|

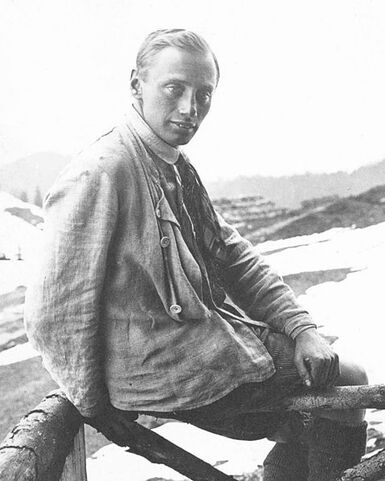

If you aren’t a student of climbing history, you might be forgiven for believing that big wall free soloing was invented by Alex Honnold, unaware that more than one hundred years ago, soloing difficult rock walls thousands of feet high was not an uncommon practice, and that one climber, a young Austrian named Paul Preuss, had so perfected the art that one of his contemporaries, the great Tita Piaz, the Italian climber himself known as the “Devil of the Dolomites” for his own audacious climbs, called him “Lord of the Abyss.”

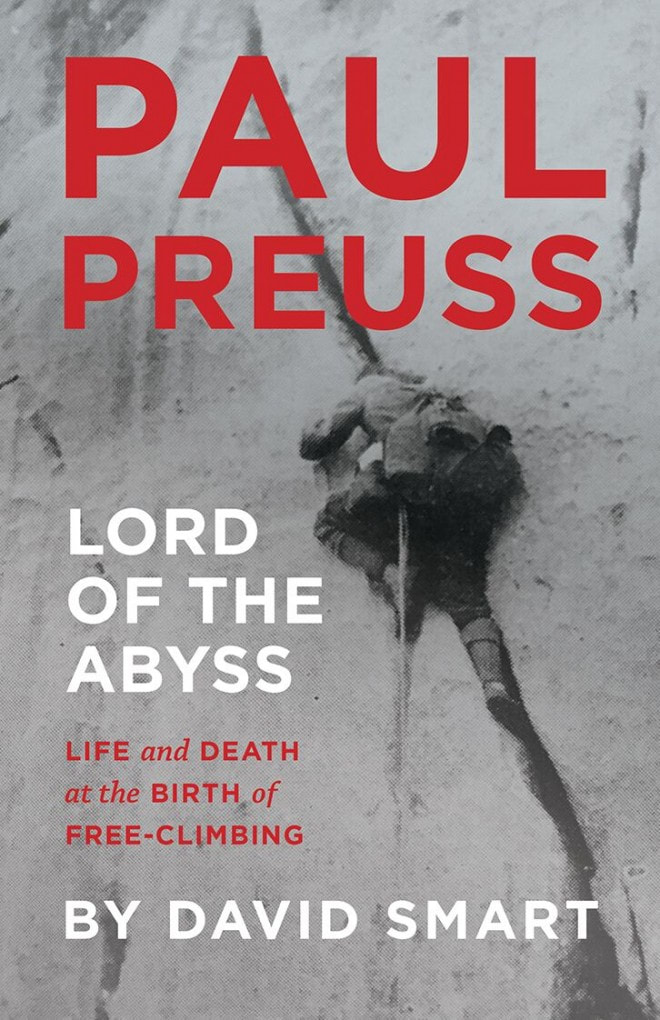

“Paul who?” you may ask. You would not be alone. As David Smart writes in the introduction to his book, Paul Preuss: Lord of the Abyss, many modern climbers have never heard of Preuss, and most who have don’t know how to pronounce his name correctly. (It rhymes with Royce.) Although I had read about Preuss while researching for a writing project, information about him was sparse. It’s not that there’s no literature about Preuss; there’s plenty—what remain of his diaries, articles by and about him, even two books written by Reinhold Messner—but it’s mostly in German, buried in archives in Austria and Italy. Smart, the editorial director of Gripped Publishing, founding editor of Gripped magazine, and author of five guidebooks, two novels, and a memoir, A Youth Wasted Climbing (and winner of the Banff Centre Mountain Film and Book Festival 2019 Summit of Excellence Award, I might add), picked Preuss as a subject because of his relative obscurity. “[Preuss was] the single least well-known figure of importance in rock climbing history whom I could find,” Smart told me. “In Canada, where much of climbing culture was brought by Germans and Austrians, he was discussed occasionally, but mostly as a sort of positive but two-dimensional figure. I wanted to find out what he was like, and the more I found out, the more important he seemed to become, not just as a climber, but also as a philosopher.” |

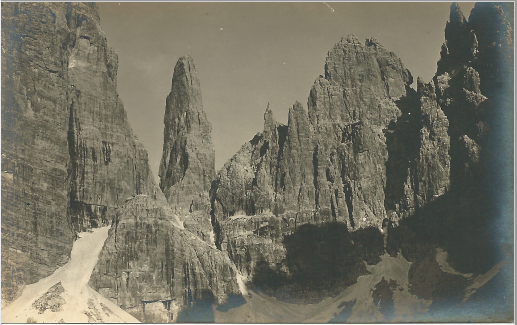

Lord of the Abyss reveals Preuss as a complex individual driven by an innate need to climb, who overcame a childhood illness that rendered him unable to walk and snuck off to do his first technical climb at age 12. Such exploits continued into Preuss’s adulthood; if a difficult route up a peak captured his attention, he climbed it, often alone. During his lifetime, Preuss made many important first ascents, most of them solo, of some of the most-difficult rock climbs in the Alps. One, his solo first ascent of the East Face of the Campanile Basso, a 300-meter-high limestone tower in the Brenta Dolomites, in 1911, stands out in Smart’s mind as being an outrageous thing to solo, due to the commitment, exposure, routefinding challenges, and the nature of virgin limestone which tends to be dangerously loose. “Doing it in rope-soled shoes alone when you knew it was likely the hardest thing anyone had yet climbed makes it seem pretty out there,” says Smart, who climbed the East Face and other Preuss routes while researching his book. “It is very exposed, right from the start, and there was no real possibility of rescue.”

Smart’s book, which was shortlisted for both the Banff and Boardman Tasker awards in 2019, delves deeply into Preuss’ philosophies of climbing. Although Preuss believed soloing was safer and more morally defensible than roped climbing—because in that era a leader fall would often result in a broken rope or an entire climbing team being yanked off the mountain—something Preuss had personally witnessed—he was driven to prove that technically difficult climbs chould be done without pitons or ropes, a statement that Smart acknowledges “required accepting the possibility of death.” Although the advent of pitons and carabiners had made roped climbing safer, Preuss rejected them as unnecessary, believing a climber’s safety depended on his skill and control, not in reliance on equipment. His writings on the subject sparked the Mauerhakenstreit or “piton dispute,” a debate between Preuss and other leading climbers of the day that is reminiscent of the bolt wars that erupted in the 1980s. Preuss published a list of “rules” or “theorems” (which Smart translated for his book) that advocated for a pure style of climbing.

Preuss steadfastly adhered to his numerous rules, nearly always foregoing the use of pitons and downclimbing instead of rappelling. His bold first ascents, difficult solo climbs, and compelling articles about climbing and ski mountaineering made him a popular lecturer; his lantern-slide presentations filled theaters and concert halls across eastern Europe. It’s little surprise that Preuss’s unwillingness to compromise his strict ethics and his need to continue to climb bold new routes for his articles and lectures, as well as to prove himself to his critics, was ultimately his undoing. In 1913, Preuss attempted to make the first ascent—alone—of the North Ridge of the Mandlkogel, and fell 300 meters to his death.

Smart extensively researched his book, traveling to and climbing in the Austrian Alps and Dolomites, making his own translations of letters, articles, and books by and about Preuss, and visiting libraries, archives, and the Messner Mountain Museum at Corones, Italy, where Preuss’s piton hammer is part of the permanent display. Smart acknowledges the irony that Messner’s museum is built around Preuss’s piton hammer, considering Preuss placed two pitons in his entire climbing career (Messner has one of them, the other is still in-situ on a wall), but if not his piton hammer, what? A free soloist of Preuss’s generation could leave little behind except his legacy, and like Messner’s museums, Smart’s book has helped preserve that legacy. Lord of the Abyss is not only a scholarly biography of Preuss and history of early rock climbing in the Dolomites, but an engaging story illuminating in words and photos the life and death of one of the most compelling, nearly forgotten heroes of early free climbing. It reminds us that for all that climbing has changed in the past century, it really hasn’t changed very much at all.

As much as I enjoyed Lord of the Abyss, I’m looking forward to reading Smart’s upcoming book about Italian climber Emilio Comici, who is credited with inventing big-wall climbing and taking up Preuss’s free-soloing mission. In 1937, Comici soloed the North Face of the Cima Grande (a route he had pioneered in 1933) which was regarded as the greatest solo climb yet done. George Mallory said that “no one will ever equal Preuss,” and yet Comici in some respects exceeded him, if not ethically, at least technically. “I see the books as complementary glimpses into the two paths in climbing that actually often overlap in wonderfully creative ways: the tool users and the purists,” Smart told me. If his book about Paul Preuss is any indication, Smart’s book about Comici will be equally well researched, engaging, and important to preserving the legacy of another of climbing’s most compelling historical figures.

PAUL PREUSS: LORD OF THE ABYSS

David Smart. Rocky Mountain Books Ltd. 2019

Rocky Mountain Books (RMB)

ISBN 9781771603232

247 pages. $32.00 CAD

Smart extensively researched his book, traveling to and climbing in the Austrian Alps and Dolomites, making his own translations of letters, articles, and books by and about Preuss, and visiting libraries, archives, and the Messner Mountain Museum at Corones, Italy, where Preuss’s piton hammer is part of the permanent display. Smart acknowledges the irony that Messner’s museum is built around Preuss’s piton hammer, considering Preuss placed two pitons in his entire climbing career (Messner has one of them, the other is still in-situ on a wall), but if not his piton hammer, what? A free soloist of Preuss’s generation could leave little behind except his legacy, and like Messner’s museums, Smart’s book has helped preserve that legacy. Lord of the Abyss is not only a scholarly biography of Preuss and history of early rock climbing in the Dolomites, but an engaging story illuminating in words and photos the life and death of one of the most compelling, nearly forgotten heroes of early free climbing. It reminds us that for all that climbing has changed in the past century, it really hasn’t changed very much at all.

As much as I enjoyed Lord of the Abyss, I’m looking forward to reading Smart’s upcoming book about Italian climber Emilio Comici, who is credited with inventing big-wall climbing and taking up Preuss’s free-soloing mission. In 1937, Comici soloed the North Face of the Cima Grande (a route he had pioneered in 1933) which was regarded as the greatest solo climb yet done. George Mallory said that “no one will ever equal Preuss,” and yet Comici in some respects exceeded him, if not ethically, at least technically. “I see the books as complementary glimpses into the two paths in climbing that actually often overlap in wonderfully creative ways: the tool users and the purists,” Smart told me. If his book about Paul Preuss is any indication, Smart’s book about Comici will be equally well researched, engaging, and important to preserving the legacy of another of climbing’s most compelling historical figures.

PAUL PREUSS: LORD OF THE ABYSS

David Smart. Rocky Mountain Books Ltd. 2019

Rocky Mountain Books (RMB)

ISBN 9781771603232

247 pages. $32.00 CAD