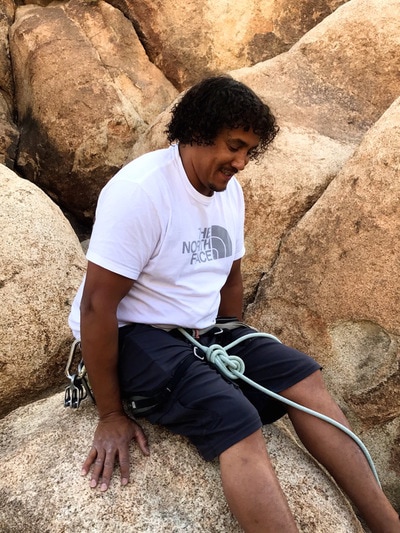

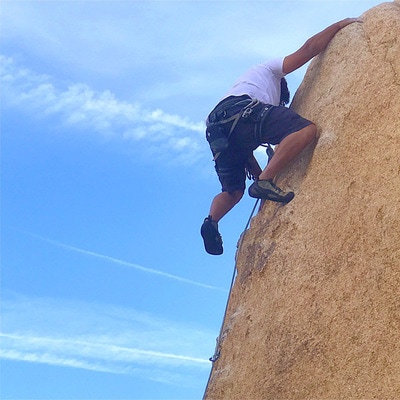

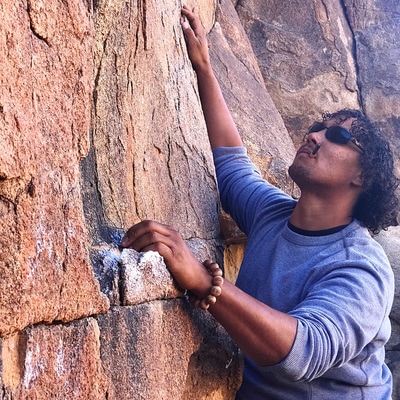

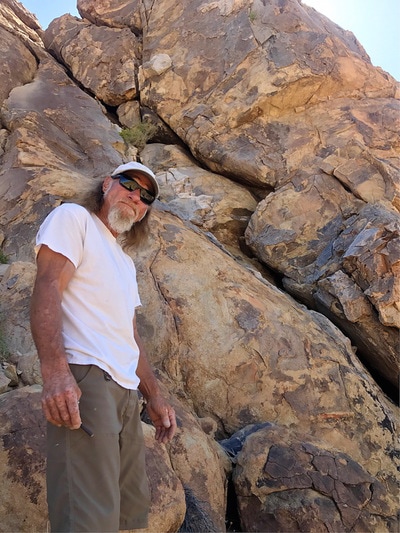

Farai Muchenje is a more recent addition to the climbing world. Kelly Vaught is a stone master, having emerged into the world of climbing and first ascents in the heyday of Idllywild and Camp 4 in Yosemite. Together, they are a team of Joshua Tree “new-school” route developers.

For some, using the words “new-school,” “route development”, and “Joshua Tree” all in the same sentence can be hair-raising/red-flag inducing/trouble-making. For others it elicits great relief and gratitude.

What exactly does “new school” mean in JTree? It’s a hint of today’s bolting ethics mixed with local JTree flavor. To better understand, we need to dig a bit deeper into JTree.

JOSHUA TREE’S BOLTING HISTORY

Joshua Tree is known for it’s surreal beauty, cartoonish blobs of granite, sand-bagged old-school ratings, and run-out. Common characteristics of the rock are barely there discontinuous cracks that meet featureless domes of slab. Are those bulbous domes climbable? Sure. Are they protectable? Not without bolts. So what was a climber to do in the days of yore? Essentially, free solo those sections.

When bolts first emerged as a form of climbing protection the holes had to be hand drilled, often while on lead. Imagine for a moment: You are on steep featureless slab, very little, if any protection is placed below you, your feet hang tenuously onto the rock. Then you let go with your hands, grab a hand-cranked drill, and slowly begin drilling. When the hole is done you hammer in the bolt and secure the hanger. How many bolts would you want to place if your other option was to haul ass up the slab to relative safety? Hence there are very few bolts.

Hand drilling on lead is one of the early, practical, reasons run-out exists in Joshua Tree. But, even as battery powered drills came into existence, perceptions and ethics were shaped by the minimal bolting. There was the early leave-no-trace ethic of do not mar the rock. Or the bad-ass ethic of if you can’t do it without protection you should not be climbing it. Or, even the default ethic of that is the way its always been done. All of these perceptions resulted in run-out.

Fast forward to today, where the popularity of sport climbing exceeds that of traditional climbing. Although it took some time to be accepted, placing bolts in rock is now par for the course – in most places, that is. Joshua Tree is one of the last major hold-outs for minimal bolting.

Bolt-chopping wars still occur here. This is in part because of remnants of historical beliefs, but it is also a manifestation of people believing in adhering to the National Park requirements. The bolting allowances in the park are a little complicated but they are:

To complicate matters, although the park was established in 1936, the wilderness-designated areas continue to expand within the park. For example, in 1990, 163,800 acres was designated as wilderness. Then, in 2009 an additional 37,000 acres was given the wilderness designation. When an area transitions into wilderness, the routes that already existed in the area are grandfathered in. However, any new route development must follow the rules described above.

Since not every route in Joshua Tree has been documented, it is difficult to know what is comparatively “new” or “old.” Due to the historical frowning-upon of bolting, there are plenty of “unclaimed” bolted routes scattered in the park. For these routes there is no known history of first ascents, the year established, and the original number of bolts.

Park Officials, who are tasked with enforcing the rules, are faced with questions like, was that route bolted prior to the 1990 California Desert Protection Act or the 2009 Omnibus Public Lands Management Act, or even the 1976 act that established over 80% of the park as wilderness? Who knows.

CONUNDRUM: THE DESIRE TO BOLT AND PRESSURE NOT TO

Enter today’s JTree route developers. Here they are, surrounded by 1200 square miles of drool-inducing rock, and a huge fraction of it is essentially “off limits,” at least to bolting.

Sure, there are plenty of trad-only first ascents to be had, but some of those lines are crazy deep in the park, or have no descent other than to rappel. What do you do if you can’t get off the rock? One might suggest to sling a natural feature and rap, but leaving slings is also not allowed in Joshua Tree wilderness (in fact, if you think about it, bolted anchors are less visually obstructive than slings and do not deteriorate into colorful, useless trash after a year in the UV radiation). Conundrum.

In addition to the trad lines, there are also so many aesthetically pleasing unprotectable face-climbs. From a climber’s perspective it can be painful to walk by and see such a beautiful line go unsent. Since most people don’t want to free solo and, unfortunately, top rope options are few and far between, the only option to free that line is to bolt. Double conundrum.

But, bolting is not just about freeing a new line; it’s also about safety and accessibility. Bolting has aligned with shifts in world views, moving from one of purity and dangerous adventure, to reducing unnecessary danger and making the beautiful world accessible to all. Triple conundrum.

Thus, there is also a shift in the perspectives of today’s route developers, where they value placing permanent protection. This is true for even the original developers who were previously quite vocal against placing bolts.

So what is a new route developer to do in someplace like Joshua Tree?

BACK TO FARAI AND KELLY

Unless you are establishing trad-only lines in Joshua Tree (which Farai and Kelly are doing), route developers regularly face these difficult conundrums. Farai and Kelly are navigating this space carefully by scoping out new crags in non-wilderness areas (which, by the way, are nice and close to the roads!) and finding locations where they can do some trad first ascents and then rappel into face climbs.

Rap-bolting was once (and for some still is) frowned upon, but rappelling makes it much easier to hand-drill, thereby meeting park requirements if you don’t have a powered drill permit. Rap-bolting also allows the developer to practice the climb and locate ideal bolt placement, thus protecting for cruxes and ground-fall, but also strategically minimizing bolts (this also includes not placing bolts where a route is protectable using trad gear). Lastly, bolts are minimized by having shared anchors for multiple routes.

Farai and Kelly are excited about their work, but they, like many are caught up in the JTree conundrum - excited by “modern” route development, but also understanding the need for and perspectives of preservation.

It’s a really tough struggle that many people in the Joshua Tree community are navigating. Organizations like Friends of Joshua Tree and Access Fund are acting as liaisons between Park Officials and the climbing community. Everyone is looking for balance, but it’s a tough act, especially as the popularity of climbing using bolts grows. The pressure to bolt is really only going to increase.

For now, though, sticking to developing routes in the non-wilderness corridors seems like a good solution. In fact, perhaps it's a win-win. For one, the approaches to these areas are much shorter, making it easier for climbers. Second, it reduces the footprint in the wilderness.

HIghlighted Crags:

Joshua Tree Wilderness Boundaries Map

For some, using the words “new-school,” “route development”, and “Joshua Tree” all in the same sentence can be hair-raising/red-flag inducing/trouble-making. For others it elicits great relief and gratitude.

What exactly does “new school” mean in JTree? It’s a hint of today’s bolting ethics mixed with local JTree flavor. To better understand, we need to dig a bit deeper into JTree.

JOSHUA TREE’S BOLTING HISTORY

Joshua Tree is known for it’s surreal beauty, cartoonish blobs of granite, sand-bagged old-school ratings, and run-out. Common characteristics of the rock are barely there discontinuous cracks that meet featureless domes of slab. Are those bulbous domes climbable? Sure. Are they protectable? Not without bolts. So what was a climber to do in the days of yore? Essentially, free solo those sections.

When bolts first emerged as a form of climbing protection the holes had to be hand drilled, often while on lead. Imagine for a moment: You are on steep featureless slab, very little, if any protection is placed below you, your feet hang tenuously onto the rock. Then you let go with your hands, grab a hand-cranked drill, and slowly begin drilling. When the hole is done you hammer in the bolt and secure the hanger. How many bolts would you want to place if your other option was to haul ass up the slab to relative safety? Hence there are very few bolts.

Hand drilling on lead is one of the early, practical, reasons run-out exists in Joshua Tree. But, even as battery powered drills came into existence, perceptions and ethics were shaped by the minimal bolting. There was the early leave-no-trace ethic of do not mar the rock. Or the bad-ass ethic of if you can’t do it without protection you should not be climbing it. Or, even the default ethic of that is the way its always been done. All of these perceptions resulted in run-out.

Fast forward to today, where the popularity of sport climbing exceeds that of traditional climbing. Although it took some time to be accepted, placing bolts in rock is now par for the course – in most places, that is. Joshua Tree is one of the last major hold-outs for minimal bolting.

Bolt-chopping wars still occur here. This is in part because of remnants of historical beliefs, but it is also a manifestation of people believing in adhering to the National Park requirements. The bolting allowances in the park are a little complicated but they are:

- In non-wilderness areas bolts can be placed using a hand drill. Power drills require a permit.

- In wilderness areas a permit is required to place any new bolts – even if using a hand drill. Old bolts can be replaced bolt-for-bolt. [For reference, over 75% of the park is designated wilderness (some documents say 85 or 90%)].

- There are a few areas that are labeled “anchor free zones.” Where no bolts are allowed in order to maintain the natural aesthetic of the environment.

- It takes about 6 months for a bolting permit to get approved. (Which some perceive as unrealistic to accommodate the demand.)

To complicate matters, although the park was established in 1936, the wilderness-designated areas continue to expand within the park. For example, in 1990, 163,800 acres was designated as wilderness. Then, in 2009 an additional 37,000 acres was given the wilderness designation. When an area transitions into wilderness, the routes that already existed in the area are grandfathered in. However, any new route development must follow the rules described above.

Since not every route in Joshua Tree has been documented, it is difficult to know what is comparatively “new” or “old.” Due to the historical frowning-upon of bolting, there are plenty of “unclaimed” bolted routes scattered in the park. For these routes there is no known history of first ascents, the year established, and the original number of bolts.

Park Officials, who are tasked with enforcing the rules, are faced with questions like, was that route bolted prior to the 1990 California Desert Protection Act or the 2009 Omnibus Public Lands Management Act, or even the 1976 act that established over 80% of the park as wilderness? Who knows.

CONUNDRUM: THE DESIRE TO BOLT AND PRESSURE NOT TO

Enter today’s JTree route developers. Here they are, surrounded by 1200 square miles of drool-inducing rock, and a huge fraction of it is essentially “off limits,” at least to bolting.

Sure, there are plenty of trad-only first ascents to be had, but some of those lines are crazy deep in the park, or have no descent other than to rappel. What do you do if you can’t get off the rock? One might suggest to sling a natural feature and rap, but leaving slings is also not allowed in Joshua Tree wilderness (in fact, if you think about it, bolted anchors are less visually obstructive than slings and do not deteriorate into colorful, useless trash after a year in the UV radiation). Conundrum.

In addition to the trad lines, there are also so many aesthetically pleasing unprotectable face-climbs. From a climber’s perspective it can be painful to walk by and see such a beautiful line go unsent. Since most people don’t want to free solo and, unfortunately, top rope options are few and far between, the only option to free that line is to bolt. Double conundrum.

But, bolting is not just about freeing a new line; it’s also about safety and accessibility. Bolting has aligned with shifts in world views, moving from one of purity and dangerous adventure, to reducing unnecessary danger and making the beautiful world accessible to all. Triple conundrum.

Thus, there is also a shift in the perspectives of today’s route developers, where they value placing permanent protection. This is true for even the original developers who were previously quite vocal against placing bolts.

So what is a new route developer to do in someplace like Joshua Tree?

BACK TO FARAI AND KELLY

Unless you are establishing trad-only lines in Joshua Tree (which Farai and Kelly are doing), route developers regularly face these difficult conundrums. Farai and Kelly are navigating this space carefully by scoping out new crags in non-wilderness areas (which, by the way, are nice and close to the roads!) and finding locations where they can do some trad first ascents and then rappel into face climbs.

Rap-bolting was once (and for some still is) frowned upon, but rappelling makes it much easier to hand-drill, thereby meeting park requirements if you don’t have a powered drill permit. Rap-bolting also allows the developer to practice the climb and locate ideal bolt placement, thus protecting for cruxes and ground-fall, but also strategically minimizing bolts (this also includes not placing bolts where a route is protectable using trad gear). Lastly, bolts are minimized by having shared anchors for multiple routes.

Farai and Kelly are excited about their work, but they, like many are caught up in the JTree conundrum - excited by “modern” route development, but also understanding the need for and perspectives of preservation.

It’s a really tough struggle that many people in the Joshua Tree community are navigating. Organizations like Friends of Joshua Tree and Access Fund are acting as liaisons between Park Officials and the climbing community. Everyone is looking for balance, but it’s a tough act, especially as the popularity of climbing using bolts grows. The pressure to bolt is really only going to increase.

For now, though, sticking to developing routes in the non-wilderness corridors seems like a good solution. In fact, perhaps it's a win-win. For one, the approaches to these areas are much shorter, making it easier for climbers. Second, it reduces the footprint in the wilderness.

HIghlighted Crags:

Joshua Tree Wilderness Boundaries Map