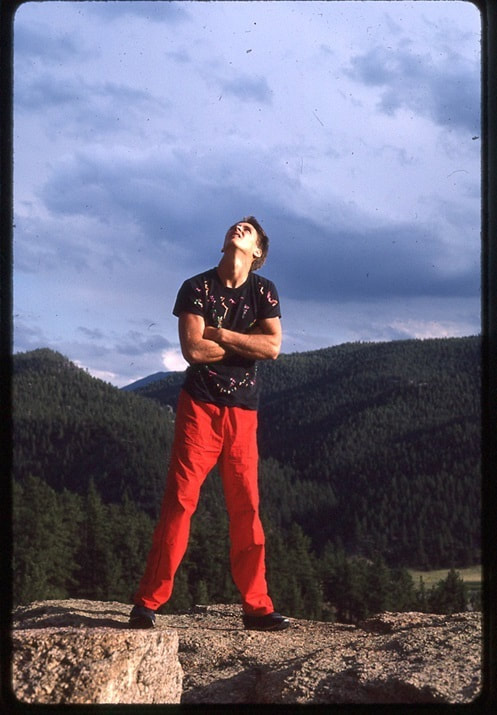

ABOVE: On the road with Hugh Herr. Who can resist that smile? (Photo Credit Jeff Smoot.)

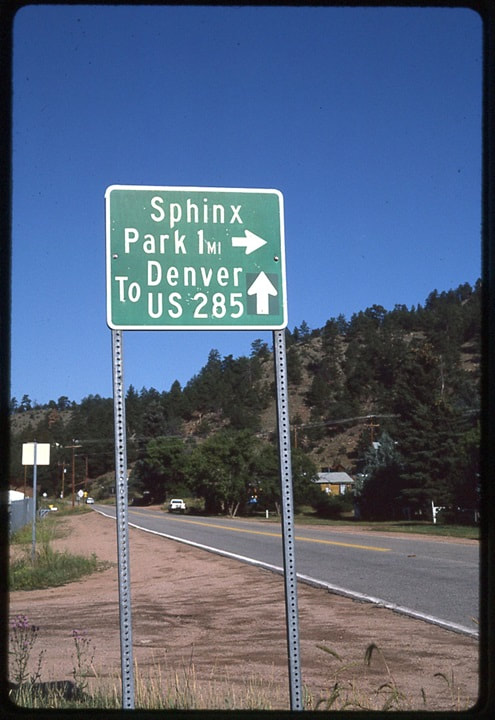

Hugh and I left Aspen, Colorado in the morning and arrived in Pine by mid-afternoon. We had come so Hugh could try to climb Sphinx Crack before we headed into Boulder. We weren’t in any particular hurry, and had told our friends we’d arrive in town in a couple of days, but a storm was blowing in. No worries, Hugh said. We could stay at Christian Griffith’s house whenever we got there, so even if we arrived a couple of days early, we’d have a place to crash. I didn't know Christian personally, but was not one to reject his kind offer of a couch to sleep on. It would certainly beat sleeping in dirt and gravel on the side of the road or, if it rained, inside the car listening to Hugh snore.

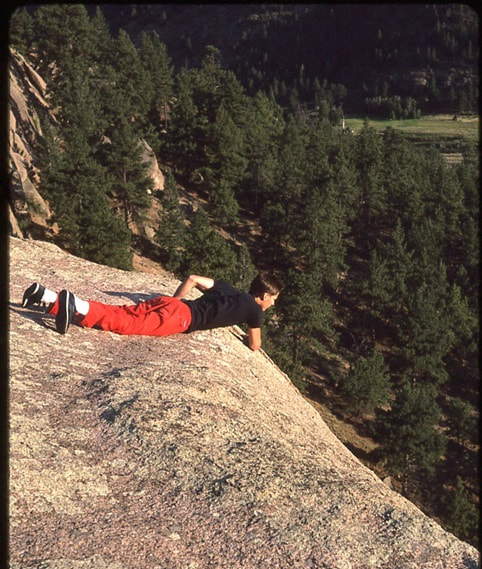

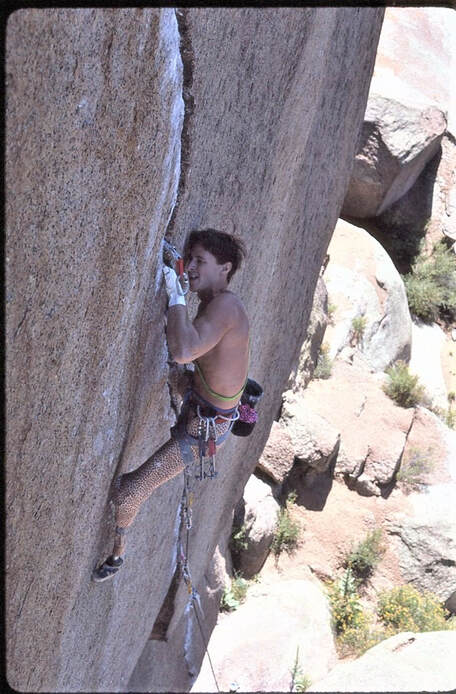

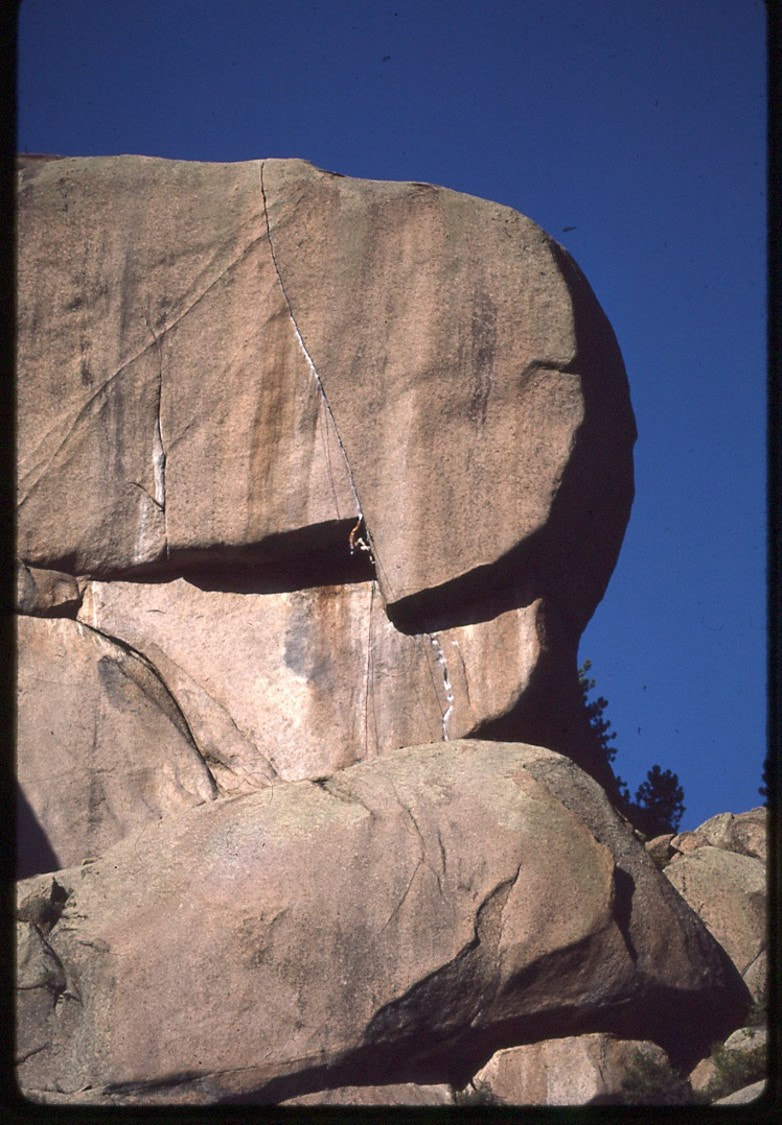

It was sunny when we arrived in Pine, and we hiked up to the base of Sphinx Rock then scrambled to the top so Hugh could get a good look at the crack. He crawled to the edge and peered down the overhanging wall, then crawled back carefully, stood up, and looked at the sky. The wind was picking up and the clouds threatened rain. We could hear thunder in the distance. It was time to get going if we wanted to beat the storm.

It was sunny when we arrived in Pine, and we hiked up to the base of Sphinx Rock then scrambled to the top so Hugh could get a good look at the crack. He crawled to the edge and peered down the overhanging wall, then crawled back carefully, stood up, and looked at the sky. The wind was picking up and the clouds threatened rain. We could hear thunder in the distance. It was time to get going if we wanted to beat the storm.

As we turned east onto Highway 285 and started down the winding road toward Denver, it began to rain. With each mile the sky grew darker and the rain pounded harder. A big storm had blown in off the plains and we were driving right into the maw of it. Lightning flashed and thunder roared, again and again, insistently as if delivering a message: Go back, fools! Do not dare to enter the Valley of the Gods! I ignored the warnings and drove silently toward Boulder, loathing my fate. The gods were punishing me, I imagined, probably for the bad thoughts I was having about Hugh.

|

At first I’d been excited to go on a road trip with Hugh, but the honeymoon was over. I didn’t know what it was, but I wasn’t having fun anymore. It wasn’t Hugh’s fault; I was just tired of being on the road, flailing on all the hard routes Hugh wanted to climb. And although it had sounded fun to go to Boulder and do some of the classic climbs there, I didn’t want to go there anymore. I wanted to go back to Aspen.

Hugh and I had stopped in Aspen on the way to Boulder so Hugh could try to climb an overhanging thin crack that John Steiger thought Hugh might be able to pull off. We hiked up one morning and gave it a shot, but it was ridiculous, so thin and overhanging that it would take weeks of effort to free climb, if it was even possible. Hugh decided to save his skin for Sphinx Crack. “What’s there to do around here?” Hugh asked John as he drove us back into town. John had been a great host. He let us stay at the apartment he shared with two other people, took us to a screening of Bring on the Night at the Aspen Film Festival the night before, and took time off from work to go climbing with us. “The ballet is in town,” John said, imagining Hugh and I could afford to see the ballet, “but they don’t perform until Friday night.” |

“What else?” Hugh asked.

“Well,” said John, “you could go to the disco…”

As we walked into the discotheque that night, you wouldn’t have known we were two dirtbag rock climbers living out of a car. We’d both packed a pair of decent pants, though, and, thanks to John’s hospitality, were able to shower before our big night out. Hugh had to borrow one of my shirts, and I must say it fit him handsomely.

We sat down at a table and ordered beers, and before we had finished them we were joined by two lovely young women who, it turned out, were ballerinas enjoying a night on the town. One thing led to another, and before you knew it, Hugh was out on the dance floor with one of the girls. He was no John Travolta, but he didn’t have to be. All he had to do was flash that smile of his to melt that girl’s heart.

I somehow managed to wrangle a date with the other ballerina. While John took Hugh climbing the next day, we took a leisurely stroll through downtown Aspen, toured a few art galleries, had lunch al fresco underneath a big Cinzano umbrella, and then walked to hotel in time for her to get ready for an afternoon rehearsal.

“How long are you staying in Aspen?” she asked me.

“We’re leaving in the morning,” I told her.

“That’s too bad,” she said.

“Well,” said John, “you could go to the disco…”

As we walked into the discotheque that night, you wouldn’t have known we were two dirtbag rock climbers living out of a car. We’d both packed a pair of decent pants, though, and, thanks to John’s hospitality, were able to shower before our big night out. Hugh had to borrow one of my shirts, and I must say it fit him handsomely.

We sat down at a table and ordered beers, and before we had finished them we were joined by two lovely young women who, it turned out, were ballerinas enjoying a night on the town. One thing led to another, and before you knew it, Hugh was out on the dance floor with one of the girls. He was no John Travolta, but he didn’t have to be. All he had to do was flash that smile of his to melt that girl’s heart.

I somehow managed to wrangle a date with the other ballerina. While John took Hugh climbing the next day, we took a leisurely stroll through downtown Aspen, toured a few art galleries, had lunch al fresco underneath a big Cinzano umbrella, and then walked to hotel in time for her to get ready for an afternoon rehearsal.

“How long are you staying in Aspen?” she asked me.

“We’re leaving in the morning,” I told her.

“That’s too bad,” she said.

|

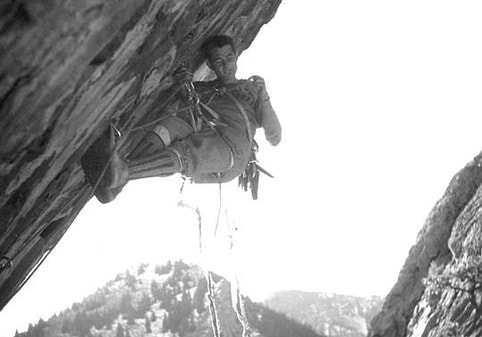

If Hugh'd had any kind of success on that thin crack the day before, we might have hung around in Aspen for a week or two while he tried to climb it. Someone eventually did free it and it’s rated 5.14; if Hugh had tried hard, he could have established a 5.14 route before J.B. Tribout had even arrived at Smith Rock that fall. But Hugh had friends to meet in Boulder and was starting classes at M.I.T. soon and was impatient to get there.

But now, those three words—“That’s too bad”—made me wish Hugh could change his plans and blow off his friends for a little while. And so it is understandable, I think, that as I drove through the storm on the way to Boulder, I was fantasizing about dropping Hugh off at Christian Griffith’s house and heading straight back to Aspen. Just then, a bolt of lightning flashed and thunder detonated instantaneously, rattling the car and shocking me back to reality. I looked over at Hugh. He had fallen asleep. I followed the main highway into Denver and stopped at a 7-Eleven store on the outskirts so Hugh could use the pay phone to call ahead to let Christian know we would be dropping in. As our luck would have it, he wasn’t home, and his housemate did not know where he was or when he would be back. “What should we do?” Hugh asked. I shrugged my shoulders. |

“Let’s drive to Boulder,” Hugh said. “He’ll probably be home by the time we get there.”

We arrived in Boulder a half hour later and promptly got lost trying to find Christian's house, but eventually found our way there. It was easy to spot it; it was the only house on the block with a Bachar ladder in the front yard.

Christian was still not home, so we waited on the couch while his housemate eyed us suspiciously. After a while, we decided to leave to get something to eat and find a pay phone to call George Bracksieck. George had offered to let us stay at his house, so I hoped he might be home. If nothing else, we could visit with George until Christian got home. We found a pay phone next to a Laundromat. I looked up George's number and dialed. A recorded message answered. I hung up.

“What now?” Hugh asked.

“Beats me,” I said. “Call and see if Christian is back?”

Hugh tried calling Christian again, but he was still not home, and his housemate now seemed annoyed that we were pestering him. I called George again, but still no answer. There was a listing for another Bracksieck in the phone directory, though. I dialed the number, hopeful that it would be a relative who would know where George was and how I could reach him.

“Hello?” a man’s voice answered.

“Yes, hello,” I said. “I’m trying to get a hold of George Bracksieck. Is he a relative of yours?”

“Yes, yes,” the man said. “I’m his father. Who is this?”

“It’s Jeff Smoot,” I said, giving Hugh a thumbs up. “I’m a contributor to his magazine. George is expecting me in town but I’m a couple of days early. I was trying to get a hold of him but he’s out somewhere. You wouldn’t happen to know where he is, would you?”

“I do. He’s at a benefit dinner tonight. He’ll be out late, I think. You should call him tomorrow.”

“Okay, I will,” I said, giving Hugh a thumbs down. “Let him know I called, would you?”

“I certainly will. What was your name again?”

Hugh tried Christian's house one more time, and this time no one answered. It was threatening to rain in Boulder now, so we had to either find a place to spend the night or get out of there before the storm hit us again. We talked about finding an out-of-the-way place to stealth camp in the car, but had been warned that the Boulder police would arrest us or at least run us out of town if we tried. One might get away with sleeping in the boulders behind Camp 4, we were assured, but not in Boulder, Colorado.

“Who else can we call?” I wondered, flipping pages in the phone book.

“How about Layton Kor?” Hugh said. I had to laugh. Kor was a legend, pioneer of many of the most classic routes in Colorado, and one of the icons of American rock climbing. The idea of cold calling Layton Kor to ask if we could crash at his place was outrageous. It would be like arriving in Carmel, California, one evening and ringing up Clint Eastwood to see about setting up a tent on his lawn.

We arrived in Boulder a half hour later and promptly got lost trying to find Christian's house, but eventually found our way there. It was easy to spot it; it was the only house on the block with a Bachar ladder in the front yard.

Christian was still not home, so we waited on the couch while his housemate eyed us suspiciously. After a while, we decided to leave to get something to eat and find a pay phone to call George Bracksieck. George had offered to let us stay at his house, so I hoped he might be home. If nothing else, we could visit with George until Christian got home. We found a pay phone next to a Laundromat. I looked up George's number and dialed. A recorded message answered. I hung up.

“What now?” Hugh asked.

“Beats me,” I said. “Call and see if Christian is back?”

Hugh tried calling Christian again, but he was still not home, and his housemate now seemed annoyed that we were pestering him. I called George again, but still no answer. There was a listing for another Bracksieck in the phone directory, though. I dialed the number, hopeful that it would be a relative who would know where George was and how I could reach him.

“Hello?” a man’s voice answered.

“Yes, hello,” I said. “I’m trying to get a hold of George Bracksieck. Is he a relative of yours?”

“Yes, yes,” the man said. “I’m his father. Who is this?”

“It’s Jeff Smoot,” I said, giving Hugh a thumbs up. “I’m a contributor to his magazine. George is expecting me in town but I’m a couple of days early. I was trying to get a hold of him but he’s out somewhere. You wouldn’t happen to know where he is, would you?”

“I do. He’s at a benefit dinner tonight. He’ll be out late, I think. You should call him tomorrow.”

“Okay, I will,” I said, giving Hugh a thumbs down. “Let him know I called, would you?”

“I certainly will. What was your name again?”

Hugh tried Christian's house one more time, and this time no one answered. It was threatening to rain in Boulder now, so we had to either find a place to spend the night or get out of there before the storm hit us again. We talked about finding an out-of-the-way place to stealth camp in the car, but had been warned that the Boulder police would arrest us or at least run us out of town if we tried. One might get away with sleeping in the boulders behind Camp 4, we were assured, but not in Boulder, Colorado.

“Who else can we call?” I wondered, flipping pages in the phone book.

“How about Layton Kor?” Hugh said. I had to laugh. Kor was a legend, pioneer of many of the most classic routes in Colorado, and one of the icons of American rock climbing. The idea of cold calling Layton Kor to ask if we could crash at his place was outrageous. It would be like arriving in Carmel, California, one evening and ringing up Clint Eastwood to see about setting up a tent on his lawn.

“Yeah, sure,” I countered. “How about Jim Erickson.” Erickson was another Colorado climbing legend, who had pushed the limits of free climbing and free soloing during the 1970s, that Hugh and I had never met or even talked to.

“Hey, Jim,” Hugh said, pretending to have a phone conversation, “this is Hugh Herr. You don’t know me, but could I sleep on your sofa?”

Although we were both laughing hysterically because it was so absurd, really, this was not such an outrageous idea that we didn’t try to look up Layton Kor and Jim Erickson in the phone book. It was raining now, and would soon get dark, and we were becoming desperate to find a place to stay. And who knew? Maybe we would get a hold of one of them and they would be okay with us crashing at their place. It could happen.

We didn’t find Kor’s number, but Erickson was listed in the directory.

“I dare you to call him,” Hugh said, grinning.

“Sure,” I said. “What do we have to lose?”

I dialed Erickson’s number, hopeful he would answer but also relieved when he didn’t.

“Maybe we should call Pat Ament,” I suggested.

This was another absurd idea. Ament was another legend of Colorado climbing, pioneer of some of the earliest 5.11 routes in America. But I’d read that Ament was friends with Christian Griffith, so it made sense to call him looking for Christian. Who knew? Maybe he knew where Christian was. But even if he didn’t, it would be a perfect pretext to asking Ament if we might hang out at his house for a while, at least until Christian got home. For all we knew, Ament would be a perfectly gracious host, invite us in, feed us, regale us with stories, and let us set up camp in his living room or at least sleep in the car in his driveway. He might not, but at this point we had nothing to lose.

“Yeah!” Hugh said. “Let’s give him a call.”

Sure enough, Pat Ament was listed in the phone book. Hugh looked at me quizzically, and I looked back. We busted out laughing again.

Since I'd tried calling Jim Erickson, it was Hugh's turn. He dialed Ament’s number but no one answered. Ament’s address was listed in the white pages, though, and his house was not far away according to the map in the phone book. It was starting to get dark, and we were running out of time.

I am not sure what made us think we could call a complete stranger and be welcomed to hang out at his place, let alone show up at his front door after dark on a Friday night, grinning stupidly, asking to intrude on his quiet evening. Perhaps we had faith that the climbing community is welcoming and inclusive and if you are a friend-of-a-friend passing through town on a climbing trip and need a place to crash, a fellow climber will be more than happy to accommodate you.

Pat Ament, it turned out, was not. At least, that’s what the events to unfold that evening led us to believe.

We soon arrived at the address, the downstairs unit of a two-story wood-framed house. We knocked politely on the screen door a few times. When that didn't get a response, we began knocking a little less politely on the door frame. The house remained dark. No one answered after several tries.

“Oh, well,” Hugh said. “We tried.”

We turned to leave and were walking away when we heard a shuffling inside the house. A light went on, the latch clicked, and the door opened an inch or two. A man in his night clothes stood there, looking out at us quizzically as if wondering what we were selling or which religion we wanted him to convert to.

“Can I help you?” he asked.

“Hi,” Hugh said. “Are you Pat Ament?”

“Yes," the man said warily, "Who are you?”

“I’m Hugh, and this is Jeff," Hugh continued. "Sorry to bother you. We’re climbers from out of town. We were supposed to stay at Christian Griffith’s house tonight, but we can’t find him. We were hoping maybe you might know where he is.”

“Sorry, I don’t know.”

“Oh,” Hugh said, flashing that smile of his. “So, we’re hoping to find a place to stay for a little while until he gets home, or—”

There was a long pause. The man stared blankly at us through the crack in the door.

“I’m sorry,” he finally said. “I don’t know you. You can’t stay here.”

“Can we maybe just park in your driveway and—”

“No.”

“Okay. Do you know anywhere we could stay?”

“No. I’m sorry.”

“Well,” Hugh said politely. “Thank you anyway.”

The man closed the door, latched the latch, and turned off the light. We would have to fend for ourselves.

We hadn’t really expected Pat Ament to invite us in, any more than Layton Kor or Jim Erickson would have. Who were we anyway? Just a couple of kids trying to hustle up a place to stay. And honestly, if a couple of strangers showed up at my door out of the blue after I’d settled in for the night, I’d probably tell them no, sorry, you can’t stay here, and shut the door.

But that would never happen now; now you can post a message asking if any of your friends knew anybody who could put you up for the night, or make a few calls on your cell phone, and you’d be flooded with invitations in no time. Back then, though, if you showed up uninvited in a strange town, you had to find a pay phone and hope you had a slug of dimes. Hugh and I had been brash and overly optimistic; we knew it was audacious, rude even, to knock on a famous climber’s door and ask to impose on him so shamelessly. Even so, for a second there, in that moment when the man had come to the door and opened it a crack, we thought we were going to pull it off.

“What now?” I asked, sitting in the driver’s seat, wondering where to go.

“I don’t know,” Hugh said. “Back where we came from, I guess.”

The thought of dropping Hugh at Christian Griffith’s house and driving back to Aspen occurred to me again, but I dismissed it. However misguided and hopeless our effort had been, it had, for the moment, made me want to hang out with Hugh a little while longer. We had come to climb. Those ballerinas would have to wait.

We tucked our tails between our legs and drove all the way back to Pine and slept in the car along the forest service road across the creek from Sphinx Rock. We didn’t say a word to each other the whole way there. The storm was still raging as we climbed up Highway 285 back toward Pine. But then, miraculously, the rain stopped as we arrived in Pine and turned up the road to Sphinx Rock. By the time we pulled off into the same turnout we had left hours earlier, the storm clouds had passed, the sky had cleared, and we could see the stars.

“That was stupid,” I said as I threw my pad and sleeping bag out on the gravel. “We should have stayed here.”

“Yeah,” Hugh said, grinning. “But it sure was nice to meet Pat Ament.”

Sure enough, Pat Ament was listed in the phone book. Hugh looked at me quizzically, and I looked back. We busted out laughing again.

Since I'd tried calling Jim Erickson, it was Hugh's turn. He dialed Ament’s number but no one answered. Ament’s address was listed in the white pages, though, and his house was not far away according to the map in the phone book. It was starting to get dark, and we were running out of time.

I am not sure what made us think we could call a complete stranger and be welcomed to hang out at his place, let alone show up at his front door after dark on a Friday night, grinning stupidly, asking to intrude on his quiet evening. Perhaps we had faith that the climbing community is welcoming and inclusive and if you are a friend-of-a-friend passing through town on a climbing trip and need a place to crash, a fellow climber will be more than happy to accommodate you.

Pat Ament, it turned out, was not. At least, that’s what the events to unfold that evening led us to believe.

We soon arrived at the address, the downstairs unit of a two-story wood-framed house. We knocked politely on the screen door a few times. When that didn't get a response, we began knocking a little less politely on the door frame. The house remained dark. No one answered after several tries.

“Oh, well,” Hugh said. “We tried.”

We turned to leave and were walking away when we heard a shuffling inside the house. A light went on, the latch clicked, and the door opened an inch or two. A man in his night clothes stood there, looking out at us quizzically as if wondering what we were selling or which religion we wanted him to convert to.

“Can I help you?” he asked.

“Hi,” Hugh said. “Are you Pat Ament?”

“Yes," the man said warily, "Who are you?”

“I’m Hugh, and this is Jeff," Hugh continued. "Sorry to bother you. We’re climbers from out of town. We were supposed to stay at Christian Griffith’s house tonight, but we can’t find him. We were hoping maybe you might know where he is.”

“Sorry, I don’t know.”

“Oh,” Hugh said, flashing that smile of his. “So, we’re hoping to find a place to stay for a little while until he gets home, or—”

There was a long pause. The man stared blankly at us through the crack in the door.

“I’m sorry,” he finally said. “I don’t know you. You can’t stay here.”

“Can we maybe just park in your driveway and—”

“No.”

“Okay. Do you know anywhere we could stay?”

“No. I’m sorry.”

“Well,” Hugh said politely. “Thank you anyway.”

The man closed the door, latched the latch, and turned off the light. We would have to fend for ourselves.

We hadn’t really expected Pat Ament to invite us in, any more than Layton Kor or Jim Erickson would have. Who were we anyway? Just a couple of kids trying to hustle up a place to stay. And honestly, if a couple of strangers showed up at my door out of the blue after I’d settled in for the night, I’d probably tell them no, sorry, you can’t stay here, and shut the door.

But that would never happen now; now you can post a message asking if any of your friends knew anybody who could put you up for the night, or make a few calls on your cell phone, and you’d be flooded with invitations in no time. Back then, though, if you showed up uninvited in a strange town, you had to find a pay phone and hope you had a slug of dimes. Hugh and I had been brash and overly optimistic; we knew it was audacious, rude even, to knock on a famous climber’s door and ask to impose on him so shamelessly. Even so, for a second there, in that moment when the man had come to the door and opened it a crack, we thought we were going to pull it off.

“What now?” I asked, sitting in the driver’s seat, wondering where to go.

“I don’t know,” Hugh said. “Back where we came from, I guess.”

The thought of dropping Hugh at Christian Griffith’s house and driving back to Aspen occurred to me again, but I dismissed it. However misguided and hopeless our effort had been, it had, for the moment, made me want to hang out with Hugh a little while longer. We had come to climb. Those ballerinas would have to wait.

We tucked our tails between our legs and drove all the way back to Pine and slept in the car along the forest service road across the creek from Sphinx Rock. We didn’t say a word to each other the whole way there. The storm was still raging as we climbed up Highway 285 back toward Pine. But then, miraculously, the rain stopped as we arrived in Pine and turned up the road to Sphinx Rock. By the time we pulled off into the same turnout we had left hours earlier, the storm clouds had passed, the sky had cleared, and we could see the stars.

“That was stupid,” I said as I threw my pad and sleeping bag out on the gravel. “We should have stayed here.”

“Yeah,” Hugh said, grinning. “But it sure was nice to meet Pat Ament.”

Postscript to “Calling Pat Ament”

I recently befriended Pat Ament on Facebook, and soon got a message from him about my article. He didn’t say he didn’t like it, but did take issue with my portrayal of him as being standoffish and unhelpful, things he definitely was not.

“I am well known for opening my door to total strangers, letting people sleep on my couch or floor or make themselves at home in my backyard,” he wrote. “I have had to do the same when I traveled around in younger, adventurous days.”

In my story, a man in pajamas answers the door after dark, opens the door a crack, and peeks out at me and Hugh - all things Pat says he would never do. “l never wore pajamas, would never peek out through a cracked door, and would not turn away fellow climbers,” he said. Although the place I describe in the story - a downstairs, garden-level apartment with a backyard - is where he lived for a time, he expressed doubt it was him that we talked to that night.

“I moved out of that [apartment] in fall 1984,” he told me. “I know l was evicted for letting a professor stay there that month l was in Yosemite. Then l went back to school at C.U. that fall of 1984. After that, for a semester, l was in a second story apartment about where the health food store is on Broadway at Arapahoe, then in another apartment the next semester on Mapleton (west of 9th) in north Boulder."

“But l would never have felt imposed upon,” he assured me. “I would ride the freight trains from Denver to Sacramento, hitch hike to Berkeley, and show up with a soot-black face at someone's door at some strange hour.... So, l knew what it was like to need a place to crash.”

I remember distinctly that the person who answered the door that night responded affirmatively when we asked if he was Pat Ament, and I swear he looked like the photos of Pat I'd seen, and so believed it was indeed Pat Ament for the past many years. But Hugh and I visited Boulder in 1986, two years after Ament moved out of the apartment. If he didn’t even live there, it couldn't have been him.

So apparently, one night 35-years ago, a confused man in Boulder, Colorado, answered his door to find two strange young men knocking, inquiring if they could crash on his couch or, failing that, sleep on his lawn. No wonder he told us no. But now we know: that man was not Pat Ament. I apologize to Pat for my error, and, seeing that I have not in fact ever met him in person, hope I may someday. He’s invited to crash at my place if he’s ever in town.

“I am well known for opening my door to total strangers, letting people sleep on my couch or floor or make themselves at home in my backyard,” he wrote. “I have had to do the same when I traveled around in younger, adventurous days.”

In my story, a man in pajamas answers the door after dark, opens the door a crack, and peeks out at me and Hugh - all things Pat says he would never do. “l never wore pajamas, would never peek out through a cracked door, and would not turn away fellow climbers,” he said. Although the place I describe in the story - a downstairs, garden-level apartment with a backyard - is where he lived for a time, he expressed doubt it was him that we talked to that night.

“I moved out of that [apartment] in fall 1984,” he told me. “I know l was evicted for letting a professor stay there that month l was in Yosemite. Then l went back to school at C.U. that fall of 1984. After that, for a semester, l was in a second story apartment about where the health food store is on Broadway at Arapahoe, then in another apartment the next semester on Mapleton (west of 9th) in north Boulder."

“But l would never have felt imposed upon,” he assured me. “I would ride the freight trains from Denver to Sacramento, hitch hike to Berkeley, and show up with a soot-black face at someone's door at some strange hour.... So, l knew what it was like to need a place to crash.”

I remember distinctly that the person who answered the door that night responded affirmatively when we asked if he was Pat Ament, and I swear he looked like the photos of Pat I'd seen, and so believed it was indeed Pat Ament for the past many years. But Hugh and I visited Boulder in 1986, two years after Ament moved out of the apartment. If he didn’t even live there, it couldn't have been him.

So apparently, one night 35-years ago, a confused man in Boulder, Colorado, answered his door to find two strange young men knocking, inquiring if they could crash on his couch or, failing that, sleep on his lawn. No wonder he told us no. But now we know: that man was not Pat Ament. I apologize to Pat for my error, and, seeing that I have not in fact ever met him in person, hope I may someday. He’s invited to crash at my place if he’s ever in town.

For more on Hugh Herr (a double amputee climber who was on the hunt for the first 5.14) check out The Tape Job by Jeff Smoot.