the first of our all-nighters. At some point the haul system got jammed and we were faced with being stuck.

I had led a pitch and was hauling when the rope stopped moving in the pulley. The full moon was out and I hear Mr. Jingus whisper, "Hey you idiot, you better back those bags up, as your shit is stuck." I tell Mike what's up but he is still cleaning the pitch below me, and not able to assist just yet. Then, I make a rooky error and I open the main carabiner holding our giant junkshow on the wall to place a back-up sling. It was hard to open and even harder to close. I realize that I just about dropped the haul bags, now almost one thousand feet, to the ground. One simply does not open a weighted carabiner. But I just did.

"Holy shit!" I yell out of panic at what I had just done - I saw the carabiner start to bend and prayed it wouldn't break and release a 350-pound missile to the ground. I yelled for Mike to hurry and somewhere in the air behind me, or in that void between my ears, Mr. Jingus was laughing. He was very amused.

When Michael arrived, we slapped together a new haul system out of spare parts, used a hammer to unjam the doomed Wall Hauler and, then, finally, six hours later we finished the pitch. The stars faded from the sky and the sun rose. Exhausted, we were coming in hot to Dolt Tower and decided a rest day was in order.

The post mortem report on our haul system failure showed two fatal problems: our zed chord for the 2-1 was so small in diameter it was ruining the double pully, and the Wall Hauler was not able to handle the side loads caused by our heavy bags needing to be lowered out on the traverses. We feel as if we had handled a potentially dangerous situation smartly and that Mr. C.F. Jingus could go piss up somebody else and their rope.

That night I thought about the many hundreds of pieces of climbing equipment jammed into the cracks. In some stretches the cracks have gear very deep inside, so far beyond use its unimaginable how it would get there. If one were to pick El Capitan up and shake it out upside down thousands of pounds of gear and rope would excrete out, abandoned to the worry and financial stress of past climbers.

In my musings, it occurred to me that some human debris is "natural" and has its rightful place on the wall. The stuck gear inside the cracks stand as relics to the struggles of others who had gone before; But the trash and empty water bottles left by Doofus Beafcake and his consorts on Dolt Tower could not remain as a testament to modern man's trashy nature. I drank the remaining water stash and took the empties with me, now feeling something closer to scorn for Mr. Beefcake.

That night I thought about the many hundreds of pieces of climbing equipment jammed into the cracks. In some stretches the cracks have gear very deep inside, so far beyond use its unimaginable how it would get there. If one were to pick El Capitan up and shake it out upside down thousands of pounds of gear and rope would excrete out, abandoned to the worry and financial stress of past climbers.

In my musings, it occurred to me that some human debris is "natural" and has its rightful place on the wall. The stuck gear inside the cracks stand as relics to the struggles of others who had gone before; But the trash and empty water bottles left by Doofus Beafcake and his consorts on Dolt Tower could not remain as a testament to modern man's trashy nature. I drank the remaining water stash and took the empties with me, now feeling something closer to scorn for Mr. Beefcake.

Day 7: Nightime Pathways - Sickle to Dolt Tower

This day began with what would become a trend - starting late. We had been up late dealing with the haul bag the night before, so we were very tired. Some guys from Chile came through playing some interesting reggae. We watched them move past. They were very professional and fast. I joked with them in what little Spanish I know.

Dolt Tower is a very large flat platform where two people can comfortably set up their camp, which for us involved hanging beds called portaledges. We were now approximately 1,000 feet above the valley floor. The fires had lit some tall pine trees which burned throughout the night like candles from the trunk to the top of the tree. Fortunately, that was the last of the smoke, as the controlled fire burning was over.

As our climbing continued, we moved to the next higher ledge, shifting from a slow pace to an "oh-my-God-hurry" pace as thunderclouds rolled in and threatened rain. We were at El Cap Tower. The Texas flake sits right above, looking like it's forty feet tall (it's more like one hundred and fifty). The infamous King Swing was next after the fun and easy Boot Flake pitch. We were now feeling like terrestrial astronauts, way up high in space, and at the same time looking like coal miners with our headlamps, helmets, and dirty faces. I got to lead the Boot Flake and replicate the famous picture from the 1950's by William Fuhrer and the most recent version done by Alex Honnold - except it was Michael - lying on top of the Texas Chimney.

This day began with what would become a trend - starting late. We had been up late dealing with the haul bag the night before, so we were very tired. Some guys from Chile came through playing some interesting reggae. We watched them move past. They were very professional and fast. I joked with them in what little Spanish I know.

Dolt Tower is a very large flat platform where two people can comfortably set up their camp, which for us involved hanging beds called portaledges. We were now approximately 1,000 feet above the valley floor. The fires had lit some tall pine trees which burned throughout the night like candles from the trunk to the top of the tree. Fortunately, that was the last of the smoke, as the controlled fire burning was over.

As our climbing continued, we moved to the next higher ledge, shifting from a slow pace to an "oh-my-God-hurry" pace as thunderclouds rolled in and threatened rain. We were at El Cap Tower. The Texas flake sits right above, looking like it's forty feet tall (it's more like one hundred and fifty). The infamous King Swing was next after the fun and easy Boot Flake pitch. We were now feeling like terrestrial astronauts, way up high in space, and at the same time looking like coal miners with our headlamps, helmets, and dirty faces. I got to lead the Boot Flake and replicate the famous picture from the 1950's by William Fuhrer and the most recent version done by Alex Honnold - except it was Michael - lying on top of the Texas Chimney.

Hover or click on photos for captions, click to enlarge

Our next push involved a long day and a hanging camp that was very hard to set up and tear down. For the second time on the climb, words were exchanged. At some point in a thing like this you yell at each other. It usually involves time - either having to hurry or having to wait. But, we reset after a tough day and somehow, this exchange created a new, improved dialog between us and we move up a better team for it. Or, perhaps we just feared the rage we had momentarily invoked in each other, and tried to keep that in the bag.

The stretch from El Cap Tower to The Grey Bands involves the last of the pendulums and traverses, which are time consuming and complicated. With big wall climbing you sometimes end up climbing a pitch several times - once the leader reaches the belay spot, the second ascends the line and cleans the gear. Then the haul bags are brought up and the second rappels down to maneuver the haul bags if they get stuck on rock outcroppings or tree branches. With traverses and pendulum swings, this process gets even more complex. To top it off, it seems like you often end up at a windy spot in the middle of broken rock with no good place to stand or unpack, which is physically demanding and uncomfortable compared to having a nice ledge.

The later it gets the longer things take, as the energy is diminished. We kept thinking we'd have time to eat and consume water, but more often than not we were climbing hungry, thirsty, and pressed for time.

It was my turn to lead and it was almost full-dark. I looked to the sky, hoping to see a moon glow rising over the Cathedral Peaks, but that would not be for another two hours, so I set out. The topo called for a long lead on my pitch 15, finishing with an innocent looking lower out to a ledge where we expected to be able to set up our camp. The ratings suggested an easy passage, but in the dark it gets confusing. Usually you follow the cracks, and this was the case here, but it was dark and I couldn't see the next placement without getting way up high, which is physically taxing.

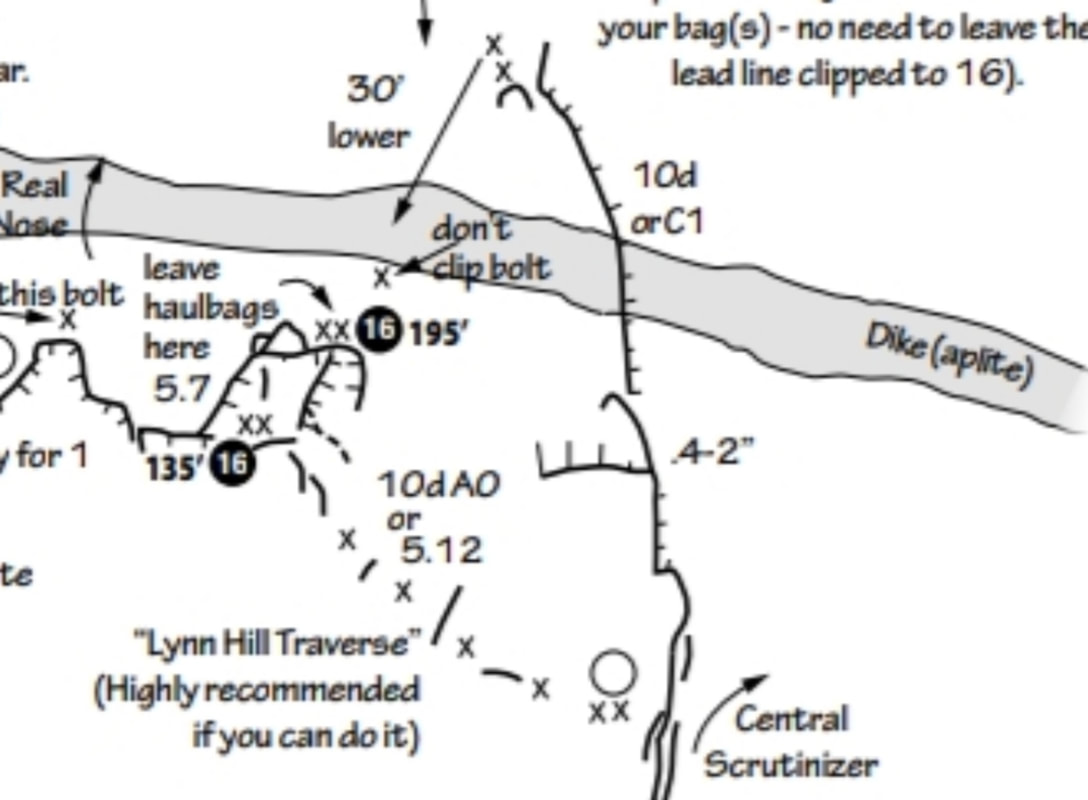

I paused in the middle of my lead and consulted a paper topo map.

The stretch from El Cap Tower to The Grey Bands involves the last of the pendulums and traverses, which are time consuming and complicated. With big wall climbing you sometimes end up climbing a pitch several times - once the leader reaches the belay spot, the second ascends the line and cleans the gear. Then the haul bags are brought up and the second rappels down to maneuver the haul bags if they get stuck on rock outcroppings or tree branches. With traverses and pendulum swings, this process gets even more complex. To top it off, it seems like you often end up at a windy spot in the middle of broken rock with no good place to stand or unpack, which is physically demanding and uncomfortable compared to having a nice ledge.

The later it gets the longer things take, as the energy is diminished. We kept thinking we'd have time to eat and consume water, but more often than not we were climbing hungry, thirsty, and pressed for time.

It was my turn to lead and it was almost full-dark. I looked to the sky, hoping to see a moon glow rising over the Cathedral Peaks, but that would not be for another two hours, so I set out. The topo called for a long lead on my pitch 15, finishing with an innocent looking lower out to a ledge where we expected to be able to set up our camp. The ratings suggested an easy passage, but in the dark it gets confusing. Usually you follow the cracks, and this was the case here, but it was dark and I couldn't see the next placement without getting way up high, which is physically taxing.

I paused in the middle of my lead and consulted a paper topo map.

I could see a set of bolts, and the tired part of me wanted to stop there. Mr. Jingus suggested this was a great idea. "Look, you dumbfuck, you are supposed to go left. You don't know what you are doing or where you are going."

I started to move up and left, then a large spider stepped towards me as if to block my path. "Go right, stupid," the spider seemed to say. I recalled some words on the topo about not clipping a bolt. Was that tempting bolt to my left the one I should avoid? I was exhausted and unsure, but I listened to the spider and ignored Mr. Jingus and went right into a sea of dark unknown.

Bugs were attracted to my headlamp, buzzing my face and flying up my nose. The unfortunate ones who go for glory inside my mouth are spat out in a ruin of large wings. My nose was dry and I expelled unspeakables out each nostril. I collected my courage to head up and over some small roofs where, much to my relief, a bolt - the correct bolt - finally awaited me. I silently thanked the spider.

My water was running low and my throat was dry. I was thinking my climbing harness and clothes were stretching out, as my pants wanted to fall off. Conversely my feet were screaming as my boots felt like they shrunk. It turns out I lost sixteen pounds over the course of the climb.

At this point both Mike and I were in constant pain. His elbow was swollen. My left knee was singing. Our cuticles and skin have become cracked and bleeding. Even touching ourselves to scratch an itch caused us to draw a sharp breath and comment something like, "holy shit, everything hurts."

The gear we used to move up seemed to catch on everything making every step up a challenge to just stay untangled. Yet, we were still far from the top. In the moment of climbing upwards, the leader's pain fades in the wash of adrenaline, while the belayer moans below in inescapable agony. The hips hurt from hauling. The thighs were squeezed by our harnesses. The tops of my toes were rubbed raw and bleeding. But, when it's my turn to climb, I don't feel anything.

I called for tension and had Michael take my weight on the lead rope. He was far below but our voices carried well now that the wind stood still. The moon finally arrived and now helped light my path. I could see a small ledge below and off to the side. Although it was not on the topo, I decided it was going to be our bivy, but it would require some swing-tatics to access. I had Michael lower me down about thirty feet and then called for him to stop. I tried to use friction to ooze across the wall to the left to the ledge. I slipped and swung back to the right. I turned my body to bounce off a left facing corner with my feet and protect my vitals.

At that point I realized that I must actually run back and forth in the dark to gain momentum, and worse, I was too low on the rope. I used rope ascenders to climb up five feet and started swinging side-to-side. I grabbed a few times at an edge and, when I was able to hold on long enough, pulled with all my might. Then I flopped over the edge to what would be our camp: a six-inch (15 centimeter) wide sloping shelf that was tough to balance on. With two thousand feet below my boots, I sometimes told myself, "if you fall fifty feet you will die, so what is two thousand feet?" The answer is of course: semper mortis.

We set up camp with the promise of no four a.m. alarm clock from Michael's phone.

Day 8: The Headwall

We rested a bit and fate had it that after Mike led us to the Great Roof it was dark again. It was my turn so I started up into the famous arch by headlamp. Next was the Pancake Flake, which is easy, as long as you have forty camming devices in the .75 size, which of course I did not. I moved up laboriously having to make a half dozen pieces work for protection. We neared Camp 5 and, for the first time, getting to the top in one push seemed possible.

I started to move up and left, then a large spider stepped towards me as if to block my path. "Go right, stupid," the spider seemed to say. I recalled some words on the topo about not clipping a bolt. Was that tempting bolt to my left the one I should avoid? I was exhausted and unsure, but I listened to the spider and ignored Mr. Jingus and went right into a sea of dark unknown.

Bugs were attracted to my headlamp, buzzing my face and flying up my nose. The unfortunate ones who go for glory inside my mouth are spat out in a ruin of large wings. My nose was dry and I expelled unspeakables out each nostril. I collected my courage to head up and over some small roofs where, much to my relief, a bolt - the correct bolt - finally awaited me. I silently thanked the spider.

My water was running low and my throat was dry. I was thinking my climbing harness and clothes were stretching out, as my pants wanted to fall off. Conversely my feet were screaming as my boots felt like they shrunk. It turns out I lost sixteen pounds over the course of the climb.

At this point both Mike and I were in constant pain. His elbow was swollen. My left knee was singing. Our cuticles and skin have become cracked and bleeding. Even touching ourselves to scratch an itch caused us to draw a sharp breath and comment something like, "holy shit, everything hurts."

The gear we used to move up seemed to catch on everything making every step up a challenge to just stay untangled. Yet, we were still far from the top. In the moment of climbing upwards, the leader's pain fades in the wash of adrenaline, while the belayer moans below in inescapable agony. The hips hurt from hauling. The thighs were squeezed by our harnesses. The tops of my toes were rubbed raw and bleeding. But, when it's my turn to climb, I don't feel anything.

I called for tension and had Michael take my weight on the lead rope. He was far below but our voices carried well now that the wind stood still. The moon finally arrived and now helped light my path. I could see a small ledge below and off to the side. Although it was not on the topo, I decided it was going to be our bivy, but it would require some swing-tatics to access. I had Michael lower me down about thirty feet and then called for him to stop. I tried to use friction to ooze across the wall to the left to the ledge. I slipped and swung back to the right. I turned my body to bounce off a left facing corner with my feet and protect my vitals.

At that point I realized that I must actually run back and forth in the dark to gain momentum, and worse, I was too low on the rope. I used rope ascenders to climb up five feet and started swinging side-to-side. I grabbed a few times at an edge and, when I was able to hold on long enough, pulled with all my might. Then I flopped over the edge to what would be our camp: a six-inch (15 centimeter) wide sloping shelf that was tough to balance on. With two thousand feet below my boots, I sometimes told myself, "if you fall fifty feet you will die, so what is two thousand feet?" The answer is of course: semper mortis.

We set up camp with the promise of no four a.m. alarm clock from Michael's phone.

Day 8: The Headwall

We rested a bit and fate had it that after Mike led us to the Great Roof it was dark again. It was my turn so I started up into the famous arch by headlamp. Next was the Pancake Flake, which is easy, as long as you have forty camming devices in the .75 size, which of course I did not. I moved up laboriously having to make a half dozen pieces work for protection. We neared Camp 5 and, for the first time, getting to the top in one push seemed possible.

Hover or click on photos for captions, click to enlarge

We were exhausted. But, we had no choice to start early. I was feeling every one of my 52 years. I had now reached the point in the climb where I had been before, 26 years ago. We discussed the best plan, and I was forced to admit that the best plan was to turn over my defacto position as leader of this expedition to Michael. I asked him to finish the climb by leading the last six pitches, which constitutes the headwall. I had been there, done that, and I had little juice left to do it again. But, in some measure of support, I was able to give precise beta on what size gear to use and when he would find it and where to cut right. Even though the climb goes over literally thousands of moves, many of them were burned in to my mind from 1996, to the point where I could have organized the protection gear to be used in close order.

Michael had that kind of total dedication that takes you to the top. Aside from one snag with our haul bags, the rest of the headwall went down without complication. Maybe Mr. Jingus was getting old too - or at least took a nap.

On the last pitch, it was night time again. The bags swung out away from me, revealing the moon in the background. It was a pretty amazing sight. By the time we both made it to the high point and the bags were up, the sun was rising. Another all-nighter. I was broken. I was so tired I could barely move. Then, Mr. Jingus stirred from his slumber, tangling the ropes one last time. I just wanted to lay down, but the climb was not over - we still had to get our bags up and over the top and we still had a descent.

While pulling up the bags, I looked down to try to see other climbers below. They were dots of color lost in the folding waves of granite. This time below us, instead of above.

We are kings.

We were quiet, taking in these last moments. With my grey wind jacket and the white ropes piled on my shoulders, I looked like some mythical sea creature with two jutting headlamps for eyes, swimming up out of some deep water. This part of the climb was over and I now stood at the top of the most famous rock climb in the world. What should I feel?

Michael had that kind of total dedication that takes you to the top. Aside from one snag with our haul bags, the rest of the headwall went down without complication. Maybe Mr. Jingus was getting old too - or at least took a nap.

On the last pitch, it was night time again. The bags swung out away from me, revealing the moon in the background. It was a pretty amazing sight. By the time we both made it to the high point and the bags were up, the sun was rising. Another all-nighter. I was broken. I was so tired I could barely move. Then, Mr. Jingus stirred from his slumber, tangling the ropes one last time. I just wanted to lay down, but the climb was not over - we still had to get our bags up and over the top and we still had a descent.

While pulling up the bags, I looked down to try to see other climbers below. They were dots of color lost in the folding waves of granite. This time below us, instead of above.

We are kings.

We were quiet, taking in these last moments. With my grey wind jacket and the white ropes piled on my shoulders, I looked like some mythical sea creature with two jutting headlamps for eyes, swimming up out of some deep water. This part of the climb was over and I now stood at the top of the most famous rock climb in the world. What should I feel?

I felt, unlike the first time, that we had legitimately earned it.

I made it to the top once before, but it had felt like luck somehow - like I had barely made it, ability wise. I am a better climber now, yet more frail. This time I did not suffer irrational fear. I knew when to be cautious and when it was okay to take a fall, and I did once, on terrain many would find easy. It wasn't easy for me. I got back up and figured it out.

After several all-nighters and with Mr. Jingus breathing down by back, it felt like Michael and I could endure anything. I learned I could count on Michael completely. I found I was looking forward to getting back home and taking care of my body and the rest of my life. My marriage and family seemed more important than ever, yet I'd be a liar if some part of me wasn't laying plans for another big climb*. In this sterile society it is hard to cultivate real relationships, and, after this experience, I am confident that Michael and I will always be friends.

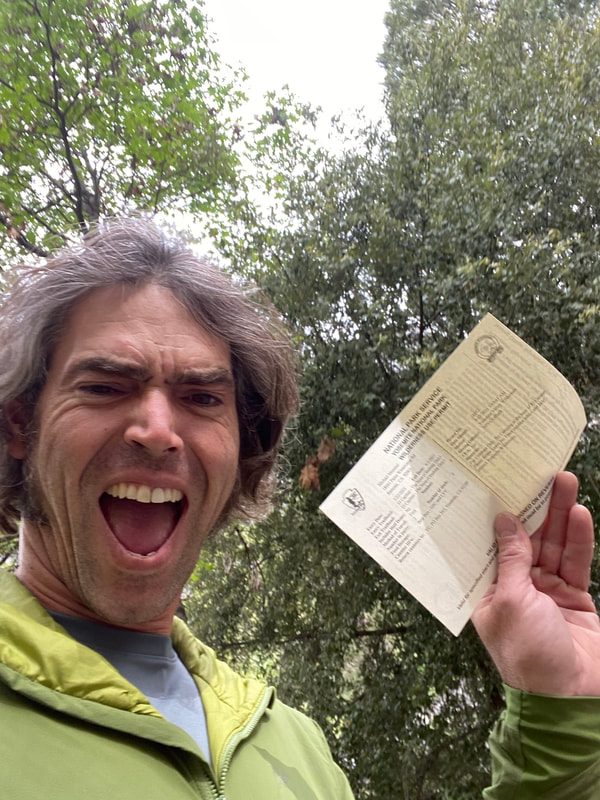

We took a summit selfie to commemorate the victory. Summit selfies are somehow always perfect, even if they are blurry.

I made it to the top once before, but it had felt like luck somehow - like I had barely made it, ability wise. I am a better climber now, yet more frail. This time I did not suffer irrational fear. I knew when to be cautious and when it was okay to take a fall, and I did once, on terrain many would find easy. It wasn't easy for me. I got back up and figured it out.

After several all-nighters and with Mr. Jingus breathing down by back, it felt like Michael and I could endure anything. I learned I could count on Michael completely. I found I was looking forward to getting back home and taking care of my body and the rest of my life. My marriage and family seemed more important than ever, yet I'd be a liar if some part of me wasn't laying plans for another big climb*. In this sterile society it is hard to cultivate real relationships, and, after this experience, I am confident that Michael and I will always be friends.

We took a summit selfie to commemorate the victory. Summit selfies are somehow always perfect, even if they are blurry.

++

Getting down off a big climb is the worst.

You are beyond tired, yet must strap on obscenely heavy loads and march. Then rappel. Then carry over loose rock. Then hike.

It was one hour past dawn when I finally was horizontal on the ground, free of the harnesses and slings. I made a quick meal of freeze-dried lasagna, ate every last drop, drank some electrolytes. Then I laid down in the blazing sun. Like it or not, I knew I was going to sleep. I covered my hands and face with a sweaty shirt so as not to burn in the sun as I slipped away. In my wild dreams, Mr. Jingus showed up - or maybe this time it was the spirit of Batso - Warren Harding - himself.

"You guys did good, man. You made it. I tried to fuck you up a couple of times, but it was all in good fun. You can go ahead and have an ice-cold victory beer when you get down there. You deserve the reward. In fact, get a whole case. She will never know."

I look away.

"Semper farcisimis?" He asks with a nudge. I laugh, recalling Warren Harding's "Sierras drinking and farcing society." Yes, indeed, nothing should be taken too seriously.

I reply, "You bet. Always."

I woke in a deep daze. Baked from the sun. Baked from the climb. Pulling my last bit of reserves to make it down. That dream clung like a haze over my brain. As I descended I realized this trip was not really about rock climbing. I simply wanted to experience what Michael and I experienced up there. We were riding a dragon on a giant stage and got so far gone physically and emotionally that I'm not sure many would be able to understand. In getting to the top, we discovered that we were made of the right kind of stuff. We completed a massive climb that sees at least 50% of those who attempt it retreat. We both know now that we can endure the pain and can call forth energy from ourselves we didn't know we had.

Getting down off a big climb is the worst.

You are beyond tired, yet must strap on obscenely heavy loads and march. Then rappel. Then carry over loose rock. Then hike.

It was one hour past dawn when I finally was horizontal on the ground, free of the harnesses and slings. I made a quick meal of freeze-dried lasagna, ate every last drop, drank some electrolytes. Then I laid down in the blazing sun. Like it or not, I knew I was going to sleep. I covered my hands and face with a sweaty shirt so as not to burn in the sun as I slipped away. In my wild dreams, Mr. Jingus showed up - or maybe this time it was the spirit of Batso - Warren Harding - himself.

"You guys did good, man. You made it. I tried to fuck you up a couple of times, but it was all in good fun. You can go ahead and have an ice-cold victory beer when you get down there. You deserve the reward. In fact, get a whole case. She will never know."

I look away.

"Semper farcisimis?" He asks with a nudge. I laugh, recalling Warren Harding's "Sierras drinking and farcing society." Yes, indeed, nothing should be taken too seriously.

I reply, "You bet. Always."

I woke in a deep daze. Baked from the sun. Baked from the climb. Pulling my last bit of reserves to make it down. That dream clung like a haze over my brain. As I descended I realized this trip was not really about rock climbing. I simply wanted to experience what Michael and I experienced up there. We were riding a dragon on a giant stage and got so far gone physically and emotionally that I'm not sure many would be able to understand. In getting to the top, we discovered that we were made of the right kind of stuff. We completed a massive climb that sees at least 50% of those who attempt it retreat. We both know now that we can endure the pain and can call forth energy from ourselves we didn't know we had.

|

Michael and I are not twenty somethings. We are grown men with families. We made the decision to throw ourselves at this hard thing while we still could. And, as we experienced, we manifested the motto of anyone who chooses to put in the hard work can reap the reward.

But, I have also realized that in order to have a perfect climb, the bills must be paid at home and the spouse and family must not only be content, but actually wanting you to return. The climb can't just be about the climb, it must always involve taking care of the other things in life - home, ourselves, and our loved ones. That realization was the biggest difference between this return to El Capitan and my first time: family is the most important thing of all. The sun was set by the time we reached the bottom. Back at the road, I left Michael at the Manure Pile Buttress and slogged to my truck in the dark. |

People were still gathered in the meadow to watch the climbers.

"You lost?" one of them asks.

I was almost incoherent - my attention divided between them and the lights high above. El Capitan never looks bigger than when you've just got off of it.

"I forget where I parked." I replied. They laughed and I walked down the road in an awkward shuffle. I realized that my truck was not responding to my key fob, so I turned and shuffled back the other direction past the same crowd. At this point I realized that the people think I'm drunk.

If only they knew.

I joked to them as I pass, "I'll figure it out!" and I walked the extra quarter-mile back to my truck. Minutes later a Park Ranger showed up and asked if I'm alright. He acted like he wanted to search me and said, "You are walking kind of funny."

I sat down in my truck and slowly removed one of my boots and socks. It was a painful process. The tops of my small toes were rubbed completely raw and blisters oozed and protruded on the tips of several toes. After seeing my feet, the ranger did not give me a field sobriety test. And, despite Mr. Jingus' mischievous prodding, there was no question in my mind that I would not be having that ice-cold beer.

"You lost?" one of them asks.

I was almost incoherent - my attention divided between them and the lights high above. El Capitan never looks bigger than when you've just got off of it.

"I forget where I parked." I replied. They laughed and I walked down the road in an awkward shuffle. I realized that my truck was not responding to my key fob, so I turned and shuffled back the other direction past the same crowd. At this point I realized that the people think I'm drunk.

If only they knew.

I joked to them as I pass, "I'll figure it out!" and I walked the extra quarter-mile back to my truck. Minutes later a Park Ranger showed up and asked if I'm alright. He acted like he wanted to search me and said, "You are walking kind of funny."

I sat down in my truck and slowly removed one of my boots and socks. It was a painful process. The tops of my small toes were rubbed completely raw and blisters oozed and protruded on the tips of several toes. After seeing my feet, the ranger did not give me a field sobriety test. And, despite Mr. Jingus' mischievous prodding, there was no question in my mind that I would not be having that ice-cold beer.

*I'd love to finish my climbing on the Zodiac and if possible I want to do it solo. That will be a hell of a story: an old man alone up there.

Big Wall Climbing 201

Not big wall theory: Big wall fact

- "If it's not clipped in, it's gone." Items we dropped included a pulley. A large rope bucket. A small wall bag. A days supply of food. A package of trail mix. One brass stopper. One nut tool. One carabiner. My haul bag docking chord.

- If it's critical, take two. We destroyed one complete hauling system.

- You have two choices on The Nose: fast and light or heavy and slow. Those taking about four days were cruising most of the 5.10 free climbing. Those climbing NIAD (Nose in a day) are 5.11+ free climbers and usually have done the route six or more times.

- You will fail if you do not bring enough water, and other parties WILL slow you down unless you are flying by them. Two gallons per person per day is realistic consumption. Every team we saw bail bailed because of water running low.