|

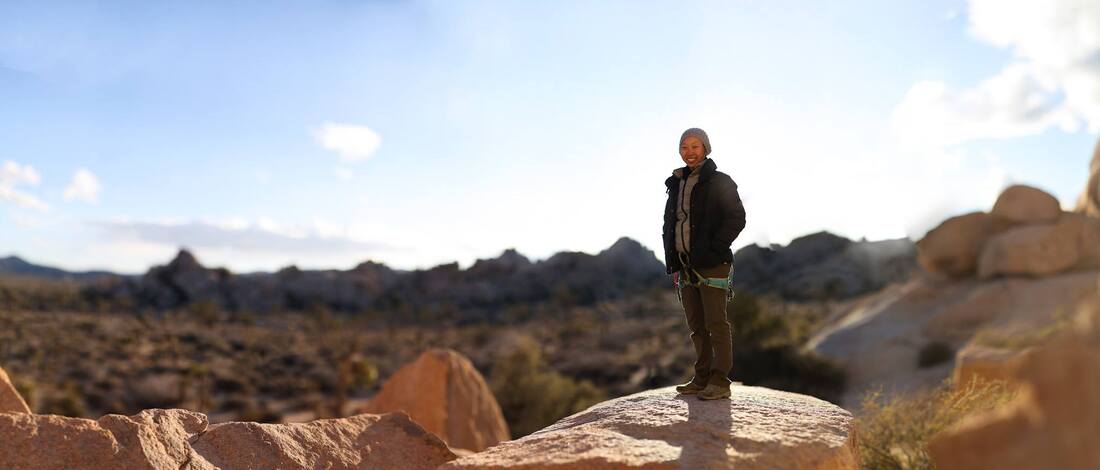

I’m lucky to be here. To own a business that expresses both my creativity and love of climbing is one of the greatest joys I have experienced - though it has also come with its fair share of obstacles. What I value most about my work is learning to apply myself in every way - learning more every day. The icing on this already sweet cake is being a part of a community of brilliant individuals that bring me joy.

When reflect upon how I arrived at this place - becoming a full-time business owner - I realize I cannot separate my history from my present. Not only my history - the one of this particular body - but the one that extends long before that. My extended history is fraught with many questions, long periods of pain peppered with moments of joy. Many generations have been covered with a thick and heavy mist of unresolved sadness. This inherited, generational weight permeates everything I do. This feeling of gravity is what I believe to be my Korean-Americanness. It is what serves as a constant reminder of my ancestors. I will attempt to tell a story about how I came to be here. Some parts of it are pieced together from rumors heard through the walls while “the adults” were talking. Other parts are pieced together from insinuation and vague stories. Sometimes, this painful past is simply too much for my family to recall. They have either blocked out events from their memories or simply do not speak of it. I believe they have kept it from me so as to not burden me with carrying the load. However, the weight is with me whether or not I am aware of the details. My parents met at a Korean church in Los Angeles during the late 70’s. |

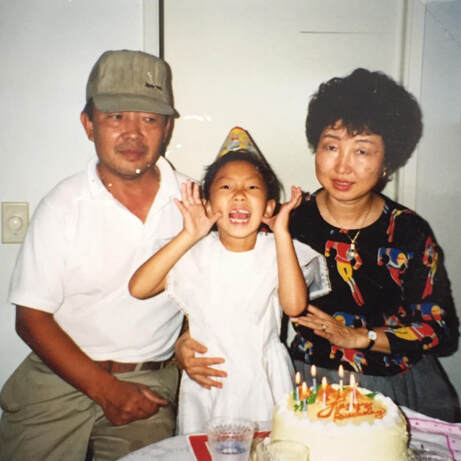

My mother and father didn’t know much about each other, but figured they might as well get married since they went to the same church, they were both single, and aging out of their prime. I don’t know much about my father, just that he may have come from a small island off the southern tip of South Korea. I grew up in the same home as my father, my mother, my mother’s mother, and my grandmother’s mother. It was a matriarchy, four generations of women living together and holding all the power. To be honest, my father had little place there, but he stuck around.

The women in my family are from a country that is no longer - North Korea before it was called “North.” It is a country that now exists only in memory. I believe this memory is what my mother still refers to as “home,” though she has lived here in the United States for far longer than she was ever there. I hear the northern parts of Korea are - or at least were - beautiful, mountainous, and with so many trees.

My family lived in a rural home with a well on the property. Access to fresh water was something of which my family was immensely proud. They grew or foraged much of their own food and meat was a rare treat. They used a wood stove to heat the home in the winter, and took joy in eating cabbage stems when there was nothing else.

Then something happened, politically and historically. Power changed hands, and circumstances changed for the people. In 1910, the Japanese Empire annexed Korea without consent from the Korean people. Though a treaty was signed, there are many questions about the conditions under which it was signed. Koreans were seen by the new rulers as backwards people who needed reform and assimilation. Men were sent away and forced into labor, and many women were taken from their homes to be “comfort women,” a form of sexual slavery.

My grandmother has two names. In Korean, her name is Kyung-Ja. In Japanese, Keiko (“Happy child.”) I knew the name Keiko had something to do with the occupation, but I never asked for the details. Upon doing my own research, I learned that “Koreans who retained their Korean names were not allowed to enroll at school, were refused service at government offices, and were excluded from the lists for food rations and other supplies.”

|

From our family stories, I’ve learned that Koreans were not allowed to speak their native tongue, and would be brutally punished for expressing any Korean-ness or rebelling against the Japanese. Authorities were all to be feared, and acting out of line would almost certainly result in brutality or death. Christianity became a form of rebellion against the oppressor’s Shinto religion.

The women in my family are fervently religious. I always thought this to be foolish, but I now understand the significance it had in preserving their identity. My grandmother, Kyung-Ja, who took the Japanese name Keiko, and later the American name, Prisca, had one child. She was 19 when she gave birth to my mother, Heekyung. I believe she may have wanted more children, but according to our family’s story, my grandfather was killed when my mother was just a baby. My mother never knew her father and my grandmother never dated, remarried, or had children again. |

Political power begins to change hands again, this time out of the Japanese and into either Soviet or American hands. Kyung-Ja and her three sisters, along with their families, decided to make the pilgrimage from the northern part of the Korean peninsula to the south. Perhaps they knew the country would be split in two, so they packed up their belongings to get to the American side before the split was solidified.

They hired a “tour guide” to get across the border in the face of an oncoming war. To my knowledge, "tour guides" were often questionable characters who were paid to get families out of North Korea. This experience is one of the hardest things for my mother to talk about. She chokes up whenever she tells me about this journey, and we usually do not have extended discussions about it.

As soon as our family crossed the border, the tour guide robbed the group of every box, bag, and bundle, leaving each family member only with what they were wearing. If my family bears a great fear of material loss, I believe this is where it originates from.

My grandmother is now ninety-four and has severe dementia. That also means she’s lost much of her ability to filter her words. A few years ago, she thanked my mother for not crying on a certain boat. She didn’t want to have to drown her only child for making noise on a ship where refugees were not allowed to be found. What is true and what is legend is still unclear to me, as many of the stories of the Korean diaspora remain untold. But we are losing the people who experienced them, and these holes in our histories sit with us like a ghost.

It is my mother's belief that a tub of water was often placed in areas where small children were kept. If one cried out, they were immediately drowned to save the rest of the group from being found. Somehow, my lineage survived.

Heekyung, my mother, is the smart one. My grandmother, Kyung-Ja, is a schoolteacher, and along with her sisters, raised Heekyung to be the smartest child they could possibly rear. Even as a child from a poor rural area, she excelled in school and got accepted on a scholarship to the most elite high school in all of South Korea. It was so elite that in her seventies, she still travels to alumni events around the world. When my mom entered the school, she lacked the social and cultural savvy of the big cities in the South. She never really figured out how to fit in. She was however, my family’s ticket out of poverty, so there was no letting up on the studies.

Ever since my family’s life’s possessions were stolen, every family member took up knitting. They knitted socks for soldiers in order to have money to eat. Their ultimate goal was to get to the United States, where they believed my mother, with her smarts, could have a high paying job and they could live with less struggle.

As soon as our family crossed the border, the tour guide robbed the group of every box, bag, and bundle, leaving each family member only with what they were wearing. If my family bears a great fear of material loss, I believe this is where it originates from.

My grandmother is now ninety-four and has severe dementia. That also means she’s lost much of her ability to filter her words. A few years ago, she thanked my mother for not crying on a certain boat. She didn’t want to have to drown her only child for making noise on a ship where refugees were not allowed to be found. What is true and what is legend is still unclear to me, as many of the stories of the Korean diaspora remain untold. But we are losing the people who experienced them, and these holes in our histories sit with us like a ghost.

It is my mother's belief that a tub of water was often placed in areas where small children were kept. If one cried out, they were immediately drowned to save the rest of the group from being found. Somehow, my lineage survived.

Heekyung, my mother, is the smart one. My grandmother, Kyung-Ja, is a schoolteacher, and along with her sisters, raised Heekyung to be the smartest child they could possibly rear. Even as a child from a poor rural area, she excelled in school and got accepted on a scholarship to the most elite high school in all of South Korea. It was so elite that in her seventies, she still travels to alumni events around the world. When my mom entered the school, she lacked the social and cultural savvy of the big cities in the South. She never really figured out how to fit in. She was however, my family’s ticket out of poverty, so there was no letting up on the studies.

Ever since my family’s life’s possessions were stolen, every family member took up knitting. They knitted socks for soldiers in order to have money to eat. Their ultimate goal was to get to the United States, where they believed my mother, with her smarts, could have a high paying job and they could live with less struggle.

|

In the 1970’s, my grandmother and my mother made it to Los Angeles. My grandmother had a friend who was willing to put them up until they got their feet on the ground, so they graciously lived on floors or guest bedrooms while looking for work. My grandmother got a job at the Xerox factory, assembling computer chips. From educator to factory line worker was quite the switch. My grandmother didn’t know how to speak English at all. She dressed in handmade clothing and was teased and bullied by Americans of every kind. Eventually, my mother graduated from California State University, Los Angeles with a chemistry degree and began working for Kaiser Permanente.

My mom had purchased her dream house in Manhattan Beach early in her career. My grandmother and my great-grandmother lived there, with their unbreakable bond of a shared traumatic journey. When my father came onto the scene, he brought violence and alcoholism, and he was unable to hold a job. My mom sold her home to feed my father’s shoddily-planned and thus-failed business ideas. Yet, my mother’s dream was to have a family. They had been trying for over five years to have a child. Finally, with the help of doctors and fertility treatments, pregnancy happens. |

Then what?

Severe postpartum.

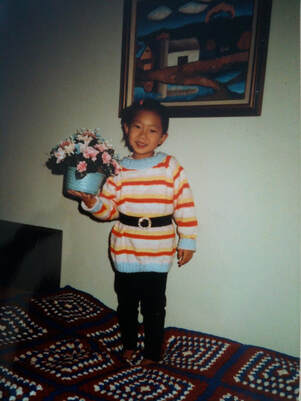

The postpartum, the alcoholic father, the violence, the historic trauma poured into me. It manifested, even as an infant, as an unreasonable fear of all people. I chose not to speak in public, instead, immersing myself in crafts or writing. My school teachers were perplexed at why I knew the answers to questions, but refused to raise my hand. They saw it as defiance and gave me poor grades in “class participation.”

My mother, perhaps because it had been done to her, saw my academic potential, pushing me to excel in math and science - I went to the Math Olympics. I learned to play classical piano and the violin. What I am best at is what I was not allowed to have a career in - art, writing, social sciences.

I made it through half of a biology undergraduate degree and, after many turns of events, I break.

I’ll call the official date of my break on February 9, 2012. I recall this event like high-siding off a motorcycle at full speed when something has caused you to hit the brakes too hard. (I used to ride back then, so this is the most vivid analogy for me.) By that time, I had lived without addressing much of my history. I hung out with a bad crowd. I had gotten engaged twice, had been in an emotionally abusive relationship for five years, and whatever joy or freedom I may have felt as a child was simply gone. I drank and got into drugs and cared very poorly for myself.

My journey from then until now is one that I truly never thought possible. If I told myself in 2012 that in eight years I would become a clear-headed, happy individual who climbs and owns a fulfilling creative business that helps others, I would have laughed. Or cried. I don’t know. I just wouldn’t have believed it.

When I broke down, I had just come out of an emotionally abusive relationship that had lasted five years. During that relationship, I grew numb to the constant insults to my character and began to think it was normal. I was unable to respond coherently to questions asked about how my days were going. When I was asked to do any kind of critical thinking combined with emotional processing, my mind simply wouldn’t let me process. I felt stupid, and acted stupid, too. I felt as though I was tearing out my hair, trying to access a part of myself that I knew existed but couldn’t express. It wasn’t until much later that I learned about abuse and trauma, and its profound effects on how we think and behave.

For about a year, I was having panic attacks multiple times a day. My emotions would swing wildly and my face and back would burn with an internal heat that made me feel as though I was on fire. I began to feel things at all the wrong times, and found myself being deemed socially inappropriate. I wanted to share my experience with others, but very few would listen, and those who did couldn’t relate. I didn’t understand PTSD at the time, but I’m sure that if I had educated myself about it, I would have found some solace.

I’ve always used art and writing as a way to process my emotions and see them more objectively. During this time, I began to write incessantly, even waking up from dreams to write down what I was feeling. I came to a point where I understood that if I did not express what was in the many notebooks in my bedroom, I was at a very high risk of being unhappy for the rest of my life, and possibly even ending my own life.

With no formal training in fine art, I began to make paintings and apply to local group art walks. During my first exhibition, I was too afraid to be in the same room with my art, so I would load up on cheap gallery wine and hang out with the street painters or wander around the other galleries. With each art show, I became better at my craft and better at processing my thoughts and feelings.

When I started rock climbing, I knew there was something about climbing that I wanted to express, but I didn’t exist yet in climbing-inspired art. Climbing connects me to my body. Nature connects me to my place in the world. Art allows me to express how a variety of connections interact with each other, and is my way of expressing and processing my own feelings about the subject. In creating art about human interaction with the natural world, I feel as though I’ve finally stopped tearing my hair out about the things I couldn’t express. It became a way out from feeling lonely, misunderstood, and damaged.

Severe postpartum.

The postpartum, the alcoholic father, the violence, the historic trauma poured into me. It manifested, even as an infant, as an unreasonable fear of all people. I chose not to speak in public, instead, immersing myself in crafts or writing. My school teachers were perplexed at why I knew the answers to questions, but refused to raise my hand. They saw it as defiance and gave me poor grades in “class participation.”

My mother, perhaps because it had been done to her, saw my academic potential, pushing me to excel in math and science - I went to the Math Olympics. I learned to play classical piano and the violin. What I am best at is what I was not allowed to have a career in - art, writing, social sciences.

I made it through half of a biology undergraduate degree and, after many turns of events, I break.

I’ll call the official date of my break on February 9, 2012. I recall this event like high-siding off a motorcycle at full speed when something has caused you to hit the brakes too hard. (I used to ride back then, so this is the most vivid analogy for me.) By that time, I had lived without addressing much of my history. I hung out with a bad crowd. I had gotten engaged twice, had been in an emotionally abusive relationship for five years, and whatever joy or freedom I may have felt as a child was simply gone. I drank and got into drugs and cared very poorly for myself.

My journey from then until now is one that I truly never thought possible. If I told myself in 2012 that in eight years I would become a clear-headed, happy individual who climbs and owns a fulfilling creative business that helps others, I would have laughed. Or cried. I don’t know. I just wouldn’t have believed it.

When I broke down, I had just come out of an emotionally abusive relationship that had lasted five years. During that relationship, I grew numb to the constant insults to my character and began to think it was normal. I was unable to respond coherently to questions asked about how my days were going. When I was asked to do any kind of critical thinking combined with emotional processing, my mind simply wouldn’t let me process. I felt stupid, and acted stupid, too. I felt as though I was tearing out my hair, trying to access a part of myself that I knew existed but couldn’t express. It wasn’t until much later that I learned about abuse and trauma, and its profound effects on how we think and behave.

For about a year, I was having panic attacks multiple times a day. My emotions would swing wildly and my face and back would burn with an internal heat that made me feel as though I was on fire. I began to feel things at all the wrong times, and found myself being deemed socially inappropriate. I wanted to share my experience with others, but very few would listen, and those who did couldn’t relate. I didn’t understand PTSD at the time, but I’m sure that if I had educated myself about it, I would have found some solace.

I’ve always used art and writing as a way to process my emotions and see them more objectively. During this time, I began to write incessantly, even waking up from dreams to write down what I was feeling. I came to a point where I understood that if I did not express what was in the many notebooks in my bedroom, I was at a very high risk of being unhappy for the rest of my life, and possibly even ending my own life.

With no formal training in fine art, I began to make paintings and apply to local group art walks. During my first exhibition, I was too afraid to be in the same room with my art, so I would load up on cheap gallery wine and hang out with the street painters or wander around the other galleries. With each art show, I became better at my craft and better at processing my thoughts and feelings.

When I started rock climbing, I knew there was something about climbing that I wanted to express, but I didn’t exist yet in climbing-inspired art. Climbing connects me to my body. Nature connects me to my place in the world. Art allows me to express how a variety of connections interact with each other, and is my way of expressing and processing my own feelings about the subject. In creating art about human interaction with the natural world, I feel as though I’ve finally stopped tearing my hair out about the things I couldn’t express. It became a way out from feeling lonely, misunderstood, and damaged.

|

One aspect of race, history, and identity is that it is inescapable. Every experience I’ve had, and every decision I’ve made is a product of my Asian-Americanness.

The traumas that my lineage has endured, and the effects of leaving them unresolved, has informed too many of the decisions I am least proud of. When I started to honor myself, learn more about my ancestors, and connect with my history, I began to find an independence I didn’t know I could have. I wasn’t bound to just reacting to the many impulses that were programmed in my habits. Honoring and celebrating my Asian-American heritage, for me, is not about going out to eat Korean BBQ with my Korean friends, or being aware of whatever trends coming are out of Korea (though partaking in that culture from time to time can be fun.) To honor my heritage is to know my self-worth, to respect the cost at which I came to be here, and to be as kind and fair as I can to those around me. My inheritance may be covered in a fog of heavy sadness, but there is a reward in finding my way through it. Underneath that fog is an unbreakable resilience and the ability to find scraps of joy even during terrible times. This is what I hold most dearly about my heritage, and to live my life in a way that makes use of what has been handed down to me is the greatest honor I can give to those who came before me. |