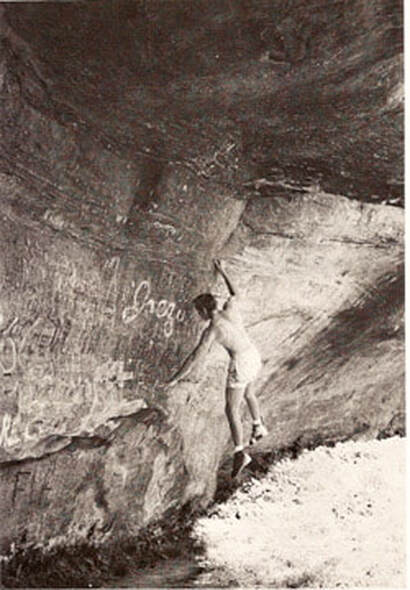

Above: The bouldering spray wall - a great application of the Graham Scale (read on to learn more...) (Photo Credit: Vertical World)

Learn to mistrust rating systems and pity those who are slaves to them.” |

This voice-over video by @Climberisms Dylan Taylor of John Sherman (aka. "The Verm") fits the bill...

|

We can get carried away with rating scales and use them in ways not intended by their creators.

When I started climbing, there were two rating options for bouldering: doing your best to apply the Yosemite Decimal System (YDS) to boulder problems or using the Gill System, neither of which was entirely satisfactory. These rating systems have since been supplanted by the V-Scale and the Font Scale. Although I like John Sherman, the creator of the V-Scale (the “V” stands for “Vermin,” Sherman’s nickname, although I call it the “Sherman Scale” because I refuse to conform), I dislike his rating system - in fact, I dislike all of them except the Graham Scale. What is the Graham Scale you ask? I'll get to that in a minute. First a little history in the convoluted art of bouldering ratings.

Rating is tricky business, especially when it comes to boulder problems.

When I started climbing, there were two rating options for bouldering: doing your best to apply the Yosemite Decimal System (YDS) to boulder problems or using the Gill System, neither of which was entirely satisfactory. These rating systems have since been supplanted by the V-Scale and the Font Scale. Although I like John Sherman, the creator of the V-Scale (the “V” stands for “Vermin,” Sherman’s nickname, although I call it the “Sherman Scale” because I refuse to conform), I dislike his rating system - in fact, I dislike all of them except the Graham Scale. What is the Graham Scale you ask? I'll get to that in a minute. First a little history in the convoluted art of bouldering ratings.

Rating is tricky business, especially when it comes to boulder problems.

|

Gill, one of the earliest American climbers to focus on bouldering as an end unto itself, viewed it as a distinct pursuit that started approximately where rock climbing ended difficulty-wise. The Gill System was as simple as it was enigmatic, with only three ratings —“B1,” “B2,” and “B3”— to define a broad scope of free-climbing difficulty. Under the Gill System, a “B1” problem included moves about as hard as the most-difficult route of the day; at the time Gill developed his system, 5.10 was at the top of the scale, so “B1” started approximately there. A “B2” problem was “harder than B1,” so hard that only the best climbers could achieve it. A “B3” problem was so hard it had only been done once; if repeated, it became “B2,” which resulted in a glut of “B2” and “B2+” problems as climbers improved and repeated the hardest problems.

Gill intended his rating system to “[challenge] climbers to improve their technical skills to the point they were capable of 'bouldering level' difficulty,” he wrote. Roughly translated, not everybody could call themselves a “boulderer”; you earned it by improving your ability to the level of being able to do a “boulder problem” which was by definition at least “B1” in difficulty. Although Gill intended his rating system as a challenge, it was not always taken that way. Some climbers wanted more instant gratification, a number that would validate their progress (or prowess as the case might be), not only to test their technical skills, but also to compare them with the skills of other climbers, to see who was “better.” |

Of course, an existing rating system, the YDS, provided such a basis for comparison. Back when I got into rock climbing, the best among us were climbing 5.12; a few 5.13 routes were rumored to have been climbed, but were shrouded in mystery and often referred to as being “5.12+” in difficulty. Those numbers set a high bar that ambitious young climbers like me aspired to clear someday.

Part of the process, then as now, was pushing my limits on the boulders. Knowing a particular boulder problem was 5.11 in difficulty allowed me to build confidence to eventually lead 5.11 routes and onward up the scale. Gill rejected the YDS because he was trying to define bouldering as distinct from rock climbing, a higher art if you will, that deserved a unique measure of comparison.

Part of the process, then as now, was pushing my limits on the boulders. Knowing a particular boulder problem was 5.11 in difficulty allowed me to build confidence to eventually lead 5.11 routes and onward up the scale. Gill rejected the YDS because he was trying to define bouldering as distinct from rock climbing, a higher art if you will, that deserved a unique measure of comparison.

|

To resolve this conflict, some climbers combined the Gill System and YDS, putting a “B” in front of the numerical rating (e.g., “B5.12” or “B12”), which Sherman considered “heresy.” Like Gill, Sherman rejected the YDS for rating boulder route difficulty because he felt it was best used for accumulated difficulty on longer rock climbs, including the “pump factor,” not the sheer technical difficulty of a typical single move or short sequence. Enter the V-scale. All Sherman really did was stick a “V” in front of a number instead of a “B,” creating his own heretical rating system which he unleashed on the bouldering world in his original Hueco Tanks bouldering guide. For whatever reason, which Sherman himself doesn’t quite get, the V-Scale caught on.

Inherently under each system, easier routes on boulders were deemed to be not “problems” worthy of a rating. In that respect, both the Gill System and the V-Scale, are somewhat elitist and dismissive of climbers for whom even an entry-level boulder problem is too difficult, giving them little more than a feeling of inferiority when they can’t even climb a “B1” or “V1”— the easiest numerical value on the respective scales. The Fontainebleau (“Font”) Scale is similar to the V-scale and also propagates the "too easy" elitism. The Font Scale is just numbers until it reaches 6 and then the letters A, B, and C are added in before progressing to the next number. Both the V and Font scales are open ended, with the numbers getting larger as the difficulty increases, but the Font scale begins at 3 because anything below 3 is considered too easy and not bouldering. The Font Scale hasn’t caught on in the U.S., where the Sherman Scale is king. Personally, I’m not sure the Sherman Scale is an improvement over the YDS, since both rating systems are open-ended and accomplish the same thing. In its favor, the YDS includes easier problems considered “too easy” to register on the Sherman Scale except condescendingly as “V0” or the lowly “VB” (or even worse “V-Fun!”). |

The YDS certainly seems more inclusive than the other scales in that respect since it starts at 5.0 (super easy) and progresses gradually up to 5.15d (too hard for any but the most beastly among us), but is it appropriate for rating boulder problems which, by their nature, are more difficult on a move-by-move basis than your average climbing route, or at least, according to the founders of the rating systems, should be?

It turns out Gill and Sherman both claim to dislike subjective rating systems, at least for boulder problems. Gill wondered about the true nature of climbing difficulty, asking “Can there really be a uniform code describing it? Does it exist in some abstract, objective way?” He recognized that boulderers would ideally use a rating system to measure their improvement over time, but considered any system that sought to objectively define difficulty to be inconsistent at best, overly competitive at worst.

As for Sherman, when he turned in the first draft of his bouldering guide, it did not include ratings; his publisher insisted that a rating system be included, fearing a guidebook without ratings was doomed to failure, so he unleashed his V-Scale on us and, in doing so, as he wrote in his article, “To V or Not to V,” brought “the joy of number chasing to bouldering.”

Some old-school climbers still prefer the Gill System, in part because of its enigmatic quality and because it doesn’t lend itself to “number chasing”; however, without a comparative scale, it doesn’t really help climbers gauge their level of climbing ability or improvement over time, which is one of the most important functions of a rating system (besides ego validation or inflation, close runners up). However, Gill considered artistic style to be as important as difficulty, and designed his rating system to avoid the type of numbers race that an open-ended system like the Sherman Scale tends to produce.

Gill’s system was designed, in part, to “discourage the degeneration of bouldering itself into a numbers-chase,” he said. “Unfortunately,” he acknowledged, “my system was a bit too abstract and went against the grain of normal competitive structures, where a simple open progression of numbers or letters signifies progress.” But Sherman, whose V-Scale provides a simple open progression of numbers to signify progress, soon lamented that his system had devolved into fuel for a numbers race; the hardest problem in his original Hueco Tanks bouldering guide was V9. “Instantly the race was on to be the first to climb V10,” he wrote. Then V11, and so on.

I tend to agree with Gill and Sherman: climbing isn’t all about numbers and should not be driven by sheer difficulty or a race to achieve the highest number for the sake of ego gratification, bragging rights, or to earn sponsorship dollars, but to approach problems in the spirit of exploration, discovery, and perfection of meditative and aesthetic, athletic movement.

Bouldering is an art form, not a competition.

Rather than trying to tick off some V8 problem and then start looking for a V9 to send, one should simply ask, “Can I get up that?” without concern about how hard it is, then work the problem until they can do it perfectly.

It turns out Gill and Sherman both claim to dislike subjective rating systems, at least for boulder problems. Gill wondered about the true nature of climbing difficulty, asking “Can there really be a uniform code describing it? Does it exist in some abstract, objective way?” He recognized that boulderers would ideally use a rating system to measure their improvement over time, but considered any system that sought to objectively define difficulty to be inconsistent at best, overly competitive at worst.

As for Sherman, when he turned in the first draft of his bouldering guide, it did not include ratings; his publisher insisted that a rating system be included, fearing a guidebook without ratings was doomed to failure, so he unleashed his V-Scale on us and, in doing so, as he wrote in his article, “To V or Not to V,” brought “the joy of number chasing to bouldering.”

Some old-school climbers still prefer the Gill System, in part because of its enigmatic quality and because it doesn’t lend itself to “number chasing”; however, without a comparative scale, it doesn’t really help climbers gauge their level of climbing ability or improvement over time, which is one of the most important functions of a rating system (besides ego validation or inflation, close runners up). However, Gill considered artistic style to be as important as difficulty, and designed his rating system to avoid the type of numbers race that an open-ended system like the Sherman Scale tends to produce.

Gill’s system was designed, in part, to “discourage the degeneration of bouldering itself into a numbers-chase,” he said. “Unfortunately,” he acknowledged, “my system was a bit too abstract and went against the grain of normal competitive structures, where a simple open progression of numbers or letters signifies progress.” But Sherman, whose V-Scale provides a simple open progression of numbers to signify progress, soon lamented that his system had devolved into fuel for a numbers race; the hardest problem in his original Hueco Tanks bouldering guide was V9. “Instantly the race was on to be the first to climb V10,” he wrote. Then V11, and so on.

I tend to agree with Gill and Sherman: climbing isn’t all about numbers and should not be driven by sheer difficulty or a race to achieve the highest number for the sake of ego gratification, bragging rights, or to earn sponsorship dollars, but to approach problems in the spirit of exploration, discovery, and perfection of meditative and aesthetic, athletic movement.

Bouldering is an art form, not a competition.

Rather than trying to tick off some V8 problem and then start looking for a V9 to send, one should simply ask, “Can I get up that?” without concern about how hard it is, then work the problem until they can do it perfectly.

The spirit of bouldering is, or at least should be, “Can I get up this section of rock?” rather than “How hard is this problem on some made-up, subjective scale?” or “I just sent a V10; where’s a V11?” The difficulty of a given boulder problem has never been of paramount importance in my decision to want to climb it. I enjoy the challenge of working out an interesting, aesthetic problem, however easy or hard it might be. If it turns out to be easy, I will eliminate holds until it is hard enough to be challenging. If it is too hard then, well, it is too hard.

So, is a rating really important? I don’t think so. But most people do. As Fred Beckey opined in his Cascade Alpine Guide, “A need for a rating system has long been recognized by American climbers...for simple words such as ‘easy,’ ‘moderate,’ and ‘difficult’ are subject to a variety of interpretations."

I disagree, which is why I use the Graham Scale.

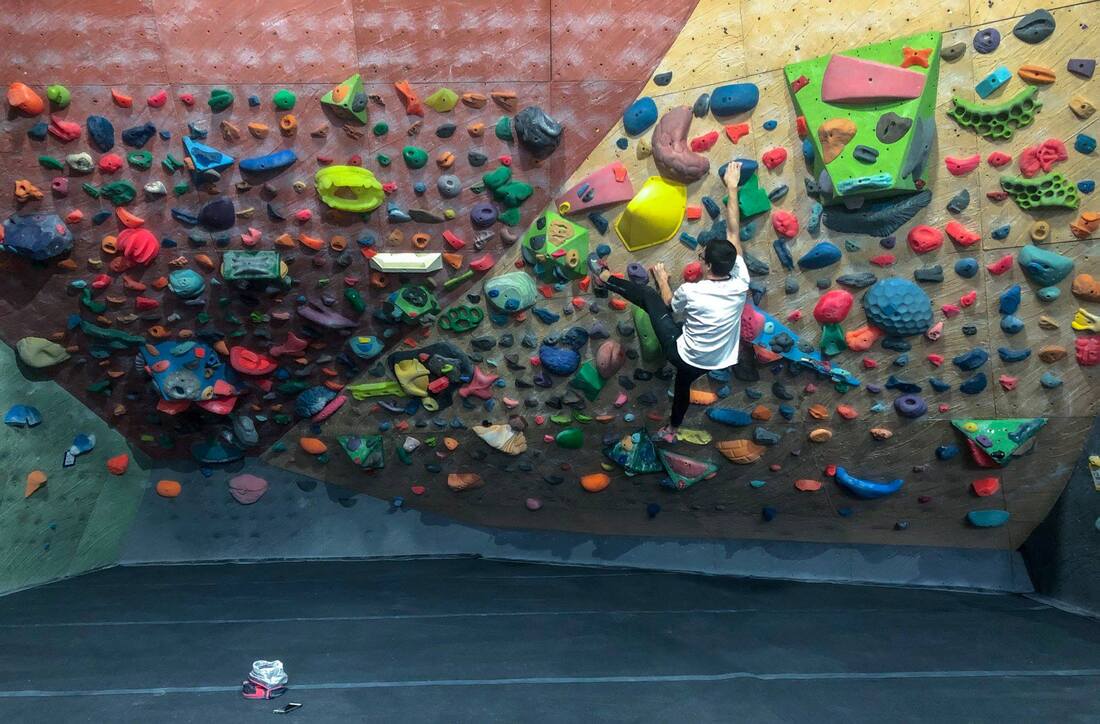

Rick Graham used to be a fixture at the University of Washington practice rock. A dead ringer for Captain Granitic, the lead character in a comic published in Climbing magazine in the 1980s, Graham would drive up in his work truck every evening, not bother to change out of his paint-splattered pants, lace up his EBs, and cruise up difficult problems like they were nothing. If you asked him how hard a given problem was, even if it was clearly much harder, he’d tell you it was 5.9 because, as he said, “5.9 is the ultimate difficulty possible. Fred Beckey said so.” Still, he might concede that a problem off the Beckey scale might be “hard,” “harder,” or “too hard.”

Despite what Beckey thought about a rating system that used simple words like “easy,” “moderate,” and “difficult” being too vague, subject to a variety of interpretations, and thus unpalatable to American climbers, I think this hard-harder-too hard system has merit. It certainly is not elitist; it is all about you.

So, is a rating really important? I don’t think so. But most people do. As Fred Beckey opined in his Cascade Alpine Guide, “A need for a rating system has long been recognized by American climbers...for simple words such as ‘easy,’ ‘moderate,’ and ‘difficult’ are subject to a variety of interpretations."

I disagree, which is why I use the Graham Scale.

Rick Graham used to be a fixture at the University of Washington practice rock. A dead ringer for Captain Granitic, the lead character in a comic published in Climbing magazine in the 1980s, Graham would drive up in his work truck every evening, not bother to change out of his paint-splattered pants, lace up his EBs, and cruise up difficult problems like they were nothing. If you asked him how hard a given problem was, even if it was clearly much harder, he’d tell you it was 5.9 because, as he said, “5.9 is the ultimate difficulty possible. Fred Beckey said so.” Still, he might concede that a problem off the Beckey scale might be “hard,” “harder,” or “too hard.”

Despite what Beckey thought about a rating system that used simple words like “easy,” “moderate,” and “difficult” being too vague, subject to a variety of interpretations, and thus unpalatable to American climbers, I think this hard-harder-too hard system has merit. It certainly is not elitist; it is all about you.

Under the Graham Scale, any problem up to 5.9 is rated using the YDS. Beyond that, it’s either hard, harder, or too hard. If a problem is hard for you, you call it “hard”; if it's really hard, you call it “harder”; if you can’t do it, it’s “too hard.” It’s entirely up to you and how you feel about the problem and your ability to solve it. It also allows you to track your improvement over time; as your skills improve, problems you thought were “hard” become, dare we say, “easy” (or, at risk of being a heretic, “moderate” or “difficult”); and problems that used to be “too hard” eventually transform into problems that are merely “hard.”

Some climbing gyms now have what they call a “spray wall,” a wall or series of walls with dozens of randomly placed holds, that allow you to make up your own problems, training circuits, whatever you want to do. There are no rated problems; nobody has set the problems and rated them for you; you make them up based on your preference, training desires, or ability. Unlike the other bouldering walls in the gym, problems on the spray wall are not defined or rated. Where does the problem go? Wherever you want. How hard is it? It’s entirely up to you.

Some climbing gyms now have what they call a “spray wall,” a wall or series of walls with dozens of randomly placed holds, that allow you to make up your own problems, training circuits, whatever you want to do. There are no rated problems; nobody has set the problems and rated them for you; you make them up based on your preference, training desires, or ability. Unlike the other bouldering walls in the gym, problems on the spray wall are not defined or rated. Where does the problem go? Wherever you want. How hard is it? It’s entirely up to you.

I know some people won’t be able to resist applying a numerical rating even to problems they make up on a spray wall. “Dude, it’s V8 for sure,” one will say. “No way, brah,” another will insist, “it’s V7.” There’s even a website called getstokt.com where you can upload your training wall and share and rate your problems. Frankly, this is silly. Whether a problem you make up on an artificial climbing wall is V7 or V8 makes no difference; it is what it is. Either you can do it or you can’t. Either it’s easy, hard, or too hard. Period.

A lot of gyms have gone to the circuit system of rating problems. Rather than giving a problem an exact rating, they lump problems of similar difficulty together by using color coding where, for example, problems with yellow holds are in the VB range, those with purple holds are in the V2-V4 range, those with blue holds are V5-V7, and so on. It’s almost as if they’re using the Graham Scale without knowing it, rating problems “easy,” “moderate,” “difficult,” “hard,” “harder,” and “too hard,” eliminating the numbers race without sacrificing the original spirit of a rating system—to let you know if a problem is suitable for your level of ability and give you goals to aspire to achieve rather than fueling a numbers race.

Even in bouldering competitions, the problems aren't rated; they just are what they are and are either easy, hard, or too hard for the competitors. Nobody gets difficulty points like in gymnastics; it's all about whether you can do the problem or not. Sure, the competitors talk about how hard the problems were—after the fact. But when they turn to face the wall when the clock is running, they have no idea. They’re just facing a problem and have to solve it. They know it's hard, maybe harder, but hope it's not too hard, at least not for them.

Alas, I know the Graham Scale isn’t going to catch on. We’re number chasers now, slaves to the ratings, who define our self-worth by a number we attach to rank our accomplishments. But who knows? John Sherman didn’t think his V-Scale would catch on, and look what happened.

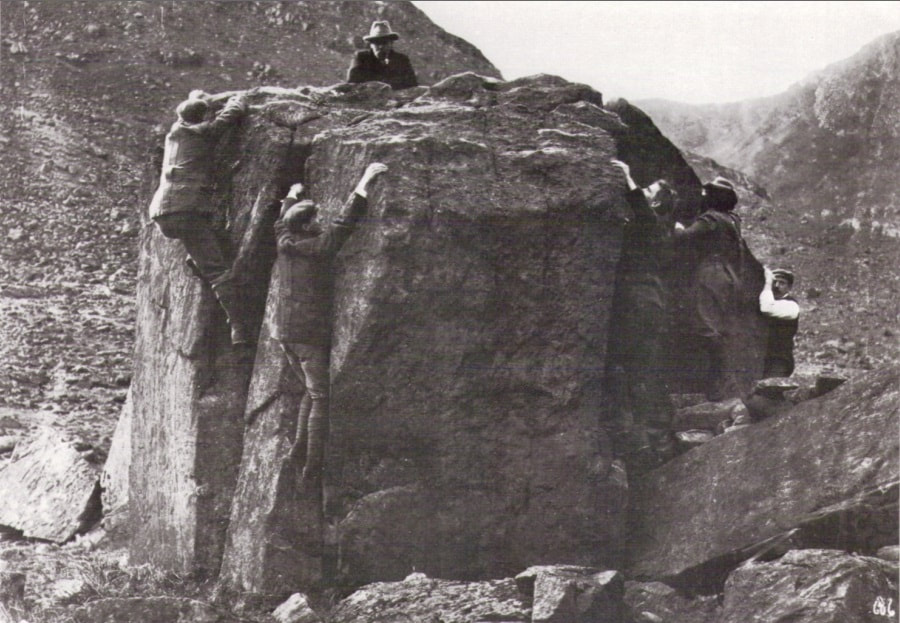

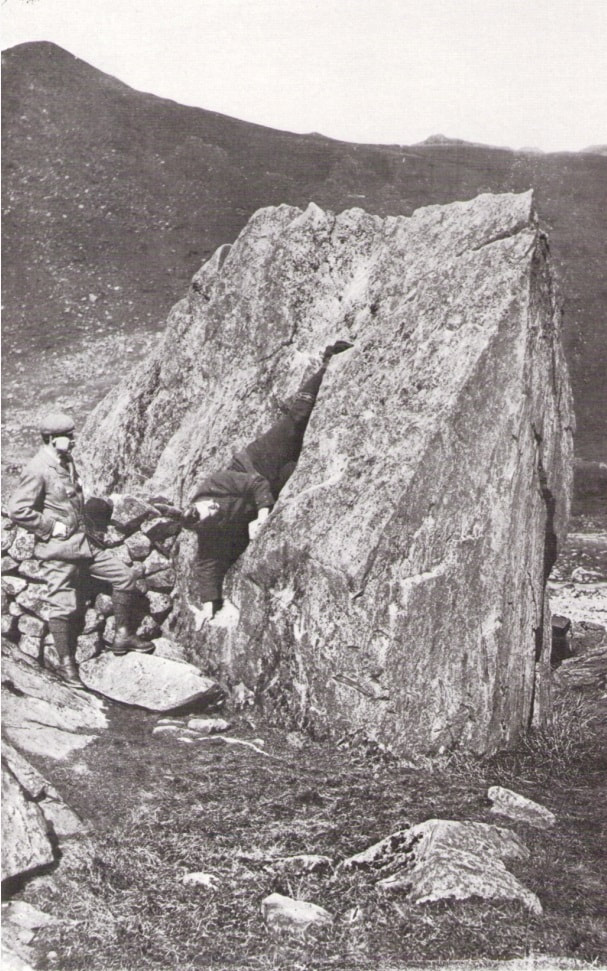

If you don’t like the Graham Scale, perhaps the Young Scale would be more to your taste? Consider this snippet from Geoffrey Winthrop Young’s 1905 buildering guide, Wall and Roof Climbing:

A lot of gyms have gone to the circuit system of rating problems. Rather than giving a problem an exact rating, they lump problems of similar difficulty together by using color coding where, for example, problems with yellow holds are in the VB range, those with purple holds are in the V2-V4 range, those with blue holds are V5-V7, and so on. It’s almost as if they’re using the Graham Scale without knowing it, rating problems “easy,” “moderate,” “difficult,” “hard,” “harder,” and “too hard,” eliminating the numbers race without sacrificing the original spirit of a rating system—to let you know if a problem is suitable for your level of ability and give you goals to aspire to achieve rather than fueling a numbers race.

Even in bouldering competitions, the problems aren't rated; they just are what they are and are either easy, hard, or too hard for the competitors. Nobody gets difficulty points like in gymnastics; it's all about whether you can do the problem or not. Sure, the competitors talk about how hard the problems were—after the fact. But when they turn to face the wall when the clock is running, they have no idea. They’re just facing a problem and have to solve it. They know it's hard, maybe harder, but hope it's not too hard, at least not for them.

Alas, I know the Graham Scale isn’t going to catch on. We’re number chasers now, slaves to the ratings, who define our self-worth by a number we attach to rank our accomplishments. But who knows? John Sherman didn’t think his V-Scale would catch on, and look what happened.

If you don’t like the Graham Scale, perhaps the Young Scale would be more to your taste? Consider this snippet from Geoffrey Winthrop Young’s 1905 buildering guide, Wall and Roof Climbing:

A list of graded international Problems, which it had been intended to include under the headings of Problematical, Highly Problematical and Absolutely Hypothetical, threatened to assume such vast dimensions and yet remain incomplete, that it has been thought better to leave the classification to local effort and a serial publication."

Indeed.

Hover over photos to see caption or click to enlarge and see caption.

Jeff introduced the Graham Scale in his 2018 books, Schurman Rock: A History & Guide, and Pumping Concrete: A Guide to Seattle-Area Climbing Walls. So far, the Graham Scale has not caught on, but you never know.