“I was trying to get on to Echo Crack…”, read a message from Zac. I did a double take.

“Either tomorrow or next weekend," read the next one.

And so it began. “Tomorrow” and next weekend, and the weekend after and…

Let’s take it all the way back to a freezing yet sun-kissed day last August, when Zac and I rounded Horne Point for my first visit to Mt. Piddington, an iconic wall in the Blue Mountains (aka. Blueys) of Australia. Zac had his sights on climbing Janicepts, while I had mine on learning to jam. To our mutual disappointment, neither of these goals came within a stick-clip’s length of getting started, and so we both left hoping that our next adventure would be more fruitful. Enter Echo - a four-pitch trad climb with descriptors like “chossy”, “this section is almost always wet” and “the last pitch is just as hard as the others”. Although first climbed by John Ewbank and John Davis in 1968, it remained a formidable aid line until freed by Garth Miller and Gilbert Meunier in 1995.

“Either tomorrow or next weekend," read the next one.

And so it began. “Tomorrow” and next weekend, and the weekend after and…

Let’s take it all the way back to a freezing yet sun-kissed day last August, when Zac and I rounded Horne Point for my first visit to Mt. Piddington, an iconic wall in the Blue Mountains (aka. Blueys) of Australia. Zac had his sights on climbing Janicepts, while I had mine on learning to jam. To our mutual disappointment, neither of these goals came within a stick-clip’s length of getting started, and so we both left hoping that our next adventure would be more fruitful. Enter Echo - a four-pitch trad climb with descriptors like “chossy”, “this section is almost always wet” and “the last pitch is just as hard as the others”. Although first climbed by John Ewbank and John Davis in 1968, it remained a formidable aid line until freed by Garth Miller and Gilbert Meunier in 1995.

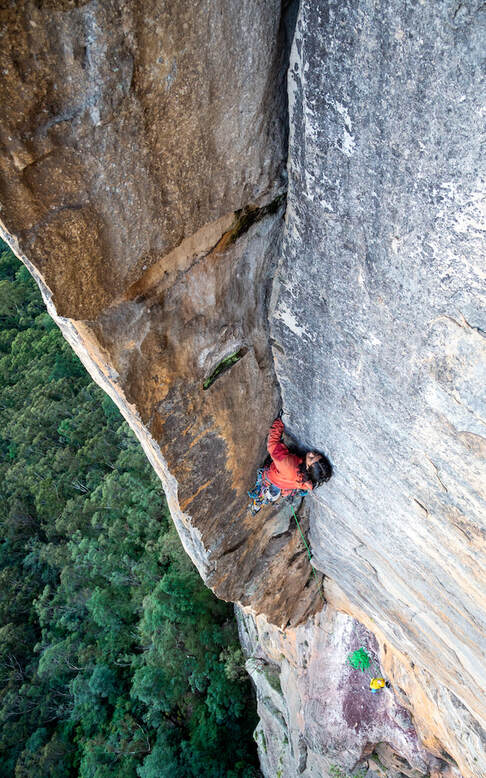

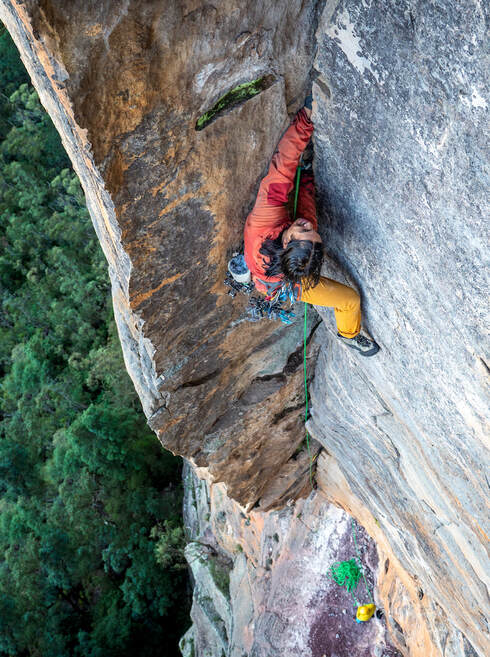

Click to enlarge the above photos: Zac (climbing) and Gavin (belaying) on Echo Crack (Photo Credit: Anton Korsun)

You can take Zac out of Squamish, but you can’t take…

The modern culture of Blueys climbing seems synonymous with hard sport, but those who look beyond the bolts are timelessly rewarded with traditional classics like Echo Crack. On the approach we navigated what felt like a post-apocalyptic jungle of street signs, flux capacitors, wheelie bins, and industrial machinery that landed below Australia’s favourite “chuck things off the cliff” spot. We were both beaming with the kind of excitement reserved for doing things you probably shouldn’t be doing.

Being the safety-conscious climbers that we are (would those who know us please play along here…), Zac and I took utmost care in assembling our humble army of ten #3 cams. Yet despite Captain Canada’s crack skills, our lack of #1’s and #2’s became apparent all too quickly on pitch three. Walking his last red cam well into Type II fun territory, Zac graced the crack with some lively lexicon which, while not fit for press, roughly translates from Canadian as “it may be worthwhile bringing triples (or quadruples) of red in lieu of some of those #3’s”. Although we finished the climb, we knew we weren't finished with the climb. Despite the abundance of perfectly good sport crags nearby, Zac was set on picking the most logistically miserable line in the Mountains to project, so we decided on the following Saturday to return for the clean send.

Being the safety-conscious climbers that we are (would those who know us please play along here…), Zac and I took utmost care in assembling our humble army of ten #3 cams. Yet despite Captain Canada’s crack skills, our lack of #1’s and #2’s became apparent all too quickly on pitch three. Walking his last red cam well into Type II fun territory, Zac graced the crack with some lively lexicon which, while not fit for press, roughly translates from Canadian as “it may be worthwhile bringing triples (or quadruples) of red in lieu of some of those #3’s”. Although we finished the climb, we knew we weren't finished with the climb. Despite the abundance of perfectly good sport crags nearby, Zac was set on picking the most logistically miserable line in the Mountains to project, so we decided on the following Saturday to return for the clean send.

What goes up, must come down

The Blueys are unique in that, unlike most mountains, these go down rather than up. Let me explain. Maybe it's easiest to think of the Blue Mountains as canyons with flat tops. All of the towns and roads sit on top, and the climbs flow down the sides. This has made the locals Olympic contenders not just in climbing, but also in steep approaches and rappelling (wink wink, IOC… I will totally fly to Paris to watch Olympic rappelling).

After going ground-up the first time, there was some discussion (or maybe excuses?) of “getting tired from the approach.” Zac needed the energy to tackle those upper pitches, so we decided to team up with trip-report guru Nikhilesh (why am I the one writing this?) and rap down for them. Training for Olympic rappelling after all. To this day no-one is quite sure why we didn’t just rap the crack. But having decided that traversing to the anchors of a nearby climb would give Nik and Zac a better chance of hitting the pitch three ledge, we boldly traversed across the void and began our descent…

For a moment, nothing happened. Then, after a few hours of patiently waiting… nothing continued to happen! Our ropes missed the ledge by about as far as you can throw a pink tricam, and I settled into a long hanging stance, strangely comforted by the fact that I still possessed our haul bag full of food. We were spread out over the wall, with me at the anchors, 10 meters away from terra firma, and my partners in climb hanging well out in space, 50 meters (160 feet) from each other. As it does (at the worst times, might I add), the sun got pretty bored with our confusion and flew away to illuminate Yosemite, leaving Zac to rap once more to the ground and escape around the Three Sisters in rock shoes. When Nik jugged up, I mumbled some excuse about my camera and put him on belay for the final 10-meter traverse. Since Zac had taken both the rack and lead line, our only dilemma became which of our two static ropes looked best to lead this.

After going ground-up the first time, there was some discussion (or maybe excuses?) of “getting tired from the approach.” Zac needed the energy to tackle those upper pitches, so we decided to team up with trip-report guru Nikhilesh (why am I the one writing this?) and rap down for them. Training for Olympic rappelling after all. To this day no-one is quite sure why we didn’t just rap the crack. But having decided that traversing to the anchors of a nearby climb would give Nik and Zac a better chance of hitting the pitch three ledge, we boldly traversed across the void and began our descent…

For a moment, nothing happened. Then, after a few hours of patiently waiting… nothing continued to happen! Our ropes missed the ledge by about as far as you can throw a pink tricam, and I settled into a long hanging stance, strangely comforted by the fact that I still possessed our haul bag full of food. We were spread out over the wall, with me at the anchors, 10 meters away from terra firma, and my partners in climb hanging well out in space, 50 meters (160 feet) from each other. As it does (at the worst times, might I add), the sun got pretty bored with our confusion and flew away to illuminate Yosemite, leaving Zac to rap once more to the ground and escape around the Three Sisters in rock shoes. When Nik jugged up, I mumbled some excuse about my camera and put him on belay for the final 10-meter traverse. Since Zac had taken both the rack and lead line, our only dilemma became which of our two static ropes looked best to lead this.

|

Our next adventure was just me and Zac, but apparently “two people” doesn’t mean “two-thirds the epic of three people”. Going light, I tried pulling the rope after the second rappel and I quickly discovered that:

1. If your 3:1 rig to try and free a stuck rope lets you play Twinkle Twinkle Little Star on the line, it is indeed “proper stuck, dude.” 2. I suck at rock-paper-jumars. 3. My life is worth a fist-bump. But I accepted my fate, and quietly began jugging my rope, clipping my gear and shitting my pants. From all the times that the tourists watched us from the lookout, this was one where I would’ve much preferred to be a tourist watching us from the lookout. But to my relief (and honestly to the relief of the tourists), I freed the rope and we went down for a lap of pitch three. Back at the alcove with one pitch to go, the sun decided to do its thing again. We were armed with one bosuns chair for belaying, a haul bag with jams playing, and exactly one headlamp - which were about as useful as a lime, coconut, and a mandolin to us as the Blue Mountains stubbornly recast themselves as the “Black Mountains." As I tied in to lead the last pitch (having won scissors-paper-headlamp) the wind began to swing our haul bag in and out of Bluetooth range so that the pump-up music Zac was playing dropped out in sync with every rest stance I discovered. Instead of calling out “climbing," I yelled “tunes!” and the bag swung back in with a resounding “doof doof doof” echoing into the sunset. I think, therefore I am… photographableFinally, everything was ready. Actually, we were getting pretty good at this – fix, rap, clean, repeat… Almost too good, which seemed to be a sign to finish off the project, take some photos and move on. Zac seemed to pick up on the vibe and sent both upper pitches into orbit in good style, belayed by Gavin and taking time to pose at stances.

After we were done, I began jumaring my way out. My arms pleaded for a break, so I rested on the final ledge before the anchors. Zac had topped out above me, so I asked him whether he thought someone else had done Echo this way before - spending five rope-bound, crazy days trying to tame this monster from above, unsatisfied with a spotted, fluffy, ground-up hangdog. |

Still dazed from the effort, Zac gazed somewhat aimlessly past the Three Sisters before replying:

“Yea dude, of course!”

Hmm… I’m still not sure I echo that.

“Yea dude, of course!”

Hmm… I’m still not sure I echo that.

History of John Ewbank & Echo Crack

(by Assistant Editor Dave Barnes)

I was lucky to correspond with John Ewbank before his death who, with John Davis, put up the FA of Echo Crack on the walls below Katoomba in the Blue Mountains of Australia. He was a creative mind and a kind spirit. John was also a powerhouse of Australian climbing in the 60’s and 70’s.

The climbing grades in Australia, New Zealand and South Africa were his creation. An open ended system with 1 being its easy beginning and subsequently difficulty acknowledged as you proceed through the numbers. In Australia we currently are carving into it at grade 35.

John also broke barriers of free climbing in Australia’s establishing our first 21, Janicepts at Mount Piddington in 1966. He may have rested on it but he did the moves in sand shoes so I give him a little leeway. He also established difficult routes up and down the East Coast of the continent.

Echo Crack is a reminder to all climbers who subsequently jam the 70m corner of how brazen and bold he was. His legacy in Australian climbing is treasured by its community. He passed to the next world in 2013 from his later home in New York but lives on through the many classic climbs he established and the music he lived to write.

-- Dave Barnes, Assistant Editor Common Climber

The climbing grades in Australia, New Zealand and South Africa were his creation. An open ended system with 1 being its easy beginning and subsequently difficulty acknowledged as you proceed through the numbers. In Australia we currently are carving into it at grade 35.

John also broke barriers of free climbing in Australia’s establishing our first 21, Janicepts at Mount Piddington in 1966. He may have rested on it but he did the moves in sand shoes so I give him a little leeway. He also established difficult routes up and down the East Coast of the continent.

Echo Crack is a reminder to all climbers who subsequently jam the 70m corner of how brazen and bold he was. His legacy in Australian climbing is treasured by its community. He passed to the next world in 2013 from his later home in New York but lives on through the many classic climbs he established and the music he lived to write.

-- Dave Barnes, Assistant Editor Common Climber

SEE MORE & CONTACT ANTON KORSUN: antonkorsun.com