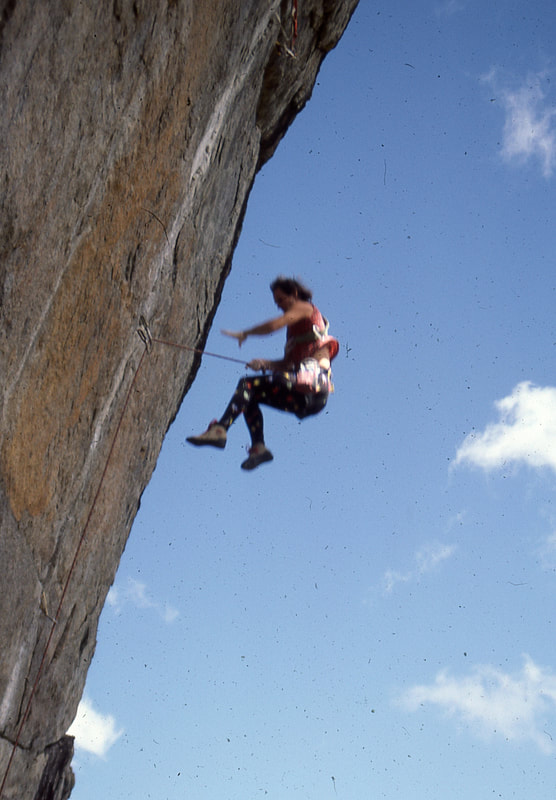

It happened in an instant, almost by surprise. I was making the crux move, thirty feet off the ground, feet smeared out on a slick overhanging wall, reaching up from a sloping knob to a jug that was just out of reach. It was close, so close, and impulsively I lunged for it. And missed. And then I was falling.

I swore out loud, upset that I’d missed the hold, but not concerned about falling. I could have fought to hang on, but in the split-second between missing the hold and starting to fall I did the calculus and decided no, it was okay to let go. I’d fallen before and nothing bad had happened. It would be scary for a second and then it would be over. I’d sewn up the crack leading up to the crux. I had a good stopper in a few feet down and to my left, and another every three feet below that. I’d take a short fall, feel a little jerk on the rope as my belayer caught me, then lower off and try again.

But the expected jerk on the rope never came.

Instead, there was a light scraping of metal on rock, then pop-pop-pop! like steel cable going taut and snapping strand by strand, the rush of air, impact, and a disorientating tumble backwards down a slab.

It was over before I knew it, a second at most, yet it felt as if I was falling in slow motion, calmly watching the whole thing play out, helplessly aware of everything that was going wrong. I was falling fast. All of my protection was pulling out. I was going to hit the ground. I was going to die. I was pretty sure of it, although it didn’t particularly concern me. It seemed like the inevitable outcome. My fate was sealed. There was nothing I could do.

I swore out loud, upset that I’d missed the hold, but not concerned about falling. I could have fought to hang on, but in the split-second between missing the hold and starting to fall I did the calculus and decided no, it was okay to let go. I’d fallen before and nothing bad had happened. It would be scary for a second and then it would be over. I’d sewn up the crack leading up to the crux. I had a good stopper in a few feet down and to my left, and another every three feet below that. I’d take a short fall, feel a little jerk on the rope as my belayer caught me, then lower off and try again.

But the expected jerk on the rope never came.

Instead, there was a light scraping of metal on rock, then pop-pop-pop! like steel cable going taut and snapping strand by strand, the rush of air, impact, and a disorientating tumble backwards down a slab.

It was over before I knew it, a second at most, yet it felt as if I was falling in slow motion, calmly watching the whole thing play out, helplessly aware of everything that was going wrong. I was falling fast. All of my protection was pulling out. I was going to hit the ground. I was going to die. I was pretty sure of it, although it didn’t particularly concern me. It seemed like the inevitable outcome. My fate was sealed. There was nothing I could do.

|

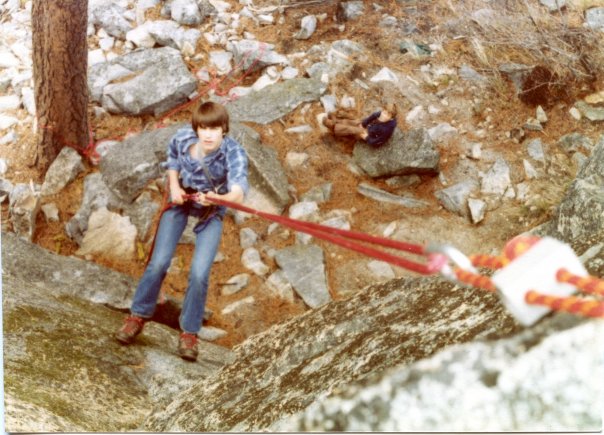

When I was fifteen, I decided that climbing was something I desperately wanted to do. It took some convincing, but my parents finally allowed me to sign up for a mountaineering course with an outfit called Northwest Alpine Guide Service that operated out of a loft in an old brick building across the street from the Greyhound terminal in Seattle. Our instructor, Brad Bradley, was a serious-minded man with crew-cut hair and dark, horn-rimmed glasses, who preached safety first. He taught us how to belay, rappel, prusik, self-arrest, place anchors, tie knots, treat injuries, evacuate injured climbers—everything we needed to know, he said—his way, which was, he insisted, the right way. He was so strict that he insisted we learn to tie knots one-handed while taking a cold shower, so we would be prepared when that life-or-death moment arrived on the side of a mountain wall when, during a fierce hailstorm, we would be able to tie a knot with one hand while clinging to dear life with the other. He assured us this would happen. We believed him.

Brad also imparted his brand of wisdom to the class, which included telling us that at least one person in the class was going to die in a climbing accident. He said that in our first year of climbing, we would have no idea what we were doing and would be lucky not to forget to tie into the rope and fall to our deaths. In our second year, we might think we knew what we were doing but, honestly, we'd still have no clue and would likely end up trying to climb something we really had no business climbing, then fall off, have all of our gear pull out, and be smashed into the ground. In our third year, if we lived that long, we would be certain we knew what we were doing, just the sort of hubris that would precipitate disaster, the kind of disaster that would involve collateral damage—an entire-climbing-party-vanishing-forever kind of disaster, or worse. What worse was, he didn’t say, except that it would be the lead story on the evening news and everyone would know how stupidly we died. |

But there was good news: If we survived our third year of climbing, Brad assured us, we would have survived innumerable near-death experiences, learned from our incalculable mistakes, tamed our unbridled egos, become less readily inclined to foolishly push our luck, and climb for many happy years. Either that or we would have come to our senses, realized that climbing is a stupid, selfish, dangerous, fundamentally anti-social sport, and quit forever. Or we wouldn’t, and would go on bumbling away at it, thinking we were pretty good climbers, when in reality it was just dumb luck that we survived.

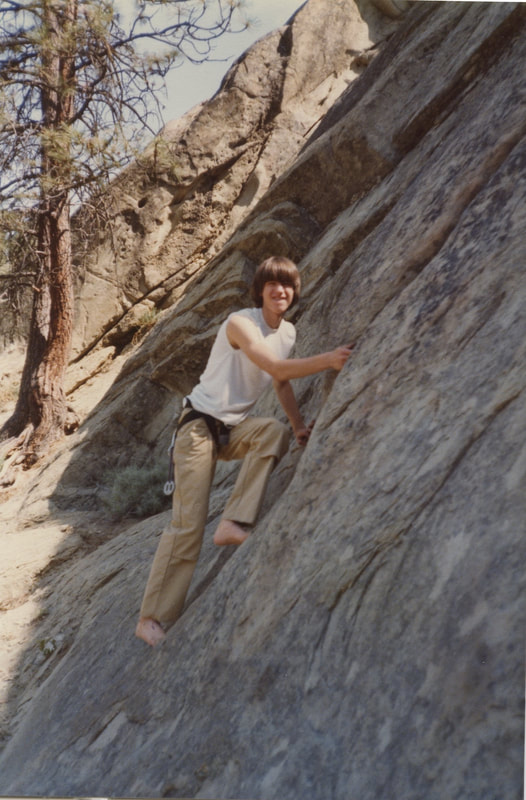

I made it through my first year of climbing without incident. No falls, no accidents, nothing. I tied in carefully, double-checked knots, backed up rappel anchors and everything, just the way Brad had taught us. I chose routes carefully, sticking to easy climbs not far off the ground. So far so good. By my second year, I started feeling confident, like I knew what I was doing.

I made it through my first year of climbing without incident. No falls, no accidents, nothing. I tied in carefully, double-checked knots, backed up rappel anchors and everything, just the way Brad had taught us. I chose routes carefully, sticking to easy climbs not far off the ground. So far so good. By my second year, I started feeling confident, like I knew what I was doing.

|

Naturally, I got addicted to rock climbing and became keenly interested in how hard a route was and what it was rated. Brad had warned us about ratings, that we should use them with caution to stay off of routes that were too difficult for our ability level—to avoid getting in over our heads—but if we wanted to go and do something foolish like try a 5.6 rock climb, we were asking for trouble.

In his book, Basic Rockcraft, Royal Robbins wrote the same thing: “To avoid getting in over our heads it is helpful to know the difficulty of routes ... [and] classification of routes helps us choose those consistent with our ability.” But Robbins added: “[T]ake the classification of climbs with a certain amount of salt, and avoid a bad aftertaste.” What Robbins meant by this, I gathered, was: don't trust the rating in a guidebook or you'll be sorry. Experienced climbers know from, well, experience that a 5.9 route in the guidebook might not actually be 5.9. |

Guidebook authors, trying to be helpful, sometimes include a narrative attempting to explain how the rating system works and how to tell the difference between, say, Class 4 and Class 5 climbing, and the subtle difference between a route rated 5.9 and a route rated 5.10.

Here’s what Beckey wrote on the subject in his 1965 guide: "The classification of a route will be class 4 or 5 if it is a free or non-aid route. Class 5, where pitons or bolts are suggested for protection, will usually be followed by a decimal… Most climbers will begin using pitons for protection at 5.0. An easy class 5 climb, for a competent rock climber, will be rated at 5.0 or 5.1. Difficulty increases to 5.9, which is a climb of exceptional severity, with 5.10 being the ultimate difficulty possible."

Here’s what Beckey wrote on the subject in his 1965 guide: "The classification of a route will be class 4 or 5 if it is a free or non-aid route. Class 5, where pitons or bolts are suggested for protection, will usually be followed by a decimal… Most climbers will begin using pitons for protection at 5.0. An easy class 5 climb, for a competent rock climber, will be rated at 5.0 or 5.1. Difficulty increases to 5.9, which is a climb of exceptional severity, with 5.10 being the ultimate difficulty possible."

|

I had no idea what any of this meant, but took it as gospel that if you could climb 5.0 or 5.1, you were a competent rock climber, and if you could climb 5.10 you were the best. Fred Beckey said so, and of course, I wanted to climb 5.10. Unfortunately, Beckey gave no clue as to how hard 5.10 actually was. I’d done a few rock climbs, but had no idea what a given rating really meant. How hard was 5.0? Could I climb something that hard? And how hard was 5.10 compared to 5.0? Would I ever be good enough to climb 5.10?

I found out soon enough. During the course, Brad and his guides led the class up an alpine rock route rated 5.0, which didn’t seem very hard, but I was chuffed. I was a “competent rock climber.” But later, against Brad’s admonitions, I tried to lead a 5.6 and backed off; it was way off the ground and scary. If I couldn’t climb 5.6, how could I ever climb 5.9, let alone 5.10? |

I did not, as modern climbers do, have the luxury of learning to climb on indoor gym walls where the routes are conveniently set, marked, and rated, and kids are cranking moves harder than anything anyone of my generation thought possible. No, I had to learn the hard way, by climbing actual routes, on lead, placing chocks for protection, slowly working my way up the grades, because that is simply how it was done. I didn’t have a problem with that, except for the slowly part. I was young and impatient. I wanted to climb 5.10 right now!

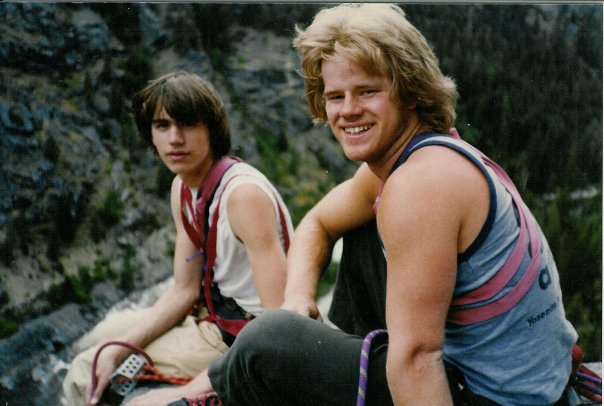

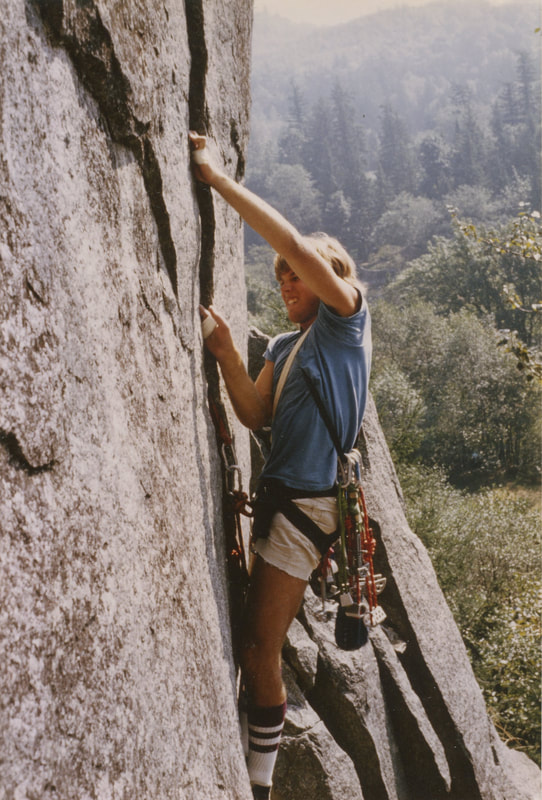

I fell in with a group of climbers my age who were also exploring their limits and starting to push them. One of those climbers was Mark Gunlogson, a high-school kid like me who had also taken Brad’s course. We’d go out every weekend and climb, and quickly worked our way through 5.6, 5.7, and 5.8, and before we knew it, we were trying and succeeding on routes rated 5.9, a level of “exceptional difficulty” according to Beckey. Heck, Royal Robbins climbed the Open Book route at Tahquitz Rock, the first 5.9 in America, when he was seventeen. Here we were, also seventeen and leading 5.9. We must be pretty good, we thought.

I fell in with a group of climbers my age who were also exploring their limits and starting to push them. One of those climbers was Mark Gunlogson, a high-school kid like me who had also taken Brad’s course. We’d go out every weekend and climb, and quickly worked our way through 5.6, 5.7, and 5.8, and before we knew it, we were trying and succeeding on routes rated 5.9, a level of “exceptional difficulty” according to Beckey. Heck, Royal Robbins climbed the Open Book route at Tahquitz Rock, the first 5.9 in America, when he was seventeen. Here we were, also seventeen and leading 5.9. We must be pretty good, we thought.

Duly impressed with ourselves, we promptly set off to lead our first 5.10s.

The route we chose for our first 5.10 lead was not a good choice. It involved twenty-five feet of thin, gear-protected 5.10c face climbing. Why we chose a 5.10c face instead of a nice 5.10a crack for our first 5.10 lead, I don’t remember, except the crux was close to the ground and seemed less scary. Not so. I got ten feet up the wall, was immediately gripped with fear, and bailed. Mark tried it and also backed off.

The route we chose for our first 5.10 lead was not a good choice. It involved twenty-five feet of thin, gear-protected 5.10c face climbing. Why we chose a 5.10c face instead of a nice 5.10a crack for our first 5.10 lead, I don’t remember, except the crux was close to the ground and seemed less scary. Not so. I got ten feet up the wall, was immediately gripped with fear, and bailed. Mark tried it and also backed off.

|

Undeterred, we tried another 5.10, a 5.10a hand crack this time, but it was even scarier, starting 100 feet off the ground.

Duly spanked, we decided we should climb some more 5.9s before trying another 5.10. This, we were sure, would give us the confidence to crush our first 5.10 lead next time. We were wrong, of course. We were both in our second year of climbing. We thought we knew what we were doing, but really had no clue. We had forgotten to add a grain of salt, and I was about to experience the bad aftertaste. There was a particular 5.9 pitch at Index that I’d followed once without falling, and it seemed like a sure thing to lead it. It was not. I made it halfway up the pitch, and was awkwardly face climbing instead of jamming up the steep flake like you’re supposed to do when I pumped out. Before I knew it, I was airborne, plummeting 30 feet before the rope jerked tight, just short of me smacking a big flake. It was my first leader fall, a real whipper with impressive airtime, held by a half-wedged #5 Hexcentric behind a wafer-thin flake. Undeterred, I rested and tried again, and struggled past the spot where I had fallen. Higher up, where a long layback flake led to a small roof, I rattled in a big Hex and reached directly past it, groping for a ledge and trying to mantel up. Before I knew it, I was flying again, another 30-footer held by another rattly chock. I rested on a ledge then finished the pitch on my next try via an easier variation that I should have taken in the first place, and dispatched the final finger crack—the crux of the route—without falling. I had pulled it off, but just barely. Taking two long falls had not helped my confidence at all. If I was going to climb 5.10, I would need more experience, and I was about to get it. |

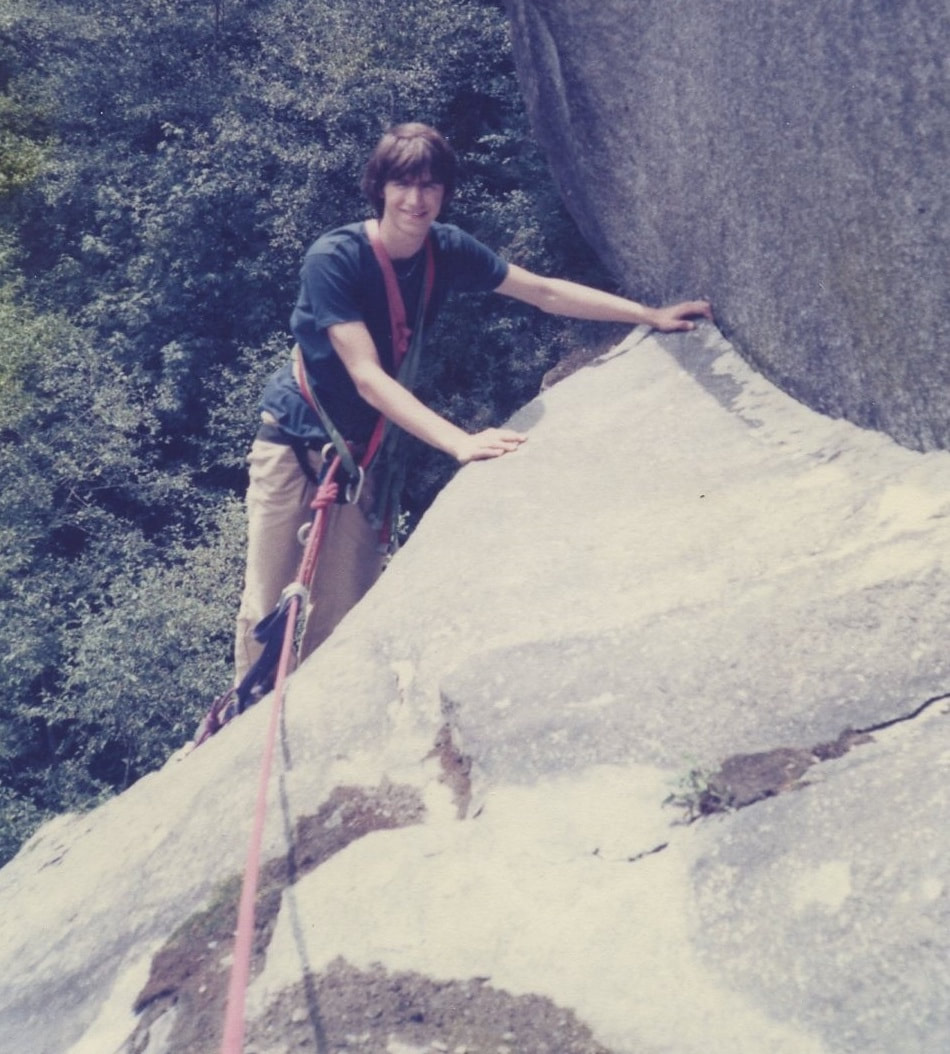

There was another 5.9 route I’d climbed before. It was 60-feet high with a crux 30 feet off the ground. I was sure I could run right up it like I had the first time; that would give me the confidence boost I needed to try again to climb 5.10. After my two whippers, I wanted to play it safe, so I placed a lot of protection. A vertical crack seemed to eat up wired Stoppers and I fed it liberally, slotting in a nut every three feet as I climbed and giving them a tug, making sure they were set before continuing on. Assured each piece was bombproof, and struck out boldly for the crux, a steep wall with a series of protruding knobs that required a short runout. No problem. I’d done it before, and my gear was good. I’d walk right up it; it would be a piece of cake.

I realized as I reached for the jug at the end of the crux that I’d botched the sequence. I was reaching with the wrong hand. No problem, I thought. I could make a little lunge for the knob. It was right there.

A second later, I was standing at the base of the wall wondering what had happened. I landed on my feet like a gymnast having executed a perfect dismount after a terrible high-bar routine. Mark was sitting on a boulder, holding the rope, looking at me in disbelief. On the dusty ground before me lay a tangle of red rope to which a half dozen wired stoppers remained clipped. Each piece had zippered out in succession. A moment before I had been 30 feet up the wall; a second later I was hitting the ground and rolling like a rag doll, out of control, at the mercy of dumb luck, which was on my side that day. Had I landed two feet to the left I would have struck a ledge with my feet, pitched backward and hit my head on a slab; two feet to the right I would have landed on the boulder. Instead, I landed feet-first on a patch of sandy soil and rolled backward down a short slab onto another patch of dirt. The impact had been negligible; I had barely felt it. I escaped with a couple of scrapes and a sore elbow.

Mark waited to make sure I was okay, then burst out laughing.

There’s nothing like a 30-foot ground fall to teach you what you need to know about climbing.

Brad had warned me that this would happen, but up until that moment it was all an abstraction, something that happened to other people, not me. Now I knew. It was a wake-up call. Climbing was hard; protection was unreliable; falling off was dangerous; hitting the ground hurt; it would be easy to die doing this. If I was going to keep climbing and have any expectation of surviving—if I didn’t want to be that person that Brad had told us would die climbing—I was going to have to make some changes.

Now I was afraid, not only of the objective hazards of climbing, but the subjective as well. I no longer trusted ropes, knots, carabiners, nuts, fixed pitons, or old bolts. I recognized that my enthusiasm and impatience to climb harder and harder routes were my own worst enemies. I went back to doing easier leads for a long time, rebuilding a base of confidence, climbing well within my limits, making certain that I didn’t push too hard, too high, too fast. I began to approach climbing with an overabundance of caution. I did some aid routes to learn how to place gear that would hold. I trained more assiduously to get stronger, bouldered obsessively, and top-roped progressively harder routes until I had them wired. I needed to be in control. If I could stay in control, I would not fall. If I did not fall, I would not die. At least in theory.

The trouble is, you can’t control everything in an environment where anything can happen. To climb at any level means pushing your luck to some degree, to risk the possibility of falling—especially when pushing your limits. You’re going to fall sometimes, and when you fall—even when roped up and clipped into gear—the risk of getting hurt or dying is very real. You have to take it deadly seriously because, if you don’t, you’re going to end up seriously dead.

I had not realized this before my ground fall. Climbing was fun, a lark. Nothing bad ever happened. Nothing really bad. But standing there stupidly on the ground, I felt lucky to have survived. Dumb luck alone, it seemed, had saved me. I resolved not to allow this to happen again.

But it did.

I was top-roping one day on a 40-foot boulder, belayed by a climber I’d just met. He seemed like an experienced climber and after a couple of hours of bouldering and doing easy climbs with him, I trusted him enough to belay me on a 5.10. I climbed it without falling, then decided to down-climb it instead of lowering and fell off. I didn’t fight to hang on. I was on a top-rope; the rope would come tight and hold me just like always.

It didn’t.

It went whizzing past as I fell and landed on a ledge. I managed to stop myself with my hands before I smacked my head or tumbled off into the boulders. I wasn’t hurt, but was pissed that my belayer had dropped me, and told him so. He apologized, then told me he was a recovering heroin addict and sometimes just “spaced.” I was lucky to walk away. Last year, another climber fell off the same route; he was leading and pulled all his gear. He died.

I realized as I reached for the jug at the end of the crux that I’d botched the sequence. I was reaching with the wrong hand. No problem, I thought. I could make a little lunge for the knob. It was right there.

A second later, I was standing at the base of the wall wondering what had happened. I landed on my feet like a gymnast having executed a perfect dismount after a terrible high-bar routine. Mark was sitting on a boulder, holding the rope, looking at me in disbelief. On the dusty ground before me lay a tangle of red rope to which a half dozen wired stoppers remained clipped. Each piece had zippered out in succession. A moment before I had been 30 feet up the wall; a second later I was hitting the ground and rolling like a rag doll, out of control, at the mercy of dumb luck, which was on my side that day. Had I landed two feet to the left I would have struck a ledge with my feet, pitched backward and hit my head on a slab; two feet to the right I would have landed on the boulder. Instead, I landed feet-first on a patch of sandy soil and rolled backward down a short slab onto another patch of dirt. The impact had been negligible; I had barely felt it. I escaped with a couple of scrapes and a sore elbow.

Mark waited to make sure I was okay, then burst out laughing.

There’s nothing like a 30-foot ground fall to teach you what you need to know about climbing.

Brad had warned me that this would happen, but up until that moment it was all an abstraction, something that happened to other people, not me. Now I knew. It was a wake-up call. Climbing was hard; protection was unreliable; falling off was dangerous; hitting the ground hurt; it would be easy to die doing this. If I was going to keep climbing and have any expectation of surviving—if I didn’t want to be that person that Brad had told us would die climbing—I was going to have to make some changes.

Now I was afraid, not only of the objective hazards of climbing, but the subjective as well. I no longer trusted ropes, knots, carabiners, nuts, fixed pitons, or old bolts. I recognized that my enthusiasm and impatience to climb harder and harder routes were my own worst enemies. I went back to doing easier leads for a long time, rebuilding a base of confidence, climbing well within my limits, making certain that I didn’t push too hard, too high, too fast. I began to approach climbing with an overabundance of caution. I did some aid routes to learn how to place gear that would hold. I trained more assiduously to get stronger, bouldered obsessively, and top-roped progressively harder routes until I had them wired. I needed to be in control. If I could stay in control, I would not fall. If I did not fall, I would not die. At least in theory.

The trouble is, you can’t control everything in an environment where anything can happen. To climb at any level means pushing your luck to some degree, to risk the possibility of falling—especially when pushing your limits. You’re going to fall sometimes, and when you fall—even when roped up and clipped into gear—the risk of getting hurt or dying is very real. You have to take it deadly seriously because, if you don’t, you’re going to end up seriously dead.

I had not realized this before my ground fall. Climbing was fun, a lark. Nothing bad ever happened. Nothing really bad. But standing there stupidly on the ground, I felt lucky to have survived. Dumb luck alone, it seemed, had saved me. I resolved not to allow this to happen again.

But it did.

I was top-roping one day on a 40-foot boulder, belayed by a climber I’d just met. He seemed like an experienced climber and after a couple of hours of bouldering and doing easy climbs with him, I trusted him enough to belay me on a 5.10. I climbed it without falling, then decided to down-climb it instead of lowering and fell off. I didn’t fight to hang on. I was on a top-rope; the rope would come tight and hold me just like always.

It didn’t.

It went whizzing past as I fell and landed on a ledge. I managed to stop myself with my hands before I smacked my head or tumbled off into the boulders. I wasn’t hurt, but was pissed that my belayer had dropped me, and told him so. He apologized, then told me he was a recovering heroin addict and sometimes just “spaced.” I was lucky to walk away. Last year, another climber fell off the same route; he was leading and pulled all his gear. He died.

|

Finding the right balance between climbing hard and controlling risk is not easy, but for me the lessons were clear: Train hard. Stay in control, mentally and physically. Know your limits. Know how to use your gear properly. Choose routes carefully to minimize unnecessary risk. Climb with people who are competent and have your trust. Learn from your mistakes and those of others. And above all, don’t let go easily; fight to avoid falling. I knew that I should not have given up so easily; I should have tried to hang on and avoid falling instead of assuming my gear would hold or my belayer would hold me.

If you’re not falling, you’re not trying, as the saying goes. And for most climbers, falling is part of the game. But a lot of climbers don’t try not to fall; they get to a hard move, get pumped or get scared, and just let go, like I did, assuming their protection will hold and their belayer will catch them. And they always do. Every time. But I know from experience they don’t always. Sometimes your gear pulls; sometimes a bolt breaks; sometimes your rope gets cut; sometimes you forget to finish your tie-in knot; sometimes your belayer fucks up and drops you; sometimes you hit the ground. I survived my third year of climbing and eventually managed to lead my first 5.10—without falling off and hitting the ground this time. If Brad Bradley was right, I would survive the rest of them, although I don’t take it for granted. Climbing is still dangerous; you never know. Still, most of my near-death experiences in climbing happened during my first three years, and I learned from them, so I think he was right. He was right about everything, even about tying knots one-handed in the shower. |

A few years back I was leading a 5.11 sport climb and had one of those things happen. You know, like what happened to Lynn Hill in 1989 when she fell 20 meters and hit the ground. She’d just led a sport route at Buoux without falls, clipped the anchors, and leaned back, expecting to be lowered off, and inexplicably started falling. In hindsight, she realized she’d been distracted, chatting with somebody as she was tying in, and hadn’t finished her knot. That’s exactly what I did. I’d been chatting with my partner, got distracted, and didn’t double check my knot. But 50 feet off the ground, just about to start up the crux, I checked it, just to be sure, and there it was, only half tied. No problem, I thought. I’ve got this. I held on with one hand and finished the knot. All those times I’d practiced tying knots one-handed in a cold shower had finally paid off.

“You are the most important piece of safety equipment you bring on any climb,” Brad had taught us. He was right.

He was right about everything.

“You are the most important piece of safety equipment you bring on any climb,” Brad had taught us. He was right.

He was right about everything.

Jeff Smoot is the author of numerous climbing-related books including Hangdog Days: Conflict, Change, and the Race for 5.14 , which was a finalist for several awards including the 2020 Washington State Book Awards.

His upcoming book All and Nothing: Inside Free Soloing (Mountaineers Books, Fall 2022) explores the psychology of risk-taking to find out what drives people so perilously close to the void.

Check out Jeff's full bio to see additional book he has published.

His upcoming book All and Nothing: Inside Free Soloing (Mountaineers Books, Fall 2022) explores the psychology of risk-taking to find out what drives people so perilously close to the void.

Check out Jeff's full bio to see additional book he has published.