The tale of two mates climbing Australia's longest and arguably hardest wall route at Mount Warning (Wollumbin), NSW, Australia.

----------

----------

EDITOR'S NOTE: Wollumbin is the Aboriginal name for Mount Warning and it is considered a sacred place. Wollumbin was closed in 2020 during the COVID lock downs. During that time the Australian New South Wales National Parks and Wildlife Service (NPWS) began assessing the park's future for access, both in terms or safety and cultural protection. As of this publication (July 2022) Wollumbin is still closed. (Sources: NWPS and The Guardian)

|

Mount Warning is an iconic mountain striking out of the Great Divide on the east coast of Australia. It’s the first place the sunrays hit our continent and a wild place popular amongst hikers and nature enthusiasts. This panoramic volcano plug is close to Byron Bay in New South Wales and is striking to say the least. However, there is a dark secret and somewhat intimidating back side to this mountain! The Mount Warning Shield (also called Wollumbin) is 580 meters (1900 feet) of intimidating slab surrounded by impenetrable forest, loose rock, scree slopes, and a sense of remoteness rarely found in today's world.

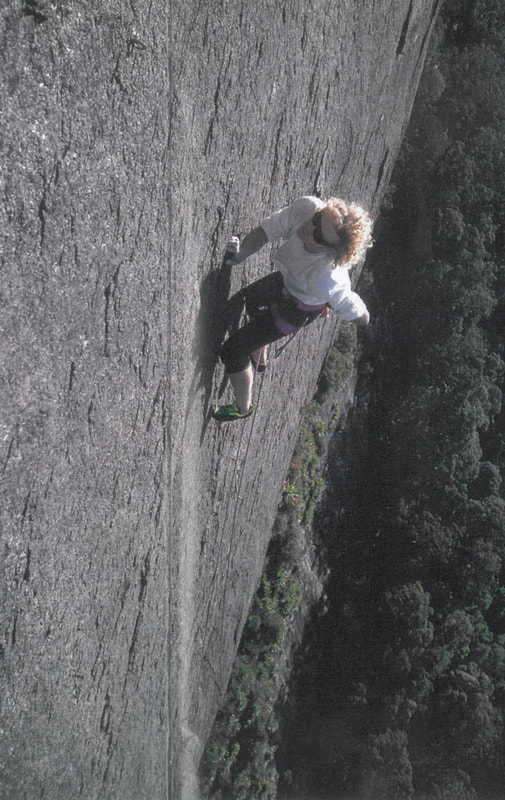

The first time I saw images of this spectacular climbing area was in Rock Magazine. Australian climbing legend, Malcolm (HB) Matheson was leading a long run out pitch on this giant black wall. He looked like a tiny dot on a giant swath of rock. I was hooked and wanted to find out more. Flicking through the mag, I was captivated with its photos highlighting a bold line carving an impressive route on a huge face. It was filled with runouts and exciting slab climbing that was sure to screw in a climber’s mind. |

|

I was twenty-two years of age and had been climbing for just two of them. I knew it was well beyond my skills and ability but reading that piece I was intrigued. How many adventures have been inspired by mags? This was one.

Fast forward eleven years and I found myself packing a monster rucksack full of climbing equipment that weighed 42 kilograms(~90 pounds). Our objective was to set a rap line then capture photos of Duncan Steel and me doing the first one day ascent of Lost Boys, an old-school grade 25 (5.11d) run out slabby climb with bolts that should’ve been in a museum. Now, more mature than when I first felt inspired by this climb, coupled with skills and a climbing partner known for his crazy hard rock climbing, I was ready to take on "da beast." We had been prepping for Lost Boys for the last five years, including doing linkups of long multipitch climbs in one day in the Dolomites of Italy, long adventure climbs in the U.S., big mountain climbing in the Himalayas, and trips to New Zealand. Meeting Duncan was one of the best - and worst - things that could have ever happened to my rock climbing career, depending on what we were doing at the time. We learned to push the limits. We learned to suffer and embrace cold, wet, and miserable adventures in remote places. And, we learned to like it. That came to be a blessing for this climb. Hiking to the bottom of Mt. Warning was ten shades of ugly. There is no marked trail, no flat ground, and there are clinging vines that trip or rip you to pieces. Then there's the scree; you take three steps forward to move one step up hill. Access is terribly slow and especially exhausting with huge, heavy packs. And that pack - every time you trip, fall, or get stuck in the surrounding forest, the pack just tips you over and you become stranded like a turtle on its back waving limbs around frantically. Once we reached base camp, we discovered the ground was wet and not level - not ideal for a tent, so we had to devise other ways to sleep. The hammock turned out to be the best. |

|

The moss covered rock at the base lead up to an imposing, dark monolith that rolled out of sight, leaving the top a visual mystery. Its presence constantly reminded us of the daunting cliff we were about to climb. I found myself asking, Why am I here? That thought was followed by this one, How the bloody hell are we going to climb this wall in a day!?

We hiked up the side of the shield to gain the top to set up a static line for photos and to rappel down to scope out the climb. As I set up the gear for the rap-in, I became spooked by the condition of the bolts and the rock. At 5 p.m., I watched the last of the sun disappear behind the Great Dividing Range thinking, I’m gonna die. Then it was eight hours of constant movement, heaving a loaded pack in an environment not meant for humans. I descended this great wall, scoping out the line we planned to climb. I noticed the run out between the bolts and what would need to happen to climb this in a day. Fear multiplied. |

I felt the rope sliding through my hand, metre after metre until I hit the next set of crap bolts that marked the next rappel station. I stopped for a minute and thought, Do I really want to clip into these rusty old bolts? I took a deep breath and slowly released the weight from my device, it was hot to touch and pressed against my leg. Duncan joined me at this rap station.

Three hours of this passed as we descended fifty metre rappels again, and again, and again…

Deep into the descent, darkness settled and a little light bubble just a few metres wide was the only thing I was focusing on. I was sitting on one single bolt, the last rap off the wall, waiting for Duncan to reach me. It had been twelve hours since we left the car. I was dehydrated, hungry, and my brain was fried. I just wanted to curl up in my sleeping bag, or just lay on the ground, for that matter.

As we walked to camp at the base of the climb, there was an eerie silence between us. I had been climbing with Duncan long enough to know that when this sort of thing happens we are both thinking deep, pondering, and planning - and that both of us are feeling a little overwhelmed.

Three hours of this passed as we descended fifty metre rappels again, and again, and again…

Deep into the descent, darkness settled and a little light bubble just a few metres wide was the only thing I was focusing on. I was sitting on one single bolt, the last rap off the wall, waiting for Duncan to reach me. It had been twelve hours since we left the car. I was dehydrated, hungry, and my brain was fried. I just wanted to curl up in my sleeping bag, or just lay on the ground, for that matter.

As we walked to camp at the base of the climb, there was an eerie silence between us. I had been climbing with Duncan long enough to know that when this sort of thing happens we are both thinking deep, pondering, and planning - and that both of us are feeling a little overwhelmed.

|

The silence was suddenly broken by the crashing sound of me falling down a rock gully for five meters, then with Duncan standing at the top laughing his head off at my misfortune. Duncan yelled down at me, “You’re going to have to work on your footwork if you want to climb this route mate!”

We set up camp, ate some grub, and fell into our bags. We talked about our feelings, the quality of the rock, and the shitty bolts we had witnessed over the last few hours. It was 11 p.m. and we were roasted. We woke at 4:30 a.m. to start our attempt at this climb. The sunrise was stunning on such a perfect winter's morning. It was a blue-sky day, but cold and windy. |

By 11 a.m. we were on a huge black west-facing wall with sweat dripping down our faces and hands. I was 6 metres (20 feet) away from my last crappy bolt, standing on coin size holds with both feet desperately looking for a handhold to grab. I saw the next bolt, two metres up and to my right.

I dipped my fingers into the chalk bag, hoping it will give my fingers more friction to hold fast to the polished black wall. I took a deep breath and a leap of faith to what I hoped was a good hold and well secured to the wall. Thankfully it was solid, unlike some of the other holds we had to pull on that day.

The climbing was slow, with precise, delicate movements. It was scary and far more difficult than I had anticipated and would have preferred. As much as possible, we left little to left to chance since we were so far from help.

By midday we decided that was enough - this was not to be the climb-in-a-day we had hoped for - and rapped down to the ground.

We continued our dance with the devil on the long line of crap bolts that eventually led us to the safety of the base. We decided to leave most of our gear there since we planned to come back to complete this bad-boy the following weekend.

I dipped my fingers into the chalk bag, hoping it will give my fingers more friction to hold fast to the polished black wall. I took a deep breath and a leap of faith to what I hoped was a good hold and well secured to the wall. Thankfully it was solid, unlike some of the other holds we had to pull on that day.

The climbing was slow, with precise, delicate movements. It was scary and far more difficult than I had anticipated and would have preferred. As much as possible, we left little to left to chance since we were so far from help.

By midday we decided that was enough - this was not to be the climb-in-a-day we had hoped for - and rapped down to the ground.

We continued our dance with the devil on the long line of crap bolts that eventually led us to the safety of the base. We decided to leave most of our gear there since we planned to come back to complete this bad-boy the following weekend.

---------

On Monday morning I woke and could hardly walk from the events suffered on the previous Saturday. Then, throughout the week, I continued my physically-intensive work as a tree climber and had little chance to rest. I was toast. I called Duncan to give him the bad news that our climbing weekend was probably not going to happen.

On the other end of the phone was dead silence….

The next weekend Duncan went on a school ski trip - he crashed and hurt his shoulder. X-rays, MRI, and a ultrasounds showed that did some pretty serious damage to his rotator cuff. This news meant he was out for two or three months.

“It's time to say goodbye to Lost Boys for 2017,” said Duncan to me on the phone as he laid in the hospital. He felt sore; I felt relief that I didn’t have to go back and try that wall again.

The gear sat at the base inside a hallowed tree for six weeks and we needed to get out and collect it. Duncan’s shoulder was not up to returning to the climb, so we did a gear retrieval trip one rainy Saturday.

“Faaaaak.”

When we arrived I discovered I had taken my large backpack out and now only had one small day pack to carry all this gear back.

Double, “Faaaaaak.”

I stuffed my bag with all the metal as I was able to and then strapped climbing ropes and a few other things to the outside. I looked like an overloaded wagon, while Duncan looked like an overloaded porter, his pack two times the size of his body. I was surprised his shoulders didn't rip out of their sockets, much less survive without reinjury.

On the other end of the phone was dead silence….

The next weekend Duncan went on a school ski trip - he crashed and hurt his shoulder. X-rays, MRI, and a ultrasounds showed that did some pretty serious damage to his rotator cuff. This news meant he was out for two or three months.

“It's time to say goodbye to Lost Boys for 2017,” said Duncan to me on the phone as he laid in the hospital. He felt sore; I felt relief that I didn’t have to go back and try that wall again.

The gear sat at the base inside a hallowed tree for six weeks and we needed to get out and collect it. Duncan’s shoulder was not up to returning to the climb, so we did a gear retrieval trip one rainy Saturday.

“Faaaaak.”

When we arrived I discovered I had taken my large backpack out and now only had one small day pack to carry all this gear back.

Double, “Faaaaaak.”

I stuffed my bag with all the metal as I was able to and then strapped climbing ropes and a few other things to the outside. I looked like an overloaded wagon, while Duncan looked like an overloaded porter, his pack two times the size of his body. I was surprised his shoulders didn't rip out of their sockets, much less survive without reinjury.

----------

The following year, winter 2018, rolled in. We had both been training hard, but neither of us talked about going back to Lost Boys. The feelings remained raw from last year's failure.

A friend said to us, “So bro, Lost Boys is run out, eh?” He continued with some statistics. “I hear the bolts were placed in 1991 and put in from the top down.”

This is true, Tim Balla hand-drilled 97 bolts (37 are anchor bolts and 20 aid climbing bolts through blank headwalls). That leaves 40 bolts over 580 metres (1900 feet) of climbing - an average of about 14.5 metres (47 feet) between bolts.

I just looked at my mate with sunken eyes and replied, “No shit, Sherlock.”

Soon after, Duncan and I were talking around the subject. We turned to each other and said telepathically, so what are you doing next weekend? We both knew the answer to the question - it was going back and attempting to do Lost Boys in a day. So we voluntarily found ourselves back in hell, forging a track to the base and sending four re-orientation pitches that same day. As I am far above the last bolt, my friend's words about run-out roll around in my head and I think, I’m a tool.

As the sun dropped behind the hills, we rapped to the ground allowing a bit more time to relax that evening. We planned to wake up at 3:30 a.m. and go for it… we had to get in as many pitches as possible before 2 p.m. since we both had to work on Monday morning. Life.

The climbing was slow per the usual traits - very long runouts with hard climbing on crap rock that would break underfoot. We had become Mount Warning feral animals.

The Traverse of Terror lives up to its name, grade 17 (5.9) with one bolt for 45 metres (150 feet). The next grade 19 (5.10b) pitch was sketchy with three bolts in 50m (165 feet) in length. Lastly, my favourite grade, 23 (5.11b) with 45m and just five bolts. Far canal.

A friend said to us, “So bro, Lost Boys is run out, eh?” He continued with some statistics. “I hear the bolts were placed in 1991 and put in from the top down.”

This is true, Tim Balla hand-drilled 97 bolts (37 are anchor bolts and 20 aid climbing bolts through blank headwalls). That leaves 40 bolts over 580 metres (1900 feet) of climbing - an average of about 14.5 metres (47 feet) between bolts.

I just looked at my mate with sunken eyes and replied, “No shit, Sherlock.”

Soon after, Duncan and I were talking around the subject. We turned to each other and said telepathically, so what are you doing next weekend? We both knew the answer to the question - it was going back and attempting to do Lost Boys in a day. So we voluntarily found ourselves back in hell, forging a track to the base and sending four re-orientation pitches that same day. As I am far above the last bolt, my friend's words about run-out roll around in my head and I think, I’m a tool.

As the sun dropped behind the hills, we rapped to the ground allowing a bit more time to relax that evening. We planned to wake up at 3:30 a.m. and go for it… we had to get in as many pitches as possible before 2 p.m. since we both had to work on Monday morning. Life.

The climbing was slow per the usual traits - very long runouts with hard climbing on crap rock that would break underfoot. We had become Mount Warning feral animals.

The Traverse of Terror lives up to its name, grade 17 (5.9) with one bolt for 45 metres (150 feet). The next grade 19 (5.10b) pitch was sketchy with three bolts in 50m (165 feet) in length. Lastly, my favourite grade, 23 (5.11b) with 45m and just five bolts. Far canal.

If either of us fell on any of these three pitches, we would see a huge swing, over sharp edges, 200m off the ground. We both knew it was no- fall territory.

One more pitch saw us at the halfway ledge. Unfortunately, that ledge is not that big and not that flat. It was not restful. It was also hot as hell and we had to head home soon anyway. Another failure... I decided to leave water and spare food at that ledge just in case we attempted this insanity again.

I was mentally drained from the climbing and took a minute to assess my feelings at the bottom as I waited for Duncan to reach the ground. Despite leaving the food on the ledge, it played back in my mind like this, “I ain’t coming back; not now, not later, not ever.”

On the drive home there was very little talk between us. Normally this would seem unusual, but in this circumstance it seemed fine for both of us. As we got closer to my place I blurted out, “I'm going to need a week off from you.”

I took the weekend off to climb with my girlfriend at a place I hadn't been for some time. I was broken. I had used everything on Lost Boys the previous weekend. I didn't climb well. I had flashbacks of the climb. This gave me a chance to explore whether Lost Boys was something I really wanted to do or if I could even do it at all. I realized that climbing at that place was scary - even if it was below my normal grade.

That weekend was important for me to clear my mind, rest my body, and reconnect with myself. At the end of the weekend, I knew what I wanted to do, but decided to wait to say something to Duncan. When he texted - and then when we did our Tuesday climbing session - I could tell he was chomping at the bit to ask me about going back to the wall. I wanted to play with his emotions and feelings just for a little bit longer, so I kept quiet.

Towards the end of our climbing session that day, I casually said, “So mate, are you free next weekend?”

You should have seen the smile that stretched from ear to ear on Duncan's face. I knew that he knew straight away what the answer was. We both agreed to leave early Saturday morning.

I realized I had forgotten to tell my girlfriend I was going to go back for more pain and suffering. I revealed the plans the Thursday night before. She took my news well and said, “I thought it was only a matter of time until you went back. Enjoy yourself and be safe.” She had a loving smile on her face.

One more pitch saw us at the halfway ledge. Unfortunately, that ledge is not that big and not that flat. It was not restful. It was also hot as hell and we had to head home soon anyway. Another failure... I decided to leave water and spare food at that ledge just in case we attempted this insanity again.

I was mentally drained from the climbing and took a minute to assess my feelings at the bottom as I waited for Duncan to reach the ground. Despite leaving the food on the ledge, it played back in my mind like this, “I ain’t coming back; not now, not later, not ever.”

On the drive home there was very little talk between us. Normally this would seem unusual, but in this circumstance it seemed fine for both of us. As we got closer to my place I blurted out, “I'm going to need a week off from you.”

I took the weekend off to climb with my girlfriend at a place I hadn't been for some time. I was broken. I had used everything on Lost Boys the previous weekend. I didn't climb well. I had flashbacks of the climb. This gave me a chance to explore whether Lost Boys was something I really wanted to do or if I could even do it at all. I realized that climbing at that place was scary - even if it was below my normal grade.

That weekend was important for me to clear my mind, rest my body, and reconnect with myself. At the end of the weekend, I knew what I wanted to do, but decided to wait to say something to Duncan. When he texted - and then when we did our Tuesday climbing session - I could tell he was chomping at the bit to ask me about going back to the wall. I wanted to play with his emotions and feelings just for a little bit longer, so I kept quiet.

Towards the end of our climbing session that day, I casually said, “So mate, are you free next weekend?”

You should have seen the smile that stretched from ear to ear on Duncan's face. I knew that he knew straight away what the answer was. We both agreed to leave early Saturday morning.

I realized I had forgotten to tell my girlfriend I was going to go back for more pain and suffering. I revealed the plans the Thursday night before. She took my news well and said, “I thought it was only a matter of time until you went back. Enjoy yourself and be safe.” She had a loving smile on her face.

---------

By now we could practically do the approach blindfolded. We punched it out in great time - three hours - our best walk in yet.

We dropped our packs and ran up the first four pitches to rehearse them for tomorrow morning's early start. By 6:25 p.m. it was freezing cold, so we crawled into our sleeping bags.

At 3:20 a.m. I stirred before the alarm rang at 3:30. I was nervous and a little bit scared, but I managed to force down some breakfast. I unzipped my sleeping bag and rose to the frigid air.

At 4 a.m. Duncan took the first step off the ground. It was game on. I stood in the dark to both save power and to not to shine my light over this massive wall, reminding me what were about to attempt.

It's so hard climbing slab in the dark by a head torch, you can't see your footholds. I felt the ropes stop and I knew it was my time to force my feet into my shoes. Despite the precise footwork needed, my shoes were slightly larger than I'd normally wear since I would have them on for the next 12 or more hours.

The rope pulled tight on my harness, signaling it was my turn to leave the safety of the ground. I climbed quickly knowing I had the safety of the rope securing me from above. I thought, Wow, Duncan did so well to lead this in the dark.

As I pulled over the edge to where he was standing we swapped gear and I switched my mind from neutral to first. It was time to rev this worn engine of mine.

My pitch went smoothly and fast thanks to the many times I had done it. As I pulled the rope taut for Duncan and had a look around, the nearly-full moon and stars were out in full glory, but it was finger-numbing cold. I watched Duncan's bubble of light inch its way closer to me occasionally shining into my eyes, then shining elsewhere. These flickers left me blurry for vision. We achieved two more pitches in the dark and, just like before, we moved slowly and efficiently over the long, run out, crumble-fest.

I was relieved to see the sky turn from jet black to a warm orange glow. This is the coldest time of day and I pulled my down jacket over my helmet to stay warm. Duncan finished off pitch six and by the time I had reached him, there was just enough light to turn off my head torch.

We talked about how good our timing was as I launched off the belay and onto the first pitch of that traverse of terror. We moved stealthily through the next two pitches, stopping for a few minutes to eat some food before I set off for the pitch graded 23.

Midway across, I looked down to see a hold broken under my foot, only to realise I was standing on a very tiny hole within a hairline crack. I caught Duncan's eye and he smiled back at me. I was far above last bolt with a considerable amount of rope dangling below the overhang. I stepped back onto another hold and repeated in my head, I must not fall, I must not fall here. Somehow, the mantra worked. Before long we were standing on a grassy ledge, the size of a single bed. To my horror we discovered that rodents had eaten all the food I left here last time. They even chewed a hole in the water bottle and drained it empty. I really could have done with some water and a chocolate bar.

To top it off, Duncan needed to poo - while I was downwind of course! I flashed back to 2015 on our Nepal climbing trip to Ama Dablam where I had to cut off his undies after explosive diarrhea at Camp One, at around 5800 meters. It was nearly -27 degrees Celsius (-16 F) and he couldn't get his undies on over his monstrous mountain climbing boots.

With Duncan's bodily needs completed, it was on to the untried part of this wall. Although I passed these spots by head torch more than a year ago when we were abseiling down, I was too exhausted to take in any of it. We were now venturing into the world of mostly unknowns.

Some of the old faded and perished rope was still blowing in the wind off to our left. They served as one more reminder of my mental anguish of this wall. From here on up the climb became even harder and the bolts became further spaced.

As we switched leads, we didn’t say much. There was small talk like “How you doing?” as we passed each other at the belay. Duncan and I have climbed so much together, we can read each other like a book. We both already knew that we were scared, tired, and our feet were hurting like hell. Yet, we put on a brave face, smiled, and said, “Yeah, I'm going good” or “I'm okay."

There’s a saying; a picture paints a thousand words. Those thousand words were completely different to what we were saying out aloud.

We dropped our packs and ran up the first four pitches to rehearse them for tomorrow morning's early start. By 6:25 p.m. it was freezing cold, so we crawled into our sleeping bags.

At 3:20 a.m. I stirred before the alarm rang at 3:30. I was nervous and a little bit scared, but I managed to force down some breakfast. I unzipped my sleeping bag and rose to the frigid air.

At 4 a.m. Duncan took the first step off the ground. It was game on. I stood in the dark to both save power and to not to shine my light over this massive wall, reminding me what were about to attempt.

It's so hard climbing slab in the dark by a head torch, you can't see your footholds. I felt the ropes stop and I knew it was my time to force my feet into my shoes. Despite the precise footwork needed, my shoes were slightly larger than I'd normally wear since I would have them on for the next 12 or more hours.

The rope pulled tight on my harness, signaling it was my turn to leave the safety of the ground. I climbed quickly knowing I had the safety of the rope securing me from above. I thought, Wow, Duncan did so well to lead this in the dark.

As I pulled over the edge to where he was standing we swapped gear and I switched my mind from neutral to first. It was time to rev this worn engine of mine.

My pitch went smoothly and fast thanks to the many times I had done it. As I pulled the rope taut for Duncan and had a look around, the nearly-full moon and stars were out in full glory, but it was finger-numbing cold. I watched Duncan's bubble of light inch its way closer to me occasionally shining into my eyes, then shining elsewhere. These flickers left me blurry for vision. We achieved two more pitches in the dark and, just like before, we moved slowly and efficiently over the long, run out, crumble-fest.

I was relieved to see the sky turn from jet black to a warm orange glow. This is the coldest time of day and I pulled my down jacket over my helmet to stay warm. Duncan finished off pitch six and by the time I had reached him, there was just enough light to turn off my head torch.

We talked about how good our timing was as I launched off the belay and onto the first pitch of that traverse of terror. We moved stealthily through the next two pitches, stopping for a few minutes to eat some food before I set off for the pitch graded 23.

Midway across, I looked down to see a hold broken under my foot, only to realise I was standing on a very tiny hole within a hairline crack. I caught Duncan's eye and he smiled back at me. I was far above last bolt with a considerable amount of rope dangling below the overhang. I stepped back onto another hold and repeated in my head, I must not fall, I must not fall here. Somehow, the mantra worked. Before long we were standing on a grassy ledge, the size of a single bed. To my horror we discovered that rodents had eaten all the food I left here last time. They even chewed a hole in the water bottle and drained it empty. I really could have done with some water and a chocolate bar.

To top it off, Duncan needed to poo - while I was downwind of course! I flashed back to 2015 on our Nepal climbing trip to Ama Dablam where I had to cut off his undies after explosive diarrhea at Camp One, at around 5800 meters. It was nearly -27 degrees Celsius (-16 F) and he couldn't get his undies on over his monstrous mountain climbing boots.

With Duncan's bodily needs completed, it was on to the untried part of this wall. Although I passed these spots by head torch more than a year ago when we were abseiling down, I was too exhausted to take in any of it. We were now venturing into the world of mostly unknowns.

Some of the old faded and perished rope was still blowing in the wind off to our left. They served as one more reminder of my mental anguish of this wall. From here on up the climb became even harder and the bolts became further spaced.

As we switched leads, we didn’t say much. There was small talk like “How you doing?” as we passed each other at the belay. Duncan and I have climbed so much together, we can read each other like a book. We both already knew that we were scared, tired, and our feet were hurting like hell. Yet, we put on a brave face, smiled, and said, “Yeah, I'm going good” or “I'm okay."

There’s a saying; a picture paints a thousand words. Those thousand words were completely different to what we were saying out aloud.

It was my turn to lead. As I moved up, my protection was tapping hollow, reverberating noises in the rock face. I could hear a dull thud of the detached sheet of rock on which I was standing. I was now 10 metres (30 feet) past the last bolt on a slab of rock the size of a house roof! I was rattled, but not as much as the block.

I saw a hole approximately 2 metres up and to my left. I slowly inched closer to this weirdness. My mind was dribble, but my resolve was fast - fear can work to your favour. I worked the gap and was now standing above it.

I could hear Duncan calling out, he was trying to let me know something important between the gusts of wind. When the wind died for a moment, I heard his faint call, “Don’t you dare! Don’t even think about it, just-keep-climbing!” He knew I wanted to put some gear behind this loose flake on this tethering slab, which could potentially lever off this huge shield of rock, sending it down towards Duncan at the belay along with me on it. It was Evil Knievel stuff, not a good place to have no gear and looking like a long way until some sense of security at the next bolt.

I was at a point of dilemma: If I don't put the protection in the hole I could possibility take a 25 metre-plus fall. If I do put the gear into the hole, I risk dislodging a huge sheet of rock which could potentially cut the rope and take Duncan and me all the way to the ground with it.

I paused and assessed the run out, looking skyward to establish how far it was until the salvation bolt. Peering down at Duncan, and with a cheeky smile, I reached down and slipped some suspect pro into the hollow. The sound it made sent shivers down my spine. I continued upwards, finding a gap between the slab and the vertical wall which I could slip my hands behind. I discovered that rock I had been climbing on for the last 25 minutes was completely detached. Somehow it was just resting on the slab.

When Duncan arrived at the belay, I was somewhat annoyed he did not take the time to make a video of this section. He brought me back to reality, barking, “I'm not bloody stopping on this death block to take a stupid video mate!”

The madness just did not let up.

Duncan was now off questing on another hard pitch. These upper pitches followed basically the same layout; slab for 30 metres followed by a steep headwall, followed by the next slab at an anchor. If you were to fall on the hard climbing up the headwall it would send you plummeting straight down onto the slab below. As Duncan was closing in on the lip of the headwall, the worn fixed rope we rapped down on was in his way. He called to me,

“Flick the fucker outta my way!”

I tried to but the rope got snagged on a rock higher up. I flicked it again, this time the rope moved but so did a shield-sized piece of rock. Mayhem. Maybe 30 meters above Duncan I screamed, “Rock!” It was the most gut-wrenching cry as it was heading straight for us.

At this point we both tried to make our bodies fit underneath our helmets but it was like fitting three people under a small umbrella on a rainy day. It smashed on the slab 20 meters above Duncan, breaking into 100,000 pieces. We tried to press our bodies into the wall, but one piece hit Duncan's helmet and put a huge crack in it. Another hit me on the right arm.

I wish I could say the climbing got better, but it didn't.

Once more the sky turned orange as the sun began to set behind the mountains leaving us alone on this black coffin of a wall. We were now high enough up the face and able to see house lights in the valley and cars winding their way up and down the mountainside. This reinforced how far away from everything we really were - and that we had been climbing non-stop for 13 hours.

To say I was physically tired, is an understatement. But, this was not unusual. It was something I've felt many times before with Duncan. What was new is how wrecked I was mentally, not only from the hard and nightmare climbing, but also from not having time to nurture a mental break while on belay - it was terrifying to watch your friend on these run out sections with loose rock.

We donned our head torches and continued to siege up this never-ending wall of choss. Seeing the moonlight peek through the trees at the top was a welcomed sight.

I allowed myself to exhale and smile, since I knew the last pitch was easy climbing, but it didn't take long for the smile to disappear. I climbed over rocks the size of microwaves, held in place only by dirt. I grabbed spiky shrubs in near desperation to reach the top. Each spike and boulder reminded me how terrible this climb had been all day.

Yet, here we were - 15 hours after leaving the safety of the ground, both of us were standing - relatively unscathed - on the summit.

Yes!! We had made the first one-day ascent of Australia's longest and hardest mixed climb. As grateful and excited as we were, there was very little left in us to celebrate. We had five minutes to eat the remaining food left in our backpacks and made a quick video. Looking at this video later I could see how wasted I really looked.

We found the old fixed ropes and the shoes left there over a year ago. The bag was disintegrated and trashed from the sun, but the shoes were still there. They were wet and mouldy, but I wasted no time putting them on, as I couldn’t face the thought of putting my feet back into my tight climbing shoes.

Without saying a word, Duncan rapped off the old fixed rope and left me stranded with no choice but to follow him. While descending I became super uncomfortable, pissed off, and stuck. I couldn't get the GriGri to run through the fixed line. I was now free hanging over a lip in space, unable to move. I tried as hard as I could to force the rope through the device only able to move 10 centimeters at a time. I could hear the rope squeaking. I shined my head torch on my device wondering, Have I broken it or is it damaged? What's wrong with this bloody thing? It took a few minutes for my brain to realise that the problem was the rope had swollen significantly in size.

I quickly recognize that I'm going to have to change from my GriGri to an ATC. I take a deep breath and start the process, carefully taking each step to make sure my tired brain does not make a fatal mistake. It takes me 10 minutes to do this transfer. By this stage I'm really terrified of the quality of the rope below. I'm now free to abseil down the old fixed rope and can feel the lumps and bumps passed through my hand as I make a very gentle abseil towards the belay where Duncan is waiting. I came to a huge wear spot in the rope where, for the last year it had been blowing on a sharp edge and had worn the sheath of the rope completely to the core.

I first see it via my head lamp, then feel it as my hand runs over it. I stopped for a second knowing my only option was to continue past it. I took the breath of a deep diver and, without much thought, let the damaged part of the rope pass through the device. I tried not to look, but my light illuminated that messed up crap as it passed through.

I reached the belay, then clipped in to a very welcomed safety. I sighed a huge relief and then could not control the shuddering of my body. Duncan's face was as white as a ghost. Without saying a word, we returned to our climbing ropes to descend the rest of the way down this huge wall.

After having pulled the rope at every abseil of 50 meters, we got into a rhythm. Three hours passed. At 9:30 p.m. we reached the ground, then shook hands to congratulate each other. We collapsed onto our backpacks with our backs against the wall. It was still warm from the day's sunlight. We didn’t say much other than,

“How big would’ve that fall have been after you'd run it out for 20m above the slab?”

And, “How much harder was that climb than you first expected?”

And, “I can't believe we just did that."

We groaned as we stood painfully on sore feet and hobbled back to camp.

We both knew not to get into the sleeping bags, as we wouldn’t get out again. In a haze, we packed up camp at 10:30 p.m. -19 hours after first leaving this spot. We lifted those heavy backpacks on tired shoulders and took our first steps, which were more like newborn babies trying to walk for the first time. This awkwardness continued as we zombied down the steep, rocky, embankment, with our 35 kilogram packs as bondage.

Having to retrace our path back to the car was slow going, worse still with the doubly dark night in the thick forest. We trudged slowly, careful not to miss the track, with its hundreds of turns. At one point we meandered off route, walking into a wall of sharp spiky vines, which cut us out of a dazed sleep born of deprivation from the vertical struggle. Having this happen forced us to concentrate harder and not to miss the track again because the painful reminder sucks.

We hit the gravel road and knew it was only 30 minutes until the end. It was now 1 a.m. and our pace was painfully slow, but we knew the weight of those backpacks would soon be relieved as we dumped them in the car. The thought of that rose our spirits and we began to joke about other epics we had shared. This helped time pass by more quickly.

Deliverance.

I saw a hole approximately 2 metres up and to my left. I slowly inched closer to this weirdness. My mind was dribble, but my resolve was fast - fear can work to your favour. I worked the gap and was now standing above it.

I could hear Duncan calling out, he was trying to let me know something important between the gusts of wind. When the wind died for a moment, I heard his faint call, “Don’t you dare! Don’t even think about it, just-keep-climbing!” He knew I wanted to put some gear behind this loose flake on this tethering slab, which could potentially lever off this huge shield of rock, sending it down towards Duncan at the belay along with me on it. It was Evil Knievel stuff, not a good place to have no gear and looking like a long way until some sense of security at the next bolt.

I was at a point of dilemma: If I don't put the protection in the hole I could possibility take a 25 metre-plus fall. If I do put the gear into the hole, I risk dislodging a huge sheet of rock which could potentially cut the rope and take Duncan and me all the way to the ground with it.

I paused and assessed the run out, looking skyward to establish how far it was until the salvation bolt. Peering down at Duncan, and with a cheeky smile, I reached down and slipped some suspect pro into the hollow. The sound it made sent shivers down my spine. I continued upwards, finding a gap between the slab and the vertical wall which I could slip my hands behind. I discovered that rock I had been climbing on for the last 25 minutes was completely detached. Somehow it was just resting on the slab.

When Duncan arrived at the belay, I was somewhat annoyed he did not take the time to make a video of this section. He brought me back to reality, barking, “I'm not bloody stopping on this death block to take a stupid video mate!”

The madness just did not let up.

Duncan was now off questing on another hard pitch. These upper pitches followed basically the same layout; slab for 30 metres followed by a steep headwall, followed by the next slab at an anchor. If you were to fall on the hard climbing up the headwall it would send you plummeting straight down onto the slab below. As Duncan was closing in on the lip of the headwall, the worn fixed rope we rapped down on was in his way. He called to me,

“Flick the fucker outta my way!”

I tried to but the rope got snagged on a rock higher up. I flicked it again, this time the rope moved but so did a shield-sized piece of rock. Mayhem. Maybe 30 meters above Duncan I screamed, “Rock!” It was the most gut-wrenching cry as it was heading straight for us.

At this point we both tried to make our bodies fit underneath our helmets but it was like fitting three people under a small umbrella on a rainy day. It smashed on the slab 20 meters above Duncan, breaking into 100,000 pieces. We tried to press our bodies into the wall, but one piece hit Duncan's helmet and put a huge crack in it. Another hit me on the right arm.

I wish I could say the climbing got better, but it didn't.

Once more the sky turned orange as the sun began to set behind the mountains leaving us alone on this black coffin of a wall. We were now high enough up the face and able to see house lights in the valley and cars winding their way up and down the mountainside. This reinforced how far away from everything we really were - and that we had been climbing non-stop for 13 hours.

To say I was physically tired, is an understatement. But, this was not unusual. It was something I've felt many times before with Duncan. What was new is how wrecked I was mentally, not only from the hard and nightmare climbing, but also from not having time to nurture a mental break while on belay - it was terrifying to watch your friend on these run out sections with loose rock.

We donned our head torches and continued to siege up this never-ending wall of choss. Seeing the moonlight peek through the trees at the top was a welcomed sight.

I allowed myself to exhale and smile, since I knew the last pitch was easy climbing, but it didn't take long for the smile to disappear. I climbed over rocks the size of microwaves, held in place only by dirt. I grabbed spiky shrubs in near desperation to reach the top. Each spike and boulder reminded me how terrible this climb had been all day.

Yet, here we were - 15 hours after leaving the safety of the ground, both of us were standing - relatively unscathed - on the summit.

Yes!! We had made the first one-day ascent of Australia's longest and hardest mixed climb. As grateful and excited as we were, there was very little left in us to celebrate. We had five minutes to eat the remaining food left in our backpacks and made a quick video. Looking at this video later I could see how wasted I really looked.

We found the old fixed ropes and the shoes left there over a year ago. The bag was disintegrated and trashed from the sun, but the shoes were still there. They were wet and mouldy, but I wasted no time putting them on, as I couldn’t face the thought of putting my feet back into my tight climbing shoes.

Without saying a word, Duncan rapped off the old fixed rope and left me stranded with no choice but to follow him. While descending I became super uncomfortable, pissed off, and stuck. I couldn't get the GriGri to run through the fixed line. I was now free hanging over a lip in space, unable to move. I tried as hard as I could to force the rope through the device only able to move 10 centimeters at a time. I could hear the rope squeaking. I shined my head torch on my device wondering, Have I broken it or is it damaged? What's wrong with this bloody thing? It took a few minutes for my brain to realise that the problem was the rope had swollen significantly in size.

I quickly recognize that I'm going to have to change from my GriGri to an ATC. I take a deep breath and start the process, carefully taking each step to make sure my tired brain does not make a fatal mistake. It takes me 10 minutes to do this transfer. By this stage I'm really terrified of the quality of the rope below. I'm now free to abseil down the old fixed rope and can feel the lumps and bumps passed through my hand as I make a very gentle abseil towards the belay where Duncan is waiting. I came to a huge wear spot in the rope where, for the last year it had been blowing on a sharp edge and had worn the sheath of the rope completely to the core.

I first see it via my head lamp, then feel it as my hand runs over it. I stopped for a second knowing my only option was to continue past it. I took the breath of a deep diver and, without much thought, let the damaged part of the rope pass through the device. I tried not to look, but my light illuminated that messed up crap as it passed through.

I reached the belay, then clipped in to a very welcomed safety. I sighed a huge relief and then could not control the shuddering of my body. Duncan's face was as white as a ghost. Without saying a word, we returned to our climbing ropes to descend the rest of the way down this huge wall.

After having pulled the rope at every abseil of 50 meters, we got into a rhythm. Three hours passed. At 9:30 p.m. we reached the ground, then shook hands to congratulate each other. We collapsed onto our backpacks with our backs against the wall. It was still warm from the day's sunlight. We didn’t say much other than,

“How big would’ve that fall have been after you'd run it out for 20m above the slab?”

And, “How much harder was that climb than you first expected?”

And, “I can't believe we just did that."

We groaned as we stood painfully on sore feet and hobbled back to camp.

We both knew not to get into the sleeping bags, as we wouldn’t get out again. In a haze, we packed up camp at 10:30 p.m. -19 hours after first leaving this spot. We lifted those heavy backpacks on tired shoulders and took our first steps, which were more like newborn babies trying to walk for the first time. This awkwardness continued as we zombied down the steep, rocky, embankment, with our 35 kilogram packs as bondage.

Having to retrace our path back to the car was slow going, worse still with the doubly dark night in the thick forest. We trudged slowly, careful not to miss the track, with its hundreds of turns. At one point we meandered off route, walking into a wall of sharp spiky vines, which cut us out of a dazed sleep born of deprivation from the vertical struggle. Having this happen forced us to concentrate harder and not to miss the track again because the painful reminder sucks.

We hit the gravel road and knew it was only 30 minutes until the end. It was now 1 a.m. and our pace was painfully slow, but we knew the weight of those backpacks would soon be relieved as we dumped them in the car. The thought of that rose our spirits and we began to joke about other epics we had shared. This helped time pass by more quickly.

Deliverance.

We had arrived at our vehicle and dropped our packs for the last time. We dumped them straight into the trunk and fell into the seats totally pulped. We swapped stories about which body parts hurt the most.

The drive home was a blur. We promised each other to stay awake to help the driver stay alert and focused on the road. We switched driving three or four times and arrived home at 4:30 a.m. - more than 24 hours since we had started this climb.

Home.

I tossed my bag outside and headed straight for a hot shower. The water refreshed me as it ran over my head, but once it hit my body it stung; every little cut, every little scratch that I had collected from the last two days pained me. I was too exhausted to stand. I sat, leaning against the wall with the water pouring over me.I have no idea how long I sat there.

I climbed into bed, my girlfriend rolled over and said, “Congratulations on climbing Lost Boys. I'm so glad you two survived it.”

All too soon, my alarm rang at 6:45 a.m. Time for work. My feet were swollen so badly I couldn’t fit them into my work boots. I decided to wear the biggest, loosest pair of running shoes I own. As I walked out the door for a 10-hour shift, I wondered, Why do I do this?

Lost Boys in a day. Most folks said, "No way." But, two lost boys entered that forest, climbed that wall, and two really great friends - along with some hard boys - exited.

The drive home was a blur. We promised each other to stay awake to help the driver stay alert and focused on the road. We switched driving three or four times and arrived home at 4:30 a.m. - more than 24 hours since we had started this climb.

Home.

I tossed my bag outside and headed straight for a hot shower. The water refreshed me as it ran over my head, but once it hit my body it stung; every little cut, every little scratch that I had collected from the last two days pained me. I was too exhausted to stand. I sat, leaning against the wall with the water pouring over me.I have no idea how long I sat there.

I climbed into bed, my girlfriend rolled over and said, “Congratulations on climbing Lost Boys. I'm so glad you two survived it.”

All too soon, my alarm rang at 6:45 a.m. Time for work. My feet were swollen so badly I couldn’t fit them into my work boots. I decided to wear the biggest, loosest pair of running shoes I own. As I walked out the door for a 10-hour shift, I wondered, Why do I do this?

Lost Boys in a day. Most folks said, "No way." But, two lost boys entered that forest, climbed that wall, and two really great friends - along with some hard boys - exited.

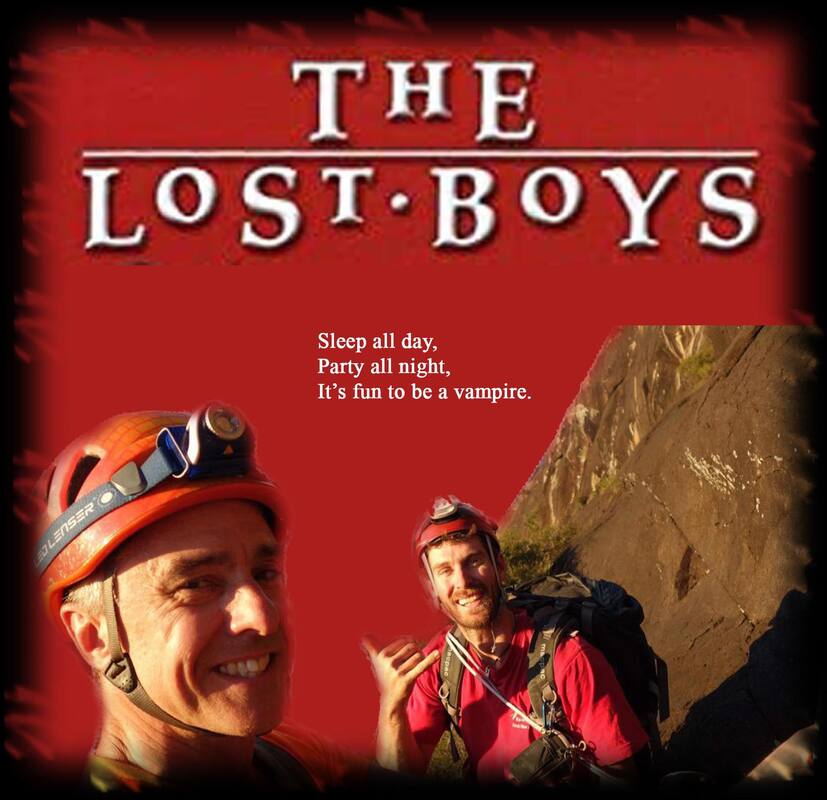

EDITOR'S COMMENT: Lost Boys was a teen cult classic made in 1987. Starring uber teen Hollywood heartthrobs, it mixed horror with 80’s rock and vampires which had never looked so cool. The original Lost Boys climbers named their climb after this film. The parallels are many. Cool kids of the climbing counter culture walking into a dark place that wants to kill them but teases them slowly with wild climbing. Only a wicked team of climbers could rise above that darkness. That’s what the original party did and so righteous that they rose through the hardship to complete the mission. The later party followed in the footsteps of these slayers and The Lost Boys prevail; in the movie, during the FA and recently when another two adventure find their way to the send. Wicked bros.