When climbing in The Blue Mountains of Australia (or The Mountains as known to the locals) it’s easy to recognise its climbing past. Carrot bolts (a special Aussie form of protection) are still clipped and legendary routes have white worn edges smoothed down from generations of “wanna, gonna’s” who soon move on to wildly steep lines.

Whilst tips and tendons recover, it’s nice to take time to draw on where we have come from and the climbers who preceded us.

I first met Andrew Penny as a teenager. A climbing mate, Ben Pearce, scored me and himself a job with Andrew’s Blue Mountains Climbing Company. In the mid 1980’s there were only two climbing guide businesses in The Mountains, Andrew’s and Glen Nash’s, Australian School of Mountaineering. To be paid to guide by either of them was like a teenager being given an X-Box for liking TV.

After guiding a set of European Ladies up the West Wall of the Three Sisters, Andrew met Ben and me at the Echo Point car park and paid us in cash - my first professional climbing job. I felt like Don Juan. I liked this climbing game.

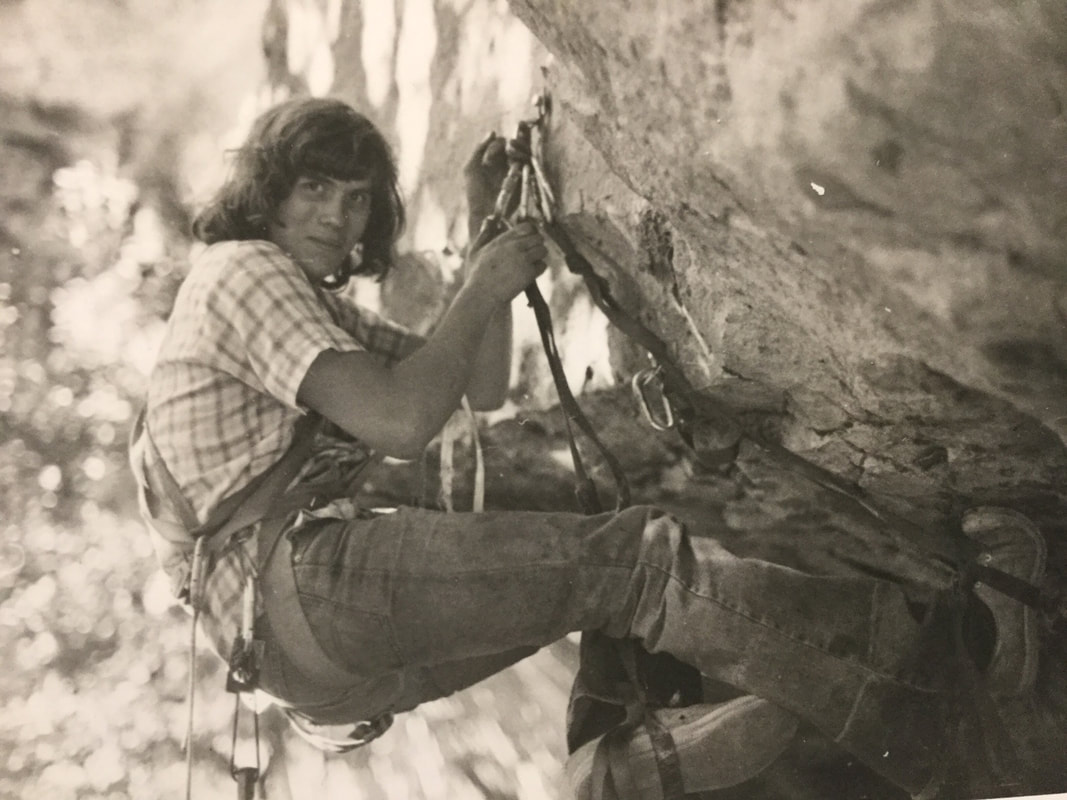

Andrew had identified climbing as his purpose early in his journey and used it to guide his life. His beginnings are similar to many climbers of that era.

Whilst tips and tendons recover, it’s nice to take time to draw on where we have come from and the climbers who preceded us.

I first met Andrew Penny as a teenager. A climbing mate, Ben Pearce, scored me and himself a job with Andrew’s Blue Mountains Climbing Company. In the mid 1980’s there were only two climbing guide businesses in The Mountains, Andrew’s and Glen Nash’s, Australian School of Mountaineering. To be paid to guide by either of them was like a teenager being given an X-Box for liking TV.

After guiding a set of European Ladies up the West Wall of the Three Sisters, Andrew met Ben and me at the Echo Point car park and paid us in cash - my first professional climbing job. I felt like Don Juan. I liked this climbing game.

Andrew had identified climbing as his purpose early in his journey and used it to guide his life. His beginnings are similar to many climbers of that era.

I ventured into climbing by accident knowing nothing about it. A teacher at my boarding school in Sydney took a small group of us up to The [Narrow] Neck and The Three Sisters. It was out there.”

Andrew became hooked on climbing during the feeding frenzy of the early 80’s and was a member of a young crew of climbers including Kim Carrigan, Mikl Law, Greg Child, and John Smoothly. These climbers (among others) cut their teeth on machined and mild-tempered carrot bolts complimented by choss and vegetated cracks put up by John Ewbank and company in the 60’s and 70’s. Andrew speaks highly of those times and of its climbers:

I have the utmost respect for John Smoothy who pioneered hundreds of quality routes in the Bluey’s. Crunch (as John was known) was as dry as they come and a fountain of knowledge in Mountains climbing. Mikl Law, Giles Bradbury, and Warwick Baird were a real inspiration with their vision and climbing style. They typified the individualistic nature of our game.”

Andrew often speaks of climbing as a game. When there weren’t enough climbers to write a new chapter of history, and whilst still too young to know how to write one, they crossed over to the sunny side of the Blue Mountains - a new age of explorers who wore flares, swapping leads, and drawing straws for new routes every time they met.

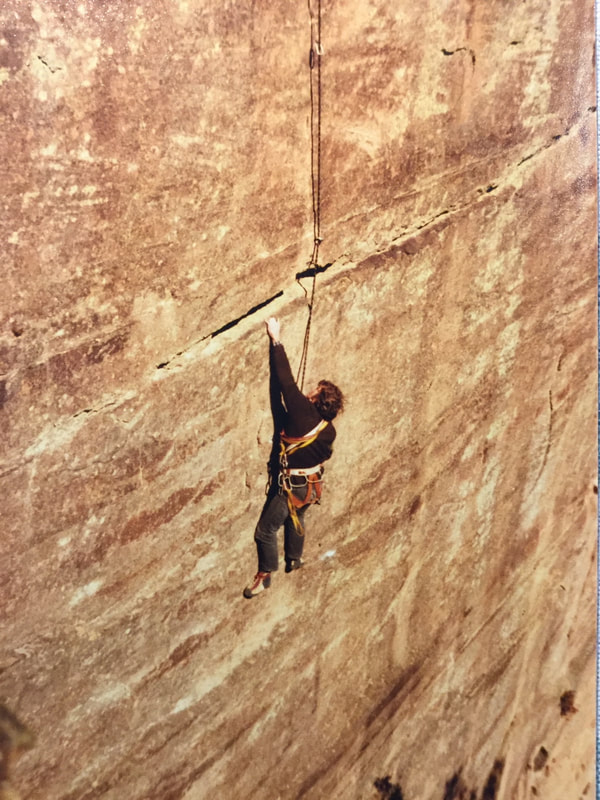

While some climbers and the occasional Queenslander found their straps jamming up and pulling down Blue Mountain’s test pieces, other’s left for challenges down south with the Victorians, or climbing high on big white stuff in postcard countries. Andrew set anchor in The Bluey’s and started drilling down on its potential. The draw of The Mountains is clear when he reflects on what climbing was to him:

Climbing was my life and my only interest for twenty years or so. Climbing took precedence over work or any career. I loved the freedom, the challenge, and the mateship.”

That sounds familiar, I am sure, to climbers today.

Andrew’s affair with climbing is no more obvious than checking out any Blue Mountains guidebook. He had his hand in exposing new crags and climbs up and down the escarpment. As a young climber he and his accomplices developed their craft for new routing at Narrow Neck following old lines and forging new ones on the faces and arêtes in between them. As this new-wave generation of climbers gathered momentum, so did their flare for finding new crags. A crowning achievement for Andrew was the development of Cosmic County, more commonly known today as, The County. Andrew speaks fondly of this time:

Terry Bernutt and John Smoothy kicked it off with Interstate 31 (17/5.9). Legend has it that Terry saw this stellar line while working on the railroad.”

The County became Andrews’s new obsession and was the first crag he helped develop from scratch. The vertical walls and arêtes were, at times, desperate, often sustained, and above all fun. This was where climbing was headed and it suited Andrew’s style.

I loved the whole scene out there in the early 80’s. Cutting a road in, clearing a campsite, building tracks, and the odd steel ladder or two.”

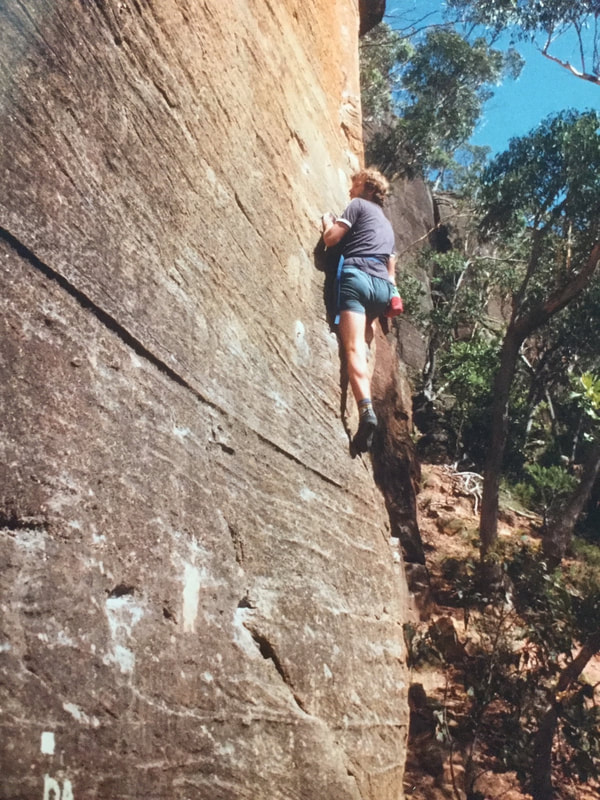

Some thought that this type of development just wasn’t cricket, and bolting walls was commonly seen as excessive. The County in the 80’s was like Nowra in the 90’s, a place to push boundaries, to bolt for purpose not for emergency, and to take climbing into new territory. Andrew completed some notable climbs of the time:

I always liked the balance-y routes especially the aretes. My two favourites of that time are The Eighty Minute Hour (18/5.10a) and I’d Rather be Sailing (19/5.10b). Oh yeah, and add the Allied Chemical News (17/5.9).”

If you have been climbing long enough, these climbs were on THE tick list of a new generation of Blue Mountains climbers. What’s more the style of the climb, direct, one or two pitches and well bolted was heralding the future. This was a new set of standards that was soon to be confronted by climbing ethicists and old school believers, the rest of us knew these times as, The Bolt Wars.

Andrew was a prominent protagonist of this revolution and there was heated debate for a decade in and around this topic. Friends fell out and bolts were chopped as puritanical clean climbers tried to defend choss and run outs as the law.

The Mountains became the Wild West and young cowboys harnessing drills and flashing cold steel carrot bolts and homemade hangers were heralding a new direction. Andrew’s singular focus might have deafened him from the noise, but he recognises it was a jarring moment in the development of climbing in Australia. In subsequent years he has had time to think this through.

The Bolt Wars were a big deal for us all back then. Lot’s of folks gave you grief for equipping routes and setting anchors. In hindsight, bolting has proven just. If anything bolts and safely arranged anchors are the standard now.”

Turning pages of the climbing mags of the era, Rock and Australian Rockclimber, the conflict was well reported, sides chosen, climbing styles argued over (I reckon there was a bit of shit-stirring as well). Andrew acknowledges that he may have exercised some overreach in these changing times.

I think some people misunderstood my motives. It wasn’t about ego. I just enjoyed bolting and climbing new routes. Creating popular, well-protected climbs in the easy/medium grades was very satisfying. My obsession with bolting started at age 15 when my teacher warned me about the evils of bolts. I placed my first one soon after.”

|

If anything, Andrew was an early spark in what was to become the flame in Blue Mountains climbing. Today, prepared routes, good access, and a high standard of bolting are the norm. In the contemporary Blue Mountain scene, climbers are able to concentrate on the ascetics of movement and the edge of human endeavour, not a pants-filling expectation of death, negotiating the loose and run out horror shows that defined the past. Andrew has also informed and developed the way climbing is communicated. He was the “Town Herald” of Blue Mountaineering. As Andrew continued to build a solid base in The Mountains, so did his knowledge of what had been and what was being developed. Back-in-the-day there was no internet and not a lot of mediums to get information to the climbing community. Andrew Penny saw a need and addressed a shortage of climbing information. Self-published guides were time consuming and expensive (still true, I’m sure Simon Carter will agree.). But, Andrew pressed on, researching, collating, and publishing new route data and area guide books. These books had photo’s of climbing heroes schmoozing on sunlit sandstone and stories within the route descriptions. I remember my photo-copied Narrow Neck Guide, and falling asleep reading Andrew’s Wolgan Guide, which was as thick as a Bible. |

I gathered what info I could from any available source. John Ewbank’s 1967 Blue Mountains Guide and Pete Taylor’s 1974 Wolgan Guide were the bedrock for my own guidebooks. Way before Google and social media, the Sydney Rock Climbing Club had a Climbs Recorder. That was your way to get the current news.”

Every subsequent guidebook expands on those that precede it. Writing guidebooks is like standing on the shoulders of giants. Andrew Penny is a Blue Mountains giant. A sign of his thoughtfulness came out when I asked him about the latest Blue Mountains Guide. Andrew says:

Simon Carter’s guide is really amazing. Brilliant photos, maps and insight covering so much climbing in such a readable and enticing way.”

Having been a working part of The Mountains climbing community for fifty years, I asked him what he thought of the scene today?

It’s great to see such an incredible range of climbs and crags available. The combined efforts and different visions of so many. Sure it can be super competitive to some, and what they are achieving is awesome. However, I really like the social aspect of it all. People just going out with their friends and having fun. Gym, sports and trad climbers, it doesn’t matter, they are out there doing it.”

Andrew is still doing it and gets out on the rock when he can. He has plenty to recollect on a rainy day if stuck at home. He smiles when thinking of evenings long past, climbing the roof in Waterfall Cave at Narrow Neck whilst mates choked by the smoke of a campfire or of introducing people to climbing as a climbing guide and of seeking out new routes in odd corners of The Wolgan Valley.

Catching up with Andrew Penny was a trip and a trip worth taking – Cosmic even. The future of Blue Mountains climbing is further enhanced by having knowledge from the climbers who pulled down and faced the future in a previous era. Andrew Penny is one of those guys - a Blue Mountaineer.

Catching up with Andrew Penny was a trip and a trip worth taking – Cosmic even. The future of Blue Mountains climbing is further enhanced by having knowledge from the climbers who pulled down and faced the future in a previous era. Andrew Penny is one of those guys - a Blue Mountaineer.

Andrew Penny Guidebooks

1. The Rock Climbs of Narrow Neck (1978)

2. The Narrow Neck Supplement (1979)

3. A Climber’s Guide to the Northern Hartley Valley (1981 - Covering Cosmic County and Dargan's Creek)

5. A Climber’s Guide to Mt Piddington by Andrew Penney and Mike Law (1982)

6. A Climber’s Guide to the Rest Around Mount Victoria (1982)

7. The Wolgan Guide (1984)

8. The Cosmic County Guide (1988)

1. The Rock Climbs of Narrow Neck (1978)

2. The Narrow Neck Supplement (1979)

3. A Climber’s Guide to the Northern Hartley Valley (1981 - Covering Cosmic County and Dargan's Creek)

5. A Climber’s Guide to Mt Piddington by Andrew Penney and Mike Law (1982)

6. A Climber’s Guide to the Rest Around Mount Victoria (1982)

7. The Wolgan Guide (1984)

8. The Cosmic County Guide (1988)