|

It seems like there’s always some weirdo at the climbing gym who, despite the efforts of some poor route setter who’s labored for hours to set the holds just so to create not just a climbing problem but a work of art, insists on climbing the cracks. That weirdo is usually me.

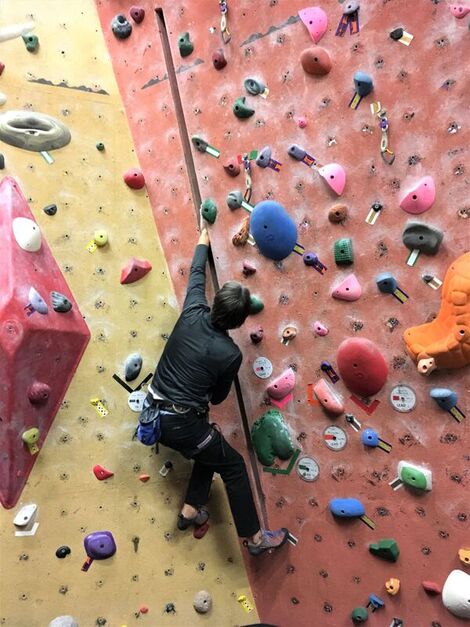

Not that I spend a lot of time in climbing gyms, mind you. Sure, I was there on opening night at Vertical Club in Seattle in 1987, but I never joined. I was pretty sure indoor climbing gyms were a fad, a dumb idea that would never catch on because climbers were cheapskates who wouldn’t pay money to climb indoors when they could climb for free outside. Maybe I didn’t like the original climbing gym because they didn’t have any good cracks, just some boards bolted together with some rocks and paint slapped on that were slippery and painful to climb. For the most part, nothing has changed. Most gyms have cracks—one or two straight in, parallel-sided slots set in the walls seemingly as an afterthought. They might be adequate for learning and practicing basic finger and hand-jam technique—sometimes even off-hand, fist, and off-width if you go to a fancy gym that has the luxury of extra wall space to devote to something ninety-nine percent of its members will never do—but they’re largely uninspired. There’s nothing artistic about them. They’re fine for learning the basics or pumping a few laps, but don’t get you fired up to spend hours or even days solving their complexities because, frankly, they don’t have any. |

Luckily, like any other climbing game, you can make gym cracks more interesting—dare I say fun?—by imposing rules. Once you’ve mastered the basics, you can climb them without using any of the bolted-on holds as footholds, relying on toe jams and foot jams or edging on the crack instead to make it more like real crack climbing. Then you can try to eliminate the crack for the feet as well, relying only on smears and nubbins on the wall’s scant features. If the crack is too short, you can add a sit-down start. And you can climb the crack with as few jams as possible, whittling it down to its bare minimum of jams and footholds. But you have to be a special kind of obsessed to put that kind of effort into climbing a fake crack on an artificial wall. I don’t know very many people who are that kind of obsessed. All I can say is, if you haven’t spent hours climbing the same fake crack fifty different ways, you are missing out.

|

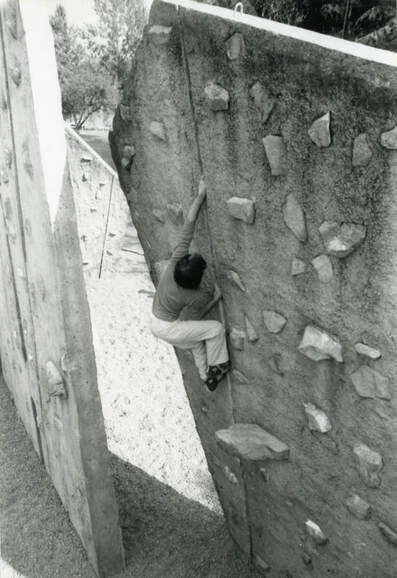

I started climbing before there were climbing gyms and most routes followed cracks. If you couldn’t climb cracks, you couldn’t climb, period. Luckily for me, the University of Washington (UW) built an artificial climbing wall in 1976 that was just an hour’s bike ride from my home. The wall was supposed to offer introductory-level training, with problems starting in the 5.4 range, but the wall’s architect miscalculated and inadvertently created a high-level artificial bouldering wall that had not only difficult face climbs, but even more-difficult cracks—finger cracks, hand cracks, fist cracks, shallow flares, angling, vertical, overhanging—nearly every type of crack (except off-width), all with rough concrete sides and edges that tore into your skin, resulting in a lot of bloodshed.

|

Despite the pain and trauma involved in learning to climb cracks at the Rock, you kept coming back until you toughened up your hands and honed your technique. Then the games began: eliminating foot jams, laybacking with features only for the feet, using only five jams, then four, then three, sometimes even just two jams to climb a twelve-foot crack (or as many jams as possible, cramming fifty or more distinct jams into fifteen feet of crack). This sort of neurotic fixation translated to a new level of crack-climbing proficiency, allowing me and my fellow rock rats to work our way up to doing 5.12 and 5.13 crack climbs. That was was exciting, sure, but there was nothing like the special thrill of climbing a fifteen-foot angling concrete finger crack with three jams from a sit-down start using features only for the feet. Like I said, it’s a special kind of obsession. You either have it or you don’t.

The UW Rock aside, modern fake cracks have not, as a rule, sparked anything resembling passion in me, although I occasionally find a gem, like the six-foot overhanging thin-hand crack I found on an artificial boulder in a suburb south of Seattle. It’s a classic Entre-Prises crack: sharp edged, shallow, flaring in all the wrong places, grating on the skin, but otherwise perfect. I milked it for all it was worth, climbing laps up and down, minimizing then maximizing number of jams per lap, using only fingerlocks or thumbs-up jams, laybacking the edge, you name it. One day I put in an El Cap day: ten sets of 25 laps, 250 laps total, 3000 feet of climbing, six feet up, six feet down, repeat ad nauseam.

|

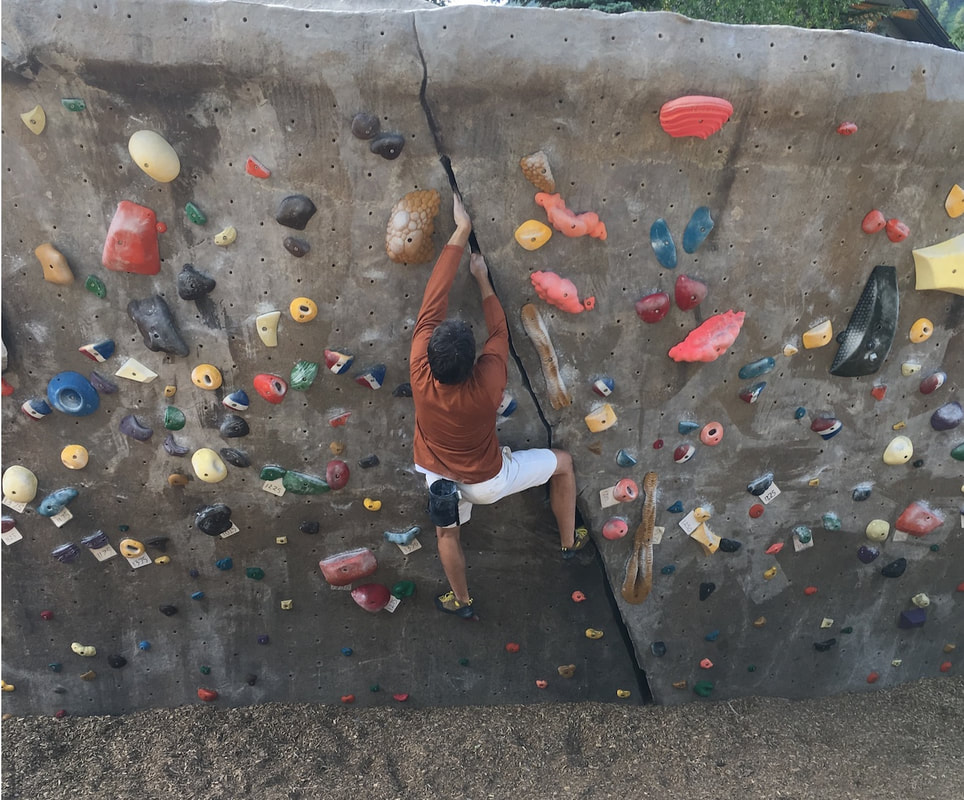

So it was that I fell in love with a certain overhanging thin crack at the Teton Boulder Park in Jackson, Wyoming. I had seen photos of the bouldering park online and, being an artificial climbing wall aficionado, decided to drive several hours out of my way to make a stop there on my way from Seattle to the International Climbers’ Festival in Lander to check it out. The bouldering park, located in Phil Baux Park at the base of Snow King Mountain on the south end of town, is the size of a small bouldering gym. It consists of three large artificial boulders of the fiberglass-and-textured-polymer-cement-shell variety with colorful plastic holds bolted all over the wall and--yes!—a few interesting-looking cracks. (Plus, it’s free to climb there.) Although I arrived early in the morning, there were already several people there, traversing across or climbing the vertical and overhanging faces, working the defined problems, pulling on the plastic holds and, of course, ignoring the cracks. |

I judge fake rocks by their cracks, which usually suck. I admit, however, that cracks on the cement-shell boulders, despite their suckiness, are often challenging. They are usually shallow, bottoming, irregular, rough-edged, and almost entirely unsuitable as training for actual crack climbing. You’d think I’d like that, and I do in a perverse sort of way, but in most cases these cracks are awkward and painful to climb. They lack purity, artistry, realism, and so as a rule I don’t like them. And I didn’t like most of the cracks at the Teton Boulder Park. How can I say it in a nice way? They sucked. Except that one crack. It was a beauty.

I saw it immediately: a shallow, flaring finger crack with a couple of thin-hand slots angling leftward up an overhanging twelve-foot wall on the front side of the biggest boulder in the park (originally called the Boxcar Boulder, it’s shaped more like a ship, hence its nickname: S.S. Badass). It was, if I may say so myself, perfect, irresistible even, a work of art. And so, I spent the better part of the morning obsessively focused on trying to climb it, much to the quiet amusement of the other climbers, I’m sure. One young man indulged my suggestion that crack climbing was fun and he should try it, but he had the good sense to quit after a couple of tries and return to pulling plastic.

The crack was easy enough from a standing position, using the many yellow and red bolt-on holds as footholds, but unsatisfying. It was too easy. To climb it properly required a sit start and elimination of all the footholds. But, after many tries, I couldn’t work out the middle section, a shallow, flaring offset that defied all my attempts. I tried several different sequences, but my fingers kept popping out or my feet kept slipping off the smooth cement-shell face, landing me unceremoniously in the crash pit. My fingers started to get sore; if I kept at it, I’d be bleeding soon. I taped up and tried some more, to no avail. Eventually, it was time to leave. I rested up for one last try. It was a good one. I nailed the sequence through the middle section and reached into a shallow hand jam, but my fingers ripped out of the flare and I fell, landing on my back on the wood chips with an audible thud.

|

I wanted to stay longer, but realized it would be silly to spend all day flailing on a twelve-foot crack on a fake rock. “What took you so long?” someone would ask when I arrived in Lander well after dark. “Well…” I would answer, my eyes cast down, unwilling to explain. No, I was not that obsessed. I headed out for Lander, sad, but determined. I swore an oath that I’d climb that accursed crack if I ever came back through Jackson, although I didn’t plan to come back through Jackson anytime soon. Still, I couldn’t stop thinking about it, running through the sequence in my mind, visualizing myself making the moves, reaching the top, totally stoked, pumping my fists furiously and letting out a barbaric yawp. I met some sport climbers at the festival and told them about the crack. “If you’re ever in Jackson,” I said with a look in my eyes that suggested I might have recently escaped from some sort of institution, “you have to try it.” “Whatever, dude,” they said, their eyes visibly glazing over. Still, while we were bouldering in Sinks Canyon a few days later I got them to try crack climbing and they liked it so much they spent an hour climbing one particular crack, eliminating jams, sit-down start, the works. Once guy figured out a way to climb it without any jams at all. On my way home from Lander, I’d planned to drive up Highway 191 to Bozeman, Montana, which seemed like the shortest route home. But when I was informed that I’d have to pay to drive through Teton and Yellowstone National Parks (“Pay to drive on a taxpayer-funded highway? Outrageous!”), I changed my mind. I turned around and headed south, which conveniently took me back through Jackson. |

|

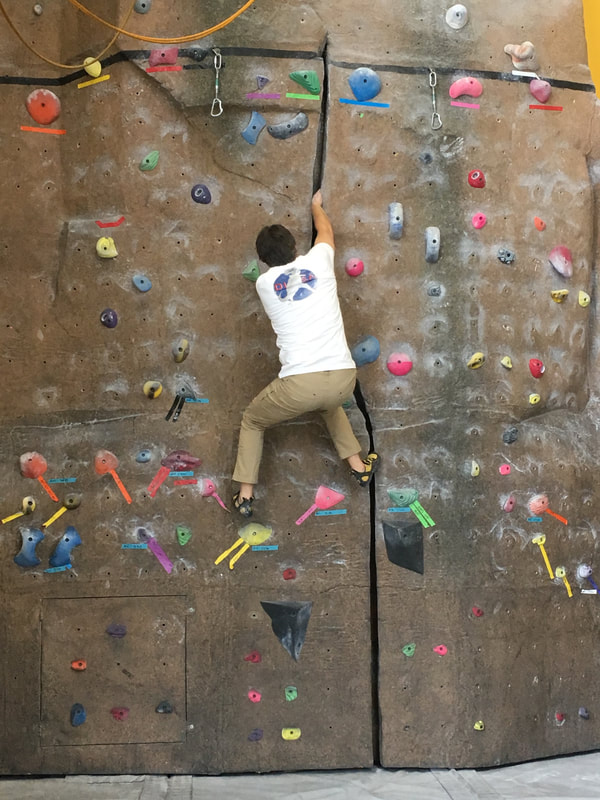

Forty-five minutes later I pulled into Phil Baux Park. It was midday, and the park was full of people doing normal things like picnicking, yoga, playing Frisbee, and pulling on plastic holds. As usual, I was the only weirdo there. I laced up my rock shoes, chalked up, approached the boulder, and sat down. People looked at me funny, but I didn’t care. I stuffed my hands into the flaring crack, pulled up, and reached for a flaring slot. I locked my fingers in the slot, wedged my right foot into the flare, smeared my left foot onto the flat wall, and repeated. I flowed through the moves easily. Near the top, I stuffed my hands into thin, sharp-edged jams, then locked my fingers in a final, jagged slot, brought my feet up onto tenuous holds, and fired for the top edge of the boulder. I caught the lip, grabbed it with both hands, hooked a heel over the ledge, and flopped my way to the top.

You might think that, after I’d fulfilled my dream of climbing that vicious little crack, I’d have no reason to return to Jackson, Wyoming. You’d be wrong. You see, there’s another crack at the Teton Boulder Park, steeper and thinner, rising in a rainbow arc splitting the very bow of the S.S. Badass. After I’d sent my project, I gave it a few tries. It seemed do-able. A little hard, maybe, thin fingertips with poor-to-nonexistent footholds, but something I might have been able to do it if I’d worked it for a while. If I’d had time, I might have tried to do it with three jams even, or maybe just two. But it was getting late. I needed to get back on the road. Maybe next time, if I ever get back to Jackson. |

Jeff Smoot is the author of numerous climbing-related books including this one that explores the history, culture, and legacy of the artificial climbing wall phenomenon: Pumping Concrete: A Guide to Seattle-Area Climbing Walls: Smoot, Jeff: 9780692103531: Amazon.com: Books