For those who enjoy listening to a story, the author Bavali "Megs" Hill has recorded herself reading The Three Sisters.

One hundred and twenty kilometres west of Sydney lies a blue-hazed mountain range, ancient and mystical.

The Blue Mountains, where millions of gum trees soak up the sun’s heat and release fragrant eucalyptus oil into the air, attained their name from the suspended oil that absorbs and refracts the light, tinging the lines of the ochre and black cliffs to blue and dissecting the valleys with shadows of navy and purple. The Blue Mountains National Park is just a slice out of the bony wrinkle of mountains that run down the length of Australia’s east coast, thus forming the Great Dividing Range; the Blue Mountains being an early and imposing barrier to the westward expansion of Sydney.

Only a ninety-minute drive from Sydney to Katoomba - but with a mind boggling 300 million years of history - are the repeated sedimentary layers, cataclysmic uplifts, and climatic changes that lie between the city and this prehistoric sandstone plateau. The weight of time with wind and water has worn the rocks over millennia, crumbling and eroding it into the ridges and cliffs that climbers love so much.

The Blue Mountains, where millions of gum trees soak up the sun’s heat and release fragrant eucalyptus oil into the air, attained their name from the suspended oil that absorbs and refracts the light, tinging the lines of the ochre and black cliffs to blue and dissecting the valleys with shadows of navy and purple. The Blue Mountains National Park is just a slice out of the bony wrinkle of mountains that run down the length of Australia’s east coast, thus forming the Great Dividing Range; the Blue Mountains being an early and imposing barrier to the westward expansion of Sydney.

Only a ninety-minute drive from Sydney to Katoomba - but with a mind boggling 300 million years of history - are the repeated sedimentary layers, cataclysmic uplifts, and climatic changes that lie between the city and this prehistoric sandstone plateau. The weight of time with wind and water has worn the rocks over millennia, crumbling and eroding it into the ridges and cliffs that climbers love so much.

|

It's 1969. Our driver says, “We’re almost there now”, tapping on the map at Katoomba’s Echo Point - the best vantage spot for viewing our climbing goal, the West Wall of the Three Sisters.

Looking south, the Kedumba River is a mere indentation in the tree line at the valley bottom. Mount Solitary, sitting squat and stolid, is dead-centre behind. A jutting promontory to our left is the home of the three monolithic fingers of The Sisters, like a desperate hand reaching out above the ancient oceans which used to cover these lands. Young and energetic, we move at speed in our Volley sandshoes, with ropes and climbing gear jangling. We bounce down 900-near-vertical steel and stone steps cut into the Sisters’ east face. It’s a jarring, jolting descent, our insides shaken and knees quivering by the time we reach the bottom. |

Following the track, we reach the base of the impressive Sisters’ West Wall, iconic and encouragingly familiar, as it graces souvenir tea towels, bookmarks, and teaspoons; it has been instilled into our consciousness since childhood. With some uncertainty on the exact start, we "bush bash" up the scree slope of thick vegetation to the point where it meets the cliff face – a WW chipped into the rock indicates the beginning of the climb. From this angle the cliff is intimidating.

The yellow, honeycomb erosions and pock-marked black rockface rises over 200 metres (650 feet) above the scree to the top of the three pinnacles. The Sisters’ West Wall climb was originally graded 10 (5.3) in John Ewbank’s 1967 Guide but is now given a 12 (5.5) in the more recent guide by Simon Carter. While I wait for the leader to sort the gear, there is time to absorb the glinting treetops and bask in the immense silence.

I know a little of the Aboriginal origin of these three pillars. Three sisters from one tribe fell in love with three brothers from a neighbouring tribe, but their love was forbidden by the Elders. A tribal war ensued. For protection, the sisters were turned into pinnacles of rock by the medicine man, who, unluckily for everyone, died in battle before reversing the spell. Since then, the sisters remain for all time imprisoned in the rock, towering sentinels over the Jamieson Valley spread out below.

The yellow, honeycomb erosions and pock-marked black rockface rises over 200 metres (650 feet) above the scree to the top of the three pinnacles. The Sisters’ West Wall climb was originally graded 10 (5.3) in John Ewbank’s 1967 Guide but is now given a 12 (5.5) in the more recent guide by Simon Carter. While I wait for the leader to sort the gear, there is time to absorb the glinting treetops and bask in the immense silence.

I know a little of the Aboriginal origin of these three pillars. Three sisters from one tribe fell in love with three brothers from a neighbouring tribe, but their love was forbidden by the Elders. A tribal war ensued. For protection, the sisters were turned into pinnacles of rock by the medicine man, who, unluckily for everyone, died in battle before reversing the spell. Since then, the sisters remain for all time imprisoned in the rock, towering sentinels over the Jamieson Valley spread out below.

Nowadays, we are learning to acknowledge Aboriginal peoples and respect their continuing habitation from ancient times, their reverence for this searingly beautiful land, the fabric of their stories and dreaming. But back in the 60s and 70s when I was climbing The Sisters, this was before our knowing.

Climbers felt that by scaling a crack or a wall all the way to the cliff’s top, by knowing rock intimately - running our fingers over its contours; breathing in the fragrance of warmed sandstone and sweat, and melding with pungent, cool dampness in rock crevices - that we belonged to this rock and wilderness. Back then, we felt our passion and respect for rock, our skill, and the camaraderie of climbers gave us independence - and ownership.

On this day, at the age of 19, as I stand below The Middle Sister, I feel terror and excitement in anticipation of my first long climb. I'm not sure if it means anything to the rock, or the women that lie within it, that I, too am the middle of three sisters. It also crosses my mind that I am a young woman who can choose whom I love. I can also move to Sydney to consciously live without interference from my elders. Strangely and intuitively, I feel for the Three Sisters being eternally entombed in rock.

Climbers felt that by scaling a crack or a wall all the way to the cliff’s top, by knowing rock intimately - running our fingers over its contours; breathing in the fragrance of warmed sandstone and sweat, and melding with pungent, cool dampness in rock crevices - that we belonged to this rock and wilderness. Back then, we felt our passion and respect for rock, our skill, and the camaraderie of climbers gave us independence - and ownership.

On this day, at the age of 19, as I stand below The Middle Sister, I feel terror and excitement in anticipation of my first long climb. I'm not sure if it means anything to the rock, or the women that lie within it, that I, too am the middle of three sisters. It also crosses my mind that I am a young woman who can choose whom I love. I can also move to Sydney to consciously live without interference from my elders. Strangely and intuitively, I feel for the Three Sisters being eternally entombed in rock.

|

“Look!” I point upwards.

Two wedge-tailed eagles (wedgies) have the sky to themselves, soaring in effortless circles on the warmth of rising thermals. After a wait, I see the rope moving upwards, then tighten against the big-D carabiner snapped into the seatbelt webbing secured around my waist (which we used before the original Whillans harness arrived.) I hear my partner yell, "On belay" and I tentatively begin the first of the nine pitches. It’s about finding the right notch to hold onto, moving up slowly, pressing hard against the rockface, reaching, pushing down, making small gains, feeling and sensing the rock with the reassurance of the top-rope above me. My skin smells sweetly of sandstone and my fingertips are getting tender. Gradually I trust my balance and the rock’s solidity – until it unexpectedly breaks off or crumbles; or when the leader yells a warning, “Beloooooow!”, and I flatten against the wall or duck low to avoid falling rocks and a shower of dirt. We hope luck is on our side. |

The first five pitches are a series of walls and corners, between 20-40 metres (65-130 feet) each, until the scrubby horizontal half-way ledge - pitch six - is reached. It is described as a "scramble" but we rope up anyway to give greater safety. We pick our way diagonally over dislodged rocks, shallow rooted bushes and dirt that comes loose in handfuls. Although described as a ‘ledge’, it is in fact a steep slope of scrubby vegetation and too easy for us to send big rocks falling to the depth below. How effortless it would be to slip here. I’m reminded of the fragility of life, both for us as climbers and for the plants and insects we encounter. The Sisters’ lives were cut short in an instant, without warning while they yearned for their young men. It is a pity that this shrubby belt at the sisters’ waist is such a brittle and fragile one and a portent to its future banning. But soon, I bring my focus back to the rock as we reach the next pitch, at the base of the clear crack between the Second and Third Sisters.

By the eighth pitch my arms are aching and tired. Fear and excitement on difficult moves below sapped my stamina early, thrutching out for a "thank-god" handhold where, with much later experience, I would be able to find an easier, smoother move.

By mid-afternoon, the black rock heats up and breezes dry my sweaty t-shirt. I wipe wisps of hair from my mouth. Here the corner crack is vertical and too smooth for plants’ roots to take hold. One wall is sheared into a concave, powdery orange that I don’t want to trust. On the left, the rock is black and hard with only match-head-sized ironstone protrusions and indentations for traction. I hope there are finger holds in the corner, but I watch carefully how Warwick, who is leading, tackles it – that’s the advantage of being second in line, you can watch and learn. But his extra height, arm strength, and experience provide more options than those available to me.

This is the crux pitch of 21 metres (70 feet). It’s clear there is no other way than straight up. My breathing is heavy, and chest is tight as I begin. Each finger hold seems desperate, and I can’t believe that the rubber edge of my Volleys (tennis shoes) can stick on such small, jutting out pebbles. I’m panting, as much from panic as from exertion. My eyes desperately search for another hold, so I can move up. Each move is into uncertainty, but I have to keep up the momentum. I can’t freeze on this wall – there is no possibility of retreat.

On the top of pitch 8, exhausted and emotionally depleted, I heave myself onto the ledge, assisted by the reprieve provided by a tight top rope. It feels like I am exhaling for the first time. Warwick sets up for the next, final pitch.

As he disappears from view, I’m alone on a thin, sandy ledge, watching skinks leave footprints, simply listening and alert to feeding rope as I belay. I watch as Narrowneck, the long cliff-lined plateau on the far side of the valley, casts a shadow across the valley floor as the sun starts to drop towards it. A lyre bird’s chatter reaches me as it scratches in a shaded gully far below. There is just thin air and a sizeable and sobering drop beneath me.

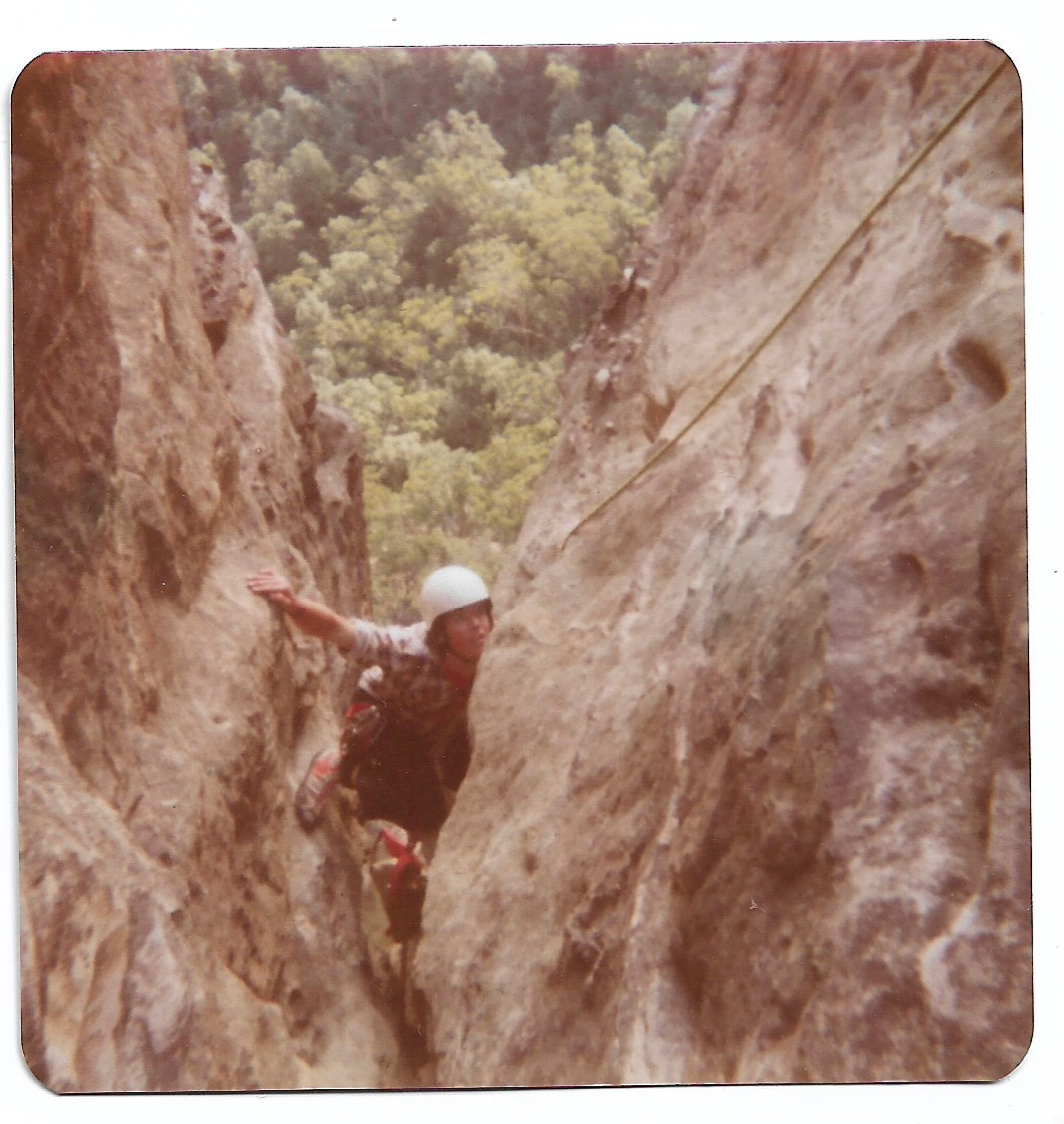

The last pitch is tricky. Once clear of the exposed face, the only way up is through twenty-one metres (70 feet) of chimney - two walls with a narrow gap between, pushing with my back against one wall and my knees, feet and hands pushing against the other, inching upwards, looking for any advantage, a jut, crack, or hold to gain purchase. Every move is an effort. Looking down, I know that only opposing pressure against the two walls keeps me from falling and being jerked to a halt by the top-rope. I also know that getting back into the chimney position from here would be a challenging manoeuvre after a fall. The mantra of "don't fall" plays repeat in my head. The rocks bite into my hands, as I clench on harder in reflex.

The rear of the chimney continues to narrow. It now feels as though I will be trapped in this slot like the Aboriginal sisters of legend. The walls close in, and the smell of lichen and cold air amplifies the feeling of constriction. To escape my imprisonment, I am forced to move out closer to the very edge, which at this point overhangs the valley without interruption. It is terrifying and my legs are trembling. I understand exposure for the first time.

By mid-afternoon, the black rock heats up and breezes dry my sweaty t-shirt. I wipe wisps of hair from my mouth. Here the corner crack is vertical and too smooth for plants’ roots to take hold. One wall is sheared into a concave, powdery orange that I don’t want to trust. On the left, the rock is black and hard with only match-head-sized ironstone protrusions and indentations for traction. I hope there are finger holds in the corner, but I watch carefully how Warwick, who is leading, tackles it – that’s the advantage of being second in line, you can watch and learn. But his extra height, arm strength, and experience provide more options than those available to me.

This is the crux pitch of 21 metres (70 feet). It’s clear there is no other way than straight up. My breathing is heavy, and chest is tight as I begin. Each finger hold seems desperate, and I can’t believe that the rubber edge of my Volleys (tennis shoes) can stick on such small, jutting out pebbles. I’m panting, as much from panic as from exertion. My eyes desperately search for another hold, so I can move up. Each move is into uncertainty, but I have to keep up the momentum. I can’t freeze on this wall – there is no possibility of retreat.

On the top of pitch 8, exhausted and emotionally depleted, I heave myself onto the ledge, assisted by the reprieve provided by a tight top rope. It feels like I am exhaling for the first time. Warwick sets up for the next, final pitch.

As he disappears from view, I’m alone on a thin, sandy ledge, watching skinks leave footprints, simply listening and alert to feeding rope as I belay. I watch as Narrowneck, the long cliff-lined plateau on the far side of the valley, casts a shadow across the valley floor as the sun starts to drop towards it. A lyre bird’s chatter reaches me as it scratches in a shaded gully far below. There is just thin air and a sizeable and sobering drop beneath me.

The last pitch is tricky. Once clear of the exposed face, the only way up is through twenty-one metres (70 feet) of chimney - two walls with a narrow gap between, pushing with my back against one wall and my knees, feet and hands pushing against the other, inching upwards, looking for any advantage, a jut, crack, or hold to gain purchase. Every move is an effort. Looking down, I know that only opposing pressure against the two walls keeps me from falling and being jerked to a halt by the top-rope. I also know that getting back into the chimney position from here would be a challenging manoeuvre after a fall. The mantra of "don't fall" plays repeat in my head. The rocks bite into my hands, as I clench on harder in reflex.

The rear of the chimney continues to narrow. It now feels as though I will be trapped in this slot like the Aboriginal sisters of legend. The walls close in, and the smell of lichen and cold air amplifies the feeling of constriction. To escape my imprisonment, I am forced to move out closer to the very edge, which at this point overhangs the valley without interruption. It is terrifying and my legs are trembling. I understand exposure for the first time.

Then the gap widens and there is more room to shift and change positions; I can now bridge the gap with one foot on either wall. As I emerge from the crevasse, a hand reaches out to me. I grab hold and feel like the fingers of the sisters themselves are reaching out to me, willing me to keep on moving up.

Scrabbling up the last of the slope, I stand exultant in pure air, deliriously happy to have escaped my possible entombment, and with the whole valley spread below. We’ve climbed so high that beneath me are the two wedgies, circling and drifting far below.

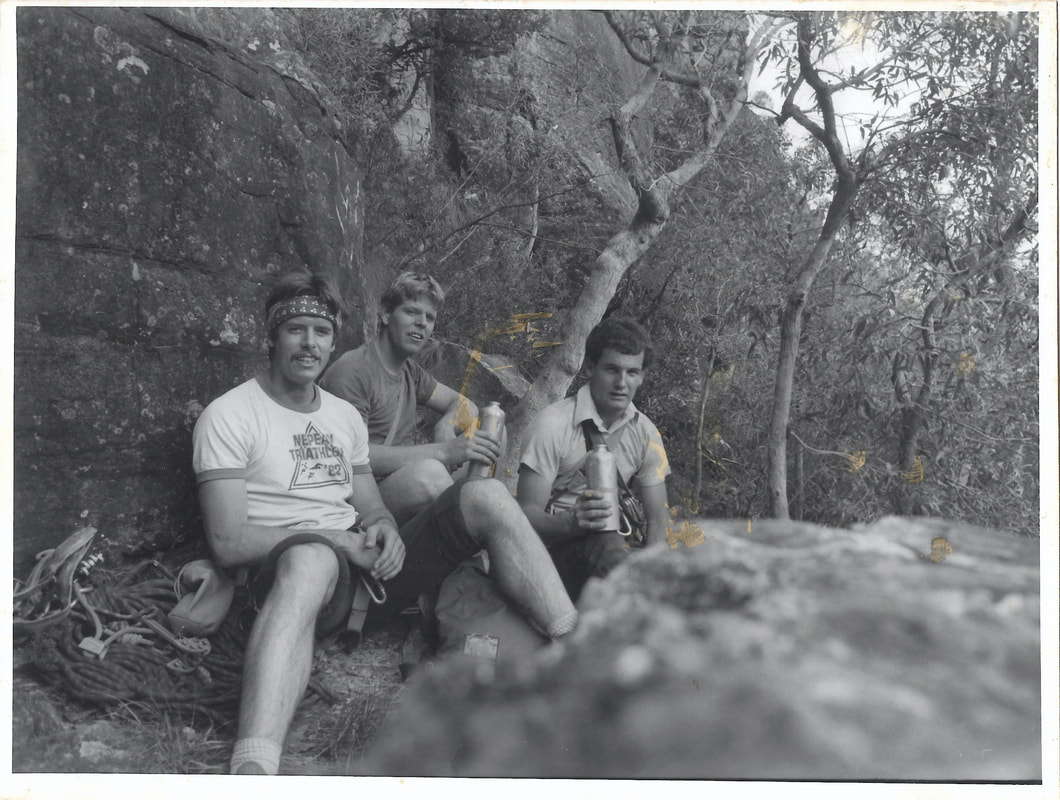

The sunset glows over our tired and dirty bodies. We wind our ropes, check gear and get back to a rock overhang camp as quickly as possible before dark sets in.

Scrabbling up the last of the slope, I stand exultant in pure air, deliriously happy to have escaped my possible entombment, and with the whole valley spread below. We’ve climbed so high that beneath me are the two wedgies, circling and drifting far below.

The sunset glows over our tired and dirty bodies. We wind our ropes, check gear and get back to a rock overhang camp as quickly as possible before dark sets in.

A fantastic great day’s climbing and one of the best routes in the country.

-- Simon Carter - Blue Mountains Climbing – 2010 Ed., Page 47

EPILOGUE

Behind this story is another, about the enduring bonds of camaraderie extending over more than 50 years through my membership of the Sydney Rock Climbing Club - how the smell of the sandstone and campfire smoke from those early days are now fused into our skin and hair and memories and the love of rock has absorbed into our blood. The risk and achievement of climbing were not just heady but nurturing and sustaining. It’s where we learnt to overcome difficulty and discomfort and push beyond our limits to achieve ever harder climbs. It was a training ground of character, of trust and it built resilience.

My thanks to the many members of the Sydney Rock Climbing Club (SRC) who provided material and assisted me in the writing of this story, especially to Keith Bell, for his encouragement and skilled editorial support, to P’Tortise (Ian Paterson) for his superb cliff and valley photos, and to Lee Smith for developing and activating the former SRC ‘Rockies’ email group and for encouraging us to contribute.

There is also some important history to this climb and the Three Sisters. In 1951, the first ascent of The West Wall by Russ Kippax and Dave Rostrum ushered in a 55-year period, where this popular climb provided many climbers, including myself, their first experience of the thrills (and terror) of multi-pitch climbing. Unfortunately, in the end, its popularity, along with its historic antecedents, eventually combined to prohibit its enjoyment by climbers – forever.

In 2006, climbing on the Three Sisters massif was banned by the local Blue Mountains (Katoomba) Council, apparently due to the unchecked erosion of sparse vegetation and the safety risk of falling rocks. Both these hazards accelerated when two new local climbing and adventure businesses started, causing increased climbing activity around Katoomba’s cliffs, of which the West Wall was a popular destination.

In the story I refer to the Aboriginal legend of the Three Sisters. It was not until 2014 that Aboriginal reverence for this outstanding landform was fully recognised, with The Three Sisters site officially declared a protected "Aboriginal Place" by the then Minister for Heritage and for the Environment, Robyn Parker. The area is highly valued by the neighbouring Aboriginal peoples of the Gundangurra, Wiradjuri, Tharawal and Darug nations for its majestic land formations, incredible views across the ranges and down into the valley to the Kedumba River cleaving its way through the Jamieson Valley past the imposing Mt Solitary.

Behind this story is another, about the enduring bonds of camaraderie extending over more than 50 years through my membership of the Sydney Rock Climbing Club - how the smell of the sandstone and campfire smoke from those early days are now fused into our skin and hair and memories and the love of rock has absorbed into our blood. The risk and achievement of climbing were not just heady but nurturing and sustaining. It’s where we learnt to overcome difficulty and discomfort and push beyond our limits to achieve ever harder climbs. It was a training ground of character, of trust and it built resilience.

My thanks to the many members of the Sydney Rock Climbing Club (SRC) who provided material and assisted me in the writing of this story, especially to Keith Bell, for his encouragement and skilled editorial support, to P’Tortise (Ian Paterson) for his superb cliff and valley photos, and to Lee Smith for developing and activating the former SRC ‘Rockies’ email group and for encouraging us to contribute.

There is also some important history to this climb and the Three Sisters. In 1951, the first ascent of The West Wall by Russ Kippax and Dave Rostrum ushered in a 55-year period, where this popular climb provided many climbers, including myself, their first experience of the thrills (and terror) of multi-pitch climbing. Unfortunately, in the end, its popularity, along with its historic antecedents, eventually combined to prohibit its enjoyment by climbers – forever.

In 2006, climbing on the Three Sisters massif was banned by the local Blue Mountains (Katoomba) Council, apparently due to the unchecked erosion of sparse vegetation and the safety risk of falling rocks. Both these hazards accelerated when two new local climbing and adventure businesses started, causing increased climbing activity around Katoomba’s cliffs, of which the West Wall was a popular destination.

In the story I refer to the Aboriginal legend of the Three Sisters. It was not until 2014 that Aboriginal reverence for this outstanding landform was fully recognised, with The Three Sisters site officially declared a protected "Aboriginal Place" by the then Minister for Heritage and for the Environment, Robyn Parker. The area is highly valued by the neighbouring Aboriginal peoples of the Gundangurra, Wiradjuri, Tharawal and Darug nations for its majestic land formations, incredible views across the ranges and down into the valley to the Kedumba River cleaving its way through the Jamieson Valley past the imposing Mt Solitary.